How a Sacramento man kept 8 ‘spiritual wives’ and 21 children hidden, and no one intervened | Opinion

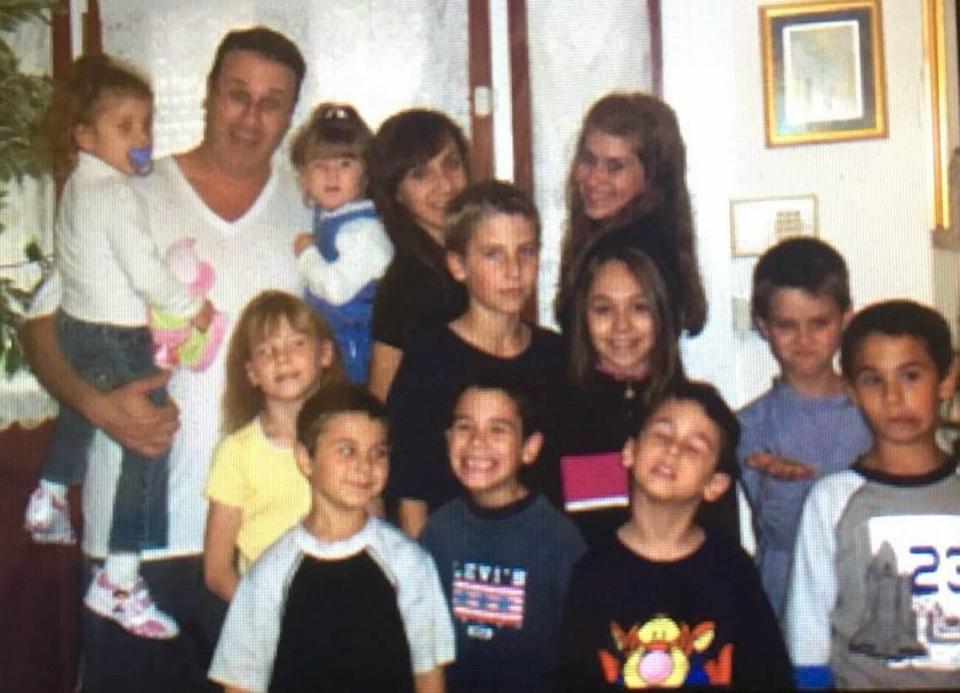

Most of the eight women who had a total of 21 children with Norman Masters were kids themselves — “young and from troubled households,” when they moved in with him, said Sheri Sepanski, who was the first to do so. She was 16 at the time, and distraught one night after overhearing her alcoholic mother make some hurtful comments. “He said, ‘You shouldn’t have someone like that in your life. Get a bag, and I’ll get you away for a couple days,’ which turned into 27 years.”

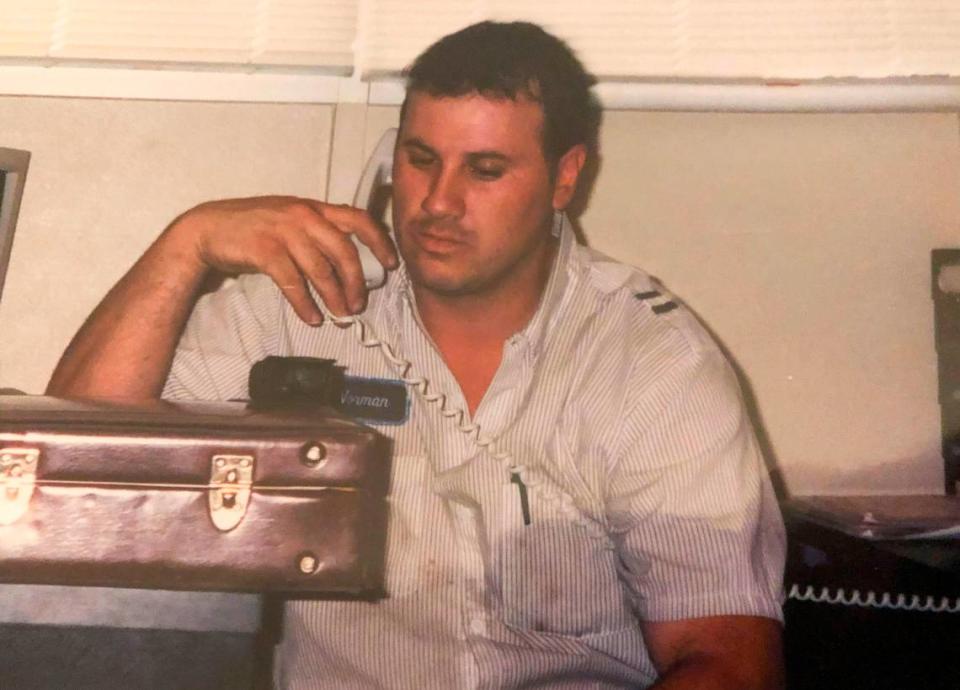

Norm was only a year older than Sheri, but was already bouncing around on his own in Sacramento in the mid-80s, making a living selling bootleg cologne and cassette tapes at flea markets. Even then, he did not lack either confidence or the authority that he insisted came from God. Less than a year after Sheri moved in with him in 1988, she told me, he announced that the Almighty had come to him in a dream and told him he should also have “spiritual children” with other “spiritual wives.”

When that’s what happened, he and seven of the eight women and their children with him all lived together right here in Sacramento, in various combinations, under rules that were strict but constantly changing, and that never applied to Norm at all, in what Sheri now sees as a cult. When one of the women managed to escape, “he told us she had died of leukemia.”

Opinion

In separate interviews, three of these women and five of their children all said that Norman Masters had starved, isolated, beaten and terrorized them for years, yet has never been brought to account, other than in a Sacramento family court hearing on a protective order that found him responsible for inflicting “a lifetime of abuse.”

One of his daughters, Megan Masters, said that at age 5, after being forced to work alongside the others tearing down a shed all day without food or water, she got so thirsty that she chugged the bleach he kept in a Mountain Dew bottle. Then, she said, he refused to get her any medical care while she screamed in pain. Another daughter, Bonita Simon, told me that when she was 8 or 9, he started taking her along to the weekly auctions where he bought junk cars — and where he’d leave her alone with strange men while he negotiated. And sometimes, Bonita said, those men did things that she didn’t understand.

Today, Norman Masters lives with one grown son and the one woman who still hasn’t left him at the sprawling, highly fortified used car lot in Del Paso Heights that he’s run all these years, and keeps in his one remaining partner’s name. The only sign of life there on a weekday afternoon was the German shepherd that came bounding out to the chained front gate.

He refused to speak to me, either in person or on the phone. “You just write your story, believe what you want to believe and we’ll go from there,” he said in a text.

But in a series of other text messages, Masters called all allegations against him “nonsense,” said a “relationship doesn’t survive 37 years because it’s abusive” and described his children as spoiled. “I’m not going to dignify 37 years of my life to the public, let alone to a couple of kids who are upset” and have “daddy issues” because their parents aren’t together any more.

So why would these women invent such a horror story? “Have you ever heard of a positive separation?” Masters texted. “I guess when the gravy train stops, they get angry.”

And your children? “Nobody locked anyone up, nobody (beat) anyone so I’m not quite sure what you’re talking about,” he wrote. “Nobody ever molested anyone and I find it hard to believe that any of my kids would say something like that.”

They did, though, and do, in horrifying detail. The same Sacramento family court that granted Sheri Sepanski and her minor children a rare five-year protective order in 2017 said it believed her and everyone else who testified against Norman Masters. “The court did not find Mr. Masters’ testimony to be credible,” the decision said.

What he calls “the gravy train” looked like this to those who just wanted it to stop so they could get off: Though there was always food in the house, they said, only Norm could eat his fill, while the children tried not to cry from hunger and the women tried to keep them still to avoid setting him off.

Later, when the kids were old enough to work, his children and their mothers said, they had to turn all of their earnings over to him, sometimes in exchange for the “Masters money” he’d had printed with his face on it, which on special occasions they could use to buy snacks from him.

Masters’ control was so absolute, they said, that his children and their mothers at times needed his permission to use the bathroom. The women were taught to inform on one another, and to confess their own supposed sins each evening when he came home. Under his made-up rules, looking at male animals was considered immoral for women, as was looking at any male child who was not one’s own son. Some of the children never attended school, and for years, none was allowed to go outside.

Masters never legally married any of the women, and taught them to live in fear, of the world in general and of police in particular.

Though Masters’ parents were devout members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, religion “was only a cover for him,” said his eldest son, Josh Sepanski, who is 27. “I don’t think he even believes in God.” In Norman Masters’ house, he himself filled that role. But while his beliefs are his own business, his actions are not.

Court finds physical abuse, neglect and financial abuse

Court records show that Norman James Masters, who is 54, was convicted for receiving known stolen property in 1989, for battery in 1990, petty theft in 1996 and receiving stolen property again in 2008.

In 2007, according to court records, he was arrested for “cruelty to a child” and “inflicting corporal injury to a spouse/cohabitant.” The woman who called the police that night, after she said he choked her and pushed her down in front of their daughter, told me that no charges were ever filed.

It was that same year that he was also arrested for receiving stolen property and running a chop shop on the car lot he still operates. And those charges landed him in jail for four months in 2008, which says something about how kids and “cohabitants” rate vis-à-vis car parts.

In 2018, he was charged with eight counts of fraud — insurance, welfare, social security and tax fraud. But “he comes into court and says he has cancer,” said Sheri, “and comes into court and says he was run over,” so the case just keeps getting continued. Which happened again on March 8 of this year, this time because his defense attorney either was fired or withdrew.

Yet according to his family and two Sacramento court rulings, Norman Masters’ alleged financial misdeeds are not his most serious crimes. And once again, I have to ask why we take violence against women and children so lightly, and then are surprised that this lack of serious consequences reliably leads to more of the same.

In the custody case between Sheri Sepanski and Norman Masters, the 2017 decision awarding her full custody and denying him visitation ordered him to “complete a batterer’s treatment plan.”

In a separate ruling on a 2017 domestic violence case in Sacramento County, “the court finds that on April 4, 2017, Mr. Masters did threaten to kill Mr. Joshua Sepanski and his mother Ms. Sheri Sepanski. … The court further finds … that Mr. Joshua Sepanski suffered a lifetime of abuse at the hands of Mr. Masters. This included physical abuse, neglect (not allowed out of home until 9), and financial abuse of taking his earnings while a minor.

“The court found compelling that after one of the mothers of Mr. Sepanski’s half-siblings had left Mr. Masters that Mr. Masters found Joshua to chastise and threaten him with harm. Due to this lifetime of abuse, which consisted of extreme forms of control and manipulation, along with threats that were then carried out, the court finds it reasonable” that Sheri and Josh Sepanski took these threats seriously.

“All Petitioners’ witnesses credibly testified to the choking of Ms. Sepanski after she came to stop Mr. Masters from beating Isaac Sepanski.”

The court granted the protective order to Sheri Sepanski and her minor children, and noted that Bonita Simon had “credibly testified” that she had not called the police on her father sooner because he “had informed her that if she ever did he would kill her, put her in a tree shredder, feed her to the pigs and no one would ever find her.”

Masters said that if any of this were true, he would not still have shared custody of one child, which he does have, and visitation rights to another, which he did have until she turned 18 not long ago. If any of this were true, he said, he would not have a grown son still living with him. And yes, his son did move back in with him after a stay in juvenile hall, because his mother said he couldn’t keep using drugs and live with her. Only, the fact that some of Masters’ kids are struggling is not exactly exculpatory.

After his partner’s murder, police came knocking

So why has this man still not been held accountable for any of the allegations characterized as credible by the court?

Sheri and Josh Sepanski said a police fraud investigator, who declined to talk to me, told them that any violence against them would be outside the statute of limitations now. But under California law, survivors of physical, mental or sexual child abuse can actually come forward until they’re 40.

And it isn’t as though local law enforcement never heard of Norman Masters: The mother of a child of his who never lived with the others, and got out after only two years, told me that Sacramento cold case detectives visited her in 2008, four years after Norm’s best friend and business partner, former bail bondsman Manuel Alexander, was kidnapped from his home in the Pocket neighborhood and shot to death in October of 2004.

The night Alexander was killed, Masters’ son Josh Sepanski said, the FBI came to their house looking for his father, but he wasn’t home. Masters’ daughter Bethany Simon Perry, who lives in Utah with her husband and two children, said “some people who knew Manuel” soon came knocking in the middle of the night, too, though again he was not there. When he did return, he made his whole family sneak out a side door and stay elsewhere for a while.

All these years, not only some of his family members but Alexander’s 79-year-old mother, Buffy Alexander, too, thought maybe Masters did have something to do with her son’s death, because phone records show that he was last to talk to him. Masters, Buffy Alexander said, was “always doing something that was shoddy or not good.”

But Jeff Alexander, who was extremely close to his brother Manuel, said that’s not what happened, and his explanation does make sense: “Manuel and Norm were both con men, basically, in it for the game,” and constantly competing to see “who has the biggest scam.” His brother was killed in retribution for one of those scams, Alexander said, and “the only reason they didn’t get Norm is he didn’t answer the door.” When they came for him, that was just one more time, and one more way, he’d put his children and their mothers in danger.

Masters told me the police know he didn’t do it, and what’s more know who did. In an email, a spokesman for the Sacramento Police Department said, “I spoke with our homicide team who advised this case is still an open and active investigation.”

Masters was so afraid he’d be next, Jeff Alexander said, “that I’m surprised he didn’t shut his car lot he’s never sold a car out of. Norm, he’s still running scared, because he’s cheated so many people.” His own family most of all.

‘I was 19. I didn’t know what red flags were’

Not long after her graduation from Golden Sierra High School in El Dorado County in 1991, Christa Simon met 22-year-old Norman Masters at the Denios Farmer’s Market in Roseville, where he was selling his bootleg cassette tapes. They exchanged phone numbers, and on their first date, went to Reno. “That night, he bought me a beer, even though I was underage, and then later on criticized me” for drinking it.

That’s how their whole 24-year relationship went, she said, but “I was 19. I didn’t know what red flags were.” She did know what physical abuse was, and is hard on herself now for covering for him instead of bolting when “he slammed me up against a waterbed frame” and caused huge bruises. “Another time, he was yelling at me and had this round brush he did his hair with and was whacking me on the head with it, and I had four huge lumps on my head. Why didn’t I realize I needed to go?”

Why? Simon supplied the answer to her own question, which is that he took a vulnerable girl and made her steadily more so, in part by starving her, both literally and emotionally, so that before long “I’ve lost all this weight because you’re not feeding us. I weighed 98 pounds.”

Only gradually did she come to understand why three other women, including Masters’ “ex-girlfriend” Sheri Sepanski and someone he’d gotten pregnant the summer before her freshman year in high school were always around: because they were all still together.

“They seemed really nice, and then they started staying with us” and eventually “started taking turns sleeping in what was once my bedroom. I remember being sad all the time, and I’m sleeping on the living room floor” and being “dragged up the stairs by my hair.”

Yet Masters, she said, constantly repeated that he had been sent to save her and the others from their sinfulness and bring them all to the highest level of heaven. “He was, ‘God this’ and ‘God that.’”

Simon had five children with Masters, and they, too, were kept hidden from the world, behind windows that he painted white. “He taught me to not really speak much.”

Leaving took years and a lot of courage

After her daughter Bonita Simon grew up and got out at age 19, with the help of her employer at a thrift shop run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Bonita Simon did call the cops on her father.

When they showed up, Christa Simon was too afraid to tell them there was a problem, but they gave her a card that they said she should hang onto in case she ever changed her mind. That business card felt like both a lifeline and a potential source of trouble, because what if Masters found it? In a panic, she burned the thing.

Leaving him took years and a lot of courage, but Christa’s mental breaking-away point came in 2014, when “I was staying in a motor home on his car lot with my boys and had to ask if I could wash my clothing, and he told me no.”

None of the women was allowed to have a job, but after that, Christa saved a total of about $250 from recycling cans. Through Bonita, she got help from an uncle she hadn’t seen in decades and from her father, who had work lined up for her at a Harrah’s in Nevada.

She had one friend, a woman from the neighborhood, and that connection gave her a little extra strength, as did Norm’s absurd admonition that Bonita couldn’t bring her newborn over, because she’d had a little boy, and if he visited, Christa might see her grandchild’s baby penis and be sullied by the sight. Sheri paid to put Christa’s belongings in storage, and the minute Christa turned off her phone and hit the road for Nevada, “it felt amazing.”

Only after she’d moved into a women’s shelter in Carson City, in June of 2015, did she learn that her parents had been looking for her for many years, and had “concluded at one point that I was dead.”

Their reunion felt like a miracle, and her mother’s prayer that she’d see her girl again before she died was answered. Not all of Christa’s family relationships have been fully repaired, though, as much as she’d like them to be. And at first especially, “I didn’t know how to act because I’d been kept out of society so much.”

Not surprisingly, she does not say that the damage done to her and to her children is all behind them now. “Some days I hate myself for being there as long as I was, because the kids are messed up from not being fed enough.”

She still hears Norm’s voice in her head, too. “Some days I’ll sit and think about things he said — you’d never make it in the world, and no one else would ever want you. I left him eight years ago and I am still single” so was he right, she asks herself.

“I have a good circle” of friends who assure her that’s not the case, “but that’s in me” even if life is so much better now that she’ll never stop appreciating freedoms most of us don’t even think about. “I can wash my laundry whenever I want to,” she said, and thanks to her job at a DMV, “I can go to the grocery and buy whatever I want.” She’s no longer sad all the time.

‘How amazing would it be if he got arrested, and I got to do it?’

At 29, Bonita Simon is married with two young kids, who are 7 and 2, and a third who is her 7-year-old stepdaughter. She works in a prison in Nevada, and some of the things she sees there give her flashbacks of home: “I’ll watch an officer take down a guy, and it puts me in a ‘fight or flight’ situation.”

She was recently accepted to a police academy, where she’ll begin in July, and loves the idea that going into law enforcement will be “the biggest f--- you” to her lawless father: “How amazing would it be if one day he got arrested, and I got to do it?”

Everyone has knowledge and cultural gaps — shows we didn’t watch, books we didn’t read — but Bonita never went to school a day in her life until she was 19 and studying for her GED.

Once, after he started letting them attend church when she was about 10, everyone in her Sunday school class was invited to relate a favorite childhood memory, and “I didn’t have one, so I made something up,” and whatever she said was so wobbly and obviously fabricated that the other kids laughed.

Bonita’s oldest real memory dates to when she was about 6 and living in a house with four bedrooms. A mom and her kids lived in each one, plus a fifth woman stayed in the living room and a sixth occupied the garage, where there was no insulation or indoor plumbing.

One day, Bonita said, when Norm had invited the woman who lived in the garage into the house to have sex in the living room, all of the other women and children were supposed to stay in their rooms and be quiet. Only, Bonita had to go to the bathroom, and finally got her mom to agree that she could go if she just dashed there and back, looking at nothing as she did so.

Of course she did look, though, and when her father saw her seeing him, he beat Bonita’s mother, who had been nursing her newborn at the time. “I ran over and picked up the baby, and he kept hitting her.”

Another dominant memory, not only for Bonita, is that “I would go days without eating. We had food, but only he could eat it, and we weren’t allowed to tell him we were hungry.” As a result, “sometimes I even have a hard time not resenting my mom. As a mom myself, to watch your kids be hungry?” But then again, she recalls one occasion when her mother did beg to get the kids something to eat, and Masters responded by throwing cans of food at her.

Years of abuse followed by nightmares and counseling

At 8 or 9, Bonita’s father started allowing her to go outside “when it benefited him.” She and a sister would go with Norm to car auctions where while he went off and negotiated, they were left with men they didn’t know, “and we’d get one bag of Cheetos to share in exchange for not telling our moms” they’d been left alone.

Some of these ad hoc babysitters, Bonita said, would “touch us and do really creepy things.” Bonita’s mother, Christa Simon, said she did not hear about this at the time, but has been told about these experiences many times in the years since they “escaped.”

“Sometimes,” Bonita said, “I’m surprised I’m not more f---ed up.” And that her father isn’t locked up, though she and the others still suffer from his past behavior: “A few siblings act just like him, and one is strung out on drugs. We’re coping in different ways.”

At 13, Bonita finally asked her mother why they couldn’t just leave, and when her mom “confessed” to Norm that Bonita had said that, he shoved Christa’s head into the wall. “Never say that again,” Christa told her daughter.

Which isn’t to say that Norm’s thinking didn’t influence Bonita. “I thought he was crazy, but sometimes I’d believe what he’d say, like he’d say we’d go to hell if we didn’t” agree to polygamy and “marry someone with multiple wives.” When she was 17 and dating a boy from their church, “I said I couldn’t marry him unless he agreed to have multiple wives. That scared him off.”

One day, in her first job in the thrift store, she heard some coworkers talking about something called the Holocaust. She could tell from context that this something was horrible, and after the others had gone, asked her manager what that word meant.

Was she so starved for attention, he asked, that she was really pretending not to know? But when he saw that she was serious, he explained the history. And then, though he didn’t know the half of it, or even the tenth, he helped her leave the father she’d only described to him as abusive. That’s really all she’d told him, but that was enough. She could move in with another coworker who had an extra bedroom, he said, and that’s what she did.

I just want to say here that nearly all of those who helped these women and their children escape their situation were real members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and that the man they left only pretended to be that.

The scariest night of Bonita’s life, she said, was not the night she made a run for it but the night she picked up her mother, three brothers and sister at 2 a.m., with him just down the street, and took them to a Motel 6. She’d had a child of her own by then, and kept thinking, “what if he shows up and hurts my baby?”

She has nightmares still about her early life, and never talks about it, other than in counseling and to her husband. The few times she’s even started down that road, people either didn’t seem to believe her, or immediately started saying things like, “Yeah, my life was like that, too.” No, it wasn’t.

What a paradox that we live in a world with both too little and, in some ways, too much privacy, with every online move tracked for profit, but concealment of what the court called a “lifetime of abuse” within a family is all too easy.

Women had nowhere to go

Today, Sheri Sepanski is a professional face painter married to a retired city bus driver she met through a Christian networking group. Funny, she said, that her husband’s old route regularly took him past the house where she and the others used to live on Steiner Drive in South Sacramento. “There was a 6-foot fence around the house, with a padlock on the outside. I was behind a padlock.”

Did her husband ever wonder about what went on inside that house as he drove by? No, she said, “because your mind doesn’t go there. Even the mailman didn’t say anything.”

Before she met Masters through a friend from Encina High School, her experience with boys consisted of two dates, to a homecoming dance and to the movies. As soon as he turned 18, she said, “he isolated me” from everyone in her family, including even her younger brother, Harold Rigsby, who told me that when he was 13, Masters hired him and other neighborhood kids to deliver drugs and steal for him.

“Back then, he had charm, looks, money, girls, businesses, so we wanted to be like him. I wanted to see him as the older brother I never had, but he just took advantage” and after arming and putting him and others on the wrong path, Rigsby said, he never even paid them. Rigsby, who went on to kill someone after breaking with Masters, served 26 years in prison and now works in Los Angeles counseling other former inmates.

In 1990, he said, a Sacramento police detective came to ask him about Norman Masters, who she said was under investigation in connection with a crime in Utah, where he’d grown up. Again, he was on the radar of police but again, nothing came of it. “Like everything else, that disappeared” and Rigsby never heard any more about it. When his sister Sheri similarly vanished, he said, no one ever knew why. “We didn’t know he wasn’t allowing her to go out.”

By the time Masters told Sheri Sepanski he’d be taking other wives, “in my mind, I had nowhere else to go,” she said. And “once he had me in submission,” her focus really boiled down to this: “I didn’t want to do anything wrong.”

The family lived in a bunch of different places — a “shack” in Rio Linda, a fancy place in the Cobble Shores gated community, and, until they were evicted, in a house in Natomas that was empty because it was being foreclosed on.

When he went to jail for four months for running a chop shop, Sepanski said, “he was calling every day, and I hated that part of the day. So many people have said that was the perfect time to leave,” but that would have involved talking to the other women about her plans, and “he kept us against each other” and so afraid of being informed on by one of the others that “I didn’t even think of it.” She did, however, teach herself to drive while he was gone, and got her license at age 38.

‘I knew he was playing us at that point’

She checked out mentally the day that Masters told her that one of the other women was not a wife to him, spiritual or otherwise, but was a mere “concubine.” A man who’d say that, she thought, is just making it up as he goes along. “I knew he was playing us at that point.”

She also couldn’t help noticing that she was a lot happier when he was anywhere she was not, and that when she heard his car pull in, “I felt terror.” Still, leaving took seven years. As she pulled away, he even tried being nice, sometimes dropping a little packet of trail mix in front of her, “like it was a dozen roses. Because he was losing control.”

Their health care was always minimal, and she lost all of her lower back teeth because Norm insisted that she only brush her teeth with salt: “He loved sounding knowledgeable, but I think he got it mixed up with baking soda.”

She is not afraid to go public now because she no longer fears Norman Masters. “He’s a coward, and not as powerful as I thought he was.”

When I asked her if there were any happy times, she said they did laugh on the night they met in 1987, when she played an LL Cool J tune on her flute for him. But “he saw sweet little Sheri and thought ‘I can take advantage of her.’ He always left me very confused; that was the pillar of our relationship.” So I’m going to put that down as a no.

Extreme isolation provides cover for violence

How could all of this go unnoticed for so long? So much for “Big Brother is watching you.” And apparently, we are still not our brother’s keeper.

No one ever successfully intruded upon this sprawling family’s unhealthy and extreme isolation, and Bethany, who is 27, is among those who live with the consequences: “I made an attempt on my life and spent some time in a psych ward,” she told me, after she got out and realized the deficits she’d have to overcome. “I had to learn everything from the beginning,” because even the chance to learn how to be in the world “had been taken from me until I was 18 years old.”

Up until then, “I thought everyone lived that way, and it was sh---y and terrifying. I pretty much just hid in corners and closets and lived in my own world because that was the safest.”

One of the standout memories of her childhood, she said, was the time she heard screaming, looked down the stairs and saw Norm kicking one of the mom’s ribs in a fury.

Another, when she was 13, came after he’d broken her older sister’s jaw. She knocked on Norm’s bedroom door and told him “in a very shaky, scared voice,” that the next time he hurt someone she loved, he was the one who wouldn’t survive it. “I got brave that night,” she said.

Come over here and say that, he answered her, and she ran out crying. But not only on that night, the courage and resilience of Norman Masters’ children is every bit as astonishing as their father’s cruelty and weakness.

Masters’ daughter Sarah Sepanski, who is 22, said his legacy in her life is “pretty bad anxiety, trust issues, a lot of things day-to-day.” Loud noises bother her, and crowds bring back uncomfortable memories of being “surrounded by a lot of people in a packed house.”

She tries not to dwell on her childhood, but “looking back, how did people not” demand answers, she asks. At church, she’s sure, “they knew something was off.”

Church members raised questions — but got no answers

One man at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on Havenhurst Drive who did see that something was off was Morgan Reynolds, a teacher and youth minister with a Ph.D. in education.

“A lot of things weren’t adding up,” he told me, about the many children that Norm Masters dropped off for services every week. “We never met any of their mothers,” though he kept trying to, and “it just didn’t feel right.”

The kids were “very skinny” but well behaved, and what seemed the most off was not them but Norm: “I had questions about his honesty” and business dealings, and “didn’t trust anything he said. His statements didn’t add up.” When Reynolds somehow heard that Norm was in jail, he visited him at Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center in 2008, but never got any answers that made sense there, either.

“I felt for the kids,” Reynolds said, and “felt like we needed to take a position, but we could never” clarify the situation. “I’ll be honest; some of the people I was working with were, ‘It’s better not to know.’” Eventually, “there was another church member who said, ‘There’s something going on there,’ and that’s when they moved, and we lost contact.”

Josh Sepanski appreciates that Reynolds was at least trying to look out for them. But he is also understandably angry that the only crimes the authorities seem interested in prosecuting involve the various ways in which Norman Masters is accused of defrauding the government.

“The state doesn’t care about us,” Sepanski said, though much of their story has been aired in family court. “They just want their money back. How is it that they keep stepping aside for this guy?”

With dozens of victims “of this one person, how can there be nothing we can do” about what Josh sees as “the human trafficking of girls from vulnerable situations he held hostage?” Good question.

Shouldn’t CPS have taken multiple reports more seriously?

Child Protective Services was called on Norman Masters at least five times that Christa Simon remembers, including once in 2007 when their son, then 4-year-old Jeromy, who had leukemia, was brought into Sutter Memorial Hospital close to death because medical care had been so long delayed. He survived, after spending many months in the hospital, and nothing came of the medical center’s report to CPS.

In 2008, according to Sheri Sepanski, authorities were alerted after a neighbor noticed her daughter, then 15-month-old Megan Masters, sitting in the gutter in front of the car lot.

They were living at the business at that point, without any running water, but when CPS asked about that, Sheri Sepanski told the investigator, “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” and never heard any more about it: “OK, sorry.” Though it doesn’t have to, CPS always gave the family plenty of notice before visiting.

Court records in the custody case between Sepanski and Masters say, “CPS has received two referrals in 2008 and 2012 alleging general neglect of the children. The dispositions were evaluated out and unfounded.”

Bethany says that whenever “CPS was getting close, he’d move us around.”

Obviously, CPS has a difficult job, one that’s hard to get right and easy to get fatally wrong. But shouldn’t multiple reports have triggered a more serious investigation?

Maybe the law will forever continue to, as Josh Sepanski puts it, “step aside for this guy,” who maintains that his children had nothing but the best growing up, that in speaking up they are looking for attention and money, and that any suggestion of wrongdoing on his part are “statements (that) are done in malice and are very far from the truth.”

He called one daughter with whom I’ve had no contact a drug addict with “a very promiscuous lifestyle” who no doubt said whatever I wanted her to say. Though I know nothing about her situation, that his kids are not all promiscuous drug addicts is the wonder.

The five of his children I have spoken to show no sign that they are acting, as he says, out of anger that their parents are no longer together; on the contrary, that’s the thing for which they’re most grateful.

Josh Sepanski, who was almost 17 on his first day of school ever, at San Juan High School, has a degree from Sacramento State, until recently worked at a software company and has a small videography business. Whether or not the authorities ever bring his father to justice, he hopes to make a documentary that will in some way hold him accountable for, just for instance, coming home to a house of undernourished kids complaining that he had heartburn from overdoing it at the all-you-can-eat buffet.

Also for leaving his children so understimulated that “for entertainment, we’d walk around the couch in circles.” And for the fact that once Josh did get outside, it took years for his eyes to adjust to the light: For the longest time, “the world looked overexposed,” because he was so underexposed.

If he ever does make that movie, it will include this scene: When he was about 6, Masters had finally gotten him the new coloring book he had been begging for. But, oh, he hadn’t checked too carefully what was in the coloring book, so “he comes bursting in saying my mom’s morals have gone out the window because she’s coloring Barney in swim trunks. I used to be frightened because I never knew what he would do next, but now it’s, dude, that’s pathetic. Barney in swim trunks, how do you top that?”

You don’t, and shouldn’t even try.