A Sacramento man spent more than 40 years in prison. Now he’s winning acclaim as an artist

Gary Harrell has known bad days and this was not one of them.

Harrell had gone home after an early-morning shift at his part-time security job to make coffee for his wife and take a nap. He woke to hear her tell him he’d left the hot water on. Now, as he explained, he’d need to get his microwave fixed.

“If it’s not one thing, it’s 10 of another,” Harrell said. “That’s the thing about life on the street. But my worst day out here is better than my best day in there.”

Harrell, 68, was released from San Quentin State Prison in 2020 after serving more than 40 years in different facilities. He had received a life sentence for his role in a 1977 murder. But his story could be far from over, with Harrell, who now lives in south Sacramento, winning acclaim and a recent $20,000 fellowship for artistic work that began inside.

Becoming an artist

Harrell was 21 when his life changed forever and, for a long time, seemingly irreparably.

On March 29, 1977, according to Los Angeles Times reporting the next year, Harrell’s cousin Edward Harrell ordered him and three other men to kill a 33-year-old Santa Ana man named James Harbin. They stabbed Harbin – a pimp who prosecutors said had beaten a female friend of Edward Harrell – 35 times and attempted to kill a woman working for him.

Harrell said he had agreed to give another of the men involved in the attack, George King, a ride that day and that he thought King would just talk with Harbin.

“I used to sell dope,” Harrell said. “And in the course of that, I should have knew something was gonna happen, but I didn’t, because I’m not a murderer. But I had to become a murderer at a pimp’s and I never wanted to be.”

A jury found Harrell guilty of first-degree murder in 1978, and he received a life sentence.

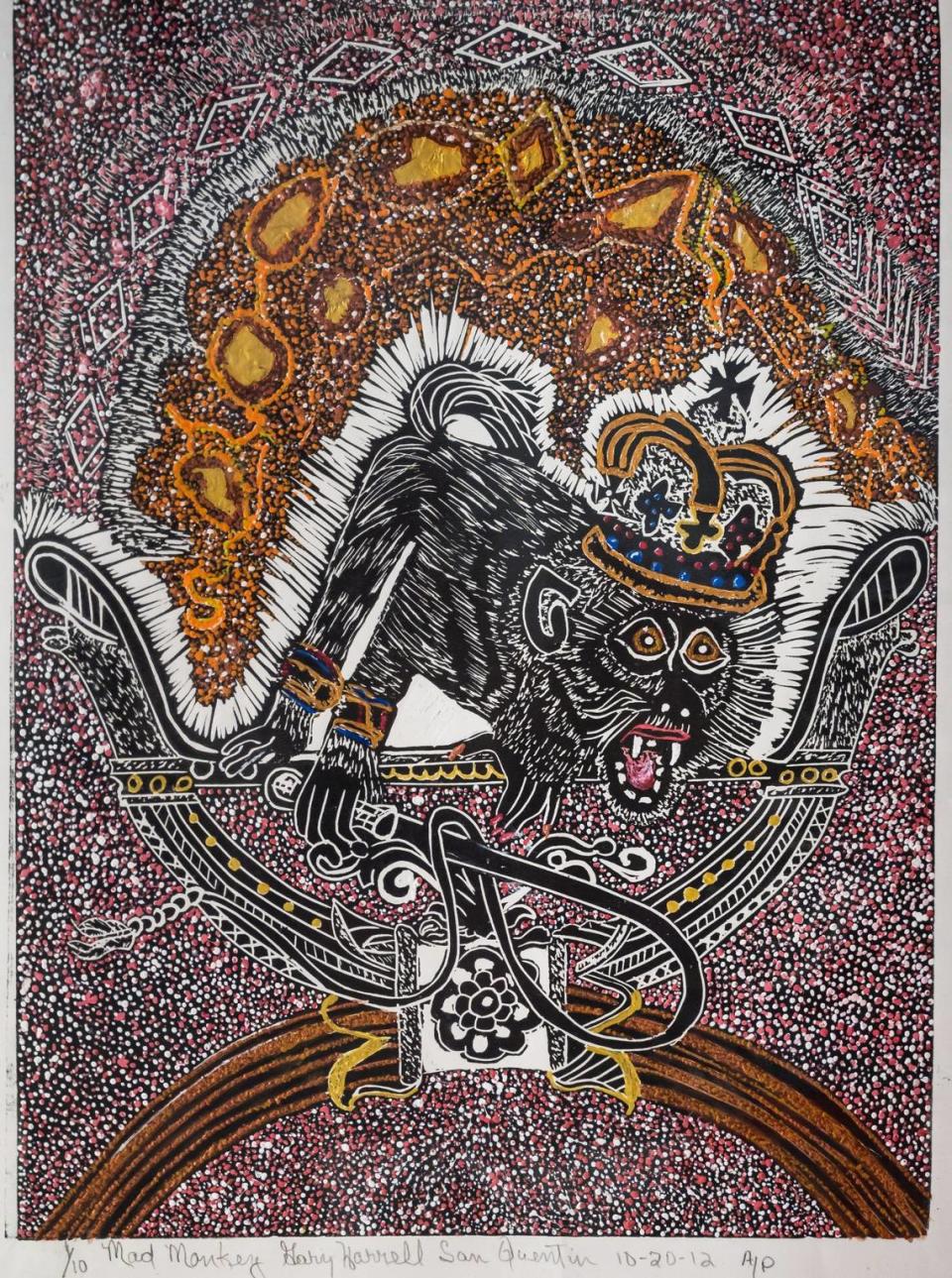

Several years later, Harrell began to make art, initially as a way to have money to purchase commissary items. He began working with leather, then wood, then glass. After being transferred through different facilities, he arrived at San Quentin in 1992 where he would eventually learn block printing.

Benjamin Ballard met Harrell at San Quentin in 1994 when he was serving a second-degree murder sentence and both men were working in the prison’s furniture factory.

“Some people pump themselves up to be a lot tougher than they really might be,” Ballard said. “But Gary never had that kind of persona. He was more down to earth and straightforward and humorous and everything. And I was attracted to that right away.”

In time, both men found themselves involved in the California Arts in Corrections program that is run through a partnership between the state’s arts council and department of corrections.

Just offering such a program, though, might not be enough to affect change. Prisons can have stark racial divides and when artist Katya McCulloch began teaching a block printing course at San Quentin in the early 2000s, white inmates were exuding undue influence on the art room.

“Guys would arrange the desks to barricade themselves a little zone where they could set up their art piece,” said McCulloch, who works for the Santa Cruz-based William James Association. “And it was almost more of by referral or inmate recommendations that people were allowed in the class.”

Another instructor, Steven Emrick used McCulloch’s multi-ethnic class as a wedge to end this dynamic. Instead, a collaborative space was created for artists like: Harrell, who is Black; Ballard, who is white; and Henry Frank, who is of Yurok and Pomo descent and joined the class while serving a 29-year to life sentence.

Class was held every Friday morning from 8 to noon, barring security or other incidents at San Quentin. Frank, who was in the class with Harrell from 2003-09, said that in the art room, factors like race, religion and what the men had done to land in prison fell away “and we’re just artists in there. And that was it.”

Getting out

Harrell went to prison with a seven-year to life sentence with the possibility of parole. But over the years, as he kept falling short with the parole board, freedom seemed elusive. Among those who became disenchanted was Shirley Alexander, a Sacramento resident who met Harrell while he was at Folsom State Prison and married him in 1982.

“It got to a point where I said, ‘You know what? They’d never let him go, though.’” said Alexander, who shares two adult children with Harrell. “I would go to jury duty and I told them exactly what I felt. And they told me to go home because I was – I didn’t believe in the system.”

Laurie Brooks, executive director for the William James Association wasn’t optimistic either. She knew Harrell from his time in McCulloch’s class. “He was always part of the studio,” Brooks said. “I honestly didn’t think he would ever get out.”

But times can change, with Ballard being released in 2011. Frank, who now works for the William James Association, was transferred to a different facility in 2009 and granted parole in 2013. That just left Harrell, who was released in July 2020 after 43 years of incarceration.

Harrell paroled to a halfway house in Oakland, juggling a security job and another position with a San Francisco-based company, Formr.

Formr’s owner Sasha Plotitsa said his company creates “second chances for people and the planet” by employing formerly-incarcerated individuals to create furniture out of construction debris. He remembered Harrell as affable, skilled and easy to work with.

Several months after Harrell’s release from prison, he was allowed to move to Sacramento, where he and Alexander live. “I dreamed of Gary coming home one day and… the dream actually came true,” Alexander said. “So I’m excited. I’m elated that he’s home and he’s experiencing life.”

Living free

Life on the outside for Harrell has been busy. Aside from his job, a security position for FedEx, he invested $4,500 in a trucking business run by another man he was incarcerated with. Harrell has also been trying to create a nonprofit, Community Solutions, that would provide shower services for homeless individuals.

Then there’s his art, which Harrell only has time to do about twice a week now. “I don’t have as much time as I had when I was in prison because I was doing it all day,” Harrell said. “Now, it’s like, ‘Oh, you’re in the real world. Boy, you got to pay the gas and the gas is $300.’”

Harrell has had others helping his art career. In March, a New York City-based program, Right of Return, that helps formerly-incarcerated creative individuals named Harrell as one of six people this year who will receive a $20,000 fellowship. And that was only the latest good thing to happen.

Christine Lashaw, a former Oakland Museum exhibition developer who now does work with an organization called Empowerment Avenue, has helped Harrell to create an artistic biography. “He’s a thinker,” Lashaw said. “He likes to talk not just about his work but about what’s going on in the world.”

Nicole Fleetwood, who didn’t respond to a request for comment, included Harrell and Frank in her exhibition, “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration” that debuted in 2020. Harrell is also part of the Justice Arts Coalition, whose executive director Wendy Jason didn’t reply to an email seeking comment.

Harrell has stayed in contact with McCulloch, who said, “He’s reaching out a bit to get some guidance as he continues to pursue the vision.”

Artistic success is no guarantee of future security for someone who’s reformed their life and overcome hardships.

Another of the men with Harrell in McCulloch’s block printing class at San Quentin, Ronnie Goodman fell back into homelessness upon his release and died at 60 in a San Francisco encampment in August 2020. Goodman’s work appeared posthumously in Fleetwood’s exhibition.

Asked if he’s hopeful for the rest of his life, Harrell initially didn’t hear the question, then puzzled briefly over the word hopeful, before gathering his thoughts.“Every day is a good day,” Harrell said.