Sacramento officers handcuffed a crying 10-year-old girl last year. It didn’t break policy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Sacramento police officers last year put a 10-year-old girl in handcuffs as she sobbed, it did not violate department policy.

That’s because such a policy does not exist, a new audit from the city’s Office of Public Safety Accountability found.

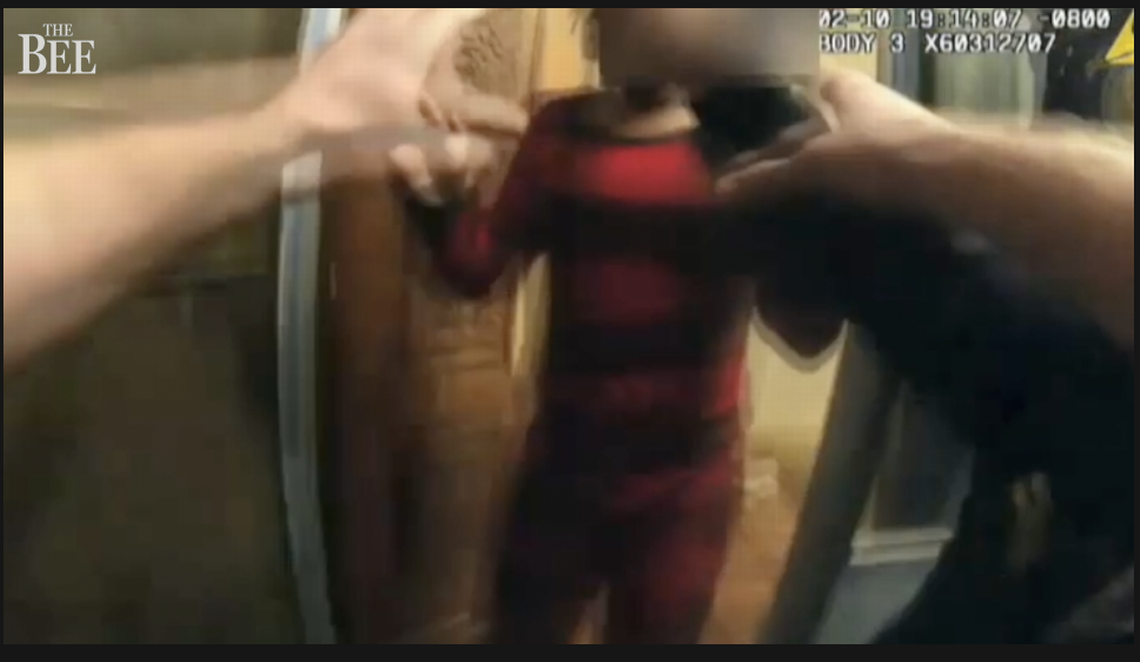

The city’s Inspector General Dwight White and OPSA director LaTesha Watson showed a snippet of body camera footage during Tuesday’s City Council meeting, eliciting tears from several members of the audience. During the video, from Feb. 10, 2022, several white male officers can be seen screaming at people inside to open the door, grabbing the metal screen and forcibly shaking it so hard it looks like it will fall off the hinges.

“Listen we’re gonna kick the door down we don’t wanna do that!” one officer yells.

Eventually a young Black girl, whose face is blurred to protect her identity, emerges in red and black plaid pajamas, sobbing.

“I’m a baby,” she cried.

“Come outside right now,” the officer yelled. “You don’t get to go and hide and turn off the lights that’s not how this works.”

“I’m scared, I’m scared, mommy,” she cried. “I’m scared I don’t know what to do, I don’t know what to do.”

After the girl says she is 10, the officer removes the handcuffs. But by that point the damage had already been done, White said.

“She should’ve never been handcuffed in the first place,” White told the council after the video was done playing. “That will do lifelong trauma ... A racial component did obviously play a role there. If this girl was a different race, she would not have likely been handcuffed by these officers.”

Watson spoke to the mother of the girl, who submitted a formal complaint to the department, which the department dismissed. She was at work five minutes from home the night the police came, she told Watson. The girl was home with her grandmother who was essentially bedridden.

“She advised that her child is now afraid of the police,” Watson said of the mother. “That’s something I don’t want … this is not what we should be doing.”

In a document in response to the audit, Police Chief Kathy Lester said officers went to the house for a probation search related to a stolen car and subsequent firearms investigation.

“The investigation involved a known gang member who was on probation and posted both pictures and videos with firearms,” the document stated. “Upon announcing themselves, they saw people inside, but no one would answer the door. Officers saw a person running through the house turning off the lights. That person came to the door and was immediately detained. The officer asked how old they were, realized the person was only 10 and immediately unhandcuffed them. The duration was appx 30 seconds. The officer had reasonable and articulable concerns for his safety which justified the lawful detention ... no matter how legitimate the circumstances, and no matter the legal justification, SPD understands the sensitive nature of inadvertently creating harm. SPD values and strives to protect the physical and emotional safety of our community and children.”

The document does not identify the girl, and The Bee generally would not identify a juvenile in these circumstances.

Councilwoman Katie Valenzuela said she did not believe that response was sufficient because it did not guarantee policy creation.

“When I was a kid if I was home alone ... I was taught do not answer the door to anybody and I would hide if I heard someone come to the door,” Valenzuela, who is Latina, said. “That video was incredibly disturbing, it just feels like (a policy is) something we should have if we don’t already because that shouldn’t be happening.”

The San Jose Police Department and Baltimore Police Department have policies regarding handcuffing children that the police should use to craft its own, the audit found.

The video, which provided a window into how some officers treat people of color, seemed to strike a chord with the members, as several of them mentioned it throughout the over three-hour-long conversation spanning many topics. Councilwoman Lisa Kaplan, who is white and lives in North Natomas, said she has a daughter around that age who would not have been treated that way.

Police spokespeople declined to provide The Sacramento Bee the names of the officers involved in the call. It is unclear if they were disciplined or still work for the department.

The finding on handcuffs was one of about a dozen recommendations the first-of-its-kind audit found. It revealed “systemic problem” of officers engaging in a pattern of unreasonable stops, searches, and seizures violating community members’ Fourth Amendment right, specifically Black and Latino residents. It included 109 complaint cases of improper search and seizure from June 2020 through June 2023.

Lester said she agreed with parts of the audit, which contain helpful recommendations, but disagreed with the finding that racial bias in search and seizure actions is “systemic.”

Valenzuela, Mayor Darrell Steinberg and Councilwoman Mai Vang pushed her on that.

“If we can’t acknowledge the inequalities in our system, we will have already failed,” Vang said.

After that, Lester said: “I think there’s bias throughout the community. Certainly if it occurs in the community it’s going to occur within the department”

When Valenzuela criticized Lester for taking over a month to respond to the audit, Lester said she values the mission of OPSA.

“Law enforcement has lost credibility and has trust issues in our community,” said Lester, who City Manager Howard Chan appointed as chief in December 2021. “We have great people in this organization we’re a big organization. Sometimes we make mistakes. That’s why its so important to have a layer of accountability ... It serves a very important purpose because we have got to continue to build community trust and without some independent help we are not able to do that.”

Tension surrounds police audit

The city created OPSA in the 1990s to provide an independent oversight of the department, but this was the first time the department released an audit, Steinberg said. That’s likely because the department has a new director, Watson, whom the city hired in 2020. She has 30 years of law enforcement experience, and is a former police chief of Henderson, Nevada.

Steinberg led the creation of the inspector general position after the 2020 Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd and the racial reckoning that followed. White previously independently investigated police misconduct for the city of Chicago.

There was a significant amount of “tension” regarding the audit leading up to Tuesday’s long discussion, Steinberg said. It’s unclear what the tension was regarding. The city has discussed OPSA many times in recent months in closed session, shutting out the public on one of the city’s most important topics. During one of those sessions the council reviewed a large binder of police manuals, Steinberg said.

City Attorney Susana Alacala Wood’s office also submitted a document on the matter to the council, Councilman Eric Guerra said during the meeting. That document has not been attached to the agenda or released to the public. City spokesman Tim Swanson did not immediately provide it to The Bee Wednesday.

Alcala Wood said she reviewed the case law cited in the OPSA audit, to make sure it is accurate, but the police department did not ask her to review the case law in their response document.

“I want to ensure my office respects the police department but I need same respect coming back to my office and I wont stand for anything less,” Watson said. “That’s where the issue is coming in and that’s why we have the problems that we have.”

Watson on April 3 sent a memo to City Manager Howard Chan regarding issues with the police department, according to documents The Bee obtained from a California Public Records Act request. Its contents are unknown however as the city did not yet provide the attachment. The Bee filed the records requests on May 3. Emails between city officials are public records.

The council should discuss the audit again, including specific policies around pat downs, pretextual traffic stops, on Aug. 8, Steinberg said.