Sacramento took family photos, a loved one’s ashes in a sweep. These homeless women ask, ‘Why?’

Her childhood Bible had been in the Winnebago when Sacramento towed it away. Her family photo albums. Pictures of her daughter.

They were irreplaceable. They were gone.

Just about everything Nicole Casper owned was inside that RV. That morning, code enforcement had swarmed onto Opportunity Street without any warning.

She and two neighbors from the Oak Knoll encampment said the city gave them about 15 minutes on Jan. 23 to remove their things from their motor homes; Casper, 42, said she spent most of that time pleading with a code enforcement officer to let her move her RV to a friend’s place. Her friend arrived in his truck minutes after she called him, ready to tow her.

She begged. Couldn’t she move the Winnebago to private property? Please?

The code enforcement officer refused. A city spokeswoman, Kelli Trapani, confirmed that her friend showed up and the city did not allow him to remove the RV. He was not the registered owner.

And so Casper watched the tow truck drive off with her home of three years hooked to the back. She was so stunned that it didn’t even occur to her to get the name of the tow company.

“My whole life,” she said, “was in that trailer.”

As she scrambled over the next week to piece her life back together, she became one of thousands of homeless people who have been trapped in a series of bureaucratic dead-ends that follow Sacramento’s encampment evictions.

The evictions, often referred to as sweeps, have undermined efforts to provide social services and caused waste and delays at the administrative level, previous reporting about a scuttled county shelter on Watt Avenue shows. The city has faced internal pushback: At a Jan. 18 meeting between Sacramento and the county, an email obtained by The Sacramento Bee shows county staff wrote on a whiteboard that “clearings & our association with them” were “NOT WORKING.”

Under a 2018 9th Circuit ruling, if there is no alternative shelter available, homeless people cannot legally be punished for sleeping on public property “on the false premise they had a choice in the matter.” Since the ruling, city workers have continued to push homeless individuals out of their encampments, even as more than 2,000 names typically sit on the waitlist for emergency shelter.

And as Casper and her former neighbors on Opportunity Street have learned, the city’s tow orders can completely upend an already precarious life.

Casper said the unannounced sweep felt more like a punishment than anything else. She asked: What was the point of the city removing her shelter?

“I was houseless,” she said, “but now I’m homeless.”

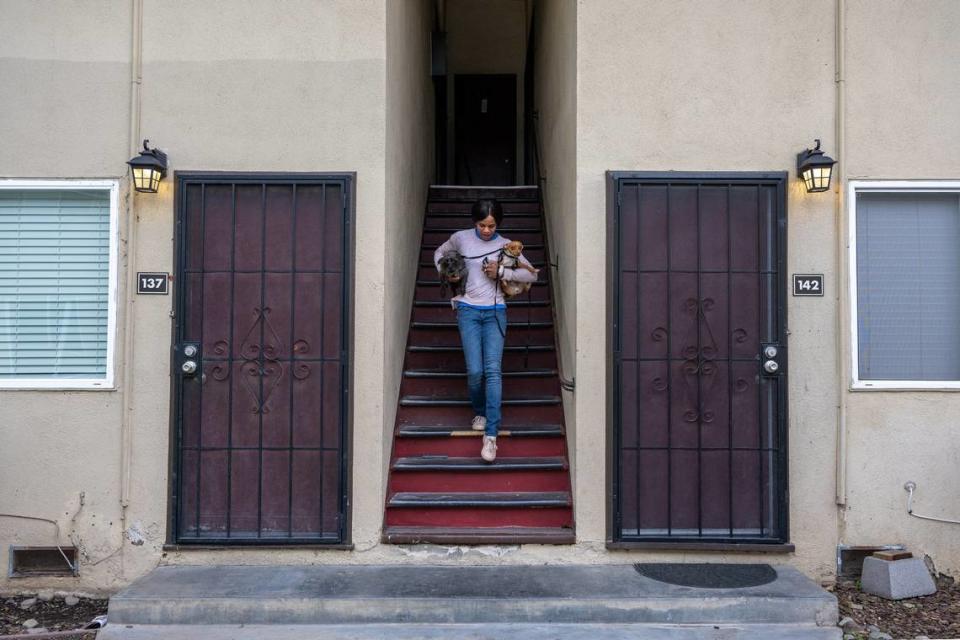

She and her two small dogs, Gucci and Yoda, have been able to stay temporarily in her friend’s apartment — but the friend has a wife and four children, and all he could offer her was a temporary space on the floor. She’s said she’s afraid that when she must leave that apartment, she’ll end up in a tent.

It didn’t make sense, she said, for the city to leave her with nothing. She didn’t even have time to grab her dogs’ leashes from the RV, and had to waste money buying new ones.

She had a question for Sacramento: “Who wins in this?”

Homeless sweep breaks social ties

A document provided by one tow company showed that a notice was mailed to the registered owner of Casper’s RV on Jan. 25, two days after the Winnebago was wheeled away. Like many homeless people, Casper isn’t the registered owner of the RV she lived in, and so she never received a notice of any kind.

Casper knew that because she wasn’t registered, she was unlikely to see her things again. She would have to start over, she thought. She said the city didn’t offer her a temporary shelter as they seized the closest thing to a stable home that she’d had in years.

The city said it couldn’t confirm or deny whether Casper was offered any services. Trapani said, “We don’t have information on this specific instance.” She said two families from the street went into a temporary shelter.

Casper did not. And the Winnebago — the shelter that had seemed so permanent to her — was gone.

For two friends on Opportunity Street whose homes were taken — Casper and Nicole Stuart — cherished belongings were suddenly ensnared in a thicket of red tape.

And their little community immediately splintered. Stuart spent the first five nights squeezed in the RV owned by another woman from Opportunity Street who’s become a surrogate mother to her. But Casper was on her own, forced out of her Winnebago and into her friend’s overcrowded apartment. After the first five nights, Stuart, too, moved away, into her dad’s tiny trailer.

Casper and Stuart tried to recover their property from their homes in the week after the sweep. Both had no claim to their belongings on paper. Under state law, the registered owner of a vehicle “or his or her agent” has the right to retrieve their items from an impound lot without a charge. But, because these women aren’t the registered owners of the vehicles in which they lived, each just had to hope that someone at the tow company would take pity on them.

And they didn’t have much time to find a sympathetic ear.

Because in just a few weeks, their homes and everything inside them would be administratively reclassified as “garbage” and discarded.

Bureaucracy and helplessness

To justify the sweep on Jan. 23, Sacramento pointed to state law. Paperwork sent to one tow truck company said Casper’s Winnebago was in violation of Vehicle Code section 22651(o).

In other words, the registration expired more than six months ago.

Trapani confirmed that the city ordered immediate tows of vehicles violating that section of code on Jan. 23. Others on the road were given a 72-hour notice. All told, 13 vehicles were towed from Opportunity Street and the surrounding area that day.

Trapani said that code enforcement officers “do their best” to let people unload their things, and that officers often provide assistance. “Sacramento,” she said, “strives to treat all people with dignity and respect.”

Usually, she said, homeless individuals get 30 minutes to an hour to unpack. She added, “The time the occupant has to remove their belongings varies (based) on whether the tow truck is on scene or not.”

Casper, Stuart and Traci, Stuart’s surrogate mother — who asked that her last name be withheld to protect her safety — said that code enforcement gave everyone who was being towed about 15 minutes to retrieve things from the RVs and trailers they called home. While Casper said she spent most of the allotted time desperately trying to persuade the code enforcement officer to let her friend tow her to his own private land, Stuart said she spent most of that time warning others on the street.

Both women lost almost everything.

Even if Stuart had not spent the time warning her neighbors, those 15 minutes, she said, weren’t enough to unpack over a year of her life. Her mother-in-law’s ashes and her late husband’s prayer beads were still inside the trailer as she watched a driver tow it away. She wasn’t sure she’d ever see them again.

At the tow lot

Traci and Stuart drove into the parking lot of the tow company a few hours after the sweep. Traci got out of the truck, angry. She wanted to smoke a cigarette to calm her nerves, but neither of them had a light. She tucked the cigarette behind her ear, they both braced themselves, and they walked inside.

Stuart stood under fluorescent office lights and met with what, under the circumstances, seemed like a bit of luck. Stuart explained her situation to Tim Post, a manager at College Oak Towing, and he looked at her kindly. When he asked for her ID, she had it. Thankfully, she’d grabbed her wallet from inside the trailer before the city took possession.

Post told her almost immediately that she would be allowed to get her property back. A mercy.

“Let’s go out and try to find this thing,” he said.

“It’s one of,” he paused, “too many.”

‘A sea of trailers’

Post led the women past the front desk, down a hallway and out a back door to the impound lot. Like he said, it was full of trailers and RVs. They were all dilapidated. Some were badly burned. A few had missing panels jerry-rigged with wood.

Walking through the lot in East Del Paso Heights, Stuart stared right through them. She didn’t see the falling-down motor homes; she just saw homes. And she saw the people who’d been kicked out of them.

Her eyes filled with tears. She turned to Traci and said, “It’s like a sea of trailers.”

All those people who had lived inside them — where were they now?

She started to cry.

Traci walked through the lot beside her, jumpy, the cigarette still behind her ear. She saw the same thing, and she cut right to the consequences.

“This,” Traci said, “is a graveyard.”

A loved one’s ashes taken by Sacramento

They found Stuart’s trailer among all the other homes. Post told Traci to pull her truck around so the women could load it up. Stuart started with the back of her trailer — clothes, purses, shoes that she loved. A pair of strappy sandals, pink and sparkling. She’d thrifted just about everything, she said, and it had taken her years to scrape together this wardrobe. Her dogs’ kennels were still inside her home.

As Stuart was sorting through her things, she started to cry again.

“I’m so stressed out,” she said, talking fast. “What are you gonna do? It’s cold out there at night. Like, what are you gonna do? And they just want to tell me to go to a shelter? Going to a shelter for a single female — that’s the worst thing to do, is send me to a shelter.”

Her trailer had four solid walls and a door that locked. She had her autonomy in that trailer. In a city shelter, she’d have to follow sometimes stringent and even patronizing rules, and she would lose at least some — maybe even all — of her privacy.

“I’m safe in my own house,” she said. “I lock my own door. I know what’s going on around me.”

Post stood at a slight distance and watched Traci and Stuart for about an hour; the women fit whatever they could into Traci’s truck. Stuart found her mother-in-law’s ashes, and the delicate white box that held her late husband’s prayer beads.

He died in August 2021, and she was relieved that at least she didn’t have to lose this little piece of him. “He was my everything,” she said. “He didn’t deserve to go.” She had feared that morning that she would never hold them in her hands again.

Hours earlier, she said she asked a code enforcement officer on Opportunity Street whether she could retrieve these items before the trailer was towed. The officer, she said, replied “no.” “They wouldn’t even let me get a blanket,” she said, referring to the thick blue blanket she’d just stashed in Traci’s truck.

She repeated it, still bewildered: “Girl,” she said, “they would not let me take a blanket.”

Traci’s pickup wasn’t big enough for everything. They would have to leave so much behind, and they weren’t certain they could make it back before the rest was destroyed. Stuart would spend that night and the next four nights in Traci and her husband’s cramped RV, frantically searching Craigslist for a free or cheap trailer.

On Sunday, five days after the sweep, Stuart moved out of the RV and into her dad’s tiny trailer. Their little Opportunity Street family had fractured once more.

And the displacement continued. When Traci moved her RV to Traction Avenue, she said, she was parked for about 30 minutes when she received an unwelcome document.

A 72-hour notice of a sweep.

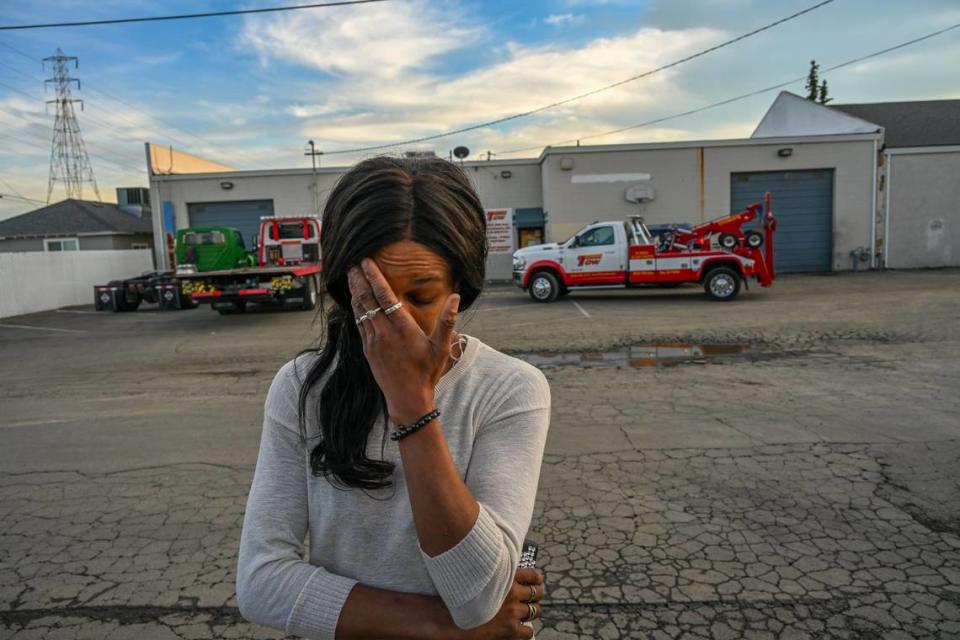

As Traci prepared to move again, Casper was still trying to get her family photos back. “No” was the first response. Standing in the cold outside her friend’s apartment with her two shivering little dogs, Casper called the tow yard again. “No,” said the woman on the other end of the line.

She was beginning to lose hope.

A life labeled garbage

The fact that Casper even knew which company to call was something like a lucky break. A friend on Opportunity Street caught the company name on the truck that took Casper’s Winnebago. She hadn’t had the wherewithal to write it down, and the city gave her no documentation.

She called Chima’s Tow multiple times, and each time, she said staff told her that she would not be able to recover anything from the RV if she were not the registered owner. She almost didn’t even try showing up at the place. She doesn’t own a car, and the lot was 12 miles from her friend’s apartment. What was the point of going all the way down there if they were just going to turn her away?

Still, the Monday after the sweep, she got a ride from her friend to the lot in Colonial Manor.

She walked into the front office of the tow company, which has a red sign on the wall that says proof of ownership and a photo ID are required to access impounded vehicles. Her prospects seemed grim. And, standing behind the red-and-white front desk, Iran Chima at first told the small woman the exact same thing she had been told on the phone. Because she wasn’t the registered owner, she couldn’t touch anything in the Winnebago. Not even her own childhood photos.

Casper asked him what would happen to her RV, and Chima told her matter-of-factly, “It gets crushed.”

He produced a form that indicated when her home would become a heap. Chima pointed to the date, and said he would ultimately keep the vehicle for just over two weeks. The Winnebago was set to be destroyed on Feb. 8. In the days before that, everything inside — the clothes, the family photo albums, the Bible she’d had for her whole life — would be thrown out.

A Bee reporter asked him why Casper couldn’t access her belongings after they became garbage on paper but before they were actually thrown away.

He shifted. He later explained to two employees, “If we gotta toss it, we might as well give it to her.” They nodded.

Ultimately, Chima offered Casper a deal. He told her that she could come back Feb. 6 if she agreed to completely empty the trailer that morning, before it was crushed on Feb. 8.

“Fair?” he asked her.

Nothing about the situation seemed particularly fair to her. Sacramento had confiscated her home, left her without a shelter and forced her to plead for her own family photos, all of which were on the cusp of being thrown in the trash. She said she never even spoke to the social services worker that day on Opportunity Street, and that he drove away as she tried to flag him down. She’d called a reporter as a last resort. She thought the sweeps were inhumane, but that maybe if people heard her story, Sacramento could change. The city, she had said, “would treat a dog better.”

It was all humiliating.

Now, considering Chima’s deal that she unpack her entire home, she paused. She wasn’t sure how she would manage to transport everything. Casper doesn’t have the money to rent a truck or a moving van. Her friend had given her a ride that day, and he might be willing to help her, but his car is just a sedan.

Still, this offer from Chima was a “yes” when all she’d heard before was “no.”

So she thanked him.