'Sacrificed for the greater good': The death of Tyre Nichols in Memphis

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story is a collaboration between USA TODAY and The Commercial Appeal as part of the documentary video series “States of America.” The full episode of “States of America” exploring the death of Tyre Nichols and what went wrong in Memphis premieres at 8 p.m. and 10 p.m EST on April 7 on USA TODAY NETWORK’s streaming channel available on Samsung TV Plus (Channel 1023), Roku, Plex and many more. You can also catch our full series on YouTube.

RowVaughn Wells wanted all five of her son's accused killers to look her in the eyes.

In a Shelby County courtroom brimming with reporters, five former Memphis police officers, flanked by attorneys, walked past four rows for public seating and faced the judge.

All five pled "not guilty" to beating RowVaughn Wells' son, Tyre Nichols, beyond recognition on the night of Jan. 7 in an altercation now said to be worse than the beating of Rodney King — and not solely because Nichols, unlike King, would die as a result of the beating three days later.

It was worse, because as one Memphian put it, "there's a code," between Black men.

Nichols cried out for RowVaughn Wells three times as the five officers took turns delivering one blow after another to his face and chest. When a grown man cries out for his mother, according to the code, that's a sign to stop. The officers didn't.

And now, all five men lowered their eyes when they walked past the Wells family and out of the cramped court room that mid-February morning.

"This nightmare that I'm going through right now ... I'm waiting for someone to come wake me up," RowVaughn Wells said following the arraignment.

Sandwiched between Rodney Wells, Nichols' stepfather, and Ben Crump, the family's attorney, she acknowledged her nightmare was real. She knows Nichols isn't coming home. And she wants his five accused killers to at least look at her, as she walks through a nightmare with a national audience in tow.

She's holding it together, she said, because of the wave of condolences, prayers, and support that has washed over her family.

But, another facet of Nichols' murder is holding her up as well.

"I have to always keep in mind that my son was sacrificed for the greater good. That's what's holding me up. That's what's keeping me together," she said.

It's not clear what the greater good will look like for Memphis and policing.

Elected officials are calling for a federal "pattern-or-practice" investigation into Memphis police. Citizens are pushing for the end of certain types of traffic stops. The U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation are now looking into whether Nichols' civil rights were violated. And, the city's push to hire hundreds of new officers has drawn national scrutiny.

The work to ensure Nichols' sacrifice has meaning is just beginning in Memphis.

'I honestly never thought it would happen to him'

The first few days after Nichols' death on Jan. 10 were quiet.

Before the image of Nichols' swollen face raced across social media, before Crump, the well-established civil rights attorney, came to Memphis, and before the demand to release any and all footage from the police altercation that led to Nichols' death reached a fever-pitch, the news that Memphis police had killed a fourth citizen in two months didn't initially spark outrage.

On Twitter, the Memphis Police Department issued a standard tweet the morning after Nichols was taken to a nearby hospital for treatment; it described a traffic stop for alleged reckless driving.

"As officers approached the driver of the vehicle, a confrontation occurred, and the suspect fled the scene on foot," the tweet read.

Initial reports gleaned from the police tweet parroted key phrases: Altercation, reckless driving, shortness of breath, died from injuries sustained. All five officers involved in the fatal interaction — Tadarrius Bean, Justin Smith, Emmitt Martin III, Demetrius Haley and Desmond Mills, Jr. — were placed on leave, a standard administrative procedure for the Memphis Police Department in use-of-force investigations.

Days after his death, the public learned more about Nichols. The picture of who he was as a person was coming together, and it was at odds with the narrative that a traffic stop would lead to a physical altercation.

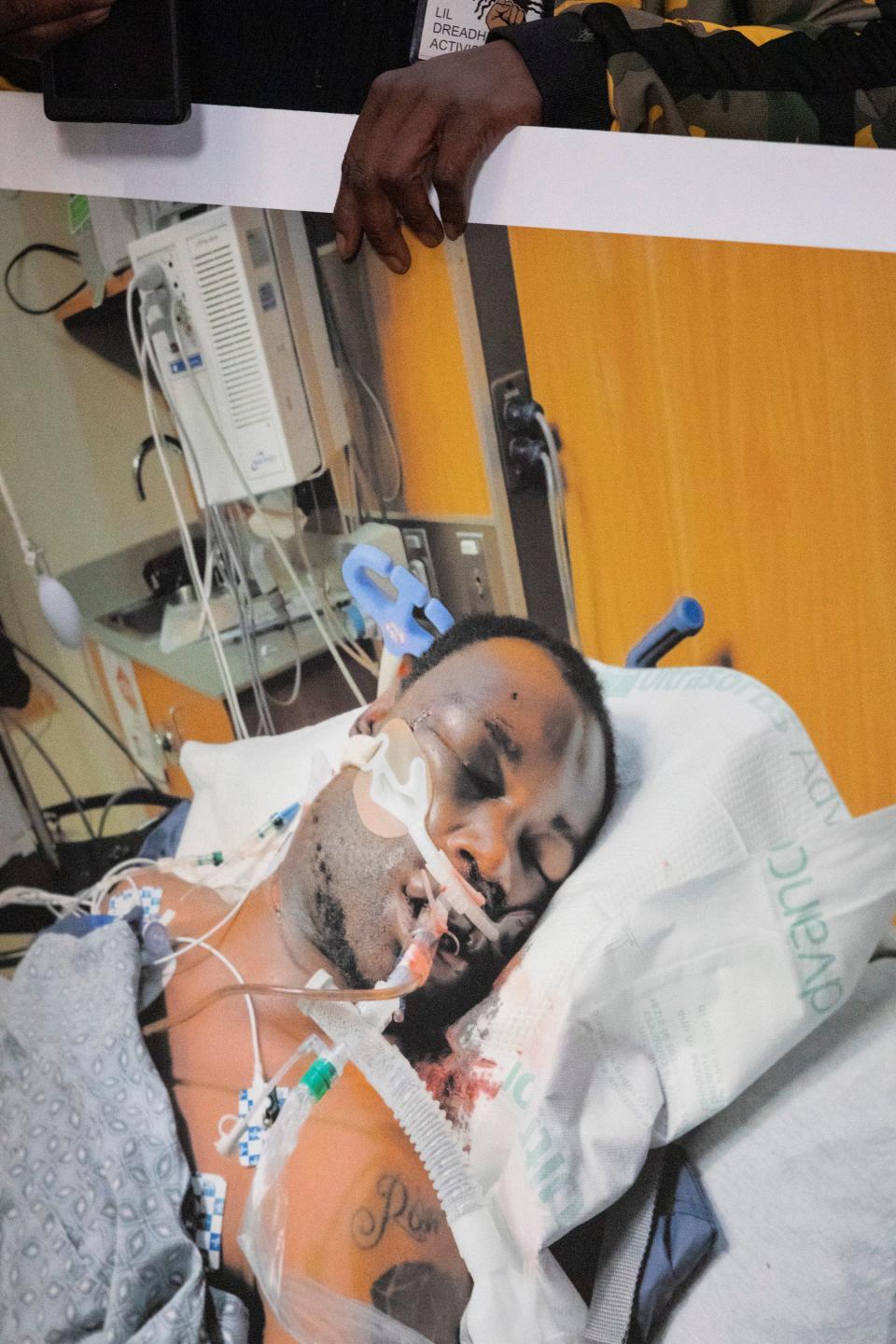

Once the photo of Nichols — unconscious in a hospital bed, blood visible on the tube that was forcing air into his lungs — surfaced, questions around what happened the night of Jan. 7 went from a simmer to rolling boil.

In the absence of a complete picture, family and friends of Nichols were already certain of one thing: If Nichols ran from the police, he had a valid reason.

"If he did run, it's because he was scared," said Chris Volkner in the days after Nichols' death. "He's never had to deal with police, and as a Black man he knows better than to fight cops. He was very vocal about BLM. I honestly never thought it would happen to him."

Volkner added that Nichols had never been in trouble with law enforcement, not as a young adult in Sacramento, and certainly not in Memphis, where he had moved in 2020 in the spirit of starting fresh. When he wasn't working at FedEx, he was skateboarding, or chasing Tennessee sunsets with his camera.

As families and friends struggled to make sense of exactly how a confrontation with such a mild-mannered and free-spirited person could lead to his death, indications that something went lethally wrong in Memphis began to accumulate.

A small protest bubbled up outside of the precinct where the five officers were stationed. Nichols' family launched a fundraiser to help send his body back to Sacramento. Activists who routinely monitor police joined Nichols' family and friends in demanding an answer.

As pressure for accountability swelled, multiple events solidified the suspicion among some that the circumstances around Nichols' death were criminal.

On Jan. 15, Memphis police Chief Cerelyn "C.J." Davis announced officers involved in the traffic stop were facing disciplinary action. The announcement in itself was unusual — open investigations into police force usually are not commented on by police.

"After reviewing various sources of information involving this incident, I have found that it is necessary to take immediate and appropriate action," Davis said.

On Jan. 16, Crump was retained by the Nichols family. The retainment alone carried significance; Crump's law firm has represented multiple families who lost loved ones to police or racially-motivated violence, including the families of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery.

His firm immediately called for the release of all footage from the officers' body-worn cameras.

With questions mounting and the threat of civil unrest looming, Davis and Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland issued a joint statement on Jan. 17: the city would, sooner than later, release the footage of the events that led up to Nichols' death.

Three days after the joint announcement, the police department announced all five officers that beat Nichols were found to have violated several department policies. All five were fired, and within a few days, all five would be charged with second-degree murder.

How Memphis met a defining moment

Many predicted Memphis would burn when the world found out what happened to Nichols.

On Fri. Jan, 27, the city released more than an hour of footage from the night Nichols was pulled over. The footage was pulled from three officers' body-worn cameras and a police-operated surveillance camera. The latter provided an overhead view of the corner where Nichols would speak his last words before slipping into unconsciousness.

In the 17 days between Nichols' death and the release of the footage from that night, national and international media had picked up that something went terribly wrong in Memphis, and now a 29 year old who had only ever been in trouble for traffic violations was dead. Outlets tripped over one another in a race to predict rioting.

At a candlelight vigil the night before the video release, RowVaughn Wells implored the hundreds gathered to peacefully demonstrate.

In Memphis, businesses shuttered early and public officials all the way up to President Joe Biden preemptively condemned any violence that may erupt following the release of the footage.

But the moment was met with a peaceful protest.

Some 150 protestors, and almost as many reporters, learned what happened to Nichols as they glanced at their phones while marching down Riverside Drive in Downtown Memphis.

Eventually, the crowd scrambled up an embankment to Crump Avenue, which led directly to the Memphis-Arkansas Bridge that carries I-55 across the Mississippi River. They remained there for several hours, cycling through chants for justice and calling for an end to police violence.

Halting commerce was the goal, and protestors chanted, "They taking our lives, we taking they money," as semi trucks stayed stalled by bands of protestors linking arms across all four lanes of traffic across the river.

By 10 p.m., most protestors were back at the rendezvous site. Pizza and bottles of water were passed around as some discussed what the next steps were.

For all the trepidation around the release of the footage, Memphians met the moment by refusing to meet national expectations.

Any person involved in the protests might give one or more reasons: RowVaughn Wells called for peace. The weather that night was cold and rainy. No one wanted to add to the heartache that had already wrapped Memphis in a bear-hug it didn't ask for.

One labor organizer, Jayanni Webster, would later say that the refusal to flood the streets and riot was, in a way, Memphis taking back its own narrative.

"Anytime you have a system, even if it's an unnamed system, that's dictating what you should do, you should do the opposite," Webster said. "If you think we are violent here, that we'll burn down our city...you're wrong."

Breaking the code

Like other major cities, Memphis experienced an uptick in violent crimes during the pandemic. And like other cities, local elected officials cited a need for hundreds of new officers.

The brutality factor in Nichols' death may have prompted a closer look at the relationship between Memphis police and the communities they serve, and the qualities newer recruits were bringing to the force, but for many wariness was already a feature in their interactions with police.

Bennie Smith, a prolific software developer and current election commissioner for Shelby County, knew which officers would arrest you and which ones would simply beat you, let you go, and take your cash.

"We called them 'friendlies'," Smith said.

The five officers who beat Nichols were members of the "SCORPION" unit, one of the many specialized units tasked with patrolling areas of Memphis considered hot spots for violent crime. SCORPION stands for Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods.

The unit was relatively new, started by Davis after she came to Memphis from Durham, North Carolina, where she also served as police chief.

And while the unit was new, its reported use of aggressive tactics was not surprising to Smith; it was another iteration of "jump-and-grab" units that marked his childhood in Memphis' Binghampton neighborhood.

"There was no talking," Smith said. "They jumped out, they grabbed you ... and that's just like how we got robbed. It was the same way — a robber would jump out and grab you."

Smith's neighborhood was marked by violence in his adolescence. The lack of opportunity, he explained, meant you had but a handful of ways to escape: rap your way out, hoop your way out, hustle your way out or, in Smith's case, think your way out.

Smith knows there is a push-pull relationship between some of Memphis' most vulnerable neighborhoods. A lot of older folks, he said, want to see more police. Many in neighborhoods grow up to become officers themselves.

But, there's a code, what should be an inherent instinct to let up at some point, especially when a grown man cries out for his mother. That officers ignored those pleas is inhumane to Smith.

"To see Black guys doing this is what hurt the most. You got the same code inside of you, you have the same DNA," Smith said.

The footage of the officers beating Nichols reminded Smith of a time when he was jumped at the end of his street. He called out for his mom too.

"When you hear a guy cry out for his mama... you got to let up, man. And they know this. These guys, they know this," Smith said.

On the day of arraignment, Smith joined several elected officials and longtime community activists at the NAACP's Memphis headquarters. There, the group called for federal officials to look more thoroughly into Memphis police policies.

To Alvin Davis, a former lieutenant with Memphis police who oversaw recruitment efforts under Davis, the actions of the officers showed a pronounced lack of training and discipline. The calls for further scrutiny of Memphis' police doesn't surprise him; he retired from the department early over an increasing frustration in recruiting processes.

"We use to joke around and say, 'No recruit left behind," Alvin Davis said.

Of the five officers that beat Nichols, the most tenured officer was hired in 2017. Even still, Davis said, a lack of training is one thing, but the outright brutality has stunned him and others on the police force.

"No one understands it," Alvin Davis said. "No one is saying there was a reason or that it was justifiable or anything like that," he said.

Alvin Davis' concern for the police department deepens by the day. Too many good lieutenants, sergeants, and officers were leaving, demoralized by what the job has become. Too many new recruits, he said, were coming in under relaxed standards and motivated by a $15,000 signing bonus.

"And I know that because many, not all but many, would ask, 'How long do I have to work here to get the money,'" he said.

Crime rates in Memphis have fluctuated over the past few years, sometimes in tandem with economic blows like the fist 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. In his years on the force, Alvin Davis has never seen people this emboldened when they commit crimes, from carjackings to drag racing to road rage episodes that erupt in gunfire along the interstate.

To say that Memphis as a whole doesn't want more police is inaccurate, he said. But between the quality of some of the new recruits, and a police force he describes as demoralized, "no one really knows what to do anymore."

"It's just not that job that you're proud of anymore more," he said. "You know, you say the “best in blue”... but you start seeing that it's diluted. It's not a job that you're really proud of anymore."

The road ahead in Memphis

Following hours of debate and public input, the Memphis City Council passed five public safety ordinances that cover myriad aspects of policing from data transparency to the end of using unmarked police cars during traffic stops.

Community organizers that have asked for such measures enjoyed a short victory: though all five of the ordinances passed, it's now possible that all five ordinances could be consolidated into one ordinance. The new singular ordinance could have provisions repealed and replaced.

The sole ordinance would be called the "Tyre Nichols Justice in Policing Ordinance," even though Nichols' family has spoken out against the ordinance, expressing concern that the proposal will contain a watered-down version of reform. The vote on the singular ordinance will happen in mid-April.

The stage for an ongoing push for police reform is set in Memphis, bookended by anxiety over the rate of violent crime in Memphis and the need for significant investments in Memphis communities to better a person's chances of "making it out alive," as Smith would say.

LJ Abraham, a community organizer who has long-standing criticisms of the police, said she sees glimmers of hope. Those glimmers, she said, are found in things like a new prosecutor who has shown a willingness to charge police with crimes, or the potential for federal intervention within the police department.

But none of it will bring back Nichols. And the tango between police and communities that experience a higher rate of violent crime will continue.

If nothing else, Abraham said, maybe more will understand that, "police protect and serve each other."

"It's been proven in Memphis that more police doesn't equate to less crime," Abraham said. "At the end of the day, when they put on that uniform and that badge, then they're just looking at each other and what they can do to protect each other."

Whether significant reforms are inevitable remains to be seen. But the death of Nichols has effectively inked another chapter of pronounced trauma in a city that has already endured more than its fair share.

That chapter tells a story of a skinny skateboarder and goofy father, just trying to make his way home before he's stopped by officers clad in hoodies, rushing at him from unmarked cars.

Nichols sister, Keyana Dixon, is trying to listen to RowVaughn Wells when she says, "something good will come out of this," but she's not ready yet.

Nichols may now belong to the world as a symbol, a reminder to keep pushing. But for now, Nichols is still the baby brother that she helped raise, the aspiring photographer and renowned goofball that "the world saw get murdered."

"I called him a good kid," Dixon said. "He was a grown man, but he was a good kid. He was always a good kid. His morals and his values and the way he treated people ... he would never step on anybody's toes to get ahead. And that's how I knew he would be great."

Micaela Watts is a reporter for The Commercial Appeal who covers issues to tied to access and equity. She can be reached at micaela.watts@commercialappeal.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What happened in Memphis when police pulled over Tyre Nichols