In sad irony, Ky library restricts LGBTQ book but houses history of gay icon | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Earlier this year, the small Clark County Public Library had a bit of a kerfuffle.

Someone complained about a book that in these challenging days has been frequently challenged: “Gender Queer,” an award-winning young adult graphic novel by Maia Kobabe about coming out as non-binary. It’s now the most banned book in the country, according to National Public Radio.

At a contentious meeting In December, the library’s Board of Trustees voted to put the book in the restricted section, which means anyone under the age of 18 would have to have their parent’s permission to check it out.

But far more upsetting to Winchester residents like Chuck Witt is that the board also took the American Library Association’s Freedom to Read policy statement out of their bylaws. It says in part: “It is in the public interest for publishers and librarians to make available the widest diversity of views and expressions, including those that are unorthodox, unpopular, or considered dangerous by the majority.”

“The American Library Association Freedom to Read position typifies what public libraries should aspire to,” Witt told me. “Library boards, composed of typically small numbers of people, should not take it upon themselves to restrict reading materials without due process and by creating false narratives about the material. Book bans are expanding geometrically across the country to the detriment of everyone and smacks of literary McCarthyism.”

In Kentucky there has been an increase in banned books and in attempts by the General Assembly to put politicians in charge of our libraries.

Doug Christopher is president of the library board, and said the library had an existing policy that required any movie with an R rating to also be restricted to anyone under 18 without parental permission.

“Based on the sexually explicit images in that particular book, we chose to put the same restriction on the book,” Christopher said.

Then, as they did an annual reviews of policies, the trustees noticed that one of the ALA Freedom to Read statements said there should be no age restriction on any resource in the library.

“In our review of the policy, I thought we were not in agreement with that particular position because we were restricting R rated movies,” Christopher said. “I thought if we’re not going to abide by their guidelines, it didn’t appear appropriate to have their guidelines in our collection policy. That was it in a nutshell.”

That’s a logical and not altogether unreasonable position, because lots of parents don’t want their young children opening a book to see depictions of oral sex or a first trip to the gynecologist, even in a coming of age story. But it opens the door to book banning — a disconcertingly frequent practice these days — and can quickly descend into irrationality, particularly given what kids can find on their ubiquitous cell phones.

Ironic history

The whole situation is ironic because the Clark County Library is the repository of history about one of the most important moments in LGBTQ history. (As I frequently note, Kentucky contains multitudes.)

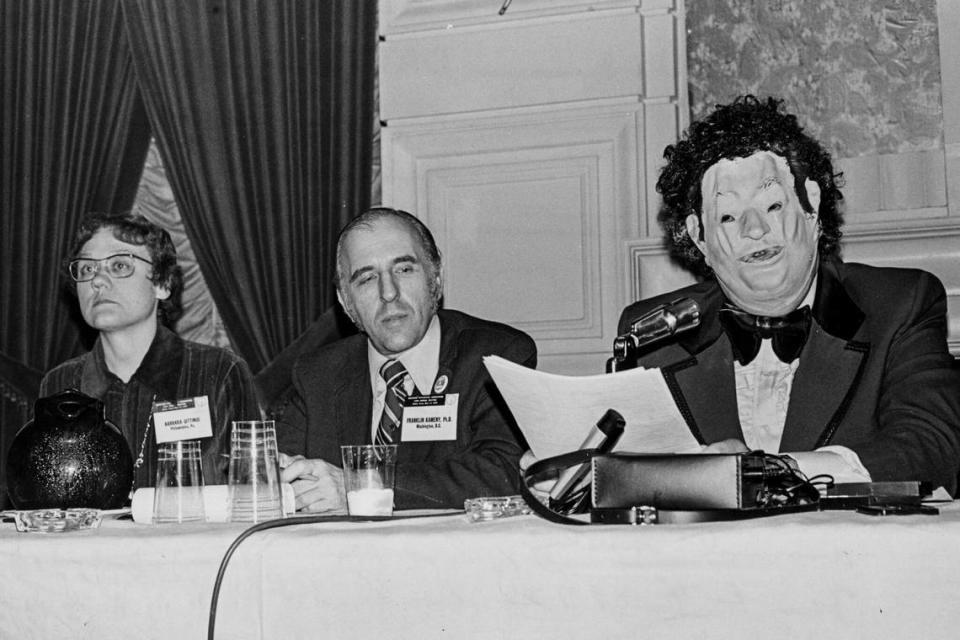

In 1972, Winchester native and psychiatrist John Fryer spoke at the annual American Psychiatric Association. He wore a rubber mask because he was scared that what he was about to ask would ruin his career.

“I am a homosexual,” Fryer said. “I am a psychiatrist.”

In his speech, he begged the APA to take homosexuality off the list of mental illnesses. By remaining closeted, he told his fellow gay psychiatrists, “we are taking an even bigger risk … in not living fully our humanity, with all of the lessons it has to teach all the other humans around us.”

They agreed in 1973 and, thanks to Fryer, changed history for millions of people.

Fryer had attended Transylvania as an undergraduate but spent his childhood in Winchester. The Clark County Library is where researcher Jon Coleman found Fryer’s yearbook photos and his family in local genealogy collections.

“He has been celebrated nationally because he’s an extraordinarily important advocate for humanizing and destigmatizing LGBTQ people,” said Coleman, who is co-founder and executive director of the Faulkner Morgan archive, a grassroots archive of Kentucky’s LGBTQ history.

Coleman has been following the Clark County book debate closely.

“It’s pretty clear that this is nothing about protecting kids, it’s simply the homophobia that John Fryer was protesting 50 years ago,” Coleman said.

Bigger issues

If, like me, you thought we’d made more progress on LGBTQ issues, the last couple of years have proved us wrong. Book bans are one way, along with others, we’ve seen that intolerance writ large.

Book bans about “sexual content” are often about far larger issues.

A Missouri school board is set to ban the Pulitzer-Prize winning “Maus,” a graphic novel about the Holocaust, because of a law banning “explicitly sexual material.” The material in Maus? A naked dead body in a bathtub after a suicide. Nor is it the first time the book has been flagged under those grounds.

In the Washington Post, Maus author Art Spiegelman noted that the sexual material call is a ruse because people are uncomfortable with genocide. The repeated targeting of “Maus” over alleged sexual content, Spiegelman lamented, is a mere pretext. “It was the other things making them uncomfortable, like genocide,” he said. “I just tried to make them clean and understandable, which is the purpose of storytelling with pictures.”

It’s clear that what such bans are really about is the desire to control our access to much bigger ideas, like LGBTQ issues or race. In South Carolina, there was a horrifying instance of an AP English teacher whose class was shut down after students complained about videos connected to a Ta-Nehisi Coates book, “Between the World and Me” about growing up poor and Black in Baltimore.

“I was incredibly uncomfortable throughout both videos, and was in shock that she would do something illegal like that,” the student wrote, adding parenthetically “I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina.”

Laugh until you cry, folks.

It remains to be seen if the Clark Library restriction is a one-off or part of a larger attempt to silence controversial topics that shouldn’t even be controversial. As I’ve written before, book bans are a way to try to control narratives some people don’t like, and sadly, even after the valiant work of people like Clark Countian John Fryer, LGBTQ rights seem to be among them.