This is the saga of Arizona's famous stolen de Kooning painting

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The painting was obviously stolen.

David Van Auker stashed it behind his couch, wrapped in a blanket, and got out his Colt .38.

Then he sat down with the gun in his lap and tried to make sense of what had happened during the past 12 hours.

He had picked up the oil painting of a nude woman that morning as part of an estate sale. At the time he knew only that there was a house full of furniture and other belongings, and he had agreed to take it all for cash. But he liked that one painting.

He leaned it against a post in the antique and furniture store he co-owned in Silver City, New Mexico. Customers stopped by, and almost immediately they started to notice: Is that a real de Kooning? The Dutch-American artist was a master abstract expressionist. One customer even offered Van Auker$200,000 for it.

Van Auker started Googling. By that afternoon, he had come to a conclusion he still could hardly believe.

The painting he had purchased for $200 matched a photo of a long-lost de Kooning that had been stolen from the University of Arizona more than 30 years earlier. It was estimated to be worth more than $100 million.

He called the university’s art museum — fully aware he sounded like an idiot — but convinced he had the real thing. The museum curator seemed optimistic. She asked him to email photos of the painting, which he did. She thanked him. Then he heard nothing more.

Word travels fast in Silver City, a tight-knit arts community in southwestern New Mexico. His business partner, Buck Burns, knew they needed to hide the painting, but the entire store had only one interior room with a lock. So that's where he stashed the masterpiece: in the small bathroom, right next to the toilet.

At 5 o’clock, they closed the store, unsure what to do. They didn’t want to leave the painting overnight. So Van Auker took it home.

Paranoia set in. Who knows how many people had seen the painting, and everyone knew where he lived, 6 miles out of town off a winding road in the middle of the forest. It was a windy night. The brush and scrape of tree branches jangled his nerves. He imagined intruders approaching and kicking in his door. He loaded three guns. As well as the gun in his lap, he had an antique .22 caliber on the entry table and a 9 mm pistol on the nightstand.

Then he picked up the phone and dialed another phone number. To research the painting, Van Auker had read an old Arizona Republic article that recapped the 1985 theft. Now, he dialed the number at the bottom of the story. The number rang at a desk in the newsroom. The voicemail prompt beeped.

“This may be totally ridiculous and stupid,” Van Auker saidon the voicemail. “But I purchased a painting at an estate a couple of days ago, and when I was doing some research on it, I found your story on the U of A missing de Kooning painting. And it’s exactly the painting I have.”

How the de Kooning ended up in Arizona

Van Auker had learned about de Kooning while studying interior design in college.

A trained painter in the Netherlands, de Kooning stole away on a ship bound for the United States in 1926. He worked as housepainter before establishing himself as a commercial artist in New York City.

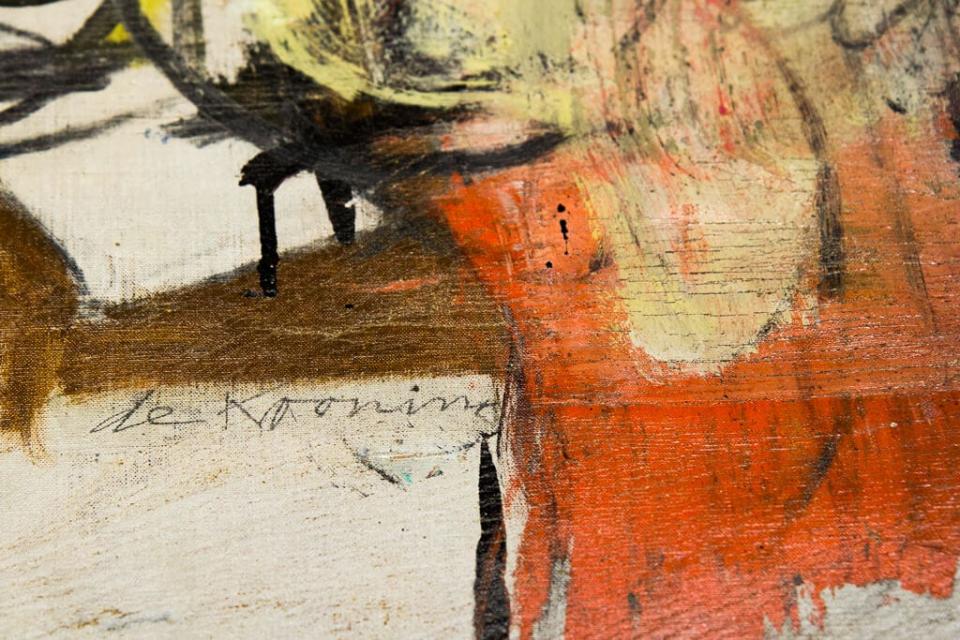

He was known as an “artist’s artist,” with a distinctive brush stroke that moved paint quickly around the canvas. He used charcoal to outline and emphasize.

De Kooning shocked the art world in the 1950s with a series known as the “Women” paintings. They were dramatic, aggressive depictions of women with big mouths, wide eyes and exaggerated breasts.

In the winter of 1954-55, he made an oil painting of a nude woman, her breasts accented in yellow. He added hues of turquoise, green, crimson and orange against a neutral background.

De Kooning sold the work, titled “Woman-Ochre," along with several other paintings to Martha Jackson, a New York City art gallery owner.

Jackson exhibited “Woman-Ochre” in 1955 and loaned the art to exhibits in Atlanta and Baltimore.

It’s likely the painting was seen in Baltimore by a businessman and architect, Edward Joseph Gallagher Jr., a self-described “Sunday painter” who liked to collect and give art to museums. Gallagher donated the gifts in memory of his only child, Edward III, who had died in a boating accident a week before turning 14 in 1932. After his son’s death, he threw himself into his work and became increasingly interested in art.

Gallagher liked to stay at Arizona dude ranches so he had a connection to the Southwest.

He was inspired to begin donating art to the University of Arizona after reading an article in Life Magazine about “The Great Kress Giveaway,” where philanthropist Samuel H. Kress was donating his collection to museums. Gallagher began by giving French paintings and eventually would give more than 200 paintings and sculptures to the museum.

He had to persuade Jackson, the art dealer, to part with “Woman-Ochre.” Gallagher purchased it and donated it in 1958.

The painting quickly became a gem in the museum’s collection. People in the art world knew that the small Tucson museum had a de Kooning, a Jackson Pollock and a Mark Rothko.

Gallagher wanted the great works to be available to students, he told the Tucson Daily Citizen in 1974.

“I was never particularly interested in collecting for myself,” he said. “I believe art should be where everyone can see it.”

‘They stole the painting!’

The Tucson campus was quiet on Nov. 29, 1985, the day after Thanksgiving. Most of the employees and students had a four-day weekend because of the holiday.

Located just off busy Speedway Boulevard, the art museum was open that day. But it had a skeletal staff. Only two students, a security guard and Josh Goldberg, the museum’s director of education, were there.

Goldberg was supposed to have the day off. But he had agreed to meet a student and her mother who would be visiting for a school art project that morning. On his way in, he noticed a man and a woman sitting on a concrete bench outside. They sat ramrod straight, not talking to each other. The man wore a buttoned-up trench coat.

The museum opened, and the couple followed Goldberg inside.

He was in the bathroom, washing his hands a short time later, when he heard a scream. He thought the security guard may have been hurt.

He ran out, yelling, “What’s going on?”

“The painting was stolen. They stole the painting!” the guard yelled.

“Calm down,” Goldberg said. “What painting?”

“The de Kooning,” the guard said.

Goldberg looked to where “Woman-Ochre” had hung on the wall in a second-floor gallery. The painting had been cut and ripped from its backing. The wooden frame was empty, except for fragments of canvas.

The security guard ran down the stairs, and Goldberg followed. They decided to split up and circle the building, headed in opposite directions, looking for the suspects. They saw no one.

University police arrived. Distraught museum staffers hurried in. Museum Registrar Kenneth Little said he almost threw up when he saw the painting was gone.

“I feel we’ve lost a good friend,” he told a reporter for the Arizona Daily Star.

There wasn’t much of a crime scene. There were no video cameras, no fingerprints detected.

At that time, there were parking spaces and a street in front of the museum, making for a quick getaway. A witness saw a couple run and get into a rust-colored sports car. Black louvers shaded the back window. The male appeared to have something under his jacket and put it in the backseat as he got into the car. The woman drove, the car stalling and jerking as they got away.

Police believe that after the couple entered the museum, the woman chatted with the security guard to distract him. The man headed upstairs to the second floor unobserved, where he cut the de Kooning out of its frame, possibly using a box cutter. He rolled up the painting and stuck it inside his blue winter jacket. Then the couple fled.

Law enforcement circulated a composite sketch of the suspects. The woman was described as 55 to 60 years old, wearing a scarf and “granny” glasses. Her body structure was masked by bulky outer clothing. The man was described as 25 to 30 years old with curly hair, an olive complexion, neatly trimmed mustache and thick glasses.

Police alerted Phoenix Sky Harbor and Tucson international airports to look for red cars with black louvers in the parking lots. University police called car rental companies, asking if they had recently rented red cars with louvers. They were told the large car companies didn’t rent cars with louvers because of issues with damage.

The FBI was called, along with Interpol, the global network of police forces, because stolen art often crosses state and international lines.

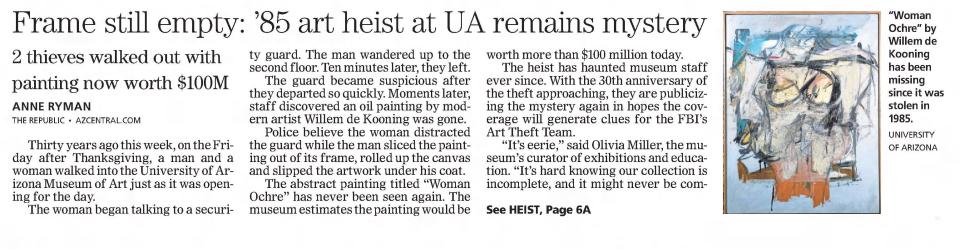

De Kooning's international reputation complicated the case. Museum Director Peter Bermingham estimated "Woman-Ochre" was worth at $500,000 when stolen, though a subsequent appraisal came in at $700,000.

The year before the theft, a de Kooning painting titled “Two Women” was auctioned for $1.9 million, the highest price paid at auction for post-World War II artwork at the time.

Corporal Brian Seastone, a young police officer, followed up on several leads.

Police reports say an anonymous male called university police and a crime hotline the day after the theft, asking if there was a reward.

He was calm, stating that the crime hotline “didn’t offer enough to have him overcome the psychological problems and counseling he would need for turning the person in for stealing the painting,” according to a police report describing the call.

He hung up and didn’t call back.

A few days later, the university announced a $10,000 reward.

A few weeks later, Tucson police arrested a man for taking seven paintings valued at $8,000 from the Western Archeological and Conservation Center. When police interviewed the man, he said he was “loaded” when he committed the theft. He claimed he didn’t have a buyer for the paintings and didn’t know what he was doing.

He laughed when police asked if he had ever been to the university. He said he didn’t even know where the campus was. Police couldn’t link him to the de Kooning theft.

The FBI worked leads, including the possibility that Santa Fe, New Mexico, was a clearinghouse for stolen art.

None of the leads panned out. The museum added a video security system the next year.

Seastone never forgot “Woman-Ochre.” He was later promoted to police chief. Whenever he learned that the FBI had recovered stolen paintings, he would follow up to see if "Woman-Ochre" was part of the lot.

“Is she in there?” he would ask.

The answer was always no.

By the time Lauren Rabb was hired as museum curator in 2009, the de Kooning theft was no longer common knowledge. Museum thefts get a lot of publicity in the beginning. When it becomes clear the artwork is not going to be easily found, people stop talking about it; it's not good public relations for future donations.

Rabb was fascinated with art crimes. She became obsessed with the de Kooning theft. She read and reread the police reports and the anonymous tips the museum had received, looking for clues.

She became convinced the upcoming 30th anniversary of the theft, in 2015, would be good timing to publicize the mystery. Stolen artwork sometimes resurfaces when people die and others inherit their belongings. The internet also wasn’t publicly available when the painting was taken in 1985. She hoped online publicity would generate clues for the FBI's Art Crime Team.

“I kind of got everyone riled up,” she said.

She left the university to take another job in mid-2013. But museum staff continued with her vision. In the second-floor gallery where “Woman-Ochre” had been stolen, they hung the painting's empty wooden frame as a reminder.

The university published a news story on its website Nov. 18, 2015, "The UA's Unsolved Case of the Stolen Painting.” At the time, I was writing about higher education, a beat I had covered for years as a reporter at The Republic. The university's release caught my eye. Who can resist an art heist mystery? So I wrote a story of my own.

‘I don’t think you guys know what you have here’

Two years later, the phone rang at Manzanita Ridge, an antiques and furniture store in Silver City, New Mexico.

On the line was Ron Roseman, the executor of his 81-year-old aunt’s estate. Rita Alter had recently died and her husband, Jerry, had passed away five years previously. Roseman was clearing out their home to put it on the market.

David Van Auker, the store’s co-owner, wasn’t interested in the estate for two reasons. The home was 30 miles away in rural Cliff. And lately, his business model had drifted away from estates and toward selling used furniture and art from upscale hotels and resorts.

Van Auker recommended Sherri Lyle, who ran an estate sale and consignment shop next door. But he said Roseman didn’t want an estate sale. He wanted the home cleared out. Roseman mentioned the home was full of high-end, midcentury modern furniture. That was enough to hook Van Auker, though he was still reluctant.

“I’ll go out and take a look,” he said.

He and his business partners, Buck Burns and Rick Johnson, headed up the winding road to Cliff on Aug. 2, 2017.

Cliff has less than 200 people. Ranch houses and mobile homes dot the rolling landscape. There is a post office, cafe, school, county fair grounds and not much else. The Alters’ home was at the top of an expansive mesa on 20 acres with views of a distant mountain range.

Van Auker thought the property was odd as their truck rolled up the long driveway and toward a pink house with red-tiled roof. Walking the yard, he spotted a stone obelisk and a pyramid covered with intricate tiles. Busts of composers, philosophers and writers, including Shakespeare and Beethoven, sat atop stone pillars. Murky water half-filled the backyard swimming pool.

Once inside the three-bedroom home, they went into work mode. They split up to do inventory, taking photographs and peeking in closets and drawers. A stone fireplace and grandfather clock dominated the living room. The furniture was dated and worn, much of it more than 50 years old.

Van Auker headed down the hall to the couple’s bedroom, where a glossy dresser caught his eye. He closed the door to get a better look at the dresser. That’s when he saw the painting.

It was a nude woman figure with a small head and large breasts. The artist had used hues of yellow, turquoise, orange, brown, green and crimson. Van Auker thought it was a print. Then he saw the cracks — small lines running across the woman’s chest and torso. This is a real painting, he thought. He assumed Jerry Alter painted it.

Van Auker liked what he saw. He thought the painting would be perfect for the guest house/vacation rental that he and Burns owned. Framed art filled their guest house. But they didn’t have any modern, expressionist pieces like this one.

“Hey, come look at this painting,” he called to Burns, who was in the next room. Burns came into the bedroom.

“I kind of like it, except for the frame,” Burns said.

A gold commercial frame held the painting.

“Do we want it for the guest house?” Van Auker asked.

“Yeah, I think so,” Burns said.

They spent another hour at the house, taking inventory and photos. Then Van Auker called Roseman and offered him $2,000 for the home’s contents plus a couple extra hundred for a few items they wanted to keep for themselves. Total cost for the painting: $200.

They returned the next morning, a Thursday, filling the backseat of a Ford F-250 truck. They wrapped the painting in a blanket and piled it atop lamps, a vase and African spears the Alters had collected during their world travels.

The painting was the first thing unloaded when they got to the store. Van Auker planned to take it home but didn’t want to leave it on the sidewalk. So they leaned the painting against a post inside the store, intending to put it back in the truck once they unloaded.

Within 20 minutes, an artist who had recently moved into an apartment across the street wandered in, looking for furniture. He asked if the painting was real. "Yes, it’s a real painting," Burns told him.

“No, is this a real de Kooning?” the artist asked, moving closer to get a better look. “I don't think you guys know what you have here. I think this is a real de Kooning.”

Van Auker and Burns brushed his comment aside. In their line of work, they saw lots of copies of famous works. They told him they would look into the painting later. They were busy unloading.

Two more customers remarked on the painting. One pointed out the exceptional brush strokes and depth of color. The artist returned twice. The second time, he offered $200,000. But he cautioned that they needed to research the painting and its value first.

During a lull in customers, Van Auker tapped “de Kooning” into his internet browser. Up popped a story on azcentral.com with the headline, “Unsolved Arizona mystery: de Kooning painting valued at $100 million missing for 30 years.”

Wow, that looks like the painting we have, he thought.

They propped the painting next to the computer screen, comparing. Every brush stroke, every drip, every swath of color was an exact match. They could see swoops in the canvas, where the painting had been cut from a frame. They could see horizontal cracks consistent with the painting being rolled and stuck under a jacket during the theft.

“We’ve got to call the museum,” Burns said.

Johnson was skeptical. He warned they would look like idiots when the painting turned out to be fake.

“It’s going to be embarrassing,” he told them.

They decided to hide the painting. Wrapping it in a blanket, Burns moved the art into the small bathroom, the only interior room in the store that locked.

Van Auker found a telephone number online for the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson. He breathed deep, and his heart raced. I’m going to sound like an idiot, he thought, as he dialed.

He told the student who answered the phone he was calling from Silver City, New Mexico. He thought he had a piece of art that was stolen from the museum. The student wanted to know what piece of art he was referring to. He told her it was the de Kooning.

“Hold please,” she said.

In her office, museum curator Olivia Miller was talking to archivist Jill McCleary. They overhead on the walkie-talkie the student explaining that a caller thought he had the stolen de Kooning to a security guard. The call was directed to Miller.

“Are we gonna remember this moment for the rest of our lives?” McCleary said to Miller.

Miller was used to getting calls from people who thought they had famous paintings that ended up being copies. Van Auker, however, said something that piqued her interest: He said the painting looked like it had been rolled up. There were little cracks across the surface.

Miller stayed calm, not wanting to portray much emotion. They exchanged phone numbers, and she asked him to email pictures. She also asked him to send her the painting’s measurements. The dimensions Van Auker sent back were off by just a couple inches, consistent with the painting being cut from its frame.

With each photo that arrived over email, they got more excited.

They called university police and the FBI.

Universities have protocols in place to handle various crises that may occur on large campuses. But there isn’t a playbook for how to return a stolen painting. University police advised museum staff not to communicate directly with Van Auker; the university needed to coordinate with the FBI and police.

Two hours passed.

In Silver City, the artist came back into the antique store, asking whether they had researched the painting. Van Auker hid his panic. He told him they were too busy; they would look into the painting’s history the next day.

At 5 p.m. they closed the store.

They weren’t sure what to do with the painting. They couldn’t leave it overnight. Someone might break in and steal it.

“Take it home,” Johnson suggested.

So Van Auker did, thus beginning a sleepless night with three guns close by.

After calling The Republic, he reread the azcentral.com story several times. The article mentioned an FBI’s Art Crime Team. I’ll call them, he thought. He went to the website but couldn’t locate a telephone number. He fired off an email instead.

That should do it, he thought, settling back on the couch and expecting a call any minute.

Hours passed. He heard nothing.

Around midnight, he called the FBI field office in Albuquerque. He felt the person who answered didn’t believe him. He pushed and got transferred to an FBI office back East. That person didn’t seem interested, either, until Van Auker told him to pull up the article on azcentral.com.

“Do you see the picture there?” he asked. “I’m staring at that painting right now. It’s in my living room.”

He said he was instructed to take the painting somewhere safe. Don’t take it back to the store. Don’t keep it at the house. The FBI will be in touch. Go to work the next day and act like nothing is amiss.

But what was about to unfold was anything but normal.

And already, so many questions had emerged. Like, how did a stolen de Kooning painting end up in the home of a retired teacher and retired speech pathologist in rural New Mexico?

The painting behind the bedroom door

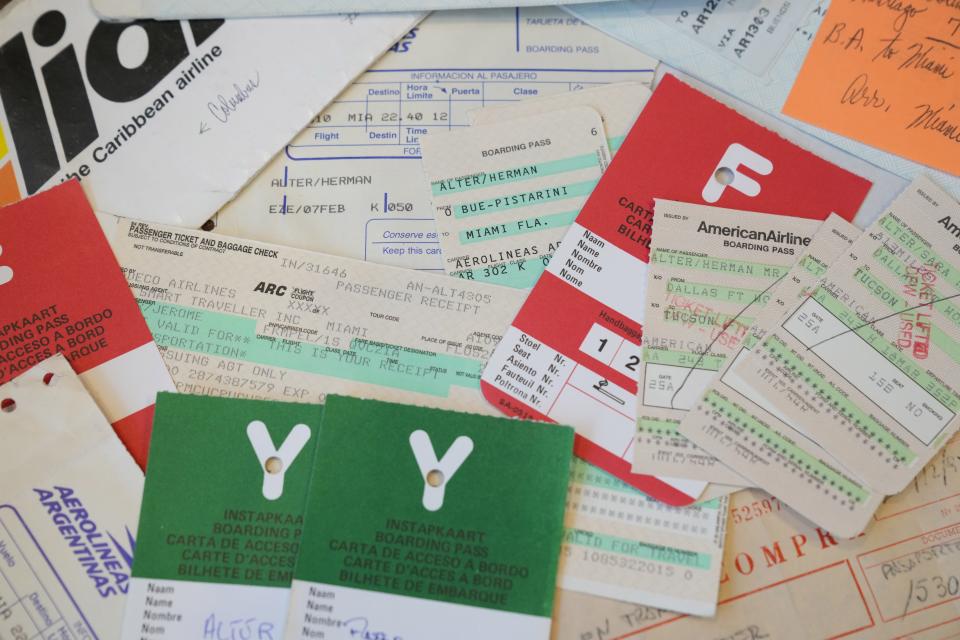

Herman Jerome and Sara Rita Alter were an elegant couple, world travelers who spent nearly every school holiday jetting off to exotic locations.

They met in the mid-1950s at a hotel in the Catskill Mountains, where Jerry Alter played clarinet in a jazz band and Rita Sinofsky had gone to be a waitress. When Rita got there, she discovered there wasn't a job opening, so she went to a cafe to mull over her predicament. That's where Jerry spotted her and struck up a conversation, according to their nephew, Ron Roseman.

They married in 1957. Jerry Alter was a professional musician and music teacher in New York City schools.

“I absolutely adored him. He was my favorite teacher,” said Claudette Laureano, who was an elementary school student of Jerry Alter’s at PS 187 in the 1960s.

He played classical music for the students and show tunes from musicals like "West Side Story." She learned to play recorder in his class. He would bring in his clarinet and play for the students.

“He played beautifully,” she said.

He would leave teaching at a relatively young age, 47, when the couple decided to “get out of the rat race,” Roseman said. They bought 20 acres in rural Cliff, New Mexico, and moved there in 1977.

The Alters lived in a trailer on the property with their two children, Joseph and Barbara, while Jerry Alter drew up blueprints and hired contractors to build a 1,724-square-foot ranch house. Rita Alter went to work as a speech pathologist for the Silver Consolidated Schools, the local school district.

They were friendly. But their worldly tastes didn’t match their surroundings. Many people in Cliff went camping for vacation; the Alters would fly off to Hong Kong, Chile, Tasmania. They had visited more than 140 countries by 2011.

Roseman said he's not sure how his aunt and uncle afforded their overseas travels on school salaries and Jerry Alter's modest retirement. He said with the exception of maybe a few years, they were never both working at the same time. He said Rita Alter inherited money when her mother died but believes that was used to purchase the Cliff property. Later on, they would have been eligible for Social Security.

"But if just doesn't fund everything they did. It doesn't even come close," he said.

Jerry Alter kept busy in retirement. Eschewing naps, he did intricate, decorative tile work outside the home. He painted, but his paintings weren’t very good. He self-published three books, but the writing wasn’t much better.

One of those books, “The Cup and The Lip,” featured what he called fictional accounts of travel adventures that “sought to maintain a connection with reality, in varying degrees.”

One story bears an eerie resemblance to the de Kooning theft. In the “Eye of the Jaguar," a grandmother and her granddaughter case a city museum and return to steal its prize exhibit, a 120-carat emerald. The thieves leave behind no clues. The jewel is kept hidden "several miles away" from the museum, behind a secret panel, "and two pairs of eyes, exclusively, are there to see" he wrote.

Like the story, "Woman-Ochre” was "hidden" behind the couple’s bedroom door, 225 miles from where it was stolen from the museum. It could only be seen from inside the room when the door was closed. Jerry and Rita Alter had the two pairs of eyes that could see it.

Neighbor Donna Impero said she also saw the de Kooning painting once but didn't recognize it as being famous or stolen. She had gone inside their bedroom to take a photo of a painting she had made for them. It depictedthe Alters riding horses on a trip to the Himalayas.

She noticed another painting behind the door, and when she asked about it, Jerry Alter told her it was a reproduction. Then "they kind of hurried me out,” she said.

The painting hung in a gold commercial frame. University of Arizona museum officials who later examined the painting said they believe the painting had only been reframed once after it was stolen — a sign perhaps that the art hadn’t passed through multiple owners.

The de Kooning appears to have been in the bedroom for some time. Van Auker, the antique dealer, said dust covered the fame. He could see an outline on the wall where the painting had hung.

In their dresser, Van Auker found an envelope marked “1985.” Inside was a picture of the Alters with a red sports car.

Witnesses told police the suspected thieves drove off in a rust-colored or cherry red sports car. The Alters almost always drove red cars, their nephew said. A handwritten note in their 1985 travel journal — the same year the painting was stolen — says they bought a red Toyota Supra earlier that year with a $3,000 down payment.

Jerry Alter died in 2012 at 81. The Alters’ two adult children were unable to serve as estate executors so their nephew took on that role.

Rita Alter seemed lost without her husband. She had always been impeccably dressed with polished red nails. Impero recalled seeing her at the post office with chipped nails and disheveled hair.

A few years later, she showed signs of dementia. She placed dozens of sticky notes inside her car to remind herself how to drive with instructions such as, "press the middle pedal to stop the car."

Her nephew and other family members made plans for round-the clock care in January 2017, so she could remain in her home. They photographed the contents. That's when Roseman saw the painting behind the bedroom door. But he said he didn’t recognize the work as being valuable or stolen.

Roseman said he later discovered a photo of his aunt and uncle spending Thanksgiving Day in 1985 with his family in Tucson. The photo places the couple in the same city where the theft took place a day later. Roseman said his aunt and uncle spent Thanksgiving with his family every two or three years. He doesn’t recall how many days they spent in Tucson that year.

A photo from the holiday gathering shows the Alters sitting side by side at the dinner table, smiling broadly. Plates of pumpkin pie are in front. Their wine glasses are full.

Neither of the Alters' two adult children were able to shed light on how their parents obtained the painting, Roseman said. He said their daughter died in 2021.

The FBI has declined comment about whether the Alters were the thieves. Tim Carpenter, senior special advisor to the FBI Art Crime Team, said the case is closed but could be reopened if new information comes to light.

"We at the FBI and Art Crime Team would love to solve this mystery just like everyone would, but we don’t have the luxury of speculation on that," he said.

He said the Alters are the only two people who know for sure how they obtained the painting and how it ended up in their house and, "they took that to the grave with them."

As for their nephew, he has no idea how they got the painting, if they were involved or if they bought it from someone. Though he doesn't want to admit it, there are a lot of coincidences that link them to the theft.

"Either they really thought it was a victimless crime or they could care less who it affected," Roseman said. "I could see it both ways. For both of them."

His uncle may have had this attitude: "People are going to be upset it was stolen — but I don’t really care, they’ll get over it — and I got what I wanted."

‘I want you to have the painting back’

Brian Seastone, who had been the officer on the de Kooning case in 1985 and was now the university’s chief of police, was awakened around 4:30 a.m. by a telephone call while on vacation in Hawaii. Early morning calls are usually not good news, he thought as he answered.

“Have you heard about the painting?” the caller said.

Oh no, not another one, Seastone thought.

“No, it’s been recovered,” the caller told him.

That same morning, Van Auker in Silver City still wasn't sure what to do with the painting.

The FBI had told him not to leave the painting at home or keep it at his store.

It was 7 a.m. on a Friday. He and Johnson, his business partner, drove around Silver City with the de Kooning wrapped in a blanket in the back seat, calling trusted friends. Nobody answered. Finally, they found a local attorney they knew who agreed to store the painting for them.

I had been out of the office the night Van Auker called me, but I picked up my voicemail. I called him back that morning. We talked at length, and he said he didn't want to go on the record until the painting was safely handed over to the university.

In Tucson, university officials were working with the FBI and attorneys on the painting exchange. An FBI agent initially suggested having the antique dealers drive the painting to Tucson. But that changed as word of the stolen painting continued to leak.

Van Auker got a call from an out-of-town attorney, who suggested he could be compensated handsomely for returning the painting. Van Auker wanted nothing to do with that. In fact, it made him angry. He had not slept. He hadn’t heard back from the university or the FBI. Frantic, he left a voicemail for the museum curator that said, in part:

“Keep this on record. I want the museum to have the painting back,” he said. “I don't want to hold it hostage. I don't want to hold it ransom. I want you to have the painting back.”

Miller, the curator, had been advised not to speak with Van Auker while the details of the painting transfer were worked out by university officials, the FBI and law enforcement. Miller and the museum's Interim Director Meg Hagyard were in and out of meetings all day.

After Van Aucker’s voicemail, Miller got permission to call him back.

Museum staff were given the green light on Friday afternoon to make the three-hour drive to Silver City. They loaded packing materials and a wooden crate into a minivan. The crate had coincidentally been used recently to transport a painting by artist Jackson Pollock, one of de Kooning’s contemporaries.

Hagyard had been in her official role only three days. She took the lead in a Dodge Caravan with Miller. Following in a Toyota 4Runner were museum Archivist Jill McCleary, Curator of Community Engagement Chelsea Farrar and Senior Exhibition Specialist Nathan Saxton.

They grabbed fast food — Taco Bell and Eegee’s — and settled in for the drive.

Hagyard drove. Miller spent much of her time on the phone, working out final details. It rained on and off, never ideal conditions for transporting art.

They arrived late Friday night, and video taken by Silver City resident Gabe Farley captured the scene as they stepped out of their cars and into the dark night.

They met the antique dealers in the front yard, exchanging greetings and hugs.

The de Kooning was inside on the floor, leaning against a wall. A small dog wagging its tail nearby and was politely ushered out. More than a dozen people crowded in, taking photos and videos. Miller knelt in front of the painting, mesmerized. She had only seen photos of "Woman-Ochre."

She nodded her head several times.

"Holy s--- balls," she said.

The expletive relieved the tension. Museum staff unboxed the simple wooden frame that had once housed the painting. It had been in storage for 31 years, awaiting this moment. Everyone marveled at how closely in size the painting matched the frame.

Van Auker and Burns took a selfie photo together. They hugged Miller, who was in tears.

Burns joked that if the painting didn't turn out to be the actual de Kooning, “Can I get it back?"

There were more photos and videos. Miller gave a brief history of the painting. Then staffers carried the painting — wrapped in a protective lining and poly foam — out into the night. Claps and cheers echoed in the darkness as they placed the de Kooning in the back of the minivan.

Miller sent an email to the FBI at 11:50 p.m.

“Everything went fine. We have the painting secured.”

“Woman-Ochre” spent the weekend inside an evidence room at the Grant County Sheriff’s Office in the vicinity of spare tires and tools. The initial plan was to have the FBI store the painting while the investigation continued. But it was decided the university museum had optimal storage conditions for the fine art.

Art moves around all the time, traveling to exhibitions or between buyers and sellers. But the de Kooning was valued at more than $100 million. Word of the valuable find was already leaking. This wouldn’t be a routine art transfer.

On Monday morning, Hagyard headed out in her minivan with the de Kooning in the back. Museum Registrar Kristen Schmidt rode shotgun. They both wore black T-shirts that said “Silver City” in turquoise letters, a way to show their appreciation to the community.

Hagyard recalled she was told not to deviate from the route back along Interstate 10. There would be one bathroom break at a rest stop. If anyone attacked the van, they should get out and flee.

She was not a fast driver. Her biggest concern was keeping up with the lead law-enforcement vehicle. A few times, other cars strayed into the convey, causing law enforcement to flash their lights to get them away.

As the convoy passed state and county lines, law enforcement from that jurisdiction would join up as escorts.

University police remained a constant presence. At one point, there was a conversation about whether they should synchronize the traffic lights to green when the convoy reached Tucson to get back to campus as fast as possible. But it was decided that could cause undue attention.

As the convoy pulled into campus, the minivan was met with the flashing lights of a police car and a video camera, documenting the historic day.

“Woman-Ochre” was home after 31 years.

‘Do you have any more of those paintings?’

Nancy Odegaard had just started working at the University of Arizona when the de Kooning was stolen in 1985.

Now, three decades later, the conservator and professor was asked to determine whether it was the one that had been stolen.

In front of eager museum staffers and a photographer, she examined the painting for about two hours. The canvas had been damaged by rolling up the painting. Tiny cracks covered the surface. The gold frame was a poor fit. She found dust and insect shells inside the frame, consistent with the painting being in a home.

She looked for signs of damage that had previously been documented before the theft. For instance, there was a puncture in the lower left-hand corner that may have been caused by a pencil in 1973.

She compared the edges of the canvas with those cut from the frame: Everything matched.

Was the painting the real “Woman-Ochre?”

“I think we’re all in agreement,” she said to an emotional museum staff.

The long-lost painting was national news. University officials feted the antique store owners as heroes at a news conference on the Tucson campus. So many years had passed, no one quite remembered the details of the $10,000 reward. The antique store owners said they wouldn’t accept one anyway.

The painting remained on campus as FBI evidence for more than a year. A university committee formed to discuss how to repair the extensive damage so "Woman-Ochre" could be put on exhibit.

The world-renowned J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles agreed to undertake the research and conservation project at no cost to the university in exchange for being allowed to exhibit the work for a few months. Tom Learner, head of science at the Getty Conservation Institute, oversaw the conservation project along with Ulrich Birkmaier, the senior conservator of paintings at the Getty Museum.

Among the Getty's findings:

De Kooning used house paints, mixed with oil paints, on "Woman-Ochre." For instance, the drips above and below his signature are house paints.

Two coats of discolored varnish had to be removed, including a cheap varnish applied by the thieves.

The painting was cut out and ripped from its backing during the theft. This caused tiny cracks and paint loss. Conservators had to reattach lifting and flaking paint using special tools and a microscope.

Conservators used a tiny brush and pigments to fill in areas where paint had been lost, known as "inpainting."

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed conservation work, which took nearly three years. The Getty is displaying the painting from June 7 to Aug. 28 before the painting returns to the university art museum for exhibit beginning Oct. 8.

The painting’s long journey has been a once-in-a-lifetime experience for many people involved.

On a recent day, Van Auker reflected on how "Woman-Ochre" has changed his life during an interview inside his Silver City store.

“I still think of it as ‘my painting,’” he said as he settled back on a used sofa. He was dressed in his usual work clothes: T-shirt, baseball cap, cargo pants and hiking shoes. An antique clock behind him chimed the hour.

At least once a week, someone will ask about the stolen painting. Customers joke, “Do you have any more of those paintings?” Van Auker never tires of telling the story. It’s the most exciting thing that has ever happened to him. He has been interviewed more times than he can count. People have called the store, just to say, thank you.

“There is no amount of money that I would take to give up this experience. None,” he said. “This was worth millions to me.”

The university gave him the gold frame that once housed the de Kooning after it was stolen. Van Auker proudly hung the empty frame in his guest house.

There are times when he will be doing a mundane chore, like cleaning up dog poop in the yard, and he will get a grin on his face as he thinks:

And I’m the one who found the de Kooning!

Reporter Anne Ryman was the first journalist to break the story that "Woman-Ochre" had been recovered. She has written extensively about the de Kooning painting. Have a question about the painting? You can reach her at anne.ryman@arizonarepublic.com or 602-444-8072. Follow her on Twitter @anneryman.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Saga of Arizona's stolen Willem de Kooning painting 'Woman-Ochre'