What Sam Bankman-Fried’s Defense Said in Its Final Chance to Save Him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Slate’s daily coverage of the intricacies and intrigues of the Sam Bankman-Fried trial, from the consequential to the absurd. Sign up for the Slatest to get our latest updates on the trial and the state of the tech industry—and the rest of the day’s top stories—and support our work when you join Slate Plus.

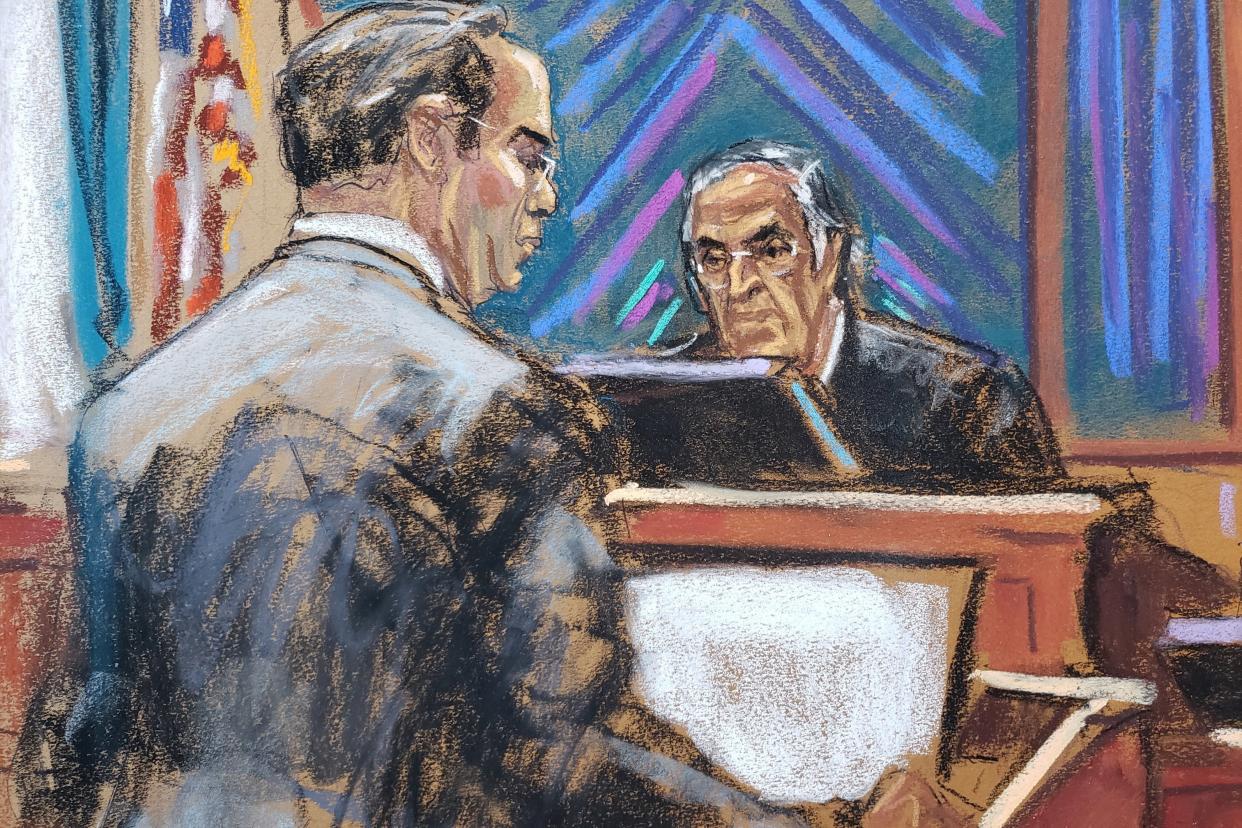

Folks, we’re nearing the end of United States v. Samuel Bankman-Fried. Last I checked in, we’d come off a brutal cross-examination of the defendant that ran well into Monday evening. The next day, Assistant U.S. Attorney Danielle Sassoon completed her interrogation, and Bankman-Fried’s defense rested after lobbing a few more questions at its client. The rest of Tuesday saw attorneys working out details of the seven charges, preparing everyone for the moment when all parties would make their closing arguments.

The prosecution went in swinging on Wednesday morning, with Assistant U.S. Attorney Nicolas Roos addressing the jury. The government ended as it began, nearly a month ago: with a muscular argument that was tightly organized and unrelentingly damning.

Drawing on exhibits and excerpts of testimony from the trial, Roos described a “pyramid of deceit built on a foundation of lies and false promises.” SBF, in Roos’ telling, was just in it for the money—and despite all the crypto jargon, what he did to get it was commit some old-fashioned crimes. Theft, lies, deception, greed: SBF knew he was stealing customer funds from FTX and that it was wrong, Roos said, yet did it anyway, figuring he could “talk his way out of it.” Even during his testimony in the trial, this trait was on display: When the defense asked Bankman-Fried about things that “didn’t really matter,” like the defendant’s pre-Alameda employment, his testimony was “smooth,” and he willingly defined about “50 terms.” When Sassoon questioned him, though, the defendant turned into a “different person” who, suspiciously, couldn’t remember a “single thing”—he never said “I don’t recall” to his own counsel, Roos pointed out, but he offered that phrase as an answer about 140 times in the cross-examination, even after Sassoon asked him about terminology he’d already defined.

Roos raised three questions: Where did all of the FTX exchange’s billions of dollars in customer deposits go? What happened? And who is responsible? Well, “the evidence shows” that SBF stole money from customers who trusted him. Roos pointed to a bit of former Alameda Research CEO Caroline Ellison’s testimony, in which she claimed that SBF saw FTX customers as a “good source of capital” and set up the system that allowed Alameda “to borrow from FTX”—i.e., to funnel customer deposits directly into his hands. He set this up through a “secret system,” as explained by Ellison, Gary Wang, and Nishad Singh from the stand: SBF granted Alameda, the crypto hedge fund he’d co-founded, an account on FTX with “special privileges” not afforded to the exchange’s other customers, including the encoded ability to hold a negative balance on FTX without triggering automatic liquidation (a task “suggested” by SBF and carried out by Wang and Singh), as well as the ability to draw on an essentially unlimited line of credit with FTX sans collateral. Despite this, SBF continued to say in public, to whoever listened (customers, Congress, investors), that money stored with FTX stayed on the platform, that there were “no conflicts of interest” in his co-ownership of FTX and Alameda, and that customer assets were sufficiently protected.

Pulling up even more exhibits, the prosecutor showed that Bankman-Fried’s signatures, both digital and physical, were basically everywhere: on the sheet establishing Alameda’s “North Dimension” account with Silvergate Bank (RIP); in the tweets affirming that Alameda’s FTX account was treated “just like everyone else’s” (oops); in the Google metadata from a June 2022 balance sheet demonstrating that Bankman-Fried was aware that Alameda had by then borrowed $10 billion from FTX customers (eep!); in the Google metadata on a September 2022 sheet showing that SBF was also aware that Alameda had by then borrowed nearly $14 billion from FTX (Mamma mia!); in the Google metadata on yet another September 2022 doc listing lines of credit on various FTX accounts, including Alameda’s (proving, Roos said, that SBF’s statements on the relationship of FTX to Alameda were “public lies” that “show criminal intent”).

The assistant U.S. attorney then laid out “six points” where SBF could have taken a different path but instead chose a dastardly one: 1) using customer money to buy back Binance’s $2 billion FTX stake in 2021, since FTX had only $1 billion in revenue and Ellison had notified Bankman-Fried that drawing from customers would be necessary for the task; 2) splurging billions on new investments in late 2021 using customer deposits, which he knew because he’d seen a balance sheet (“because everyone loves spreadsheets,” quipped Roos) from Ellison recording that Alameda had “more loans than it had assets”; 3) paying back Alameda loans in June 2022, despite his demonstrable awareness of billions still owed to FTX customers; 4) working with Ellison that month to craft and disseminate Alameda balance sheets that would pass muster with investors like Genesis and BlockFi, both of which then granted new loans to a hedge fund much more rickety than either had realized, as former BlockFi CEO Zac Prince testified; 5) learning that Alameda now owed a $13.7 billion debt to FTX and still approving the withdrawal of hundreds of millions in customer funds for venture investments; 6) publishing “false tweets” during the November collapse about how FTX had enough to cover all client holdings even while acknowledging privately that the company had maybe enough to reimburse a third of them.

At any point, Roos said, SBF could have taken a different route—he could have come clean about the business troubles and avoided cocking a multibillion-dollar Chekhov’s gun by “stealing” even more customer and investor money. Instead, Roos said, he stole even more customer and investor money along the way.

So, what happened? “The defendant was motivated by greed and ambition.” Where did the money go? “To investments, to purchases, to expenses, to donations.” Who was responsible? “The defendant.” After the lunch break, Roos then went over the seven charges Bankman-Fried is facing, along with the bits of evidence he said backed them up. (As a reminder: wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud on FTX customers, conspiracy to commit commodities fraud on FTX customers, conspiracy to commit securities fraud on FTX investors, wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud on Alameda Research lenders, and conspiracy to commit money laundering.)

Roos closed out his presentation by preempting three lines of argument from the defense: SBF’s “good faith,” belied by the auto-deletion function on important Signal chats and the “coded language” (e.g., “the thing”) used to discuss potentially illegal matters; the “Thought It Would All Work Out” stance, in which SBF blamed others for losing the money, even though the theft itself was the crime; and the “margin lending” defense that got “more and more absurd” as the trial went on—look at the customers, like the case’s very first witness, who couldn’t recover their FTX accounts even though they’d never opted in to its spot margin–trading program, which hadn’t even been responsible for the most withdrawals from FTX. (That would be Alameda, whose account, notably, was also not part of the spot margin program.) SBF, Roos said, just “wanted more money to do whatever he wanted with.”

SBF’s lead counsel, Mark Cohen, then offered a closing statement that was nowhere near as protracted, well assembled, or aggressive but was certainly no less passionate. After thanking the jury for their “service,” Cohen, deploying the soft voice with which he’d delivered his opening statement, characterized the whole thing as a mismatch of two very different cases. The government “spent an extraordinary amount of time” essentially staging a “movie” in which Sam Bankman-Fried was the “villain”—a characterization that was “simply not true and, more importantly, is not a basis on which to decide this case.” The case against his client depended on “paint[ing] Sam as a monster,” by showing photos of him hanging out with celebrities and talking about his “sex life” (referring, of course, to Caroline Ellison) instead of litigating the facts. The prosecution also didn’t focus on the fact that Bankman-Fried built a “successful business” that “grew exponentially” from 2019 through 2022, but instead characterized “differences in business judgment” as something much more nefarious. There were mistakes: “FTX did not have a successful risk-management infrastructure.” But that’s “not a crime.”

Cohen then went through some legal points that, he claimed, applied “to all charges.” SBF didn’t have to testify, but he wanted to tell his story to the jury and did a very hard thing—and the government was unfair to characterize his spiels as “evasive,” though they were admittedly “far from polished”: “He was himself. He was Sam. … Why would he do that just to lie?” If he couldn’t remember everything, well, no one could recall all that, honestly, especially after “speaking with something like 50 journalists” after the FTX collapse while relying on memory. That applied even to congressional testimony—why would a criminal mastermind opt to lie on Capitol Hill? The government wanted to make like FTX was criminal stuff from the beginning, but it was in fact established to drive “innovations” in the crypto industry, offering services like crypto-deposit-pooling wallets and margin trades that weren’t available elsewhere. “Nothing wrong with that,” he said, echoing his opening statement again. The North Dimension thing, by the way, was no secret; it was right there on the FTX site! (There was no mention of Alameda in the screenshot then displayed to the court, for what it’s worth.) As for the Bahamian luxuries like the penthouse and the private plane? “Reasonable business expenses.” The political donations, “which are some of the most regulated publicized and scrutinized forms of spending” in existence … why would anyone steal to carry those out? (There was no mention of the dark-money factor.) And anyway, FTX had a “multibillion-dollar valuation” (no mention, naturally, of the reported misrepresentations that led to said valuation—or how quickly said valuation plunged in November 2022) that made it clear it had enough liquidity to do the things it wanted.

Cohen harped on a point to which he’d frequently alluded throughout the trial—that the former FTX and Alameda employees who testified on the stand had the benefit of special government deals, whether through pleas, immunity, or nonprosecution agreements, and they had occasional inconsistencies in their accounts as well as repetitive points among their statements (a funny point in light of Cohen’s excuses for SBF). Further, “none of the witnesses testified that Sam told them to violate the law” (… maybe not in those exact words). Cohen then cast doubt on other witnesses. The first guy, the commodities trader who’d lost money on FTX—why would he start an account there after viewing an ad featuring Gisele Bündchen, whose last name he said he didn’t even remember? Another customer who’d said he’d never read FTX’s terms of service but trusted Bankman-Fried based on his tweets—why would anyone do that? The professor who traced the money outflows from Alameda and FTX—did he ever ask why Bankman-Fried would make those splurges?

Most confusingly, Cohen stated that the government was focusing on alleged misdeeds from a timeline of June through November 2022, ignoring the moments from 2021 (the Binance buyout, the late-year Alameda calculations and investments) mentioned earlier that same day. (OK?) Most hilariously, both prosecution and defense ended up accusing each other of focusing too much on the FTX-branded Miami Heat arena for their cynical, individual purposes.

And that was it: “Nothing wrong with that.” On to Thursday, when we’ll probably get a prosecutorial rebuttal. And then it’s in the jury’s hands.