Sam Bankman-Fried’s Bid to Get an Effective Altruist in Congress Is Even Sketchier Than Anyone Realized

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The trial of Sam Bankman-Fried was pitched by close observers as something of a reckoning: for the cryptocurrency industry, for the Silicon Valley move-fast-and-break-things ethos, for the freewheeling zero-interest-rate era, and more generally for the blind spots of American capitalism. But it also lowered an unforgiving microscope on effective altruism, the utilitarian philanthropic movement to which the disgraced FTX CEO subscribed. For, despite their ostensibly laudable intentions—earning heaps of money and giving it away to charities and nonprofits that address major issues like global poverty and public health—effective altruists appear to have been willing and enthusiastic participants in some of the man’s sketchiest schemes.

Even though SBF’s first trial is over, the aftermath of the 2022 FTX collapse is still unfolding: The crypto exchange’s bankruptcy estate continues to claw back the billions of dollars misappropriated by its former CEO; political movements and institutions supported by SBF have either perished or persisted in zombie form, like a pandemic-preparedness referendum in California; and the onetime crypto king faces civil charges as well as another potential federal trial in March over five more criminal charges. As crypto analyst Molly White put it, there are plenty of “unturned stones” in the SBF story.

The vast troves of evidence released to the public during the trial made apparent that some of these stones relate to one of SBF’s more peculiar and revealing ventures: the time he and his network spent a fortune to try to elect an EA-minded congressman in Oregon.

The early-2022 Democratic contest in Oregon’s 6th Congressional District was, notoriously, one of the most expensive races in that year’s midterms cycle by a staggering amount: Carrick Flynn’s losing primary campaign earned about $12.24 million, which alone is almost double the amount that the Democratic and Republican primary winners earned in total for their general-election campaigns. Previously unreported and unexamined details unearthed from the trial exhibits, and from conversations with Oregonians who observed the primary, show the extent to which SBF and his fellow EAs coordinated their efforts to get one of their own into a seat of power. It was covered primarily as a crypto story at the time, but it’s really an EA story—about how, for all their high-minded rhetoric about using their earnings to save lives and better humanity’s future, they often ended up just circulating their funds among themselves.

Here’s the tale we previously knew: In February 2022, when the Democratic primary for Oregon’s newly drawn 6th District was already well underway, a 35-year-old pandemic and A.I. policy specialist named Carrick Flynn suddenly shook up the race by announcing his candidacy. (He did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this piece.) Although Flynn had grown up in the state and attended the University of Oregon as an undergraduate, his campaign almost immediately elicited suspicion within the district, which encompasses some of the state’s most populous and liberal areas (Salem, the Portland suburbs). To start, the regions where Flynn grew up and attended college lie in the 1st and 4th districts, respectively. Beyond that, Flynn had been a nonpresence in Oregon, much less local politics, since his graduation.

Flynn had spent much of his career abroad, taking on admirable social-service projects in Africa and Asia. He was also an affiliate of the Centre for the Governance of AI, which was established in 2018 as a subsidiary of Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute—an incubator for effective altruism and “longtermism” headed by Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom. Flynn’s campaign benefited from millions and millions of dollars spent on his behalf, unprecedented for any House district primary, even though just 2.5 percent of his donations came from 6th District residents. The vast majority of Flynn’s backing came from figures and political action committees linked to Sam Bankman-Fried.

Throughout the race, as local and national journalists zoomed in on some of those connections, Flynn and his campaign constantly denied that he knew SBF, had any direct ties to SBF, or was being supported by SBF for any reasons that were not altruistic in nature. This was despite the fact that both of them had embedded within the same EA circles for years, sharing mutual acquaintances and business partners like Nick Beckstead and Andrew Snyder-Beattie, two FHI alumni who’ve since worked with the EA-boosting Open Philanthropy Project nonprofit. (Neither of them responded to multiple requests for comment.) So what if effective altruists were pouring a total of $11 million into his race for a district Flynn was hardly familiar with? The campaign’s line was that this was simply a result of Flynn’s political prowess, and of his dedication to EA priorities like pandemic prevention (and nothing, notably, to do with cryptocurrency).

In short, Flynn was a white man barging into this race as an outsider, amply backed by a network of other outsiders, in order to overtake a well-known front-runner: Andrea Salinas, who’d previously served as a state representative and was shooting to make history as Oregon Democrats’ first Latina member of Congress. (Salinas’ office declined a request for an interview.) All around, the optics were not great, which is likely why Flynn lost the primary vote to Salinas by 18 points, even though he’d out-earned and outspent the eventual winner by a mile and a half. Afterward, Flynn supported Salinas in the general election and disappeared from the digital sphere following her victory—which happened to coincide with the fall of Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto empire.

The story Flynn liked to tell of how he got involved in politics is that, as the COVID-19 pandemic walloped the U.S., he linked up with his former FHI colleague Snyder-Beattie, who’d become a program officer at Open Philanthropy (a nonprofit co-founded by three fervent EAs, including Facebook’s Dustin Moskovitz, that once provided a generous grant to launch Georgetown University’s EA-aligned Center for Security and Emerging Technology—where Flynn was then working as a research fellow). Flynn and Snyder-Beattie formed a policy team that came up with pandemic-prevention recommendations for the Biden administration and for Congress, although none of it was ultimately adopted. Flynn later told reporters for Vox’s EA-funded Future Perfect vertical that by late 2021, “a lot of people suggested I should run” for office:

It actually wasn’t my idea. I’d moved back to Oregon because I could work from home, and I didn’t want to keep living in D.C. Then a new congressional district [the 6th District] kind of opened up under me. And all sorts of people from all different areas of my life were like, “You have to run. You have to run. You have to run.” And I’m not a politician. But enough people said it to me that I started asking other people, people who I really respect, if this is something I should consider. A lot of these people are very into effective altruism reasoning.

“Very into effective altruism reasoning” is certainly one way of describing them.

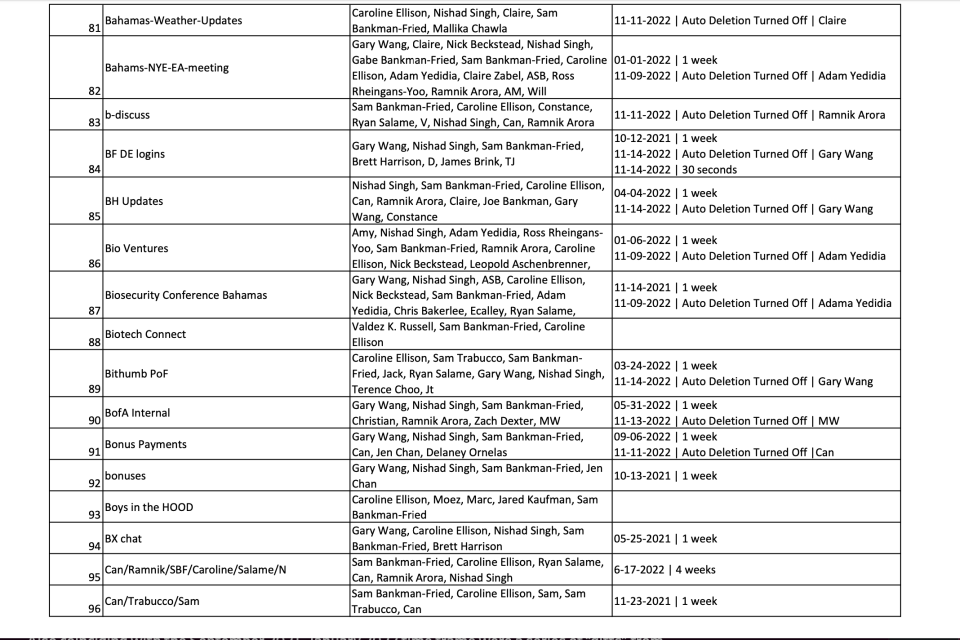

Around the same time, Snyder-Beattie was communicating with Sam Bankman-Fried and others at FTX and Alameda in several Signal group chats, as revealed in a table presented as evidence during the SBF trial:

To be clear, the contents of these chats were not released during SBF’s trial, so we have no further insight into what was discussed. Yet it’s notable that the timeline of these chats and participants coincides with the buildout of EA political infrastructure. First came the establishment of Gabe Bankman-Fried’s Guarding Against Pandemics PAC, announced on the official Effective Altruism Forum Sept. 18, 2021. The next day, it received a $5,000 donation from Michael Sadowsky, a former colleague of Gabe’s at the political data firm Civis Analytics. (That November, Sadowsky’s People for a Progressive Governance outfit got $500,000 from Singh; Sadowsky did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) On Nov. 1, 2021, Beckstead left Open Philanthropy to become CEO of FTX’s own philanthropic arm, the FTX Foundation; shortly after Christmas, his former employer’s parent company, the Silicon Valley Community Foundation Donor Advised Fund, would receive a “tax deductible” and “flexible” donation from FTX’s Singh that amounted to an overwhelming $10 million.

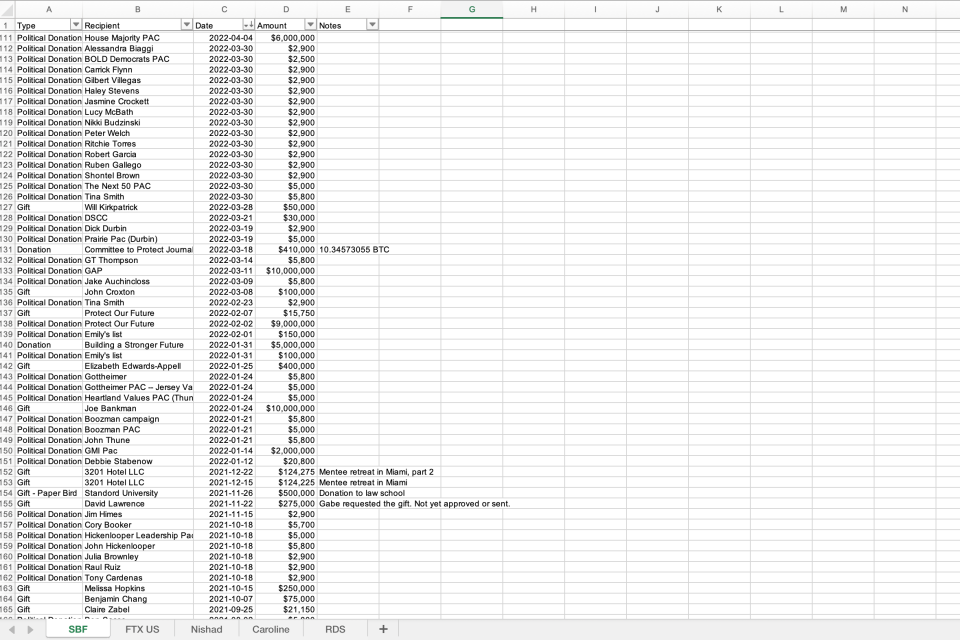

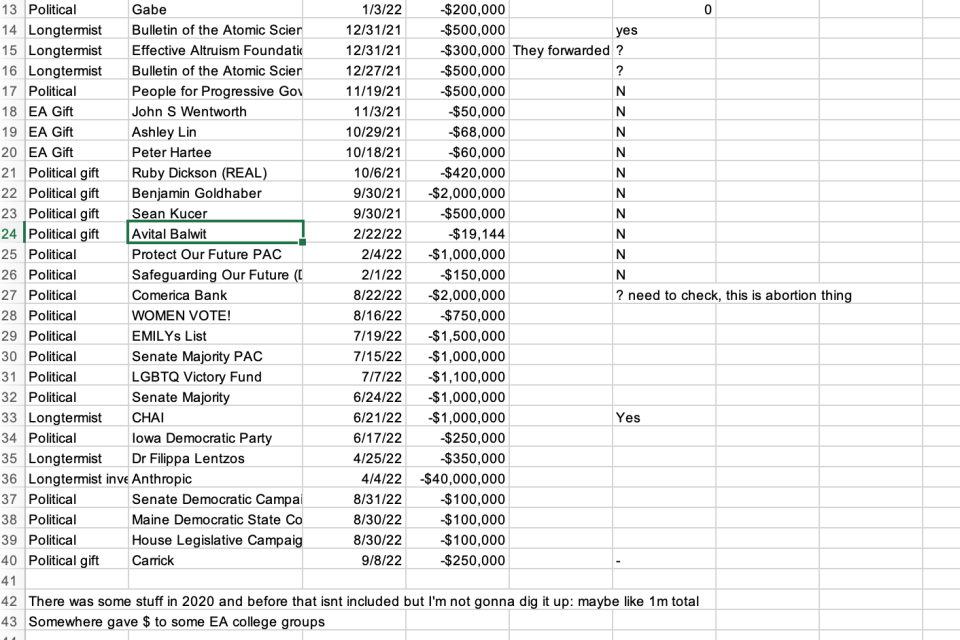

Also coinciding with the September 2021–January 2022 time frame were a series of “gifts” from SBF and Singh to EA supporters like Zabel ($21,250), Melissa Hopkins ($250,000), Ashley Lin ($68,000), and SBF’s brother Gabe ($200,000). These transactions were recorded on an FTX-internal spreadsheet exhibited at the SBF trial during Singh’s testimony—during which he admitted that Alameda money (read: FTX customer deposits) wired into his Prime Trust bank account was often disbursed by others under his name.

Beginning on Jan. 6, 2022—almost two weeks before Flynn’s Federal Election Commission registration to run on Jan. 19—a whole bunch of EAs not only began spending on Flynn, but in some cases maxed out their donations from the jump. Between Jan. 6 and 19, Flynn’s campaign received such donations from Zabel and Hopkins, who had just received “gifts” from SBF and Singh, as well as donations from Claire Watanabe, Sadowsky, Snyder-Beattie, and Andrea Lincoln (the girlfriend of FTX’s Adam Yedidia, who later testified against SBF during his trial). Various other employees of Alvea, Open Philanthropy, and the EA-supported Redwood Research firm threw in for Flynn as well, along with staffers from the rival A.I. firms Anthropic and OpenAI—the latter of whose board of directors included EA researcher Helen Toner, who’d collaborated with Flynn as his colleague at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

Carrick Flynn’s campaign received more than $450,000 from individual donors before it had even registered or he’d made a public announcement. According to FEC filings, the only Oregonian who’d donated to Flynn during that January time span was a family member. Snyder-Beattie himself only made an appeal to other like-minded folks to donate to Flynn on Feb. 5, in a post to the EA Forum published a few days after Flynn’s public campaign announcement. (That post seems to have successfully netted Flynn a few dozen small-dollar ActBlue donations.)

It gets even weirder when you look at how the money flowed after Flynn’s public February announcement. Some of Flynn’s donors received “gifts” from SBF & Co. after their donations, according to a spreadsheet released in the trial. For example: Will Kirkpatrick, a corporate sustainability adviser from the U.K., maxed out to Flynn on Feb. 4, then received $50,000 from SBF on March 28 as a “gift.” Elizabeth Edwards-Appell, an EA enthusiast who formerly served in the New Hampshire Statehouse, gave $5,800 to Flynn on Jan. 14, then got $400,000 from SBF near the end of the month. Speaking of SBF: On March 30, the Bankman-Fried brothers donated $5,000 each to the Next 50 PAC—which in turn dispatched $5,000 to Flynn’s campaign and another $5,000 to Guarding Against Pandemics the very next day.

More funding strangeness revolved around Flynn’s mysterious campaign manager, Portland native Avital Z. Balwit, who did not respond to multiple requests for comment. During her senior year at the University of Virginia, Balwit worked as a legislative intern for Sen. Ron Wyden and earned a Rhodes scholarship, which granted her the opportunity to study philosophy at Oxford University in 2021. In a Facebook post that April, Balwit announced that she’d be “living in Oxford for the next 2.5+ years,” working first as a research scholar at FHI before beginning philosophy studies in the fall. But she did not stay in Oxford for two and a half years: Per a December 2021 post on her now-deleted Twitter account, Balwit returned to Portland by the end of the year, ultimately forgoing the Rhodes grant. On Jan. 31, 2022, according to FEC records, she earned her first salary disbursement as a staffer for Carrick Flynn’s congressional campaign, which had officially registered with the FEC just a week earlier. On Feb. 1, she piggybacked off the Flynn campaign launch video to declare she’d “left Oxford to run Carrick’s campaign” and was “honored to work for him!” (Her only prior campaign experience had been a high school internship with Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber’s successful 2014 reelection effort.)

According to FEC records, Balwit was the only person to have received any monetary compensation from Flynn’s campaign. Per an FTX-internal Excel spreadsheet exhibited during the SBF trial, Balwit was also sent a “political gift” of $19,144 from FTX’s Nishad Singh on Feb. 22, 2022—an amount that was never reported to the FEC despite its supposedly “political” intent. In March, Balwit joined the four-judge panel for an official “blog contest” co-sponsored by the FTX Foundation’s Future Fund. The first round of the competition disbursed $100,000 prizes to the creators of five newish blogs that engaged with EA concepts. One of the eventual winners? Balwit’s own sister, Xander. On the archived webpage announcing the contest, Balwit’s role in Flynn’s campaign warranted no mention; her formal affiliation was instead listed with FHI, even though she was no longer at Oxford. And yet, a few months later, she told outlets like the Oregonian and Salon that “we haven’t had any conversations with” Flynn’s biggest backers, and that “while it appears that [SBF] does do advocacy around crypto, his primary focus is an advocacy project around pandemics.”

What else was weird about Flynn’s campaign? Plenty, if you talk to the Oregonian politicos who were there when it all unfolded. “On his FEC filing paperwork, Carrick listed a house in McMinnville as his campaign HQ,” primary rival Matt West tweeted. “When my team dug into Sam and Carrick’s connections, we noticed that the house was rented out about six weeks before Carrick launched his campaign.” This was confirmed at the time by local papers like the Oregonian and the Salem Statesman Journal, which noted that from September 2020 onward, Flynn had stayed with family members in the town of Aloha (which lies in the 1st District) “before renting and moving into a house in McMinnville in November 2021.”

West, who’d lived in and around the 6th District for almost a decade after moving to Oregon to work as an engineer at Intel, told me later in a phone conversation that “we were not aware of anybody [in local politics] who was working with or supporting Carrick Flynn. He genuinely seemed to come out of nowhere and just have a bunch of money.” Further, the concentration of crypto efforts behind Flynn’s candidacy struck local observers as odd, not least because West himself had direct experience in the crypto industry, as a former developer for the blockchain protocol Yearn.finance. Oregon state Rep. Mark Gamba, a peer of West’s who’d previously made a 2020 bid for the U.S. Congress, said to me, “It was a little surprising, if that kind of money was going to come out of the crypto industry, that West wasn’t getting at least a significant portion of that.” The only conclusion Gamba could derive was that it was less a crypto-focused campaign than it was “a pretty focused effort to get a particular individual elected.” He added that Flynn, early in his campaign, “reached out and asked for a conversation. I told him I was willing to meet with him but that I had already endorsed Matt. So it never happened.”

Doyle Canning, a longtime progressive activist who currently chairs the Oregon Democratic Party’s Environmental Caucus, also got a taste of the EA campaign’s spillover effects from her perch as a primary candidate for Oregon’s 4th Congressional District, a race she lost to current U.S. Rep. Val Hoyle. “With Flynn’s campaign, there was definitely a sense among Democratic activists and politicians of, like, Who are these people?” Canning told me in a phone conversation. She and others had pinpointed spending in their district from GMI PAC, the pro-crypto lobbying firm headed by Anthony Scaramucci that also received millions of dollars in donations from SBF, Ryan Salame, and Gabe Bankman-Fried.

Such vast sums of money going into such small races—it was bizarre enough to capture national attention, but it was local enough for Oregonians to understand why their state had become a lab for free-flowing money, as its local campaign finance regulations are looser than other states’. The irony was especially pronounced with Flynn’s strongest opponent, Andrea Salinas, being a loud supporter of campaign finance reform. Yet Flynn’s financial backing allowed him to blanket the area with TV, digital, and radio ads, making for a campaign so inescapable that, Canning told me, she came upon constant Flynn promos in the 4th: “We saw ads even here! It was like they ran out of TV to buy.”

For his part, West thinks the spending glut “backfired” for Flynn’s boosters, not least because it brought all sorts of negative attention to the outsider: “There were tons and tons of comments on social media making fun of Flynn’s ads nonstop because you could not go on YouTube or Instagram without seeing at least two different Carrick Flynn ads within the same ad break.” Two different Twitter accounts, @HenryPicklesPDX and @Carrick_Flynn, popped up solely to poke fun at the candidate. The latter went even further by tweeting out a screenshot characterized as a smoking gun: SBF himself “liking” Flynn’s 2018 marriage announcement on Facebook. I dug up that Facebook post and could not find an SBF like there—yes, he still has an account—but that doesn’t rule out the possibility that he could have removed his like after the fact. Notably, another person who “liked” that Facebook post was Nick Beckstead.

The Flynn campaign may have raised a lot of outside money—to the tune of $11 million—but it also raised a lot of suspicions. There was the Feb. 4 release of a pro-Flynn ad from Protect Our Future—the super PAC headed by Michael Sadowsky and funded largely by SBF—that used footage from a Flynn campaign ad that hadn’t been made public at that point. (Flynn’s campaign “was filming hundreds and thousands of dollars of b-roll, which is unheard of,” as such footage is usually intended for super PAC use, West told me; Flynn’s campaign denied any coordination with POF to Willamette Week.) And there was the House Majority PAC’s reception of a $6 million donation from SBF on April 6, and its subsequent spend of $1 million on pro-Flynn campaign ads—an unprecedented move for a national Democratic Party institution. “It’s always a surprise for us,” Avital Balwit told local media in response. As West later tweeted, this seemed to represent an effort from national Dems to curry favor with SBF, who’d already been a record fundraiser for the party and had planned to spend even more come 2024: “Nobody wanted to go up against $15 million of spending, especially when Sam was saying he would spend $1 billion.”

After Flynn’s campaign lost, Balwit went on to join the FTX Future Fund full time in June, becoming part of a team that had grown under Beckstead’s leadership, with Will MacAskill, Yale Law professor Ketan Ramakrishnan, and FHI alum Leopold Aschenbrenner having all joined on Feb. 1. (Aschenbrenner, who did not respond to multiple requests for comment, had also worked at the Forethought Foundation, a MacAskill-founded EA org that was party to the $10 million donation Nishad Singh had given to the Silicon Valley Foundation Donor Advised Fund in December. He now works for Ilya Sutskever’s “superalignment” team at OpenAI.)

🚨 JUST IN —

The entire team behind the FTX Future Fund, the Sam Bankman-Fried philanthropy, has resigned.

A holy-shit moment in the world of effective altruism. pic.twitter.com/5YY886OdNh— Teddy Schleifer (@teddyschleifer) November 11, 2022

Balwit would be the last Future Fund hire before FTX collapsed in November—after which all fund advisers formally resigned, claiming in a statement that they “have fundamental questions about the legitimacy and integrity of the business operations that were funding the FTX Foundation and the Future Fund,” that they “condemn” the “extent that the leadership of FTX may have engaged in deception or dishonesty,” and that their “hearts go out to the thousands of FTX customers whose finances may have been jeopardized or destroyed.”

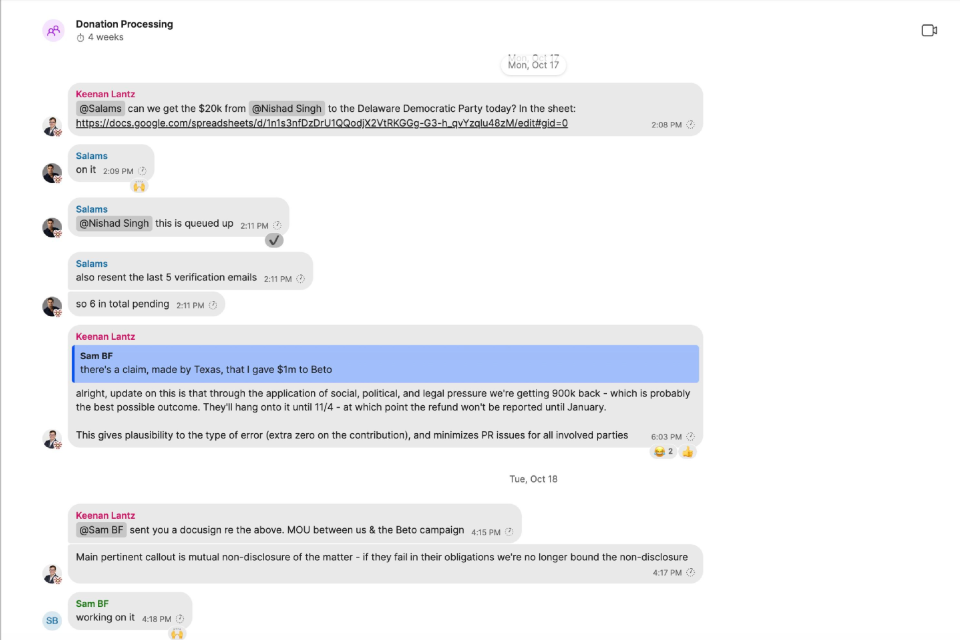

According to court documents, Balwit herself ended up joining many SBF-led Signal group chats: “FTX Foundation Funding,” “EA Discussion,” “FTX Foundation + GAP Chatter,” and, most importantly, “Donation Processing,” to which Beckstead added Balwit in September 2022. It’s unclear whether the latter had anything to do with the Future Fund, considering that neither Ramakrishnan nor Aschenbrenner appears to have been a member of that chat. What we do know, thanks to the trial, is that “Donation Processing” was at the very least a key instrument for SBF & Co.’s straw-donation schemes—screenshots introduced as evidence show how Guarding Against Pandemics employees like Michael Sadowsky, Gabe Bankman-Fried, and Keenan Lantz all worked with SBF and Singh, among others at FTX, to coordinate donations to particular organizations under one another’s names.

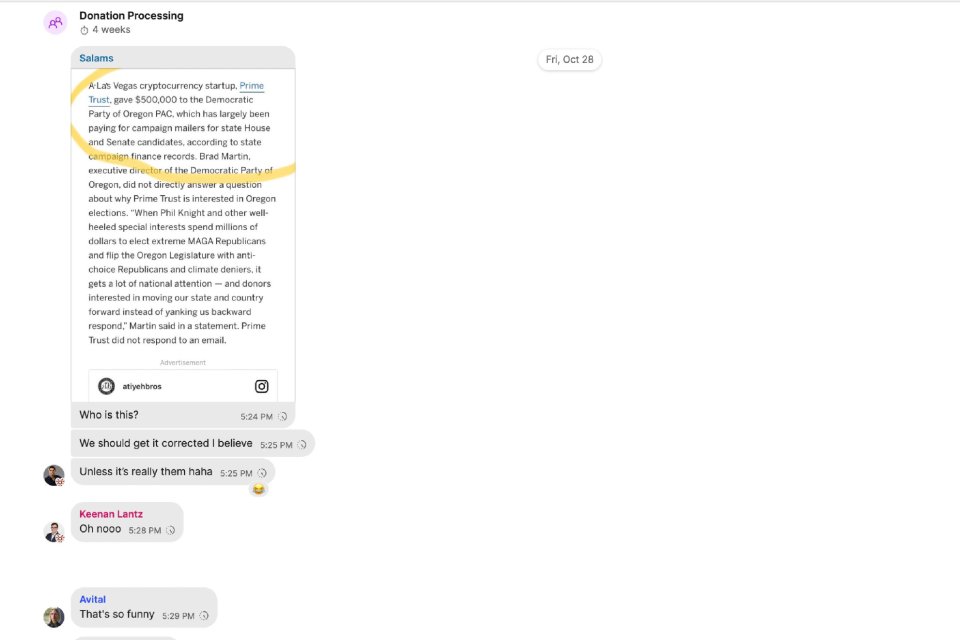

It may seem odd that Balwit would join forces with the very people she said were not involved with the political campaign she’d managed, but here’s something weirder. On Oct. 28, 2022, according to the messages exhibited in the SBF trial, FTX exec Ryan Salame sent “Donation Processing” a screenshot of an Oregonian article that initially credited a recent $500,000 donation to the Democratic Party of Oregon PAC to a “Las Vegas cryptocurrency startup called Prime Trust.” Salame insisted on the need to have it “corrected,” which Lantz said should fall to Singh; in response, Balwit texted, “That’s so funny.”

It appears what happened is that Singh, in October 2022, had tried to broker the donation to Oregon Dems through a consultant for Balwit’s old boss Ron Wyden. Thanks to Singh’s own obfuscation, the donation was credited to Prime Trust, which is otherwise spotlighted in internal FTX documents as the home to the bank account Singh would draw upon for gifts to EA folks as well as political donations. (Plenty of Prime Trust money, as Singh testified, came from Alameda Research, which held plenty of FTX customer funds.)

There have been state investigations into the circumstances of this donation—a federally illegal one, having been initially made and registered under a false name—and whether it violated state laws. The Dem PAC surrendered the donation to the U.S. Marshals Service in June, leaving the local party in a financially precarious spot; Matt West told me that many of the state’s elected Dems pitched in their own campaign cash to help carry the PAC above water.* Anyway, this spurred a newfound effort within Oregon for campaign finance reform in the state this year, although that ultimately fell flat. Singh admitted to campaign finance violations as part of his plea deal for the FTX trial.

While many of the figures involved in Flynn’s campaign have continued lying low in the aftermath of the FTX explosion, Balwit has taken on a public communications director role for Anthropic—the heavily capitalized A.I. firm that received tens of millions of dollars in investments from SBF & Co. (Company president Daniela Amodei had also donated to Carrick Flynn’s campaign on Jan. 9, 2022, preceding its FEC registration.) In June of this year, Balwit wrote about A.I. regulation for Asterisk Magazine; her bio mentions her roles at Anthropic and FHI, and that she was selected for a Rhodes scholarship. There’s no mention of Flynn’s campaign. Or FTX.