Sam Bankman-Fried Is Going to Prison. What About Gabe Bankman-Fried?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Slate’s daily coverage of the intricacies and intrigues of the Sam Bankman-Fried trial, from the consequential to the absurd. Sign up for the Slatest to get our latest updates on the trial and the state of the tech industry—and the rest of the day’s top stories—and support our work when you join Slate Plus.

On Thursday, jurors convicted former crypto mogul Sam Bankman-Fried of defrauding his customers out of as much as $10 billion. He will likely spend the rest of his 30s—and possibly his 40s, 50s, and 60s—in prison. The judge is expected to sentence him in March.

As former confidants and close friends testified against him during his monthlong trial, Bankman-Fried’s parents, Joseph and Barbara, showed up day after day to support their son, whose crypto exchange FTX imploded late last year. The Stanford Law professors’ hand gestures and facial expressions played prominently into journalists’ recounts of the proceedings, offering the real-life version of the cutaway shot integral to any courtroom TV show. On Oct. 11, following damning testimony by Bankman-Fried’s former colleague and girlfriend Caroline Ellison, Bloomberg shared that “his mom, Barbara Fried, smiled and waved at him.” On closing-arguments day, the New York Times noted that Bankman-Fried “blinked quickly, glancing back and forth from the lectern to his parents in the gallery.” On Thursday, “after the first ‘guilty’ was read aloud—for wire fraud—his father doubled over. His mother’s hands rose to cover much of her face, either to stifle tears or to hide them,” the Verge reported.

In the cinematic version of this courtroom drama, we’d have gotten a glimpse, here and there, of the fourth member of the Bankman-Fried family: Sam’s younger brother, Gabriel. That never happened, because the Brown computer science grad does not seem to have set foot in the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse.

The professional lives of the siblings, who are three years apart, became profoundly intertwined in 2020, when Gabe founded the nonprofit Guarding Against Pandemics, with help from Sam. Like his older brother, Gabe was an effective altruist, meaning he subscribed to a philosophy focused on a calculated, data-driven approach to figuring out where the smallest amount of money or effort could have the largest positive impact. At first, like his brother, he followed the EA principle of earning to give and worked as a trader at Jane Street Capital. By the time COVID arrived, Gabe had pivoted to politics, working for a data-driven campaigning company and then Sean Casten, a Democratic congressman from Illinois.

Virtually overnight, the creation of Guarding Against Pandemics propelled Gabe from being just another low-level legislative aide to the head of an organization able to deploy tens of millions of dollars to boost legislation, endorse politicians, and support groups that aligned with his cause. As warriors against future pandemics, his team came up with novel ways to fund pandemic research—like taxing Colorado weed sales. (That bill did not pass.) GAP also helped shape the way that major media sites framed Biden’s $30 billion pandemic prevention bill and hosted Republicans and Democratic political operatives in its $3 million Capitol Hill town house/lobbying base.

The fact that most of this funding was coming from Gabe’s brother was never a secret. Sam, at one point, was worth more than $26 billion, and he spent millions with a casualness typically reserved for pennies. But the FTX bankruptcy proceedings and recent SBF trial have raised some complicated questions about that money. At least $10 million of the $17.5 million to $35 million Sam donated to GAP—and maybe much more—came from a mixture of customer and non-customer accounts at his hedge fund, Alameda Research, according to estimates from federal prosecutors and bankruptcy filings. Nishad Singh, the former director of engineering at FTX, made it clear that Gabe participated in a group chat that was used to make political donations under FTX employees’ names. (Gabe Bankman-Fried and Singh are close friends from high school and the reason Singh got involved in Sam’s businesses.) Singh also said that Gabe once flew his assistant to the Bahamas to get Singh to sign a bunch of checks by hand, to make it seem as if the political donations had come from Singh instead of GAP.

And so Gabe’s absence, following years in which he was a bit character in the Sam Bankman-Fried story, piqued my curiosity. Could Gabe be in legal trouble himself? Where did the bulk of Guarding Against Pandemics’ money go? If someone sends stolen funds to his brother’s nonprofit, what happens to that money? And—most fascinatingly of all—had Gabe really planned, as so many have reported, to buy an entire island nation?

Back in February, the New York Times reported that authorities were investigating whether Gabe (and others) had played any role in a suspected scheme to illegally disguise political donations using “straw donors.” Bernie Madoff’s brother was charged with conspiracy to commit fraud about three years after his brother’s sentencing. So, the fact that no charges have come yet for Gabe does not mean they never will. But the latest details don’t provide strong hints about where it’s headed. (In an email last week, a spokesman for the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, which prosecuted Sam, declined to comment, saying that he does not discuss investigations of “uncharged” individuals.)

And Gabe is not going to face charges simply for accepting money that was stolen. “Nonprofits are not legally required to vet the source of their donations,” attorney James J. Hsui explained to me.

That doesn’t mean that Guarding Against Pandemics or the people it donated to get to keep their money. FTX is currently in bankruptcy proceedings. As part of that process, a trustee will likely attempt to claw back all the misappropriated money that Sam Bankman-Fried and his companies spread around. That means, bankruptcy attorney Linda Tirelli predicted to me, that “all hell is going to break loose.” Entities that FTX gave money to—such as GAP and its affiliated PAC—will likely have to give it back to the bankruptcy estate. And PACs and other organizations that these FTX beneficiaries donated money to may have to give it back as well, in a long, messy chain of evaporating funds.

“Guarding Against Pandemics advocates for public investments to prevent the next pandemic,” the group stated in a 2021 tax filing. “Covid-19 has killed over 600,000 Americans and cost this country 16 trillion dollars and experts say that the next pandemic could be right around the corner. GAPS one and only goal is to ensure that never happens again.”

So who were GAP’s beneficiaries? In August 2022, Gabe told Insider that he would dole out money to Republicans and Democrats “who champion pandemic prevention.” Indeed, his Federal Election Commission filings show that his PAC gave small amounts to an array of lawmakers. Richard Hudson, a Republican congressman in North Carolina focused on pandemic preparedness, and Josh Harder, a Democrat in California focused on vaccine access, each received $5,000 in 2022, for example. He also bought an ad praising Sen. Elizabeth Warren and hired a pricey lobbying firm.

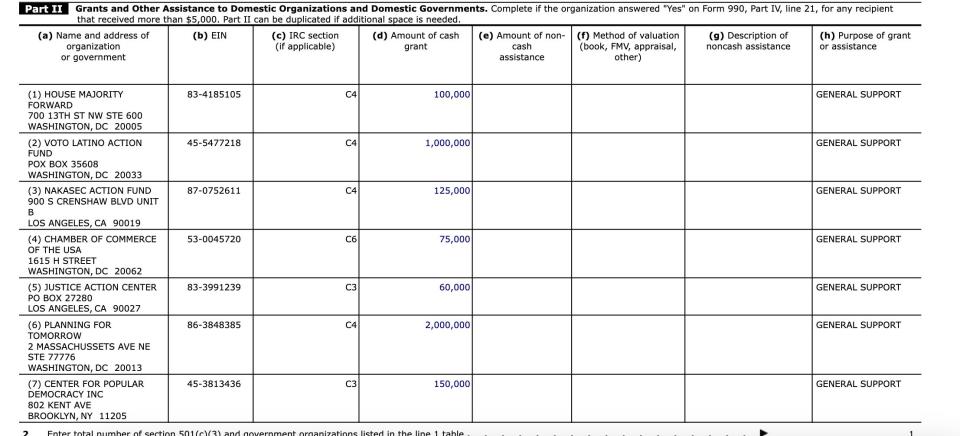

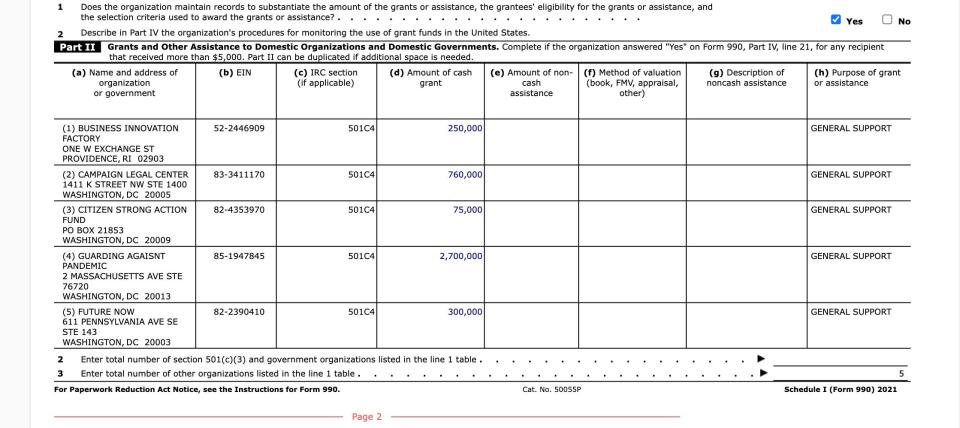

I found myself wondering, though, whether he invested in anything a little less political. Like a public-health tool? After all, when he first launched his nonprofit, he stated on his site that he’d invest in “cutting-edge research” and “technology development.” So I sifted through his 2021 tax filings. (The 2022 filing is not yet available.) And this is where things get odd. GAP gave $2 million, its largest grant in 2021, to Planning for Tomorrow, another organization Gabe also ran. Planning for Tomorrow notes that it is “dedicated to developing young leaders and improving civic engagement.”

And whom did it give money to? Funny you ask. In that group’s tax filing, I found that it gave its biggest grant—$2.7 million—to … Guarding Against Pandemics (misspelled Guarding Agaisnt Pandemic).

In other words, Gabe’s well-known nonprofit, Guarding Against Pandemics, gave its biggest grant to his lesser-known nonprofit, which gave it back to that original bigger nonprofit—all in the same year. Nonprofit experts told me that there are both shady and legit reasons to loop money between two nonprofits you have created. An example of a shady reason: actively trying to obscure where money is coming from and going to—that is, money laundering. An example of a legit reason: giving money to another organization early in the year so it has the funds it needs to do something and, later, when more money comes into that other organization, returning it. Either way, that money was never going anywhere apolitical.

Gabe stepped down from Guarding Against Pandemics last November, about three days after FTX filed for bankruptcy. “I don’t want to be a distraction,” he told his staff at an all-hands meeting reported on by Puck. For a moment, it seemed as if the organization might carry on anyway. In a statement, Keenan Lantz, the new interim executive director, said the work the organization was doing was “vitally important and we hope it will continue.” Lantz was motivated by the organization’s mission, his attorney Andrew D. Herman told me Monday. “Keenan really believed in effective altruism and wanted to make the world better and believed that he was doing this by working with these effective altruists,” he said, adding, after a pause, “And then he finds himself in this situation.”

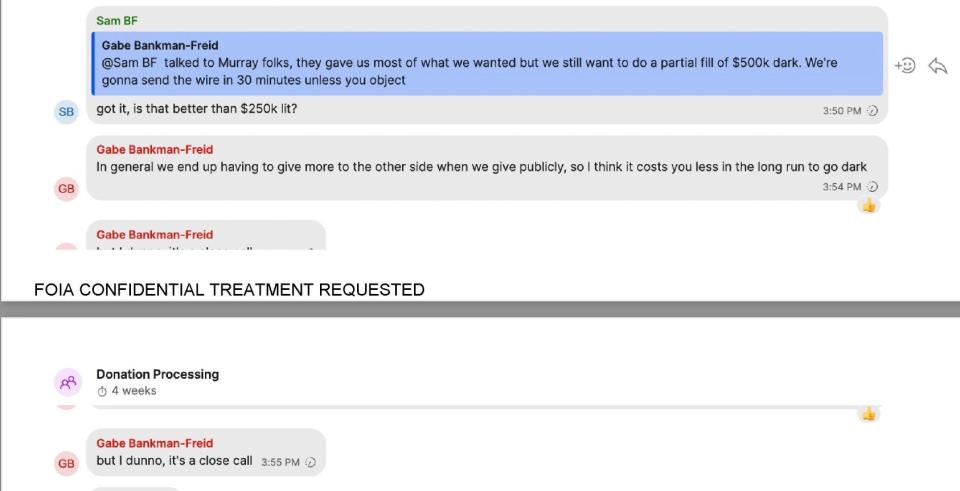

By this situation, Herman may be referring to the fact that rather than halting pandemics, his client had his name end up in one of the biggest fraud trials in decades. During the SBF trial’s proceedings, FTX’s Singh stated that Lantz, in his capacity as the director of operations at GAP, coordinated the sending of money to a Democratic candidate under Singh’s name. This happened in the “donations processing” Signal group chat, of which Gabe was also a member.

We saw a screenshot of that group at the trial. Its existence has turned some formerly supportive effective altruists against the organization. In it, Gabe explained why he liked to “go dark”—as in, make political donations under FTX employees’ names, instead of as Guarding Against Pandemics. No charges have been filed. But Neel U. Sukhatme, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center, told me that if “Gabe Bankman-Fried—either in his individual capacity or as head of his PAC—directed someone at FTX to donate money to a particular candidate or party, that would seem to be a straw donation.” Those are prohibited.

Herman defended his client’s participation in the chat. “Keenan had no involvement in directing anything in surreptitious ways,” he said. Rather, he worked for GAP, and his largely administrative role, as he was assigned it, involved processing donations from FTX employees to PACs. When I noted that this seemed strange, given that he did not work for FTX and that it’s not clear what this money had to do with pandemic prevention, Herman said, “I can’t comment on why that was his job,” noting that Lantz did not play a role in deciding where the money went. Herman also noted that in campaign finance, there isn’t a requirement to justify why you’re making any particular contribution.

“If people don’t like what they see, maybe they mean we should reform our campaign finance systems,” he said.

Regardless, Lantz’s employer will soon be done, according to Stu Loeser, the longtime communications director for New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Sen. Chuck Schumer, who is evidently now involved in protecting the reputation of the nonprofit.

“The organization is winding down,” Loeser told me via email Thursday, after I’d sent a bunch of messages to @againstpandemics.org addresses.

As to what Gabe thinks, we do not know. His lawyer agreed to talk this week—then seemed to change his mind about a phone interview, then declined to answer my emailed questions. Neither his former assistant nor an adviser responded to a request for comment. I reached out to multiple political organizations he gave money to, but once they understood why I was contacting them, they stopped responding. Unlike his brother, who could not stop vomiting out interviews even as lawyers begged him to stop, he was careful with his words.

Though his mother and father spoke extensively to the New Yorker for a piece on the family, Gabe declined. The Twitter profile @bankman-fried shows a single action: In August 2019, he liked a tweet by Casten, that Democrat congressman from Illinois he worked for. (Casten, not so coincidentally, was propelled to office with the help of Gabe’s mother’s data-driven fundraising initiative.) According to Puck, even his responses to friends’ messages regarding the FTX debacle were often limited to a succinct emoji or iPhone reaction: !!

All we really know for sure at this point is that Gabe did not buy the Pacific island nation of Nauru in order to create a human genetic enhancement lab. Believe it or not, there has been a lot of confusion about this. The whole strange subplot goes back to a lawsuit filed by FTX in July against SBF and other former FTX executives. It references a memo outlining a “plan to buy Nauru and build apocalypse bunker” to “create ‘superhumans’ for apocalypse.” Commonly recirculated quotes include using the island in “some event where 50%–99.99% of people die [to] ensure that most EAs [effective altruists] survive” and to develop “sensible regulation around human genetic enhancement, and build a lab there.”

I had to double-check this. As it turns out, the full memo was not included in the lawsuit and the proposal was not written by Gabriel Bankman-Fried—rather, it was “exchanged” between him and an unnamed officer of the FTX Foundation. A few news outlets published a version of this clarification, which never got as much play as the original reports on the Nauru proposal. “Gabriel Bankman-Fried did not create, endorse, contribute to, or draft a plan to acquire the island of Nauru,” his lawyers informed reporters. “In truth, Gabriel received by email a link to the memo, which he did not write or request, and did not forward to anyone else. He did not engage in conversation about the purchase of the island.”

Indeed, simply receiving an email he never read probably does not legally constitute an “exchange,” Tirelli, the bankruptcy lawyer, pointed out to me. We may yet learn more should the full memo emerge. (His lawyer declined to send it to me.) For now, it’s probably safe to say that Gabe Bankman-Fried’s most eyebrow-raising activity was not a plan to buy the island of Nauru.