Samuel Alito Really, Really, Really Wants to Save This Racial Gerrymander in South Carolina

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

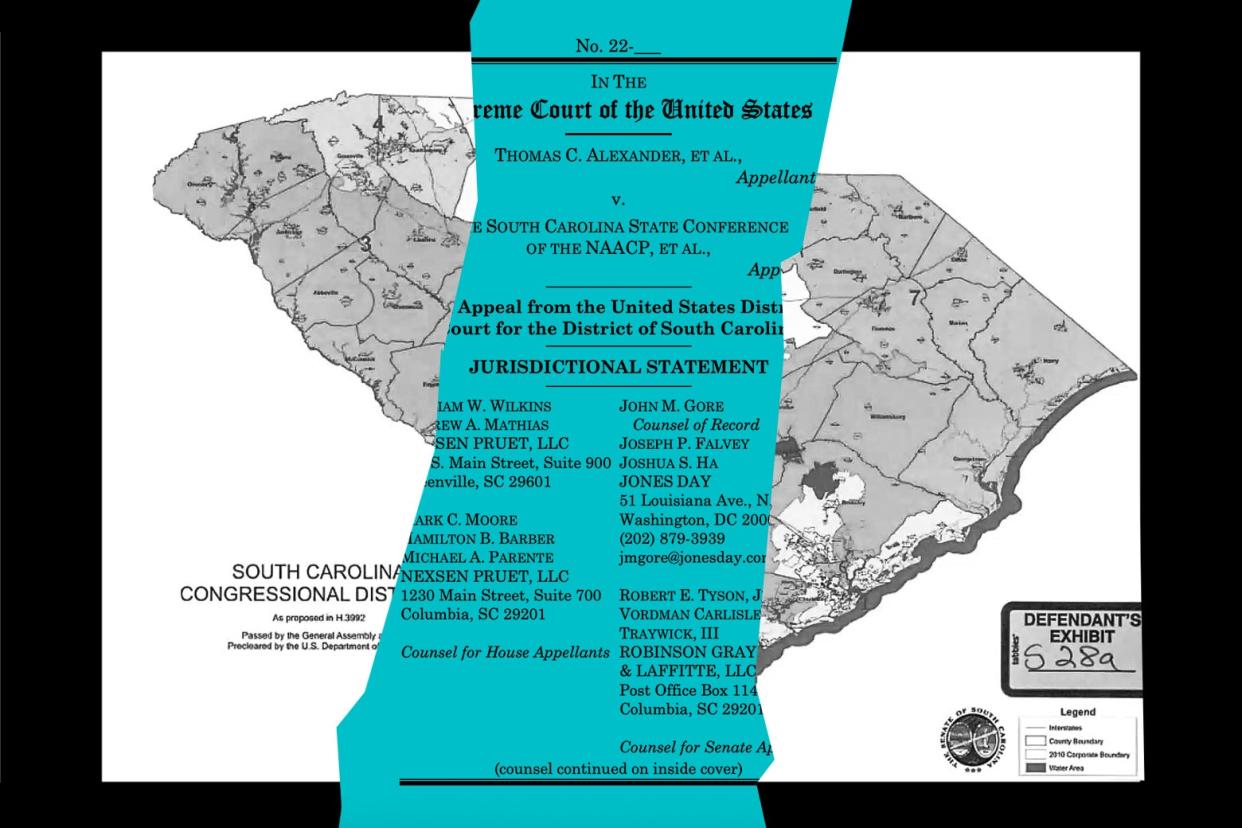

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, a challenge to South Carolina’s congressional map based on the contention that it was an impermissible racial gerrymander. The case should have been easy for the groups that challenged the map, given the applicable law and the arguments advanced by the state’s lawmakers in defense of their map—which was found to be unconstitutional by the lower court.

Unfortunately for the challengers of that map, Justice Samuel Alito had other ideas. After more than two hours of Alito-centered arguments, the question for his other conservative colleagues will be whether they side with him, change the law, and have the Supreme Court serve as a super-trial court in such cases—allowing the high court to reject trial court findings when they come out a way the conservative majority doesn’t like.

This would be a dramatic shift to current precedent, something that Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson kept raising throughout the arguments, with an uncertain degree of success for the purposes of convincing Alito’s fellow conservatives.

A three-judge district court had, after an extensive trial, decided that South Carolina engaged in an impermissible racial gerrymander to one of its congressional districts in violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. When rebalancing congressional districts after the census required moving voters from one district to another, the state didn’t simply move the number of voters required. Instead of moving 90,000 residents out of the overpopulated district and into the underpopulated one, the state swapped more than 50,000 residents into the overpopulated district and moved 140,000 residents out of it. The decisions about who was moved out of the district were done in a way, the district court found, that kept the Black voting-age population in the district at the same level—in part to help ensure that district would remain a Republican district—even as the new demographics of the area suggested the Black voting-age population in the district should increase.

As the lower court concluded:

With the movement of over 30,000 African American residents of Charleston County out of Congressional District No. 1 to meet the African American population target of 17%, Plaintiffs’ right to be free from an unlawful racial gerrymander under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment has been violated.

According to past precedent, overturning the factual findings of that panel—including its weighing of the voluminous evidence and testimony of expert witnesses—would require the Supreme Court to find “clear error” in the district court’s findings. According to that old standard, there is no such clear error in this case, as was clear from Wednesday’s arguments.

It appeared things might be going toward that easy resolution when Justice Clarence Thomas’ first question for John Gore, the South Carolina lawmakers’ lawyer, focused on the “clear error” standard and how the justices would find that in a case like this, where so many fact-bound decisions take place and figured into the lower court’s ruling. Noting that “the district court credited the plaintiffs’ expert and found your experts noncredible,” Thomas asked, “So how does that meet the clear error standard?”

Gore—a Jones Day lawyer who played a key, questionable role in the Trump administration’s failed effort to get a citizenship question on the 2020 census—responded to Thomas by delving into specific arguments about the opinions, data, and conclusions put forward by one of the plaintiffs’ experts at trial.

That, in turn, led Justice Sonia Sotomayor to tell Gore that his argument had “a very poor starting point” if the focus was on the credibility of the expert witnesses—something that ordinarily “must be deferred to” on appeal because that is so central to the district court’s role.

As Jackson explained, under the clear error standard, “A finding [from the district court] that is plausible in light of the full record, even if another is equally or more so, must govern.”

Ultimately, that won’t really matter if Alito has his way. Alito was driven on Wednesday, seeking to undermine—and change—how deferential the “clear error” standard is in gerrymandering cases. Pushing back on the questions that had been posed to Gore by several of his colleagues, especially the three Democratic appointees, Alito stopped to tell everyone that the clear error standard “is not an impossible standard” for South Carolina to meet.

“It doesn’t mean that we simply rubber-stamp findings by a district court, particularly in a case like this, where we are the only court that is going to be reviewing those findings,” he said, a reference to the fact that three-judge district court rulings are heard directly on appeal by the Supreme Court. Further still, Alito argued that it matters here that the decision below “relies very heavily, if not entirely, on expert reports.” From there, Alito segued into a question about a specific issue regarding the analysis of one of the plaintiffs’ experts and a question that South Carolina raised in its final brief at the Supreme Court about “an alleged flaw” in that expert’s analysis.

If Alito was worked up during Gore’s questioning, that was just a warm-up round for the respondents’ argument, when Alito effectively took over for Gore, posing no fewer than 37 questions to the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund’s Leah Aden—including a marathon 19-question session taking up 11 pages of the transcript during his final chance to question her.

He asked Aden about the plaintiffs’ experts, hypothetical redistricting decisions, his “concern” about “what has been said” about the mapmaker whose map was found to be unconstitutional, about a partial plan that had been proposed by Democratic Rep. James Clyburn, and about an ongoing question regarding why the plaintiffs did not propose an alternative map to show that the partisan goals aimed for by the legislature could be met. (To that final point, as Justice Elena Kagan pointed out to Gore earlier in the argument, “The alternative map requirement … doesn’t exist.”)

In comparison to Alito’s 37 questions, the rest of the court—all eight justices combined—asked a total of 28 questions.

If Alito wants to be a district court judge, he’s more than welcome to retire from the Supreme Court and start sitting on district court cases. When it comes to the Supreme Court’s current standard of review, though, the sort of questions Alito was asking are questions that the justices generally aren’t asking—and shouldn’t be asking—in such a case.

As Aden put it at one point, “Are we retrying expert testimony on appeal?”

For Alito and Justice Brett Kavanaugh in particular, it appeared that, for the most part, their answer is yes.

And yet, the outcome of the case isn’t ultimately clear. Justices Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett did ask some questions delving into the nitty-gritty of the district court’s findings, but it wasn’t clear whether those reflected as much antipathy to the clear error standard as Alito expressed Wednesday.

Finally, although Chief Justice John Roberts expressed repeated concern about whether the particulars of this case would be “breaking new ground in our voting rights jurisprudence”—something Aden disputed—Roberts also noted in a question to Gore, speaking about the Supreme Court, “We don’t normally review a record for factual findings.”

As the justices vote on the case and begin to craft the court’s opinion, they will have to decide if that norm is going to be upended in gerrymandering cases—a result that would be another potential barrier to full enforcement of voting rights by the Roberts Court.