San Quentin closure: From The Sacramento Bee archives, Sam Stanton’s award-winning execution story

Bee Staff Writer Sam Stanton won the American Society of Newspaper Editors Distinguished Writing Award for deadline writing in 1992 for his coverage of the execution of Robert Alton Harris at San Quentin State Prison. Stanton witnessed two gas chamber and six lethal injection executions at San Quentin, which California Gavin Newsom has announced will be closing as a prison. The following story is included in “America’s Best Newspaper Writing: A Collection of ASNE Prizewinners.” This Stanton’s story from the April 22, 1992 Sacramento Bee:

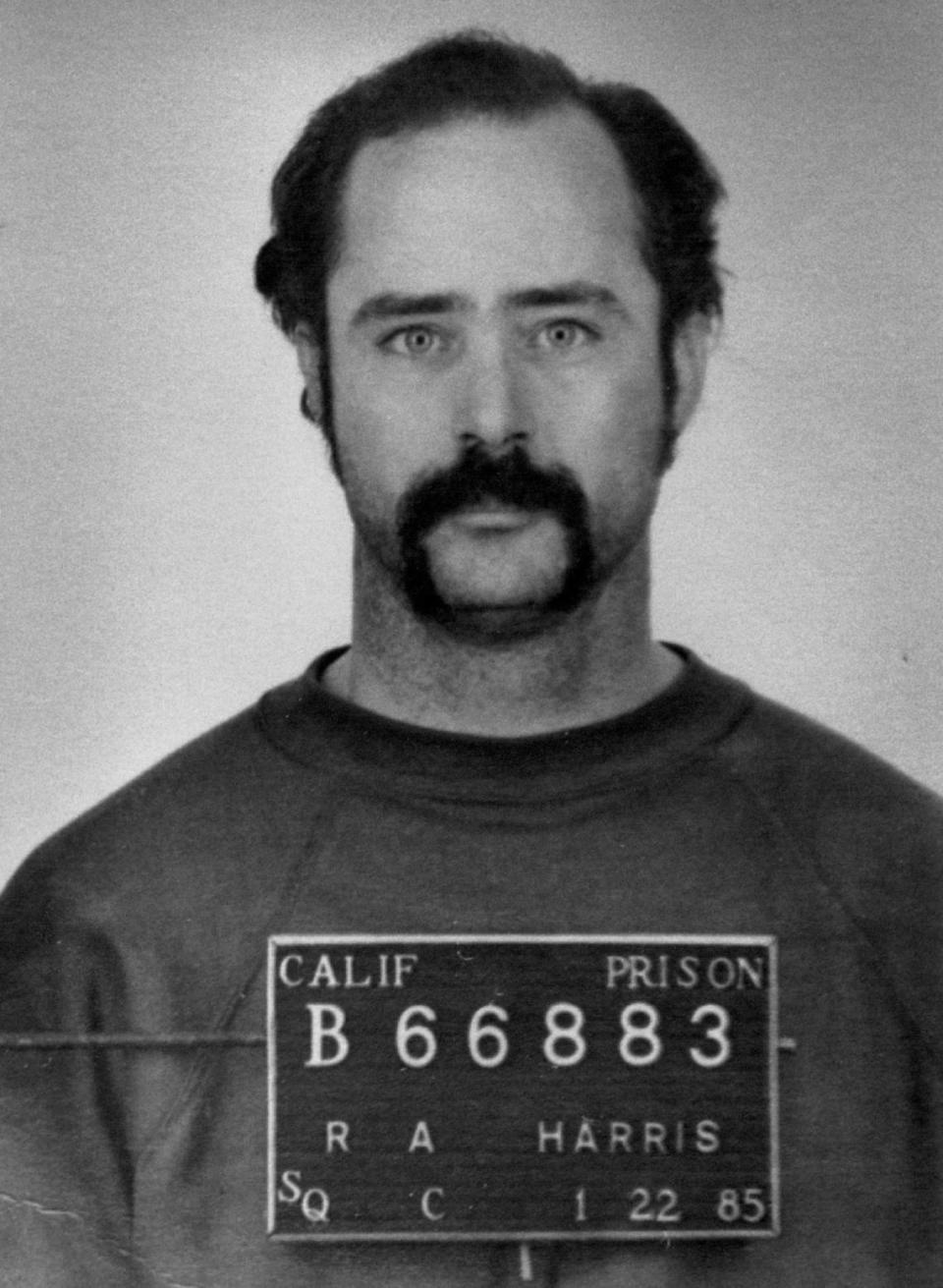

In the end, Robert Alton Harris seemed determined to go peacefully, a trait that had eluded him in the 39 violent and abusive years he spent on Earth.

As the cyanide fumes rose up to his face in the San Quentin gas chamber, he inhaled deeply and stared straight ahead, barely moving until death throes convulsed his body.

His trademark smirk was gone, replaced by a haunting look of sadness spawned by one last hellish night of fighting for his life and two predawn journeys to the gas chamber.

Harris, the murderer of two 16-year-old boys, made his first trip at 3:49 a.m., when he was strapped in a chair for 12 minutes. But with barely a minute to spare before the cyanide pellets were to be dropped, a surprise court order was called in, delaying the execution.

Within two hours he was walked back to the chamber and hurriedly subjected to cyanide gas poisoning that killed him at 6:21 a.m.

His final night was spent in a small metal cell with only a bare mattress, a minister and a constant stream of updates on the legal battles that appeared to have drained him by dawn.

When he entered the chamber for the second and final time at 6:01 a.m., Harris looked meekly at the four dozen witnesses and appeared to accept that after so long, he was going to die for the 1978 murders of Michael Baker and John Mayeski.

He went almost peacefully, mouthing the message to one guard watching, “It’s all right.”

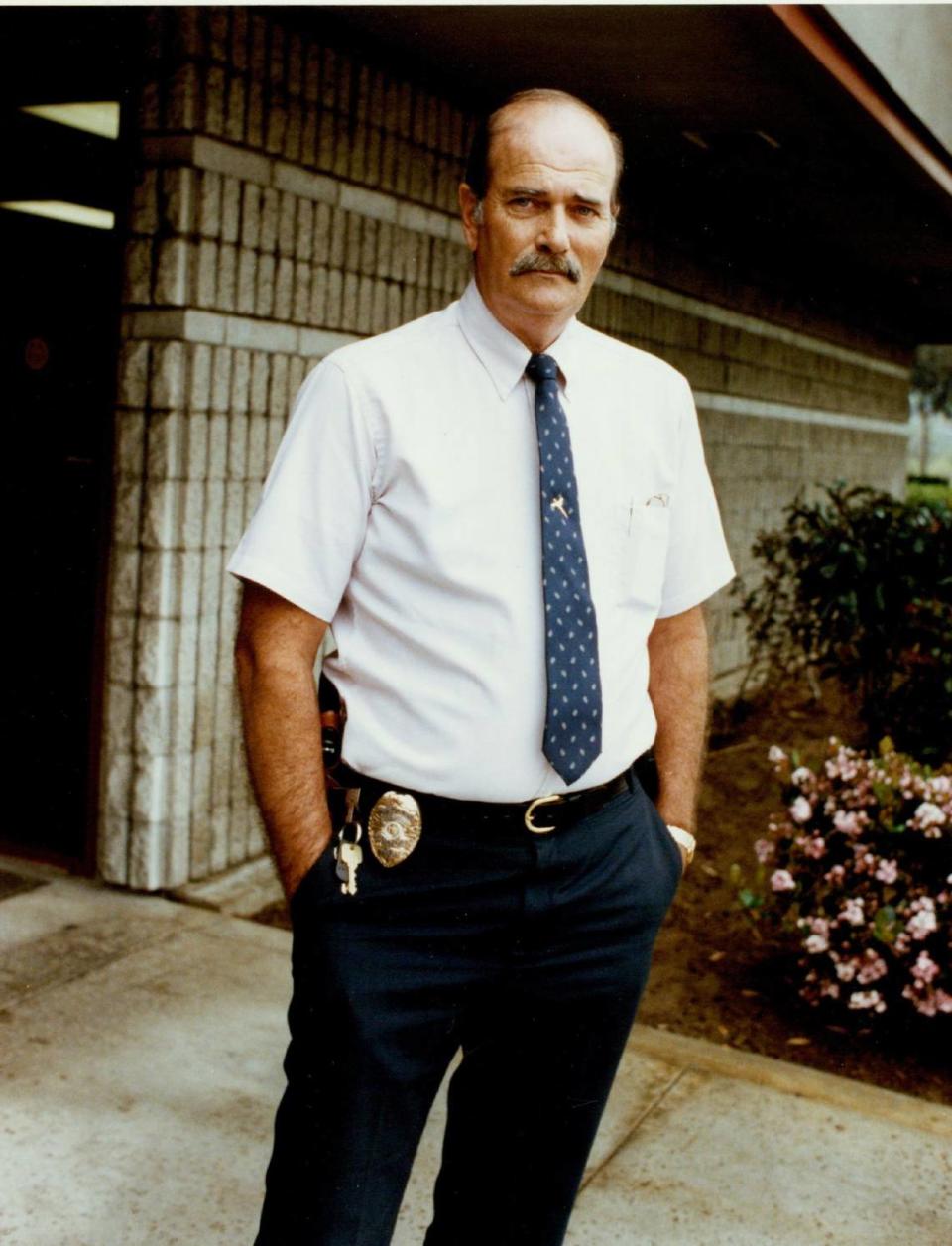

He then craned his neck backward and to the side until he caught the eye of San Diego Police Detective Steve Baker, whose son he had murdered.

“I’m sorry,” Harris mouthed.

Behind the thick windows, Baker nodded back but remained expressionless. The time for remorse had passed, he said.

“When you’re sitting in the gas chamber, saying you’re sorry is a little bit too little and a little bit too late,” he would say later.

Within a minute of Harris’ silent apology, the gas had begun to rise about him, and he sucked it deeply into his lungs.

Within minutes, he gasped, moaned and drooled until his head eased forward into his chest and he died.

Delayed justice and mental torture

Before entering the chamber, Harris borrowed a line from a recent popular movie (“Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey”). “You can be a king or a street sweeper, but everybody dances with the grim reaper,” San Quentin Warden Daniel Vasquez reported him saying.

Yet the bravado appeared to be false.

While other gas chamber victims have thrashed and fought the gas, Harris appeared to give himself up to it.

He never clenched the arms of the chair to which he was strapped, and his muscular body moved in a slow, almost graceful response to the asphyxiation.

He didn’t move after 6:08 a.m. but was not pronounced dead until about 13 minutes later, an event that brought an almost rapture-like smile of joy to the face of Sharron Mankins, Michael Baker’s mother.

Harris’ lawyers had finally failed in their attempts to spare him from the lethal gas on the grounds that it is cruel and unusual punishment.

But the events preceding his death were on a fine line between delayed justice and mental torture.

Scheduled to die at 12:01 a.m. Tuesday, Harris had begun Monday resigned to his fate, officials said.

He bid farewell to some of the guards he had become close to in his 13 years on death row, then moved to a visiting area at 8:30 a.m. to meet with family and friends.

By 6:22 p.m., he had been taken to the condemned prisoner’s cell steps from the chamber, where he was to eat his last meal and spend the last 5-1/2 hours of his life.

Instead, he spent nearly 12 hours there as a federal appeals court in San Francisco and the U.S. Supreme Court fought pitched legal battles over whether he would die.

Stay after stay after stay was handed down by the federal court seeking delays, but attorneys for the state of California pounced on each with appeals that overturned them.

Up until 11 p.m., California Department of Corrections officials were prepared to proceed on schedule with what they call the “execution ritual.”

But the legal battles pushed it back, first past 1 a.m., then 2 a.m., and finally 3.

Outside the prison gates, the anti-death penalty forces had dwindled to a handful, while inside, few noises were heard save the roar of the generators from the television trucks gathered to cover the event.

Stays of execution

But at 3:06 a.m., the word came down swiftly. All 18 media witnesses to the execution were to proceed to two waiting shuttle buses outside. Immediately.

They piled in after emptying their pockets of everything – wallets, pens, pencils, notebooks – except one piece of photo identification.

The shuttles roared off up the hill into the center of the huge prison complex, one racing so quickly toward the death house that its open door slammed into a security gate that was not opened fast enough.

The second followed closely behind, abandoning one witness who was forced to run to the assembly point – a snack bar by the gas chamber building.

“We’re minutes away from execution,” shouted Tipton Kindel, the Corrections Department spokesman.

After searches of all 18, the witnesses were marched out into the moonlit, cloudless night. They moved across a street under the watch of a sharpshooter and several guards, creating ominous echoing bangs as each stepped on a loose manhole cover.

Inside the witness room, friends and relatives of Mayeski and Baker already stood toward the back of the room on two rising platforms. Closer to the death chamber, standing before a railing several feet away from the windows, were more witnesses and relatives.

Away toward a far corner was a cluster of guests Harris had invited, including his older brother, Randall.

At 3:49 a.m., three guards firmly gripping Harris walked him into the chamber and held him while he was strapped into Chair B, one of two inside the apple-green contraption.

He appeared to have tears in his eyes momentarily, but within a minute gave a thumbs-up sign and wink to the onlookers.

He was dressed in a new, short-sleeved work shirt and denim trousers, his brownish yet graying hair pulled back in a slight ponytail.

In the background, a faint ringing could be heard behind the chamber door.

“Oh, God,” gasped one of the women from the Baker and Mayeski contingent.

It sounded momentarily like a telephone ring, and witnesses nervously eyed each other as they considered whether last-minute reprieves came only in movies.

After a minute, the concern appeared groundless. Harris was left in the chamber and the minutes began to tick away as everyone awaited the gas.

At 3:53 a.m. he mouthed to a guard, “I can’t move.”

He looked around. Back to his friends and relatives. Over to four guards standing toward the corner of the witness room. Up at the reporters craning and contorting to see him over the shoulders of those at the railing.

He flexed his hands and shook his head as though agitated, wanting to get it over with. He appeared to shrug toward the reporters.

A few more minutes passed.

Suddenly, a subterranean groaning began to rumble through the room, the sound that might be caused by the release of hydrochloric acid into the holding tank under his seat, with the cyanide packets suspended above.

It was now 3:58 a.m., and even Harris thought it was time. “Let’s pull the lever,” he appeared to say, then laughed.

But another minute passed as he looked about impatiently, and some heard a voice from behind the chamber say, “Turn the water off.”

Still nothing happened, and at 4 a.m. Harris closed his eyes and bowed his head, then looked up again.

Within a minute the chamber door was pulled open suddenly. Burly, purposeful guards expertly unstrapped and hustled him out of the chamber as he looked up in confusion.

“Ladies and gentleman,” prison spokesman Vernell Crittendon began to say.

But it was obvious. There was another stay of execution.

The witnesses were escorted out, and they learned that Harris had been within minutes of death when a judge telephoned the prison to delay the execution. The groaning sound they heard was the acid being withdrawn from the reservoir as officials rushed to put the brakes on the ritual.

Outside, officers escorting the media witnesses assumed wrongly that the execution had been carried out.

“Devastating, huh?” one said after seeing the shocked looks on the faces of those emerging.

It was – but to the Baker and Mayeski relatives, not to the Harris guests.

Marilyn Clark, a sister of Mayeski who had tears in her eyes through much of the ordeal, looked stunned.

Linda Herring, Michael Baker’s sister, grabbed her head in disbelief. California Attorney General Dan Lungren’s face fell with disappointment.

Across the room, Harris’ friends and relatives stood in shocked silence, holding their hands and their breath at the thought that he might be saved once again.

Final legal fight

All the witnesses were returned to their waiting areas away from reporters while prison officials announced the state’s intent to overturn the stay.

By 5:45 a.m., Harris had lost his final legal fight. Once again, the reporters were rushed onto the buses. They roared off again, this time stranding two witnesses who had to hitch a ride in a car.

The searches this time were quick, and the officers hurried the witnesses into the chamber.

The other witnesses already were present, and at 6:01 a.m. a pumping sound could be heard. This time, it was clear the acid was flowing inward to the tank under the chair.

In the same minute, Harris was brought in once again, and three guards strapped him in.

This time, there was a noticeable difference. He appeared almost as lifeless as he would be in a matter of minutes.

His face was etched with lines, and his eyes were large and sad looking. He barely appeared to move on his own, apparently drained by the sleepless night and the emotional toll of the event two hours before.

He shut his eyes, then opened them and mouthed “It’s all right” to a guard and “I’m sorry” to Baker.

By 6:05 a.m. it became clear that Harris would die. No one heard the pellets plunk into the holding tanks of acid, nor saw the gas rise up.

But he suddenly began breathing in and out very forcefully. His eyes rolled into the back of his head, which leaned slowly forward and then all the way back.

A few minutes later it moved forward again. At times, his mouth was half-open. At others, his eyes were slits.

He convulsed involuntarily, and moaned, then gasped and convulsed again. He took deep breaths of the poison air as his head moved slowly forward again, then shook with yet another convulsion.

At 6:07 a.m., Harris appeared to finally be at rest. His head was bowed forward on his chest, and his eyes were closed.

But a minute later his body struggled for survival as his head moved upward with a gasp, then down with another.

He began to drool, and his body once again was wracked with convulsions.

By 6:12 a.m., his body gave up the fight and Harris slowly died.

“The boy’s dead,” whispered one witness from near the Mayeski and Baker relatives.

Sharron Mankins grinned. She had carried the pain for so long of the description of the boys’ deaths.

She knew the story well: how Harris riddled the boys’ bodies with bullets after stealing their car for a bank robbery; how he had chased one down and told him before he killed him, “God can’t help you now, boy. You’re going to die.”

She had heard the claims that Harris was not responsible, that he had been abused from before premature birth when his father kicked his mother in the womb, that he had been subjected to fetal alcohol poisoning, that he had been repeatedly abused as a child.

But she and the others had maintained that their pain could be eased only by the finality his death would bring.

Marilyn Clark looked upward.

Linda Herring stood pensively, her arms folded across her chest.

But the minutes dragged on.

By 6:16 a.m., Crittendon glanced nervously at his watch.

In the next minute, relatives of Harris’ victims began to whisper among themselves.

Before that, most in the chamber had been silent, except for the reporters who whispered descriptions and times to each other.

At 6:20 a.m., clanking sounds could be heard faintly in the rooms behind the chamber, and two minutes later there was a knock on the steel-riveted door that led from it to the witness room. It opened slightly, and a piece of paper was thrust out.

A guard read the wordy announcement that contained a simple message:

Robert Alton Harris had been declared legally dead at 6:21 a.m.

The witnesses filed outside, into the bright sunlight.

After 25 years and nine days, California’s gas chamber was back in operation.

Robert Alton Harris’ last 12 hours

April 20, 1992, 6:22 p.m.: Harris taken to a deathwatch cell near the gas chamber. Spiritual adviser talks with him from adjacent cell.

6:30 p.m.: Temporary stay of execution by 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Appellate judges will be polled.

8:15 p.m.: Harris is served his last meal.

10:30 p.m.: Second stay. Full court to decide whether to refer gas chamber suit to 11-judge panel. State asks U.S. Supreme court to lift both stays.

11:20 p.m.: U.S. Supreme Court vacates the stays of execution.

11:30 p.m.: 9th Circuit judge imposes third stay.

11:45 p.m.: Harris is issued new set of clothing.

April 21, 1992, 12:30 a.m.: U.S. Supreme Court receives appeal. Execution pushed back past 1 a.m., then 2 a.m., and finally 3 a.m.

3:00 a.m.: Supreme Court throws out both stays.

3:49 a.m.: Harris is strapped into chair in gas chamber.

4:01 a.m.: Fourth stay is issued. Harris leaves chamber.

4:15 a.m.: Supreme Court receives the last appeal.

5:45 a.m.: Court overturns appeal and issues order barring all federal courts from granting any more postponements.

6:01 a.m.: Harris returns to the gas chamber.

6:05 a.m.: Pellets drop into holding tanks of acid.

6:12 a.m.: Harris stops all movement and appears to die.

6:21 p.m.: Robert Alton Harris is pronounced dead.