Sanders has a convenient change of heart on delegate rules. Will Democrats buy it?

One of the qualities that fans of Democratic front-runner Bernie Sanders like most about him is that he’s been saying the same things for decades: on universal health care, on income inequality, on “political revolution” and so on.

But there’s one big issue that Sanders has reversed himself on — and it could complicate his path to the nomination.

The issue is the role of so-called superdelegates at the Democratic convention. These are the elected officials and party leaders who are automatically seated but whose votes only come into play after the first ballot.

At last week’s debate in Las Vegas, moderator Chuck Todd asked each candidate whether “the person with the most delegates at the end of this primary season [should] be the nominee, even if they are short of a majority.”

Sanders currently leads the party’s delegate count. The latest polls suggest that he will widen his lead next week, when 16 states and territories — including the big prizes of California and Texas — vote on Super Tuesday. But as Todd pointed out, the same polls also suggest that, because of this year’s fragmented field and the way delegates are apportioned, there’s “a very good chance none of you are going to have enough delegates to the Democratic National Convention to clinch this nomination.”

To get nominated on the first ballot in Milwaukee this July, a candidate needs a majority of pledged delegates — the ones who are selected by voters in the primaries and caucuses. If no one prevails in the first round, the convention proceeds to a second ballot, on which the 3,979 pledged delegates are free to back whichever candidate they choose, and the 771 superdelegates also get to cast a vote.

The question Todd posed was whether the candidates would agree in advance that the party should nominate whichever candidate comes into the convention with the most delegates.

“If that happens, I want all of your opinions on this,” Todd said. “Yes or no, leading person with the delegates, should they be the nominee or not?”

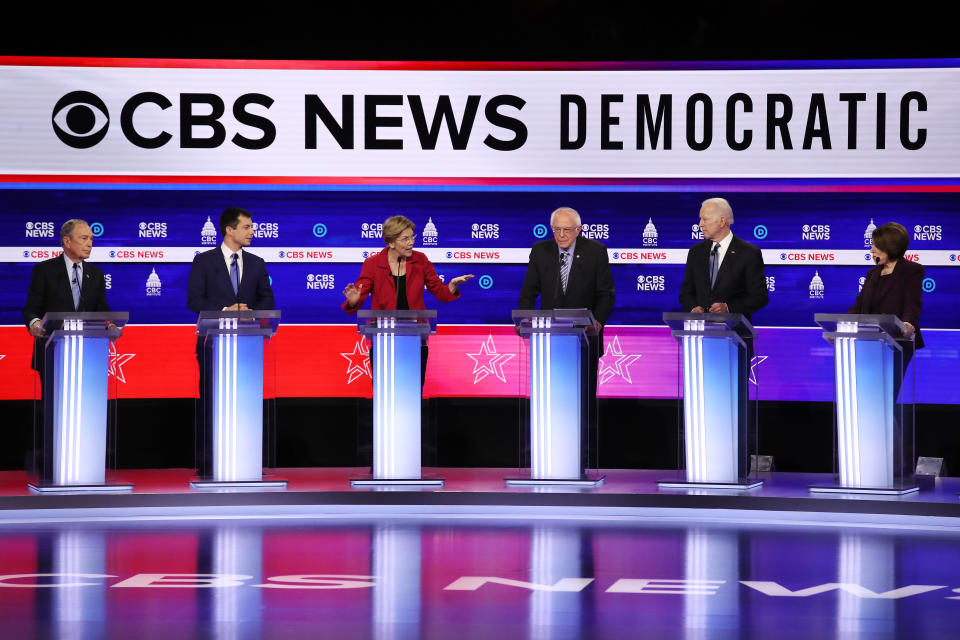

One by one, every candidate on stage — Mike Bloomberg, Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar — offered up the same answer.

“No,” Biden said. “Let the process work its way out.”

“Not necessarily,” Buttigieg agreed. “Not until there’s a majority.”

Finally, Todd came to Sanders. He was the only candidate who answered yes.

“The will of the people should prevail,” Sanders said. “The person who has the most votes should become the nominee.”

Sanders’s position makes perfect populist sense — especially for a candidate who won the most votes in the first three nominating contests and is leading in the national polls.

The problem is that Sanders spent much of 2016 arguing that the person who had the most votes that year — his rival Hillary Clinton — shouldn’t become the nominee, and that superdelegates, defying the “will of the people,” should choose him instead.

At a CNN town hall Wednesday in Charleston, S.C., Warren pointed out that this was, in fact, “Bernie’s position in 2016, that it should not go to the person who had a plurality.”

“And remember, his last play was to superdelegates,” she added.

Warren is correct on all counts.

It’s tough to untangle Sanders’s 2016 stance on superdelegates, if only because it kept shifting. In February of that year — after Sanders shocked the Democratic establishment by effectively tying Clinton in Iowa and trouncing her in New Hampshire — his campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, said on MSNBC that “if the people in the states choose Bernie Sanders over Hillary Clinton, I cannot imagine that the superdelegates would overturn the will of the people.” In 2016, the rules were different than they are now: Superdelegates could vote on the first ballot, boosting their chosen candidate to a majority, and they could make their preferences known long before the convention. Clinton, the Democratic insider, had already amassed a huge superdelegate lead by that time. The Sanders campaign’s argument was the same as the one he’s making today: Support the candidate “who has the most votes.”

Then ... something changed. After a 48-point loss in South Carolina, Sanders fell behind Clinton in the pledged delegate count. He never caught up. As a result, his arguments about superdelegates grew increasingly baroque. The turning point came in late March. Fresh off resounding wins in Alaska, Hawaii and Washington state, Sanders debuted two new talking points.

The first was that superdelegates should “rethink their position with Hillary Clinton” because some polls showed Sanders doing better in a hypothetical matchup against Donald Trump. (At that point, Clinton was ahead by roughly 675 delegates.)

“The responsibility that superdelegates have is to decide what is best for this country and what is best for the Democratic Party,” Sanders elaborated a few weeks later, on May 1. “And if those superdelegates conclude that Bernie Sanders is the best candidate, the strongest candidate to defeat Trump and anybody else, yes, I would very much welcome their support.”

Sanders’s second talking point almost directly contradicted the first. The will of the people was no longer paramount, Sanders seemed to argue in the same late March interview, except “in states where we win by 40 or 50 points.” In that case, the senator continued, “I think [the superdelegates’] own constituents are going to say to them, ‘Hey, why don’t you support the people of our state, vote for Sanders?’”

“If I win a state with 70 percent of the votes, you know what? I think I'm entitled to those superdelegates,” Sanders added in May. “I think the superdelegates should reflect what the people in the state want.”

Either way, Sanders said, “it is virtually impossible for Secretary Clinton to reach the majority of convention delegates by June 14 — that is the last day that a primary will be held — with pledged delegates alone. ... She will need superdelegates to take her over the top at the convention in Philadelphia.”

“In other words,” he concluded, “the convention will be a contested contest.”

As analysts noted back then, Sanders wouldn’t have caught up to Clinton even if all the superdelegates from states he won in a landslide suddenly came to his rescue. And so his team kept arguing that even superdelegates from Clinton states should jump ship, either because he was more “electable” (when surveys showed him beating Trump”) or because he had more “momentum” (when he hit a favorable part of the calendar). In fact, they continued to make this self-serving argument through the last big primary in California on June 7 — even as Clinton was poised to win a majority of pledged delegates that day.

“Superdelegates are different than pledged delegates,” Sanders told NBC’s Lester Holt. “Superdelegates have a very important decision to make.”

“Are you going to try to turn them?” Holt asked.

“Yeah, we are,” Sanders said. “We’re on the phone right now.”

“You’d be defying history,” Holt interjected. “You’d be defying the will of the voters.”

“Well, defying history is what this campaign has been about,” Sanders replied.

Sanders didn’t officially endorse Clinton until more than a month later — in part because he was trying to leverage his support in exchange for the power to rewrite the rules for 2020 at that summer’s convention in Philadelphia.

Ultimately, Sanders got his wish, and his team was largely responsible for the rule change that relegated superdelegates to the second ballot this time around.

That means that Sanders 2020 isn’t just flip-flopping from 2016. By insisting that his rivals should simply step aside if arrives in Milwaukee with a plurality of pledged delegates, but short of a majority, he’s effectively trying to get around the very rules he put in place.

“Those are the rules [Bernie] wanted to write,” Warren said during her CNN town hall Wednesday. “Everybody got into the race thinking that was the set of rules. I don't see how come you get to change it just because he now thinks there's an advantage to him to doing it.”

Sanders is right to worry about what might happen at a contested convention. As the New York Times reported Thursday, “dozens of interviews with Democratic establishment leaders this week show that they are not just worried about Mr. Sanders’s candidacy, but are also willing to risk intraparty damage to stop his nomination at the national convention in July if they get the chance.” In fact, after Sanders won the Nevada caucuses, the Times interviewed 93 party officials, all of them superdelegates, and “found overwhelming opposition to handing the Vermont senator the nomination if he arrived with the most delegates but fell short of a majority.”

Meanwhile, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi brushed off a question Thursday about whether Democrats would support a plurality candidate at the convention this summer.

“The person who we nominate will be the person who has a majority plus one,” Pelosi told reporters at her weekly news conference. “That may happen before they ever get to the convention, but we’ll see.”

This is why Warren, for instance, said yes on Wednesday when CNN asked whether she would continue campaigning through the convention “even if another candidate arrived ahead of you” in the delegate count.

“As long as they want me to stay in this race,” she said of her supporters and small-dollar donors, “I’m staying in this race.”

There’s five months to go until Milwaukee. Sanders’s rivals could falter and fade; he still has a better chance to secure a pledged-delegate majority than anybody else. But if he doesn’t, another candidate might start to look more “electable.” Someone else might start to gain “momentum.”

Sure, Sanders and his supporters will cry foul and shout about “will of the people.” But don’t expect the superdelegates to be swayed. After all, he said the opposite four years ago, when saying the opposite suited him. His opponents this time are signaling that they will hold him to his position.

Read more from Yahoo News: