Former Sandista leader's political novel is banned by the government he helped forge

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sergio Ramírez's most recent novel has become a prohibited book in his native country of Nicaragua. Its copies remain, held without any justification, in some dark corner of a customs office of President Daniel Ortega's government.

Thus, along with "Ulysses," "1984," "Lady Chatterley’s Lover," "The Satanic Verses" and other literary works that have been banned, Ramírez's latest work, "Tongolele no sabía bailar" ("Tongolele didn't know how to dance") is read clandestinely yet massively throughout Nicaragua.

“We pass it on WhatsApp. There are private reading groups in the universities. The boys from the schools show it to their parents. Closed forums were created on Facebook. What is happening with that novel is crazy," said Juan Pablo, an anthropology student at Nicaragua's National Autonomous University of Nicaragua. He is not being identified by his full name because, like many people in the country, he fears the government's repression.

But in a world dominated by the internet, stopping the distribution of a novel in its physical format only encourages online reading and increased interest in all of an author’s body of work — nothing better for a book.

“All forbidden books have appeal. I believe that to induce a young person or a child to read, the best way is to lock up some books with a label that says ‘forbidden.’ That child will find a picklock to read it," Ramírez said with a smile on a video chat with Noticias Telemundo, speaking from Madrid, where he lives.

Government prosecutors accused Ramírez last month of “laundering money, property and assets; undermining national integrity, and provocation, proposition and conspiracy” and ordered the search of his home.

It was then that Ramírez, who has won some of the most prestigious Spanish-language awards, including the José Donoso Ibero-American Literature Prize (2011) and the Cervantes Prize (2017), began to see his stay in Europe, for health reasons, as an imposed exile.

It's also like experiencing the same injustice twice.

“In these things, what I call the philosophy of aging helps, seeing things through another lens. When Somoza accused me of the same crimes in 1977, I saw the world differently," he said, referring to charges brought by the dictatorship of the late Anastasio Somoza.

"I said, ‘Well, this is an incentive for me to continue fighting,’ and I returned to Nicaragua, challenging Somoza," Ramírez said wearily.

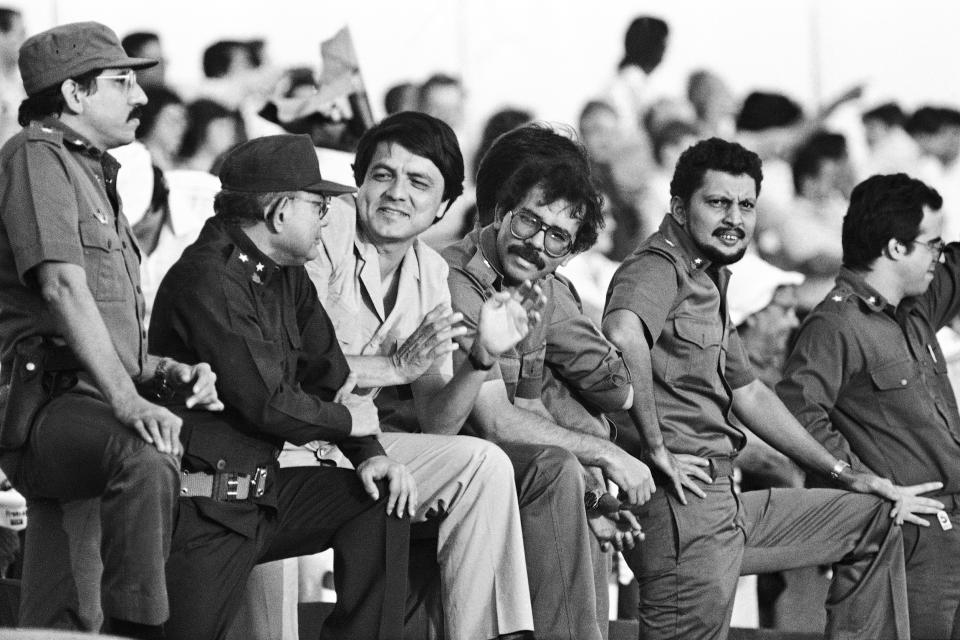

Apart from his acclaimed literary career, Ramírez is one of the founding leaders of the Sandinista Revolution, which toppled the right-wing government and ushered in a socialist revolution. He became the country's vice president until he broke from politics and, above all, from Ortega's Sandinista leadership in 1990.

More than four decades after the victory of Sandinismo, he is once again persecuted by a repressive regime, but this time under Ortega, whose dictatorial government is a vengeful specter of all the dreams of Ramírez’s generation.

“Exile, at whatever age they impose it on you, is a disgrace," Ramírez said. "But I think the worst thing that can happen to a writer is to be exiled from their [native] language. This is what happened to Milan Kundera or Sándor Márai, because the Hungarian language and the Czech language are insular. In that case, if they ban you within your country, you remain speechless, they cut out your tongue, whereas banning me in Nicaragua —there's digital media and, secondly, I have a vast language, a language that has no internal borders," he said.

The ghost of Sandinismo

Ramírez is the most recent target of the repressive and totalitarian machine imposing itself in Nicaragua. As the next presidential elections approach in November, more than 130 political prisoners are being held to silence dissidents and dismantle opposition movements and institutions.

However, Ramírez always goes back to literature.

Why a government that controls the country's armed forces and security apparatus is afraid of a novel, preventing its arrival in bookstores, has to do with Ramírez's role: Since 2018, he has been a fundamental voice in denouncing the government's strategy of repression. In 2018, Ortega's government clamped down on protesters, leading to the deaths of hundreds of people and the exiles of 100,000 Nicaraguans.

In "Tongolele," Ramírez captures the atmosphere of the months of attacks and persecutions in 2018. The book is the final volume of a detective trilogy starring Inspector Dolores Morales, a disenchanted ex-guerrilla who lost his leg in the battles against the Somoza dictatorship.

In another reality, Morales would have been a hero for the rest of his days, but in Ortega’s Nicaragua, he was forced to resign from his police job because of his stubborn denunciations of prevailing corruption.

In the book, his great nemesis emerges: Anastasio Prado, head of the dictatorial secret services, who is called Tongolele because of his white lock of hair, reminiscent of the legendary actor Yolanda Montes, whose streak of white in her dark mane was known throughout Latin America.

Ramírez said Morales, the main character, "is a cynic, but he blindly believes that he is helping to preserve a regime that represents a revolution that no longer exists."

"He believes that all this contributes to the consolidation of that power, that anything goes, that the rest is bourgeois ethics, because proletarian ethics is something else," Ramírez said. "This is very marked in a sector of the traditional left in Latin America that defends these old projects, already out of date, as if they still had a future, as if they had something to offer."

Against the backdrop of social misery and the decline of political leaders who are increasingly old and corrupt, Ramírez sketches a sharply current novel that portrays with acid wit the end of the revolution that he himself helped to forge.

“Bans always arouse curiosity, especially political bans. So my aspiration at the moment is obviously to have a lot of readers," Ramírez said with a laugh.

“I'm not interested in it being a passing book on current Nicaraguan issues or because it's been banned, but rather that it's seen for what it is: a political novel, because it touches on realistic current issues, but also magical, because it touches on that magical regime, based on esoteric values, that we have in Nicaragua."

Noticias Telemundo asked Ramírez several questions about the book.

NT: Anastasio Prado serves as a reflection of mediocre officials who perpetuate social control in totalitarian systems. Have you met many such bureaucrats in Nicaragua?

SR: I have always been interested in novels with a political theme. Not the figure of dictators as such, because dictators become marginal figures, but how they come to modify the lives of those below, those who belong to the repressive apparatus.

After all, Tongolele becomes a tragic character because he ends up being the victim of the same repressive machinery that he helps move. It is a world full of betrayals, duplicities, falsehoods, and that is what I was interested in highlighting. Highlight the characters of the secondary framework, who are the ones who, after all, make up the story, the ones who make the story.

NT: There is great use of dialogue and historical references in your works. Is this aesthetic commitment deliberate?

SR: Yes. I believe that the novels should serve as living histories of the countries. Fiction has that pedagogical value that perhaps it does not intend, but it teaches better than a history book full of statistics and dates would teach. We learned our country’s history by repeating the dates and places of battles, but we did not get to know the soldiers who were behind it, those soldiers with [Simón] Bolívar who crossed the Andes barefoot, sick. That to me is the story, the feat.

NT: What differences do you perceive in the noir crime genre cultivated in Latin America and the classic detective stories?

SR: In the classic novel — the most popular is that of Agatha Christie — the police inspector begins to tie all the strings and at the end he has the luxury of sitting the suspects in a room and explaining to them who the culprit is. That has impeccable and relentless logic. In Latin America, there is no logic. Because power has no logic and power controls everything.

In other words, Inspector Maigret [the lead character of Georges Simenon's crime novels] knows that he is afraid of the judge and the prosecutor, but that is within the order established by law. But it is different in a corrupt judicial system, where the police and the prosecution are all arms of the same power.

NT: That is an aspect that you have deeply explored in your most recent novels.

SR: It is not possible to understand that logic from the perspective of the Cartesian detective novel, where everything is fulfilled according to a pre-established scheme. That is why it seems to me that there is an important modification in what the Latin American crime novel is, because it is penetrated by crime.

The police are accomplices or flirt with drug trafficking. They don’t mind locking up a prisoner and beating him up in an interrogation room. That would be a sin in a British crime novel.

NT: There is a lot of chance in Inspector Morales’ trilogy. Did you want to show how the search for justice is a titanic task for many people in the region?

SR: Well, unfortunately, in Latin America the bad guys get away with it. Many evil ones die in their bed, quietly, or surrounded by millions. Someone who embezzled PDVSA [the state oil company] in Venezuela has a life in Italy or France, and nothing happens to him.

NT: In many of your works there's a narrative of disenchantment; Morales emerges as a witness to the shipwreck of his ideas. Why choose an old guerrilla to tell the end of the Sandinista revolution?

SR: Inspector Morales is an old guerrilla who grows old as the revolution ages. The revolution becomes a ghost. And he is seeing that with a critical eye. ... What was the use of losing a leg fighting against a regime if now this other regime looks so much like that one?

That, in a person’s life, is a drama. And I believe that in Nicaragua, there are many like Morales who make this reflection and ask: Why? For that? It’s a very screwed-up, very dramatic question.

NT: You are part of that group of Latin American leaders who bet on revolutions to change their countries. Do you think there is a future for leftist governments in Latin America after all the corruption and repressive scandals?

SR: It seems to me that there is an error when viewing the left as a homogeneous whole. I believe that if a ghost haunted Latin America in times of armed revolutions, it was social democracy. Social democracy was the great enemy of revolutions, more than the right, because it was a deceptive disguise for capitalism, and therefore social democratic regimes were despicable.

Today the modern left in Latin America is willing to respect electoral results. It is very different from the authoritarian left that only sees elections as a means to seize power and stay there. That left that by blindly defending power ends up ruining countries, isolating and sinking them, what is its reason for existing?

But the left that contributes to the modernization of democratic systems, of electoral systems, seems to me to be worthwhile, and I am referring to the Broad Front in Uruguay, the Socialist Party in Chile or the Brazilian Socialist Party.

NT: Do you still consider yourself a man of the left?

SR: In that sense, yes, because I keep my ideals about change. I believe that Latin America is the most unequal continent in the world, and that needs corrections. It's not about a market economy but about compassionate and humanitarian rules, which is what I think the democratic left represents.

NT: Why do you think the Ortega regime felt threatened by "Tongolele"?

SR: I believe that authoritarianism or dictatorships of the left or right are enemies of the written word. And one has to clear not only [enemies] of words that inform — they attack the media and shut them down —but also of the creative word, that is to say, that a regime believes that it is threatened by a novel and orders its ban seems to me a very weak system.

NT: Did you ever think that this novel would have such an international impact?

SR: I think my case has served as a trigger to make the situation in Nicaragua known through the ban, persecution and criminalization of an author. And, through that window, people have been able to look at what they don't know or have forgotten: that the presidential candidates are all imprisoned, the political leaders, peasants and youth, as well.

There's persecution and thousands of exiles. That is what is behind the novel. I have had the privilege of opening that window and allowing people to take a look at what is happening in Nicaragua.

NT: How do you think history will judge the legacy of leaders like Fidel Castro and Daniel Ortega?

SR: I think there was a heroic time of the revolutions in which Fidel Castro embodied the rebellion of Latin America, the resistance against imperialism, but it seems to me that this reading of history has changed a lot. In 20 or 30 years, Castro is going to be seen as a tyrant rather than a liberator. He is a person who ruled a country for 60 years. That’s the most remarkable thing, isn’t it?

In Ortega’s case, he was a dark figure since the revolution. He wasn’t Castro, who captivated with his snake-charmer glow. Ortega was never that, but rather a dull and shy man. Ortega’s fame is going to be what he earned in 2018 with the murder of about 500 young people on the street. Nobody can erase that.

Furthermore, among the young people of Nicaragua, the Sandinista revolution has fallen into the most complete discredit, if not forgotten. Nobody wants to know about armed struggle. Nobody wants to know about confrontations. That is why the 2018 insurrection was peaceful. They were unarmed boys wanting change but are not willing to take up arms.

NT: Would you like to be remembered for your literary work or for your political legacy?

SR: I think that a writer survives in his books and that there are some books that people prefer more than others. A French friend told me that when a writer disappears, he goes to purgatory. And from purgatory he can go to the hell of oblivion or the heaven of survival.

There are writers who when they disappear they stop being read. It is like a law of life. And years later they are recovered again. It is a great unknown, but obviously I would like to be remembered for my books, not for my political life, which is an asterisk. What I’ve wanted all my life is to be a writer.

An earlier version of this story was originally published in Noticias Telemundo.

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.