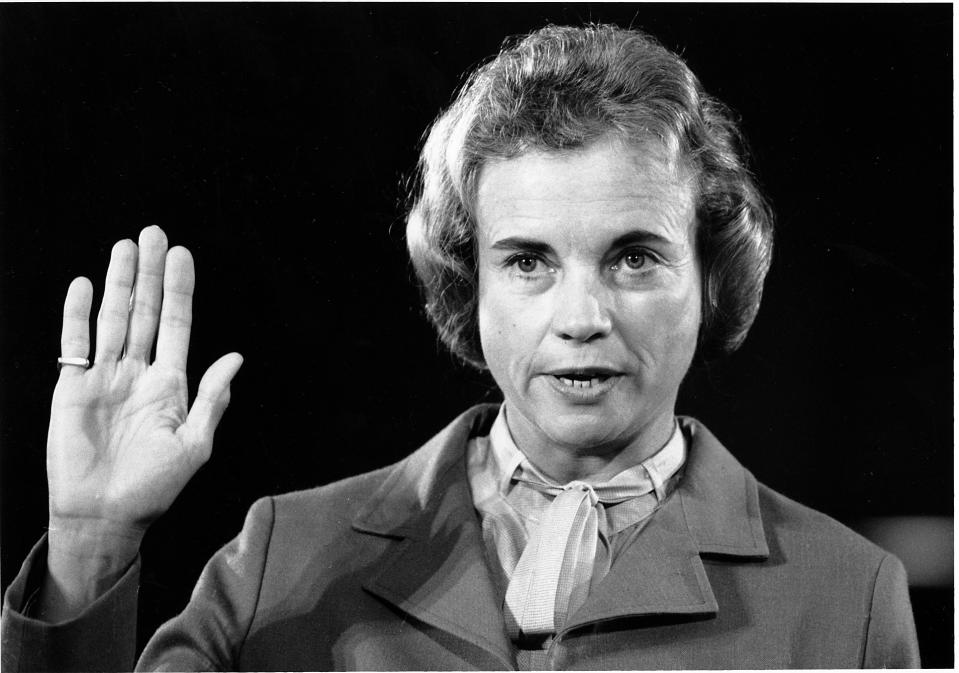

Sandra Day O'Connor reached for a middle ground. Would she fit in at the Supreme Court now?

WASHINGTON − Sandra Day O'Connor, the trailblazing Supreme Court justice who died Friday, built a reputation over nearly a quarter century of finding compromise in some of the nation's most intractable controversies.

For critics of today's Supreme Court, her death underscored just how much times have changed.

Two of her best-known opinions − a landmark case that for three decades established the nationwide standard for abortion access and another upholding the limited use of affirmative action in admissions − have been abandoned in recent years by the current court's conservative majority. O'Connor was also an architect of a campaign finance decision in 2003 that was significantly undermined by the Citizens United decision years later.

Opinions: 'Audience of one.' A look at some of Sandra Day O'Connor's biggest Supreme Court decisions

The departure from O'Connor's approach in those cases underscore a shifting landscape not only on the nation's highest court but also in American politics broadly as compromise has become harder to find. As the Supreme Court handed down a series of 6-3 decisions last year that aligned with Republican Party positions on guns, religion and abortion, public opinion polls showed trust in the court nosedived, at least among Democrats.

"She really did try to find the center of American politics and reach compromises," said Eric Segall, a law professor at Georgia State University. "And that's what we're missing today."

O'Connor, the first woman to serve on the Supreme Court, died Friday in Phoenix from complications related to advanced dementia and a respiratory illness. Nominated by President Ronald Reagan in 1981, she served nearly a quarter century before retiring in 2006 − emerging as a key swing vote in some of the most important issues to come before the Supreme Court.

"Justice O'Connor was viewed as a conservative, especially in her early years on the court. But she always was searching for consensus and moderation," said Stewart Schwab, a professor at Cornell Law School who clerked for O'Connor in the 1982 term. "Even from the beginning, she was concerned about the practical impact of the court’s rulings and sympathized with those whom the law treated harshly."

Schwab acknowledged that, since her departure, the court "has turned more conservative and stripped away many of her key rulings." But, he said, "she remains a beacon of pragmatic, centrist judicial decision-making."

O'Connor sought compromise, even on abortion

In Roe v. Wade, a 7-2 majority established a constitutional right to abortion in 1973 and allowed people to exercise that right until the end of the second trimester. Nineteen years later, O'Connor was central to a decision in a case called Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which ended the trimester framework and allowed people to obtain an abortion until viability – the point when a fetus can survive outside the womb, or about 24 weeks into a pregnancy.

"Each generation must learn anew that the Constitution's written terms embody ideas and aspirations that must survive more ages than one," read the opinion, which O'Connor co-wrote. "We accept our responsibility not to retreat from interpreting the full meaning of the covenant in light of all of our precedents."

Last year, a 5-4 majority harshly criticized both Roe and Casey and jettisoned them, returning the issue of abortion to the states in the watershed Dobbs ruling. That opinion was written by Justice Samuel Alito, who President George W. Bush nominated to replace O'Connor.

"Far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division," Alito wrote last year.

Supreme Court knocks down affirmative action

O'Connor wrote the opinion for a 5-4 majority in 2003 that found the University of Michigan Law School did not violate the 14th Amendment by considering race in its admissions process. That landmark opinion also raised a caveat of sorts for critics of race-conscious admissions, explaining that the justices expected that "25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today."

Though the Supreme Court didn't explicitly overturn the Grutter v. Bollinger decision last year, little remains of it.

Voting along ideological lines, the court ruled that the admissions procedures used by Harvard College and the University of North Carolina − procedures that closely followed the Grutter precedent − violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The schools, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, "have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin."

Anup Malani, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who clerked for O'Connor in the 2001 term, noted that the 25-year horizon the justice included in her opinion demonstrated that she had reservations with race-conscious admissions. He also speculated that O'Connor may have had concerns with the claims of discrimination against Asian American applicants that were raised in the recent cases.

"Why do we have these possible reversals? The answer is clearly the 6-3 split," Malani said.

"With a 5-4 split like you had even after she stepped down, the left-most Republican appointee would become a swing vote that would hold the middle," he said. "But everyone to right of Roberts is pretty right."

That may change with Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Malani said, but it hasn't yet.

'A lot of her work dismantled'

The point was not lost on Amanda van Arcken, a 48-year-old Oregonian who felt compelled to stand outside the Supreme Court on Friday after learning of O'Connor's death.

“She's a pioneer when it comes to being a woman and working the position that she did,” van Arcken said. “Unfortunately, she lived just long enough to see a lot of her work dismantled.”O'Connor was the nation's first woman justice, van Arcken noted. And so it was especially painful, she said, to know that the overturning of some of her best-known decisions had an especially profound impact on women."I was just kind of reminiscing about that and wondering how that felt to her," van Arcken said. "I think it's terrible."

Contributing: Cybele Mayes-Osterman

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Sandra Day O'Connor: Supreme Court's right turn has eroded her impact