After Sandusky scandal, Penn State made reforms. The system has been unraveling ever since

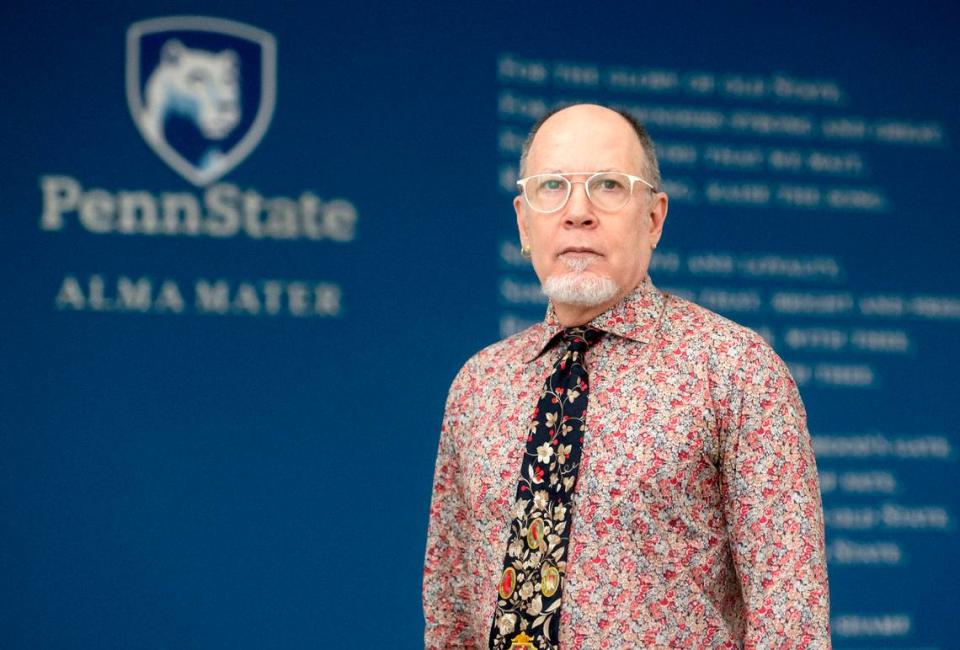

John Champagne submitted his report just before noon on Oct. 28, 2021. The many hours of compliance training the English professor had taken during his nearly 30 years at Penn State Behrend had sunk in.

He understood that reporting misconduct was his duty.

Within seconds of pressing send, Champagne was notified that Penn State’s Office of Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response had received his report, which alleged that an upcoming “Pray the Gay Away” event on University Park’s campus created a “hostile work environment.” At least 11 university administrators were also sent copies of the claim, Champagne was told.

The professor’s complaint had entered Penn State’s internal accountability system — a series of compliance and risk management offices, many of which were formed in the wake of the Jerry Sandusky child sex abuse scandal roughly a decade earlier.

Penn State was applauded as a national leader for these reforms and pledged to “never waver” from its commitments to safeguarding children, students and employees.

“The news about the positive change is abundant here at the university,” a senior official told the university’s Board of Trustees in 2015 about the changes. “It’s something that we all can, and should, take considerable pride in. And we are not resting on any laurels.”

Not long after those comments, though, the system began to unravel. A yearlong investigation by Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times found the internal accountability apparatus Penn State constructed has repeatedly failed those it was intended to protect.

A decade after the national scandal, Penn State lacks a unified way to track all cases of reported misconduct. Its various compliance offices do not all follow a standardized investigative protocol and do not disclose their findings to the public or to the wider university community. This decentralized structure results in multiple offices applying policies to more than 123,000 students and employees on two dozen campuses across the state with a limited awareness of existing problems — a setup so gnarled it snared Penn State’s signature ethics hub.

Penn State built an office to uphold its ethical standards and structured positions to “ensure accountability for senior administrators.” Yet for nearly two years, that unit struggled to handle behavior it was designed to prevent — the chief ethics officer was repeatedly accused of misconduct and retaliation; people complained Penn State’s hotline reporting process was unfair and subjective; a university leader was accused of interfering with investigations of top administrators; and the unit allegedly stopped providing oversight of other investigative offices.

Federal and state inquiries have found failures in the university’s systems for years despite Penn State’s Board of Trustees creating committees to oversee risk and compliance. Problems identified during the Sandusky scandal remain, a U.S. Department of Education report from 2020 concluded, noting that there are “serious inadequacies” in how Penn State handles claims of sexual harassment.

Four years after Penn State created a special position to protect children in university youth programs, a state report found the university was not properly vetting all individuals who had contact with children, and that potentially dozens of youth camps were operating with at least one individual lacking proper background checks.

In the wake of the national scandal, the university said it would emphasize and enforce its anti-retaliation policy to encourage whistleblowing. But a 2017 survey found that less than half of Penn State employees believe Penn State does not retaliate against people who report wrongdoing.

Other possible windows into whether Penn State is living up to its promises are opaque. Information about the effectiveness of its ethics office is delivered to university leaders behind closed doors. The legal requirements of transparency to which Penn State’s academic peers are held are largely nonexistent in Happy Valley, the result of a special carveout from Pennsylvania’s open records law.

Penn State said it encourages misconduct reporting even if people are unsure there is a violation, and its policy is to respond to all reports of “potential sexual or gender-based harassment or misconduct in a manner that is timely, supportive, and fair.”

Champagne received a response to his report a year and a half later, a delay that made him question whether complaints are truly given any priority, especially ones more complex than his.

“I assumed that there actually was a system that worked for reporting this kind of stuff,” Champagne told Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times.

In a statement in response to this investigation, Penn State said it examines its practices and makes necessary changes.

“As a predominantly decentralized, large and complex organization, the university’s mechanisms for responding to reports of wrongdoing and reporting on outcomes of the university’s handling of such reports have grown organically throughout its history as needs have been identified,” the university said. “Following internal and external examinations and audits of the university’s previous practices, new policies, protocols and people have been put into place.”

The university has not announced a timeline for a universitywide system for tracking reports of wrongdoing. President Neeli Bendapudi included creating such a system in her diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging plan announced this spring without specifying when it would be implemented.

A 2020 statement from an assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Education, which documented Penn State’s failures in handling sexual misconduct cases in a 2020 report, echoes more than three years later: “Given all of the attention that Penn State has faced in the wake of the Jerry Sandusky scandal, it is disappointing that so many serious problems have remained at that university system.”

Trouble in the ethics office

By the summer of 2019, fear and frustration began to boil over in Penn State’s Office of Ethics and Compliance.

At least one person was so desperate for help that they appealed directly to then-President Eric Barron.

In an email to Barron, the anonymous reporter said the university’s top ethics officer, Kenya Mann Faulkner, was ridiculing staff within her office in group settings, including calling them names and mocking their physical appearances.

Penn State officials had investigated the matter months earlier, the anonymous reporter said, but the situation did not improve. Office morale was deteriorating. Fear of retaliation was discouraging some employees from speaking out, while others, the email read, “expressed a reluctance to do so again given the administration’s apparent tolerance of such conduct.”

“These conditions may soon, if they haven’t already, raise concerns in the larger Penn State community that the university is either not interested in, or able to, address such conduct when it is reported,” the tipster said.

Created in 2013, the Office of Ethics and Compliance handles some internal investigations, oversees systemwide ethics training, and manages the university’s misconduct hotline. The unit, which reports directly to the Board of Trustees’ legal and compliance committee, was positioned as a centerpiece of Penn State’s post-Sandusky reforms.

A former FBI special agent and white-collar crime investigator initially led the office. The Chronicle of Higher Education heralded the unit as Penn State’s push to “put ethics at the center of everything they do.”

Faulkner, whose experience included a series of compliance-related jobs, began as Penn State’s chief ethics and compliance officer in December 2018. Within months, allegations of discrimination and misconduct sparked an internal investigation of her office, according to court filings. Faulkner remained in her role.

In July 2019, the same month Penn State’s president was contacted, the ethics office received an official hotline complaint with similar allegations against Faulkner, according to a copy of the complaint reviewed by Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times.

Typically, an ethics office employee reviews a complaint and shepherds it to the correct oversight unit, though ethics office employees sometimes assist or lead investigations.

But this complaint was about the chief ethics officer.

Three days later, another hotline report arrived. This one accused ethics office employees of creating a hostile work environment for Faulkner, according to a copy reviewed by Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times.

The dueling complaints gave the university a chance to show its commitment to accountability. Instead, the situation marked a step backward.

Penn State hired an attorney with the private law firm Duane Morris to investigate the office and provide legal advice to the university, according to an email shared with Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times.

The firm previously represented Penn State in high-profile cases such as the Sandusky scandal and the 2017 hazing death of a student.

Two months after the complaints, David Gray, then-senior vice president for finance and business, told ethics staff that the investigation did not find “new behavior.” Gray, who retired from Penn State in August 2020, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Gray, according to court filings and former employees, told the staff they needed to “hit the reset button.”

‘How many more need to leave’

In January 2020, several months after the “reset button” meeting, Penn State’s ethics office received another hotline complaint accusing Faulkner of misconduct. In February, the hotline operator told the anonymous reporter the matter was referred to human resources and an “inherent conflict of interest” meant the ethics office could not provide updates about the report through the hotline’s secure messaging system.

In March, the operator suggested the anonymous reporter contact a senior human resources official to discuss the allegations. When the reporter demurred, asserting a desire to remain anonymous, the hotline worker suggested the tipster create an email account “such as Gmail” because the “ability to effectively respond to this or any hotline complaint is often dictated by the level of information received.”

Greg Triguba, an attorney with expertise in corporate compliance and ethics, told Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times that organizations often use independent, third-party hotline services to encourage reporting and protect against retaliation. When the person designated to oversee complaints is named or implicated in a complaint, the hotline should route such reports to another individual or office, he said.

“It would never be a good practice to recommend to a reporter that they go outside the established reporting mechanism channel for communicating to the organization by creating a free email account such as Gmail and others,” he wrote in a statement. “Among other things, there are information security, privacy, and confidentiality risks associated with using such platforms, and it undermines the value of the existing reporting mechanism that the organization has in place.”

In a statement, Penn State defended its actions, saying allegations of misconduct within the Office of Ethics and Compliance were once routed to the vice president for finance and business but are now sent to the university’s lawyers. Multiple offices can receive reports of potential misconduct, Penn State said, and “there also are mechanisms in place to protect confidentiality when a staff or faculty member makes a report about their supervisor or management.”

Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times, after reviewing the office’s staff pages on the Internet Archive, estimated that at least eight people left the unit in two years under Faulkner’s leadership.

The final message the anonymous reporter sent to the ethics office was a question presented as a statement: “How many more need to leave before someone will help them.”

One former ethics employee who was allegedly forced out took the university to court. In a 2022 lawsuit, Denise Shivery, a former compliance specialist who taught new employees how to flag misconduct and what protections exist against retaliation, claimed she was fired in June 2020 for reporting Faulkner’s alleged behavior.

After she first complained about Faulkner in 2019, according to the court filings, Shivery said she was subjected to a pattern of retaliation in which she was slowly stripped of her job duties and passed over for promotions.

In the aftermath of the firing, internal documents obtained by the newsrooms show Penn State again called in Duane Morris to investigate the ethics office. The results of the firm’s findings were never disclosed. Faulkner remained in charge.

In her 2022 lawsuit, Shivery said Penn State never interviewed her during this investigation. In its legal response, Penn State said it had “discussions with various individuals” and that the “substance of (Shivery’s) allegations were adequately conveyed.”

Penn State denied retaliating against Shivery but settled the case out of court in January 2023. The details of that settlement are confidential.

Faulkner speaks out

In September 2020, the ethics office received a third hotline complaint alleging misconduct by Faulkner. The complaint, obtained by Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times, said employees were leaving the office and contained additional detailed allegations of retaliation and workplace misconduct by Faulkner.

The complaint also claimed that Faulkner stopped the ethics office from tracking cases handled by other departments overseeing complaints of racial and sexual discrimination.”

According to the third hotline complaint, this decision to stop the oversight, which kept the ethics office in the loop with Penn State’s other investigative units, resulted in “severing a strong partnership and compliance monitoring opportunity and exposing the University to potential liability and risk of noncompliance.”

Penn State told Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times that the university does not have a centralized system to track all cases of reported misconduct across various offices.

The third complaint also underscored the inconsistency with which the ethics office handled reports. The employee who received it did not cite a conflict of interest, as had been the case with a previous complaint.

After notifying the anonymous reporter that the matter was “under review,” the office did not respond for several months.

Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times sent Faulkner a detailed list of findings via email to learn her perspective on her time at Penn State. Reached later by phone, Faulkner declined to comment.

After Faulkner learned about the latest hotline complaint against her, she sent an email in October 2020 to top Penn State officials, including then-President Barron and then-Provost Nick Jones. Faulkner claimed she was the target of harassment by former employees of her office.

In the email, a copy of which was obtained by the newsrooms, Faulkner said she was treated differently because she is African American.

Faulkner also alleged that, at the direction of a university leader, she did not investigate multiple misconduct reports against other top Penn State administrators. Faulkner included limited details in her message about the severity of the allegations against the other administrators, though she wrote that some were investigated by outside counsel.

“I literally cringe when I hear people talk about the Penn State Values,” Faulkner wrote, before she demanded that Penn State stop all investigations into her and that the university contact her former employees to reprimand them.

Barron and Jones, reached individually by email, declined to comment on Faulkner’s allegations. Penn State, in a statement to Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times, declined to address Faulkner’s claims out of “respect of individual privacy interests and consistent with best practices.”

Two weeks before Christmas 2020, a tipster sent a copy of the September complaint to prominent Penn State trustees Matthew Schuyler, the board’s chair, and Mark Dambly, a former chair. The unsigned email, obtained by Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times, noted the previous complaints and investigations involving Faulkner.

“Multiple attempts by various professionals using established chains of command and reporting mechanisms have been dismissed,” the email read.

The Board of Trustees declined a request by the newsrooms to comment on the email to its leaders, citing confidentiality.

The ethics office contacted the third anonymous reporter in late January 2021, nearly three months after its initial response. Penn State’s vice president for administration — a position then held by Frank Guadagnino — “would like to meet with you to discuss this matter personally,” the message read.

The anonymous reporter declined, arguing the initial complaint included detailed information, including names of people the office could speak with for corroboration, about the allegations. The tipster then bristled at being asked to reveal themselves.

“A detailed anonymous report was submitted expressing and describing an environment of bullying and illegal retaliation, enabled by the very administration now asking for the reporter’s identity,” the person wrote back. “What a headline.”

In its statement to Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times, Penn State said the university typically asks anonymous reporters for more information about their complaints. “Such outreach was made in this case but the individual who made this report declined this invitation,” the university said.

Faulkner left Penn State in early 2021. Her exit was announced suddenly, ethics staff told Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times, and followed a prior communication from the university saying she would be on sick leave for a week.

The university reached out to the anonymous reporter in April 2021, more than two months after the last correspondence, to say that Faulkner was gone.

“We consider this matter to be closed.”

A pattern of secrecy

Despite its commitments in the wake of high-profile scandals, Penn State sometimes defaults to patterns of secrecy that perpetuate problems rather than resolve them.

In 2014, two years after Jerry Sandusky was sentenced, more than a dozen women’s hockey players voiced complaints to an athletics official about their head coach’s “mentally and emotionally abusive” treatment, according to reports from The Daily Collegian, Penn State’s independent student newspaper. The student-athletes asked to remain anonymous to avoid retaliation, but a player said their names were instead released to the head coach.

Seven players were cut before the season, although the university said it was not aware of any policy violations connected to the matter. Josh Brandwene, the coach, kept the role until retiring in 2017. In a written statement earlier this month, Brandwene said, “I was twice cleared by Penn State, which the athletic administration promised to announce publicly, but did not.”

A 2012 special report by Pennsylvania’s auditor general in the wake of the Sandusky scandal concluded that “by all appearances, Penn State has not welcomed governance transparency and, in fact, has impeded it.” A follow-up report five years later found that the university implemented some of the auditor general’s recommendations but problems with board transparency remained.

In late March of this year, the Board of Trustees’ subcommittee on compensation held a public meeting to finalize the contract for the new men’s basketball coach. The meeting lasted less than 80 seconds, and included no mention of the coach’s name. Nor were details of the coach’s contract disclosed, something attorney Craig Staudenmaier believed was likely a violation of the Sunshine Act.

“There are personnel issues they can discuss in an executive session but, in terms of making a final decision, they’re supposed to deliberate in public,” said Staudenmaier, an authority on Pennsylvania’s Right-to-Know Law. “And it seems to me that hiring another coach and paying him or her a certain amount of money would be something you deliberate on and do it in the public and vote on it.”

Penn State’s athletic department later issued details of the basketball coach’s contract, though that is not always the case. Financial terms were never disclosed after wrestling coach Cael Sanderson signed an extension last year, for instance. In a statement to the newsrooms, Penn State said, “Salaries of university employees are considered confidential and disclosed as required by law.”

Similarly, the university faced criticism last August when no deliberation was held for what was later revealed to be a $71,000 pay raise for Sara Thorndike, senior vice president for finance and business/treasurer. No agenda was posted ahead of time, another potential Sunshine Act violation that irked several members of the Penn State community.

In a statement, Penn State said this was “an administrative oversight.” The board later ratified the action publicly.

Transparency issues are also present in the ethics office, which reports to the trustee board’s legal and compliance committee. Only once in the committee’s more than 20 public meetings since 2018 has the office presented data on trends and outcomes of misconduct reports, according to a Spotlight PA and Centre Daily Times review of meeting minutes and publicly available recordings.

Penn State said in a statement that the Office of Ethics and Compliance provides an annual report on its hotline to the trustees’ committee for audit and risk. Yet a similar review by the newsrooms of meeting minutes from that committee’s 25 public meetings since 2018 reveals not a single mention of such a report.

In a follow-up statement, Penn State said these reports are presented to trustees during executive or conference sessions.

The board has been criticized for potentially misusing Pennsylvania’s conference provision in order to meet in secret for more than a decade. Penn State told the newsrooms it complies with the law.

A transparency argument involving the athletics integrity officer is central to an ongoing lawsuit in Dauphin County in which a former football team doctor alleges he was fired for resisting calls from head coach James Franklin to rush injured players back on the field. Penn State successfully blocked its internal investigation about the allegations from becoming public, arguing the report was protected by attorney-client privilege because the athletics integrity officer consulted the university’s general counsel as part of the probe.

Franklin, Penn State, and other defendants were dropped from the suit because legal paperwork was filed three days too late.

The athletics integrity officer mentioned in the case, Robert Boland, told sports business outlet Sportico in April 2022 that, in general, he wished his position was structured to be more transparent. “The do-over I would like is if there was some public reporting of this role,” he said. Boland stepped down from the position in March 2022. The university has not hired a permanent replacement.

Michelle Rodino-Colocino, president of the Penn State chapter of the American Association of University Professors, said the school’s transparency gets “an F-plus,” explaining the plus represents the “frustrating and contradictory” nature of the university.

“You can’t hold people accountable if you don’t know what’s going on,” Rodino-Colocino said. “And it’s a structural problem so it’s not like we can easily address it.”

Limits of the law

Penn State grants little public insight into both its accountability practices and its basic internal processes, actions authorized by a special exemption in Pennsylvania’s open records law.

The law was broadened in 2008 to presume all state and local government records should be public, but several entities, including Penn State, are largely not subject to it.

Former university President Graham Spanier lobbied for the exclusion. During testimony before the General Assembly in 2007, Spanier railed against transparency requirements, saying they could have a negative financial impact on Penn State.

He also said the state as a whole would suffer if schools like Penn State had to be more transparent. “Adding state-related universities to the Right-to-Know law would have serious unintended consequences not in the best interests of the Commonwealth,” Spanier testified at that time. “We worry about the creation of a new and expensive bureaucracy to control and process requests for information, and perhaps extensive and expensive litigation over the law’s meaning and effect.”

The commonwealth’s four quasi-public schools, which receive hundreds of millions of dollars in state funds every year, are not subject to the same openness required of Pennsylvania’s public schools and government agencies. Lincoln University, Temple University, Penn State and the University of Pittsburgh are required to disclose only limited information about their inner workings, including tax forms and the salaries of their 25 highest paid employees.

“From a public access perspective, there is widespread agreement that what we have is insufficient to provide real accountability,” said Melissa Melewsky, media law counsel for the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association, of which the Centre Daily Times and Spotlight PA are members.

Four years after Spanier’s testimony, both Spanier and the university came under fire in 2011 for rejecting public records requests for a copy of a 1998 campus police report tied to allegations made against Sandusky. A Penn State lawyer told CNN it was a state-related institution and not legally obligated to comply because of that 2008 exclusion.

Spanier declined to comment for this story.

Since the Sandusky scandal, multiple state lawmakers from both major parties have supported getting rid of the open-records exclusion for state-related universities — but several pieces of legislation have failed to advance.

An attempt at a similar amendment in 2022 never made it past the relevant committee, but the bill’s primary sponsor, state Rep. Ryan Warner, R-Fayette, said through a spokesperson that he is in discussions with other lawmakers to reintroduce the legislation.

“For the last two years, I have directly asked the heads of all four state(-related) universities about the bill and none of them have committed their support,” Warner said in a written statement. “This lack of support is likely a big reason why (the) bill hasn’t moved in the House or the Senate.

“I don’t understand why it couldn’t be done or who would be against it.”

A spokesperson for state Rep. Scott Conklin, a Democrat that represents the State College area and chairs the House State Government Committee, said Conklin couldn’t discuss the potential legislation without seeing it, but affirmed the lawmaker agrees the state-related schools need to be more transparent.

Pennsylvania’s annual appropriation to Penn State and other state-related universities remains in limbo after a group of House Republicans blocked the passage of the funding bill earlier this month, in part, over concerns about a lack of transparency from the schools.

In a 2017 audit, then-Auditor General Eugene DePasquale recommended Penn State work with lawmakers to be included under the state’s Right-to-Know Law.

“The Pennsylvania legislators themselves voted themselves into the Right-to-Know Law and still exempted the state-relateds,” DePasquale, now a candidate for state attorney general, recently told the Centre Daily Times and Spotlight PA. “I still shake my head at that one.”

Penn State said in a statement that the university is “already subject to and fully complies with” the state’s current open records law.

“The General Assembly developed this law after careful review of how it should specifically apply to state and local agencies, the Legislature, the judiciary and state-related universities,” the university said in a statement. “We will continue to work with the General Assembly to ensure that we are accountable for the taxpayer resources invested in Penn State.”

Lack of faith

In 2013 and 2017, Penn State commissioned surveys of employees’ and students’ feelings about its campus culture and values. The results highlighted widespread distrust in the university’s misconduct reporting system.

The 2013 survey, conducted amid the fallout of the Sandusky scandal, found that 75% of participants who observed misconduct did not report it, and only 53% of respondents who did report misconduct said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the university’s response.

A 2017 version of the survey showed some improvements in people’s awareness of how to report misconduct and their willingness to flag it, compared to 2013. However, the percentage of participants who said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the university’s response to reported misconduct dropped to 42%.

The survey found that 44% of faculty and 42% of staff believe Penn State does not retaliate against people who report wrongdoing, an increase from 35% and 30% in 2013.

Last fall, Penn State launched the “Living Our Values Survey,” a study comparable to the ones conducted in 2013 and 2017. The university originally expected to release the results in May, but said it did not receive the data from its third-party vendor until June. It hopes to release the results this summer.

The Ethics & Compliance Initiative, the company that conducted Penn State’s 2013 and 2017 culture surveys, recommended the university publish “periodic summary reports of disciplinary actions that are taken” to build trust among students and employees. The organization also recommended the school track people who report misconduct over time to ensure they are not retaliated against.

Five years after ECI made those recommendations in its 2018 report, no such system exists.

In a statement to the newsrooms, Penn State said it is working on “an integrated case management system that would encompass cases from all of the individual offices at the university that receive reports of wrongdoing, data from which may be used for a public report in the future.”

In 2021, several faculty members published the results of a survey they conducted that found nearly 3 in 4 Black faculty respondents (73.1%) who experienced racism chose not to report it. Several said they chose silence because they felt nothing would be done about it.

In February, a Penn State student wrote in The Daily Collegian about her decision not to report a sexual assault. “It’s enraging to hear allegations surface, knowing they’ll be shoved under the rug to protect the reputation of the university and the organization,” the student wrote.

Just words on paper

Champagne, the Penn State Behrend professor, waited 18 months for the university to respond to his complaint.

He sent follow-up emails as the days added up. In September, after 11 months without a reply, he messaged the university’s Title IX coordinator and the president’s office.

“I have no faith that any kind of complaint would ever be adequately followed up on, short of a lawsuit,” Champagne told Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times. “Penn State responds very well to threats of lawsuits and actual lawsuits.”

In October, during a Faculty Senate meeting, Champagne questioned Danny Shaha, an assistant vice president in the student affairs office, about the lack of a response. The vice president suggested maybe Champagne’s report was forwarded to a different office. Penn State is working to address “communication gaps” between offices, the vice president said.

The university in April declined to answer questions about Champagne’s case, citing confidentiality even though Champagne signed a release allowing Penn State to comment on the details of his report to the newsrooms.

During a Faculty Senate meeting later that month, Champagne asked President Bendapudi directly about his unanswered complaint. A few days later, Suzanne Adair, the former Title IX coordinator, finally emailed Champagne.

“Although there was no intention not to address your report, I absolutely understand the frustration you’ve shared about not being contacted by my office or others,” Adair wrote in the email, a copy of which was shared with Spotlight PA and the Centre Daily Times.

The university is not living up to its principles, Champagne said in an interview. Experiences like his own send a signal to the wider campus community, he added, explaining the lack of action makes the policies just words on paper.

“My sense is that there is no internal accountability whatsoever,” Champagne said.

This story is a collaboration between Spotlight PA State College and the Centre Daily Times.