Sarasota’s first mayor saw nearly a century of change | Sarasota History, Jeff LaHurd

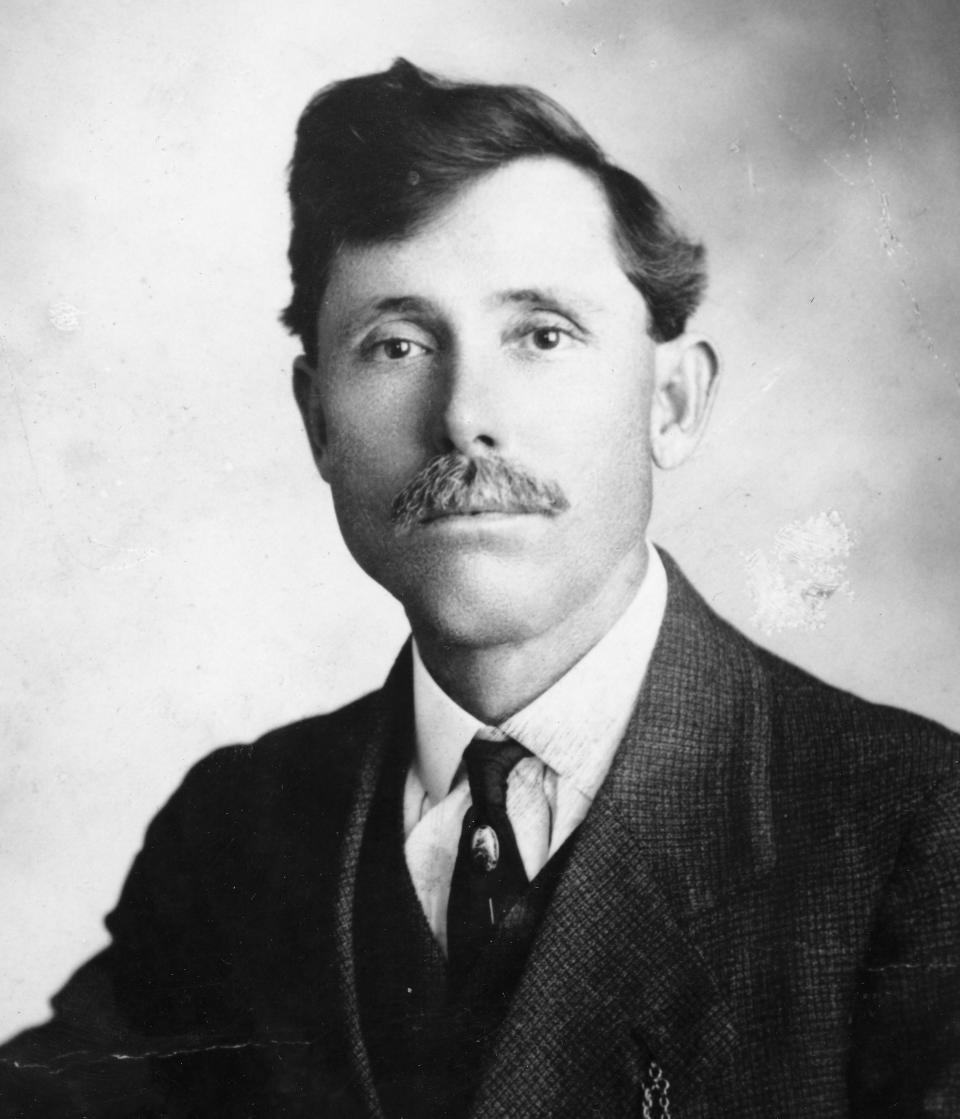

If ever there was a self-taught (he spent nine months in a classroom), self-made man, Arthur B. Edwards was he. Born on Oct. 2, 1874, in a log cabin on what today would be the northern county line dividing Sarasota from Manatee near the airport, his was an Horatio Alger story.

The cards for success in life were stacked against him. His parents died when he was 14, leaving him with three younger siblings to provide for in a harsh wilderness, inhabited by pioneer settlers who were scattered around the area.

As a young man he worked for $6 a month plus room and board in the orange groves. He moved on to five laborious years as a cowhand, until he sought and was given an assignment as a civilian in the Quartermaster’s Department stationed in Havana during the Spanish American War.

The origins and the first edition of the Herald-Tribune

In 1885, an eleven-year-old Edwards was trailing his father through the woods hunting for game when they happened upon a surveying crew camped at today’s Five Points.

They stopped their hunting expedition to watch the unusual goings-on. The surveyors were busy at work platting the town of Sarasota for the Florida Mortgage and Investment Company, a Scottish land syndicate based in Edinburgh which had purchased 50,000 acres for their countrymen to colonize.

Many years later, Edwards described the encounter. Upon seeing father and son observing them, the chief engineer of the crew announced grandly: “We will lay out the town of Sarasota from this hub.” A stake was driven in the center of Five Points from which to the crew began taking readings. Five Points is still considered the heart of Sarasota, and interestingly this was the site for our first roundabout, albeit a rudimentary one.

Edwards described his youthful Sarasota environment as “a tropical wilderness among the thistles, Spanish bayonets, briars and thorn trees.” The harsh reality of his life in those pioneer days included swarms of mosquitoes, wild animals including panthers, bears and hogs, and the necessity to hunt and fish for their food.

On the plus side of that bleak scenario, he fondly recounted an area rich in nature’s bounty: “The hollow trees were full of honey; the woods with game; the water, both fresh and salt, were teaming with seafood – oysters, scallops and clams; the jungles and forests full of edible tropical fruits and berries ... fertile soil for vegetables, sweet potatoes, Indian corn, sugar cane ...”

The Scot Colony, which came ashore on Sarasota Bay, was ill prepared for the wilds that greeted them, and bitter from the experience, and soon disbanded. But the mortgage company had 50,000 acres of land to sell and sent John Hamilton Gillespie, son of the syndicate’s president, to revive the effort.

Streets were grubbed, a hotel was constructed, boarding houses and homes were built downtown, the pier at the foot of lower Main Street was improved, trees were planted to beautify the area, businesses appeared – and the former wilderness slowly began to evolve into a habitable community.

A giant step forward for the Sarasota Bay district occurred in 1902 when the Seaboard Airline Railway Company announced it was going to lay tracks to Sarasota. That promising news encouraged the citizens to vote to incorporate.

Early on, Edwards, who possessed an innate love for Sarasota immediately saw the potential for train transportation to attract newcomers. In 1903 he opened Sarasota’s first real estate and insurance office and continued in the business until 1964 when he retired at 90 years of age.

To spread the word about Sarasota, he convinced train companies throughout the nation to send him the names of those who expressed interest in Florida. Many inquiries were received, and Edwards wrote a letter to each prospective buyer extolling Sarasota’s assets – its beauty, climate, beaches, fishing, hunting and farming potential.

In 1910, Edwards teamed with local landowner and developer J.H. Lord to induce wealthy Chicago socialite Bertha Palmer to come have a look-see at the growing community.

Edwards, who knew the area better than anyone, escorted her around in his horse and buggy. She loved the area, saw its potential and bought thousands of acres. The Oaks at Osprey became her winter home. Enticing Mrs. Palmer here was a seminal event in the history of Sarasota.

Palmer’s pronouncements about Sarasota’s beauty garnered much publicity in the major newspapers and put the small community on the map. Edwards called the arrival of the Palmer family “the most notable important, outstanding and far-reaching achievement for Sarasota and the whole Sarasota Bay area.”

In 1907 he was appointed by Governor Hardee as the town’s first tax assessor. Tasked with writing the first tax books, he served in that position through 1913.

When Sarasota incorporated as a city, he took office as the first mayor on Jan. 1, 1914, and was reelected in 1918, serving until 1920.

He was a founding and active member of both the Board of Trade, which morphed into the Chamber of Commerce, and the Kiwanis Club. Both groups were strong advocates for Sarasota’s development and growth, and when the 1920s real estate boom struck, Edwards, through his real estate firm, was poised to capitalize on the ensuing buying frenzy.

He forged a reputation for his honest and above-board dealings, saying that shortly before he died, his father left him with advice he followed throughout his life: “Always be in good company; be honest and truthful; work hard and save your money; also retain your self-respect and others will respect you.” That philosophy kept him at the forefront of his beloved Sarasota’s leadership.

Of the freewheeling 1920s years, Edwards reckoned that it would have “taken 100 years for the average American city to acquire the same amount of public and private improvements as did Sarasota in that two-and-a-half-year boom period.”

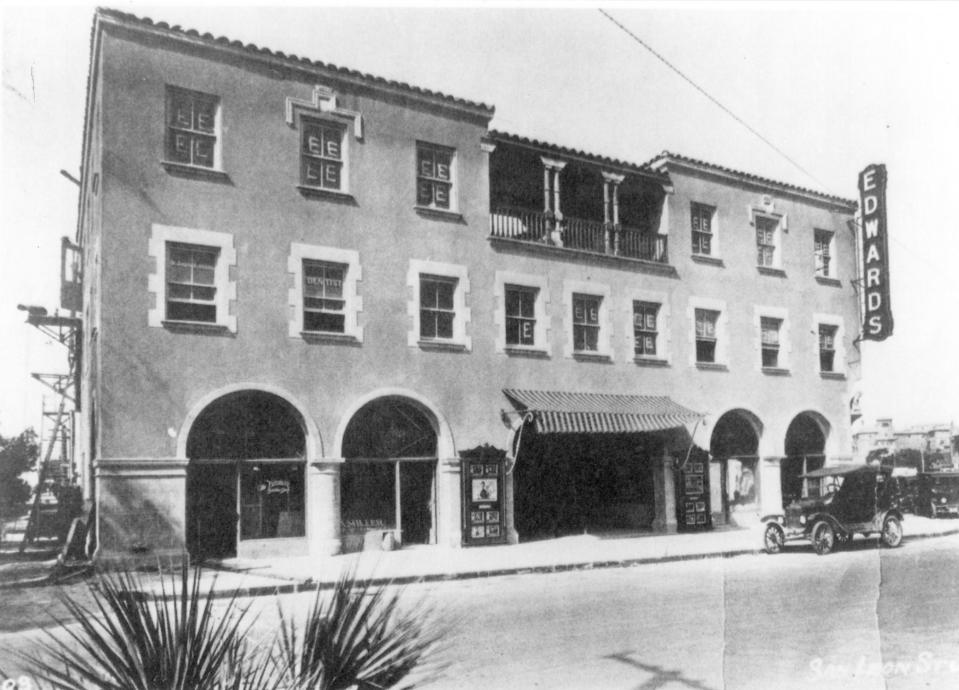

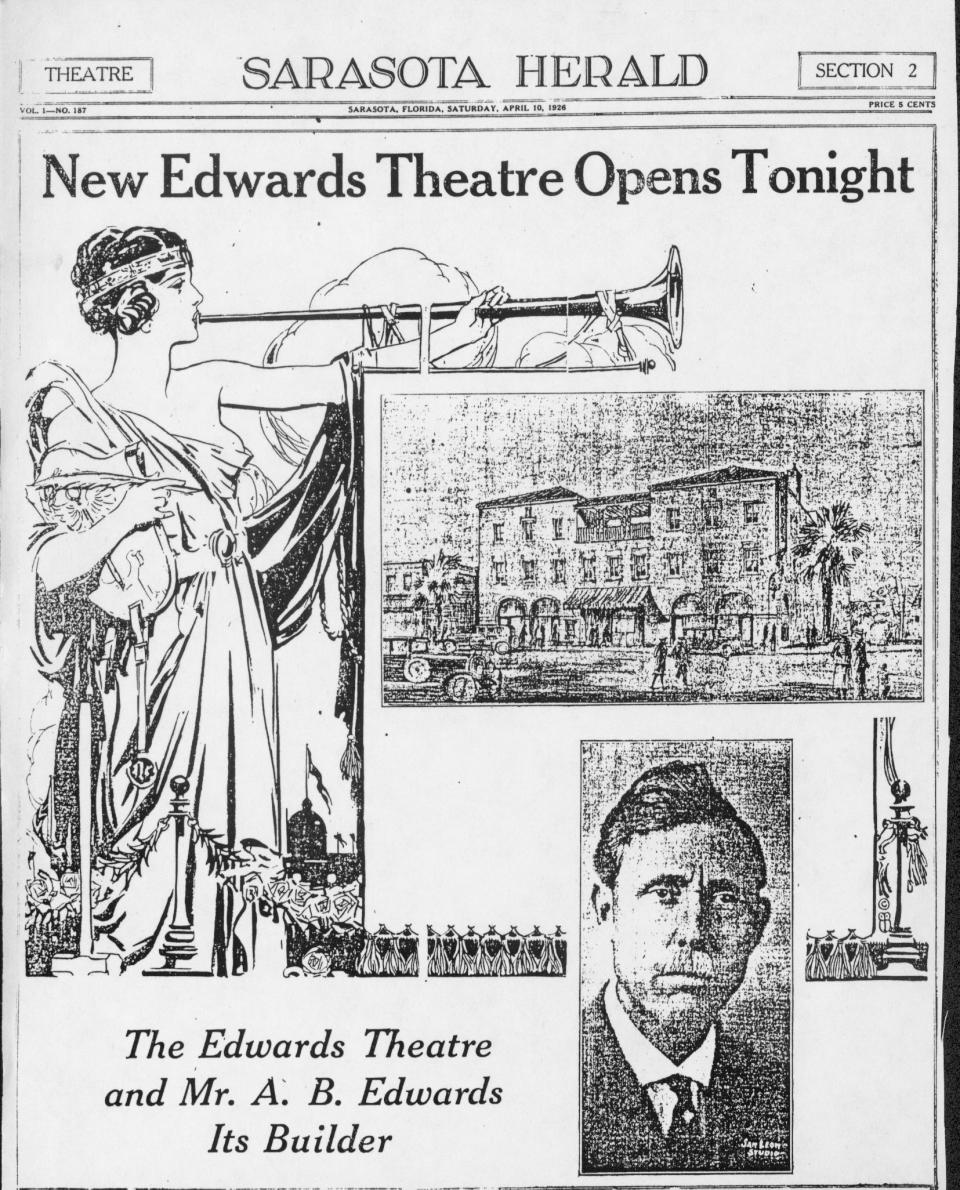

Edwards built the opulent Edwards Theatre, which still draws dolled-up audiences today as the Sarasota Opera House. Opened in 1926, the magnificent, multipurpose Mediterranean Revival building offered live entertainment as well as motion pictures and housed offices, apartments and shops.

Edwards married Fannie Lowe in 1900, and the couple produced four daughters. Their 1926 Siesta Key home was designed by leading architect Dwight James Baum, who had been commissioned to draw the plans for Ca’ d’Zan, the Courthouse, and the El Vernona Hotel, among others. Edwards’ residence was a far cry from the log cabin he was born in – The Herald described it as “Palatial in Appearances.”

The couple were married for 63 years. After the real estate market collapsed, Edwards recalled that the high-pressure salesmen who had been making money hand over fist fell on hard times.

“Then about the latter part of 1926 [they] were trading among themselves wondering what happened; and by early 1927 the big real estate boom was all over. The water had been squeezed out of the sponge and the professional land traders ... had moved out much faster than they came in.”

Edwards remained active throughout the Great Depression, helping to obtain Works Progress Administration money for projects that included the Post Office Building, the Municipal Auditorium, and the Lido Casino.

Always a lover of nature and a man of the great outdoors, he played a major role in the creation of Myakka River State Park, for which he was awarded the American Legion’s Community Service medal. His name is listed on a monument there as one of those who established the park.

His nonstop pursuits included being president of the Sarasota Citrus Growers Association, a member of the Sarasota County Fish and Game Association, the State Fresh Water and Game Conservation Commission and the Florida Board of Forestry and Parks. He was chairman of the advisory council of the Myakka River State Park, and a member of the Sarasota County Historical Commission.

Always an avid advocate for the education he never received, Edwards also helped to establish New College, serving as chairman of the New College Site Committee.

A.B., as he was affectionately called, died at his home on Nov. 14, 1969. He was 95, and appropriately known throughout the city he loved as “Mr. Sarasota.”

If A.B. Edwards did not see it all, he saw most of it. As he told Sarasota historian Dottie Davis, “I never came to Sarasota. Sarasota came to me.”

Jeff LaHurd was raised in Sarasota and is an award-winning historian.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Sarasota’s first mayor and first real estate agent put city on the map