Sarasota History With Jeff LaHurd: Golden past, dubious future for Mira Mar Apartments

I believe that newcomers to our much-loved and overdeveloped city are in for a lesson in the irrelevance of historic sites to the Sarasota commission.

It will be an object-lesson in the adage that money talks. Recent residents will soon learn that protestations to the contrary, and there will be some loud voices to be heard, the 100-year-old Mira Mar on Palm Avenue, the building that signaled Sarasota’s entry into the rarified world of snowbird retreats will soon be a heap of rubble.

Carrie Seidman: Saving the Mira Mar Plaza could be start of protecting Sarasota’s past

For longtime citizens, having seen so many historic sites razed, it’s deja vu all over again.

Historically speaking, nothing in Sarasota has been precious enough to keep the bulldozers at bay.

Not only Spanish Mission, Mediterranean Revival and Sarasota School of Architecture homes that must be leveled because they stand in the way of McMansions, but also significant structures that have achieved iconic status.

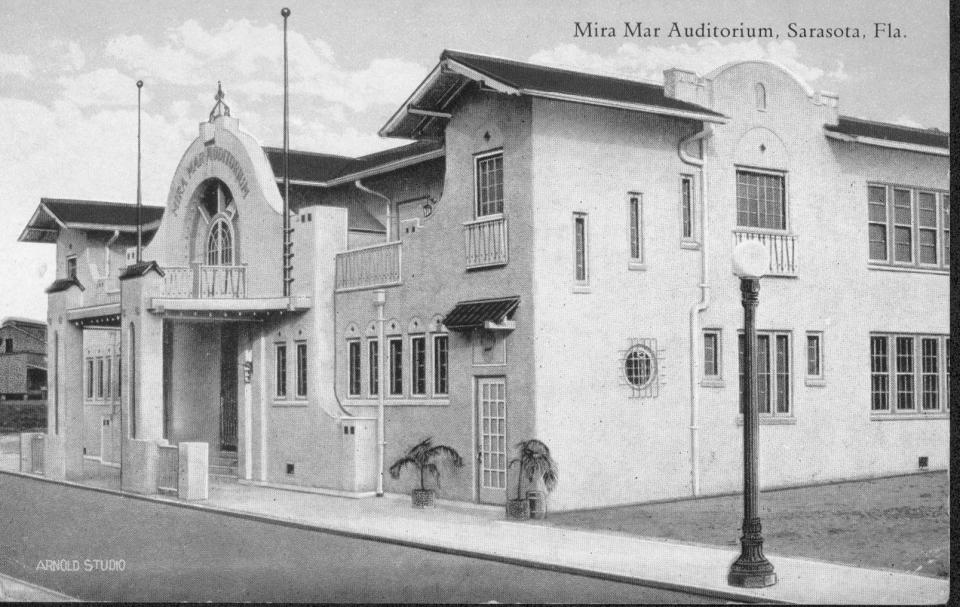

Here are a few in no particular order: The Lido Casino, the Atlantic Coastline Railway Station, the Seaboard Airline Railway Station, the John Ringling Towers (there were howls when that went down), the Mira Mar Hotel, the Mira Mar Auditorium (both, interestingly, now parking lots) the Hover Arcade/City Hall building, the south side of lower Main Street from Five Points to Palm Avenue (also, initially for a parking lot), the McClellan Park School, the DeMarcay Hotel (big deal, they saved the façade).

I could name more; the list is long and varied. Having in common only that taken together, they defined a Sarasota that exists only in the memories of those who were on the scene during those, really, best of times.

More Sarasota history

Hover Arcade was high point of Sarasota bayfront development

From fruits to U.S. Presidents: How Sarasota streets got their names

The Mira Mar’s destruction is not a done deal yet, so for the sake of argument, here is why it is historic enough, even for Sarasota, to be left alone.

Sarasota really needed Andrew McAnsh. Progressive citizens knew it, the City Council knew it, the Chamber of Commerce knew it, indeed, McAnsh knew it.

The city was desperate for a world-class, luxury hotel to move forward as a destination for monied snowbirds who would “Spend Their Summer This Winter In Sarasota,” as the era’s catchphrase put it.

Sarasota’s natural beauty was not sufficient to draw rich northerners. Suitable accommodations were a must. Which is why McAnsh’s upscale lodging could ask for and obtain “valuable concessions” – free water, free electricity and no taxes on the property for 10 years.

It was hoped the generosity of the council would attract other capitalist developers to invest in Sarasota.

It was not the first promise for high-class accommodations. On April 23, 1914, The Sarasota Times reported that developer Owen Burns, Sarasota’s largest landowner, was going to construct a 100-room hotel on his Sunset Park property.

Designed and furnished to “attract the luxury-loving class of tourists, every inducement will be offered to have them linger contentedly ...” Assurances guaranteed that work on the stone and brick structure would begin within 30 days.

Burns and his architect, Harold N. Hall, inspected Henry Plant’s hotel, Belle View in Bellaire, and scouted out the Gasparilla Inn on Boca Grande for ideas.

The Times reminded, “Lack of up-to-date accommodations for wealthy tourists who come here every winter to escape the cold ... has been felt for years and the new structure will meet this long felt want in every respect.”

(A few years later, before McAnsh arrived, Burns tried to interest John Ringling to undertake a similar hotel venture. On behalf of the City Council, Burns wired Ringling that the council would give him free light, water and no taxes on the hotel for ten years if Ringling would construct a $300,000 hotel along with a park that would be open to the public. Ringling demurred and later, McAnsh took the same deal.)

McAnsh, whose financial and development bona fides were beyond reproach, was heralded as a town builder, an asset to any city in which he chose to develop.

The Sarasota County Times was four-square behind the McAnsh project, writing that a modern hotel on the bayfront was an asset the city had long needed and would increase property values throughout the area.

Why invest and build in Sarasota rather than much larger cities like St. Petersburg, Miami, Palm Beach or any number of more established areas? It was not about money. McAnsh assured the Times he already possessed all the money he needed.

He was drawn here to invest by the beauty of Sarasota Bay (as had Bertha Palmer), and the surrounding area, adding, “To know Sarasota and its people is to love both. No more cordial people could be found anywhere. That is how I feel about it.”

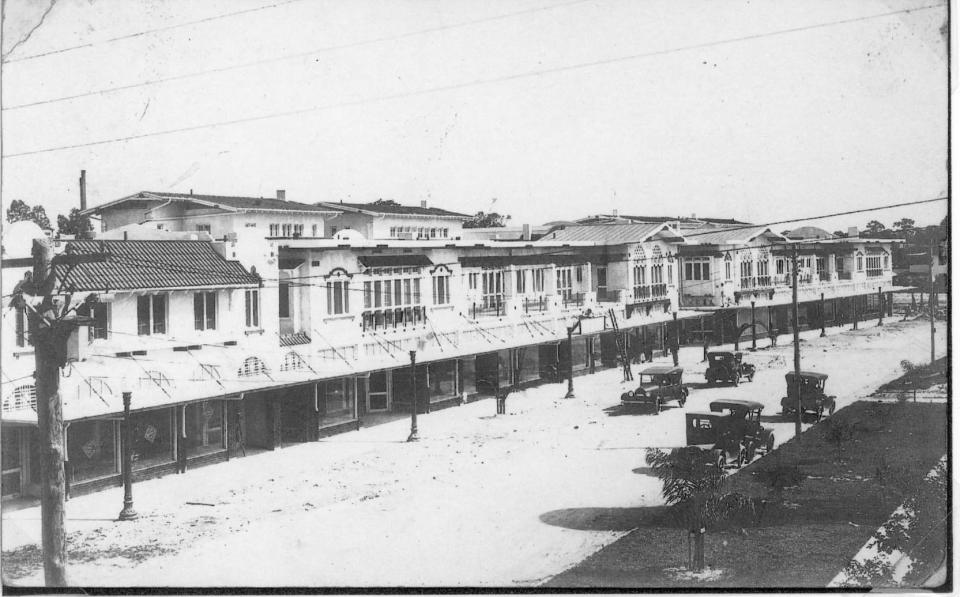

On Sept. 14, 1922, the front page of The Sarasota County Times bore an architect rendering called the Tamiami Inn, touted as a million-dollar hotel. It would be preceded by luxury apartments fronting Palm Avenue, offering an unobstructed view of Sarasota Bay.

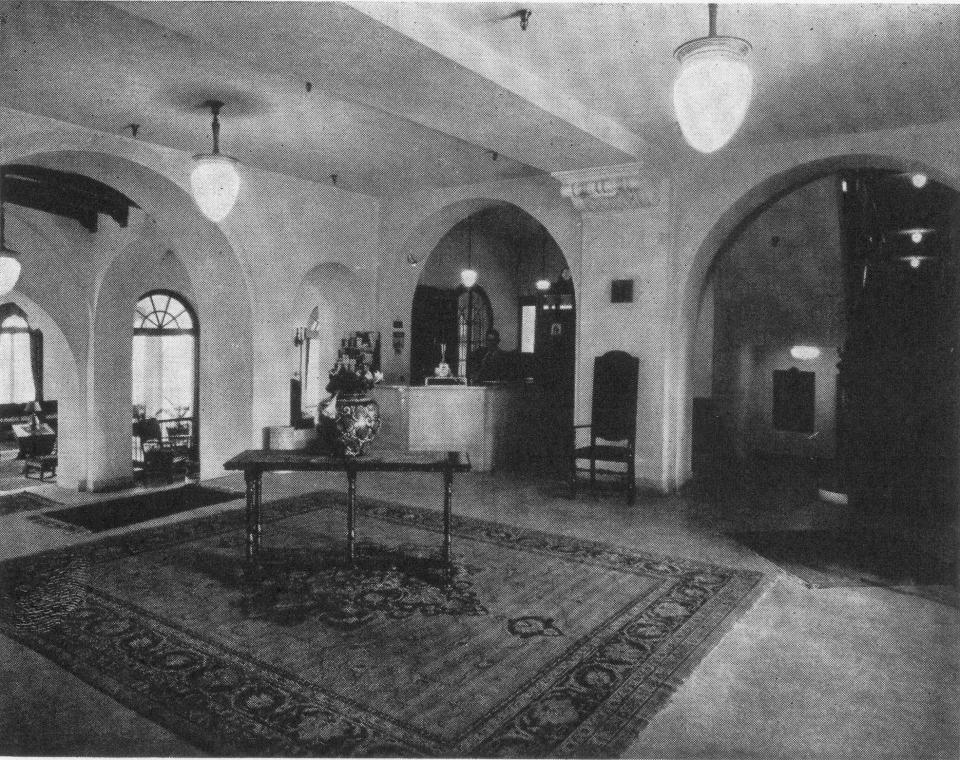

Later the name was changed to the Mira Mar, Spanish for Sea View, and advertised as “The Gem of the West Coast”, and Mira Mar apartments, “Florida’s Wonder Apartments.”

Chicago architect William G. Krieg’s plans, and drawings of the much sought-after hotel were put in the window of The Sarasota County Times for all to examine.

When McAnsh returned in November of that year, he was given a hero’s welcome. City leaders met him at the train station in Rubonia and whisked him away to Sarasota where he was paraded along Main Street, led by the Sarasota Band.

Sirens wailed, bells rang out and red fuses were lighted on both sides of the road, “casting a soft glow which lent the scene the effect of a truly gala occasion. The Times called it a “Royal Welcome to City.”

Homes and businesses along the parade route displayed welcoming banners. One proclaimed, “Flagler built the East Coast, McAnsh will build the West Coast. Flagler West Palm Beach; Fisher Miami; McAnsh Sarasota.”

By December 1922, enough of the “$500,000” apartment building, “the largest individual building permit ever issued” had been constructed to offer a preview of its beauty. The paper intoned, this was a sign that “The sleeping giant has awakened and cast aside his swaddling clothes.” Promising it “marked the beginning in the city’s history of a new epoch in development.”

According to The Sarasota Times, in January 1923 the apartments were opened for occupancy, and shortly thereafter it was announced that the W.R. Carman Co. of Tampa and Sarasota had been awarded the contract to build the hotel, which would employ 500 workers all summer.

The hotel was completed in time for the winter season 1923-’24. As the paper correctly put it, “The boom is on and prosperity is here.”

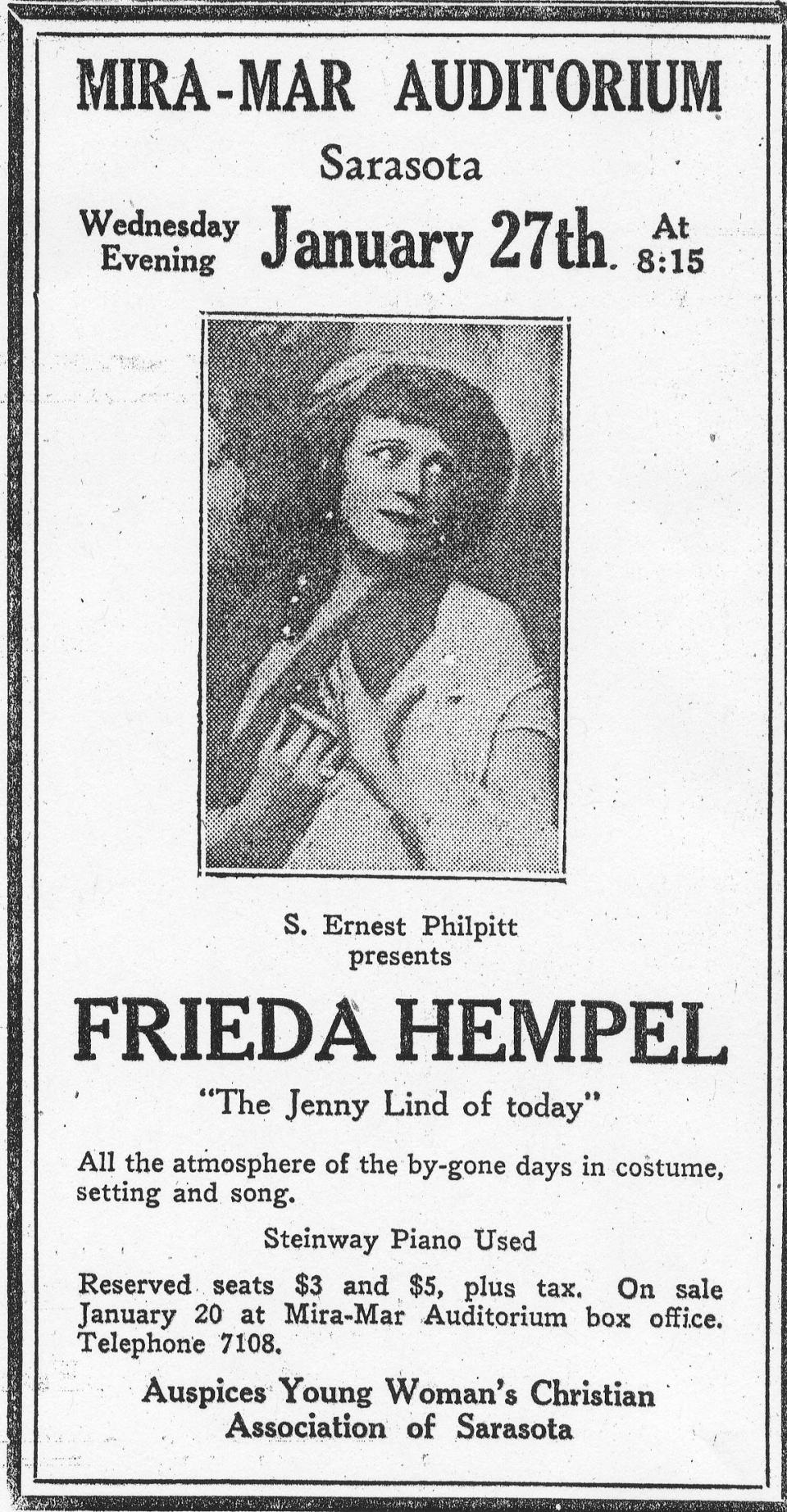

McAnsh was far from finished. On the east coast of Florida, he constructed the beautiful Vera Del Mar Hotel. Shortly after the Mira Mar Hotel was started, he promised to build on property just to the south of it, a recreation casino, dubbed by The Sarasota Times as a “$100,000 Palace Royal which was to have a dance floor for 500 couples, combined with a theatre capable of providing for first-class road attractions and one of the finest bathing pools in the state.” There would be “violet rays for bathers and invalids.”

Architectural drawings were displayed in the window of the Archibald Hardware Co.

The plan for this building was modified to become the Mira Mar Auditorium, sans the pool and violet rays. It did, however, draw major talent and became the go-to gathering place for many local social functions.

(According to Sarasota’s first mayor, A. B. Edwards, upstairs, the auditorium also featured a complete gambling casino operated Conrad & Locke of Chicago. Locals were not allowed to lose their money there; that honor was reserved for snow-birds, many of whom hailed from Chicago.)

McAnsh did considerably more for Sarasota than develop. His connections in Chicago and elsewhere, particularly major-league bankers and businessmen followed him here, generating much publicity about Sarasota’s development potential which fanned the boom.

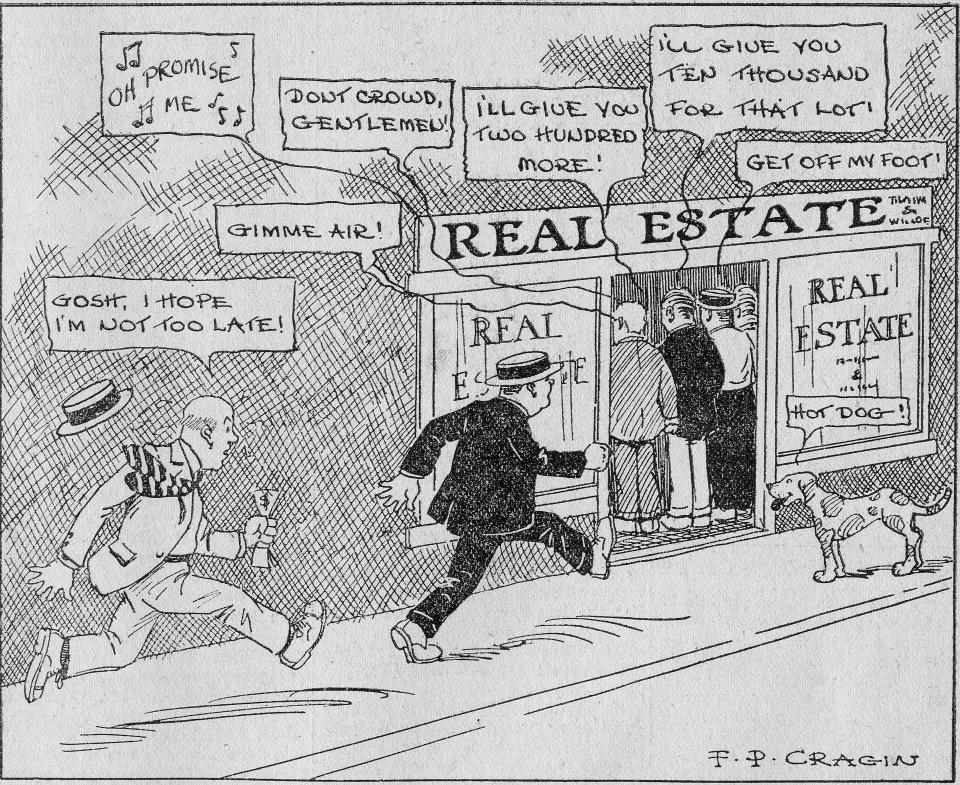

As his projects progressed, the sleepy fishing/agriculture community sprang to life. Throughout the city, real estate sales were reported on the front page of the local papers along with construction of hotels, banks, retail establishments, schools, churches, and everything else needed to become not only a snowbird retreat, but an inviting community.

The front page of The Sarasota Times on May 10, 1923, was crammed with articles illustrating the new real estate reality: “Cummer Buys Mile And A Half of Bay Front From Orendoff,” “Realty Sales Show No Let Up In Past Week, Volume of Activities Continues With Amazing Celerity,” “Mayor Bacon Sells $44,000 Local Property – Seven Sales Yesterday Without Leaving Office,” “Realty Sales Up in Past Week,” “Another Main Street Lot Sold to Alford.” “[Edwards] Closes $150,000 Realty Sales Past Ten Days.” “[A.B. Darling] Buys 84 Acres Of Shore Front Near Englewood.”

Clearly, the fuse to the ’20s era real estate boom was lit by “town builder,” Andrew McAnsh.

The hotel closed in April of 1957 as tourists sought beachfront accommodations.

Enter Charles S. Lavin, known as the “Hilton of the retirement hotel industry.” He owned a string of successful ventures and was dubbed “the answer to the prayers of thousands of low-income retired people caught in the upward spiral of living costs.”

In an article appearing in the Reader’s Digest, his plan was described as “offering inexpensive rates in a hotel setting free of the restrictions encountered in institutions.”

Lavin retired sometime in the 1970s and the hotel fell into disrepair. A group was formed to “re-capture the Splendor.”

Mayor Ron Norman was all for the hotel’s rehabilitation, saying, “I don’t think it’s wise for a community to be stripped of its heritage.”

Others joined in – presaging the failed 1998 fight to save the John Ringling Towers, which used the catchphrase “Return to Splendor.”

But it was all for naught and a photo in the Dec. 30, 1982, issue of the Herald told the story, “From Radiance to Rubble,” showing the backhoes at work.

In the hotel’s place was to be a 17-story twin towers complex which failed to materialize. In the end a parking garage was built on the historic property.

But still intact was the Mira Mar Apartment building, which lit the fuse for Sarasota’s skyrocketing development of the Roaring ’20s. The former lodging was modified to accommodate various businesses, while maintaining the look that had graced Palm Avenue for nearly a century.

Take a picture of it soon. That’s all you’ll have.

Jeff LaHurd was raised in Sarasota and is an award-winning historian.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Jeff LaHurd: Imperiled apartments all that remain of McAnsh’s Mira Mar