Satellites show Antarctic ice shelves have lost 74 trillion tons of water in 25 years

Satellite observations have revealed an alarming loss of ice density at Antarctica's ice shelves over the past quarter century, highlighting the accelerating impact of climate change.

The findings come from 100,000 satellite radar images, mainly from the European Space Agency's (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel-1 and CryoSat satellite missions, which showed that over 40% of these floating shelves of ice have significantly reduced in volume since 1997.

Of the 162 Antarctic ice shelves, 71 had decreased in volume, the study team found. These Antarctic ice shelves lost around 8.3 trillion tons (7.5 trillion metric tons) during the study period, which is an average loss of 330 billion tons (300 billion metric tons) each year.

The extensions of Antarctica's land-based ice sheets act as a barrier, slowing the flow of ice into the ocean and thus, crucially, stabilizing glaciers. That means the region faces a risky "double punch" of shrinking ice shelves and increasingly rapid ice loss in the form of glacier fresh water flowing to the ocean.

The whittling of the ice shelves has released around 74 trillion tons (67 trillion metric tons) of fresh meltwater into the ocean, which could affect ocean circulation. This back-and-forth conveyor belt of water between Earth's equator and poles is crucial in regulating global temperature and serves as a nutrient supply chain for aquatic life.

Related: Climate change hits Antarctica hard, sparking concerns about irreversible tipping

"We tend to think of ice shelves as going through cyclical advances and retreats," study co-author Anna Hogg, an associate professor in the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds in the U.K., said in a statement. "Instead, we are seeing a steady attrition owing to melting and calving. Many of the ice shelves have deteriorated a lot: 48 lost more than 30% of their initial mass over just 25 years. This is further evidence that Antarctica is changing because the climate is warming."

A complex and alarming picture of ice loss

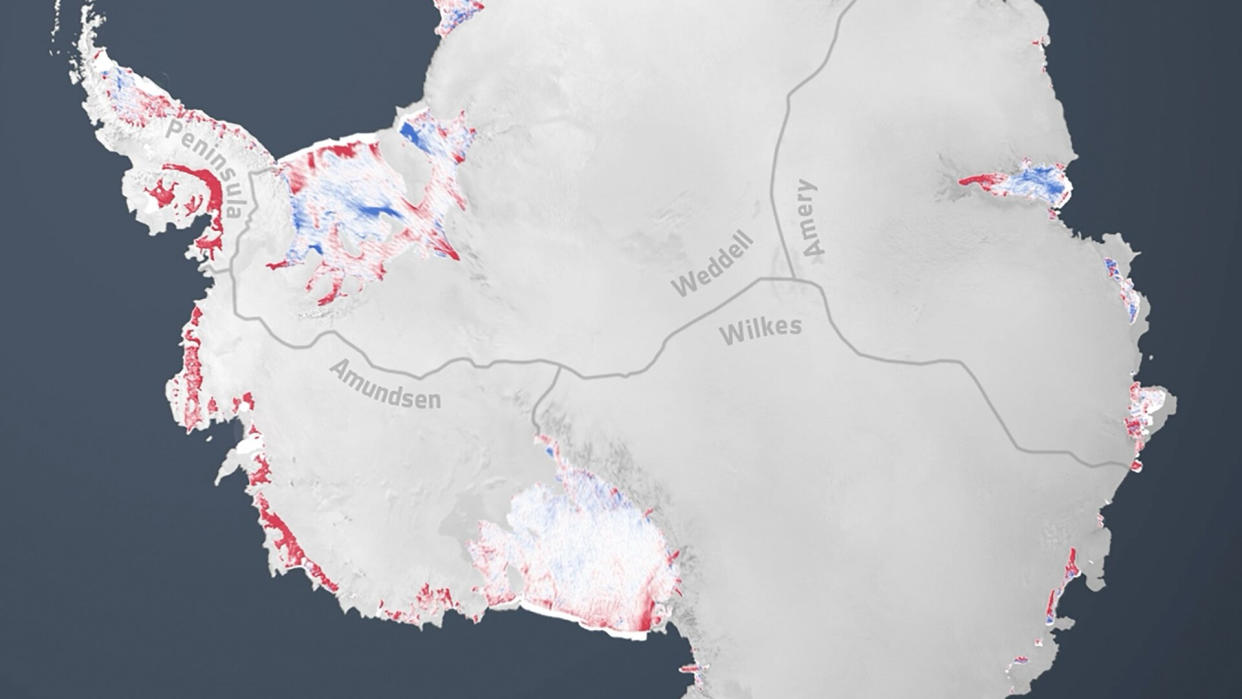

The findings present a complex picture. Antarctica is vast, and the seas on the western side of the continent are subject to different currents and winds than those on the east. This drives warmer water underneath the ice shelves on the western flank. As a result, almost all of the ice shelves on western Antarctica experienced ice loss, while the majority of eastern ice shelves remained intact or even gained mass.

"There is a mixed picture of ice-shelf deterioration, and this has to do with the ocean temperature and ocean currents around Antarctica," study lead author Benjamin Davison, a research fellow at the University of Leeds, said in the statement. 'The western half is exposed to warm water, which can rapidly erode the ice shelves from below, whereas much of East Antarctica is currently protected by a band of cold water at the coast."

The largest ice loss was found at the Getz Ice Shelf, the largest Antarctic ice shelf, which runs for 300 miles (500 kilometers) along the Pacific-Antarctic coastline to the southeast and stretches back 60 miles (97 km) at its widest point. The study found that 2 trillion tons (1.9 trillion metric tons) of ice has been lost from here since 1997, and 5% of that loss was caused by huge slabs of ice breaking away and drifting into the ocean. The remaining 95% of ice loss was the result of melting at the base of the Getz Ice Shelf.

A similar picture developed over the quarter century at the Pine Island Ice Shelf, which buttresses the huge and rapidly melting Pine Island Glacier. The team found this ice shelf had lost 1.4 trillion tons (1.3 trillion metric tons) of ice, with around a third of that the result of ice chunks drifting free into the Amundsen Sea. Two-thirds of the ice loss at the Pine Island Ice Shelf was the result of melting at its base.

The Amery Ice Shelf on the other side of Antarctica gained 1.3 trillion tons (1.2 trillion metric tons) of ice as a result of the cold water, even though the region lost a huge slab of ice when it broke away and drifted into the Weddell Sea in September 2019.

The findings show that Antarctic ice sheets are failing to regenerate under the pressure of a warming climate.

"We expected most ice shelves to go through cycles of rapid but short-lived shrinking, then to regrow slowly,' Davison said. "Instead, we see that almost half of them are shrinking with no sign of recovery."

The work also underscores the importance of satellites like Copernicus Sentinel-1 and CryoSat for monitoring this remote polar landscape during the dark polar winters.

Related Stories:

— NASA searches for climate solutions as global temperatures reach record highs

— Earth is getting hotter at a faster rate despite pledges of government action

— 10 devastating signs of climate change satellites can see from space

CryoSat's "ability to precisely map the erosion of ice shelves by the ocean below enabled this accurate quantification and partitioning of ice shelf loss, but also revealed fascinating details on how this erosion takes place," Mark Drinkwater, head of Earth and mission science at ESA, said in the statement. "Monitoring and tracking climate change across the vast Antarctic continent requires a satellite system that captures data routinely throughout the year. The European Copernicus program's Sentinel-1 satellite mission has fulfilled this need."

Combined with archival data, satellites have helped scientists assess the health of the Antarctic ice sheet.

"In the near future, we will further augment Antarctic monitoring with three new polar-focused missions: CRISTAL [Copernicus Polar Ice and Snow Topography Altimeter], CIMR [Copernicus Imaging Microwave Radiometer] and ROSE-L [Radar Observation System for Europe in L-band]," Drinkwater said.

The study was published Oct. 12 in the journal Science Advances.