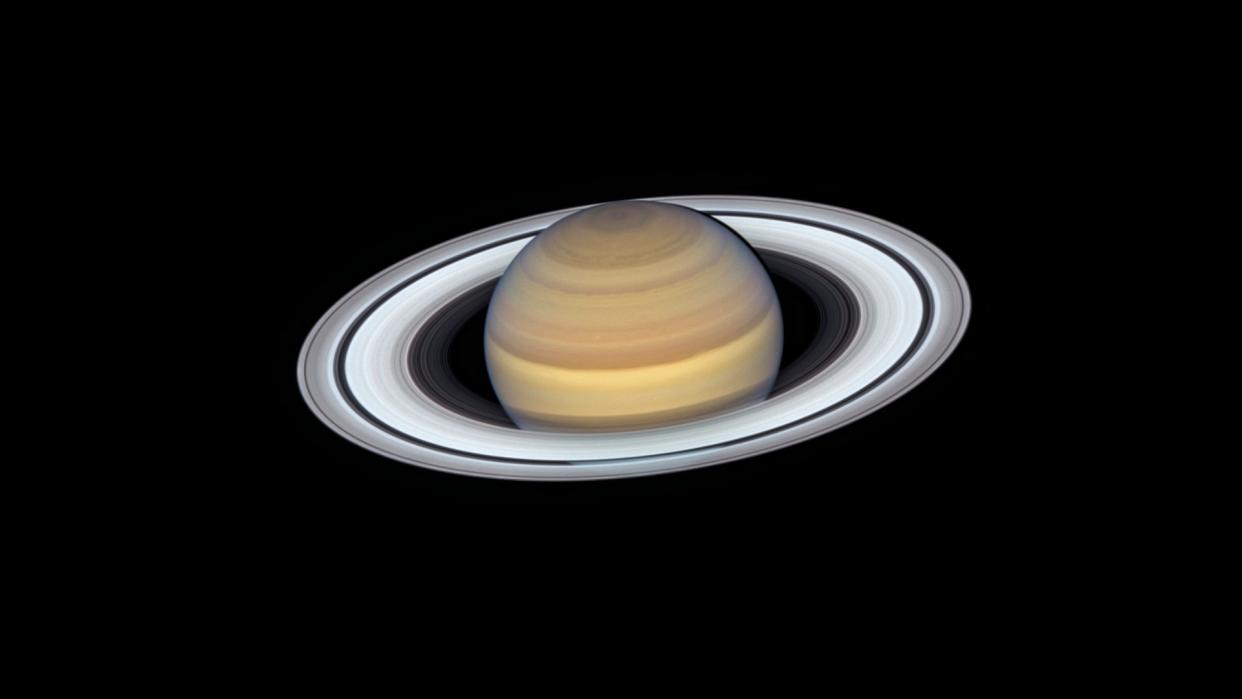

Saturn's rings are much younger than we thought

Saturn's rings are surprisingly youthful and much younger than the gas giant planet itself, new research has revealed.

A team of researchers arrived at the new birth date estimate for Saturn's rings by studying the build-up of dust around the gas giant planet. Tiny grains of rock stream through the solar system on a near-constant basis, resulting in thin layers of the material building up on planets, moons and asteroids and in icy ring systems like that of Saturn. To try and arrive at a new age estimate for Saturn's ring system, researchers studied how rapidly this dust layer gathers, similar to determining how long a surface in your house has been left untouched by running a finger over it.

The findings set a new age for the solar system's most impressive and famous ring system of no older than 400 million years. This is compared to Saturn itself, which was born with the other planets when a cloud of gas and dust around the sun collapsed around 4.5 billion years ago.

Related: Saturn's Rings: Composition, Characteristics & Creation

Conducting this investigation was no easy feat. Kempf and the team had to analyze data collected from 2004 to 2017 with the Cosmic Dust Analyzer, a bucket-shaped "scoop" instrument aboard NASA's now-retired Cassini spacecraft. Over this 13-year period, before it crashed through Saturn's atmosphere, Cassini gathered 163 specks of dust from the vicinity of Saturn.

"Think about the rings like the carpet in your house," University of Boulder physicist Sascha Kempf said in a statement. "If you have a clean carpet laid out, you just have to wait. Dust will settle on your carpet. The same is true for the rings."

Using measurements of the dust build-up on the rings of Saturn, the researchers estimated that the structures had been accumulating less than a gram per square foot of this material each year.

This revealed to them that compared to the planet, Saturn's rings are a relatively new phenomenon and could indeed disappear in a period that is equivalent to a blink of an eye — in cosmic terms, at least. The rings are being pulled back into the planet due to the gas giant's gravity, and astronomers aren't exactly sure how much longer they have.

Saturn's rings are a 'new' feature

The rings of Saturn have fascinated scientists since their discovery in 1610 by astronomer Galileo Galilei. This interest intensified in the 1800s with the revelation that the rings are not actually solid, but are composed of smaller individual particles.

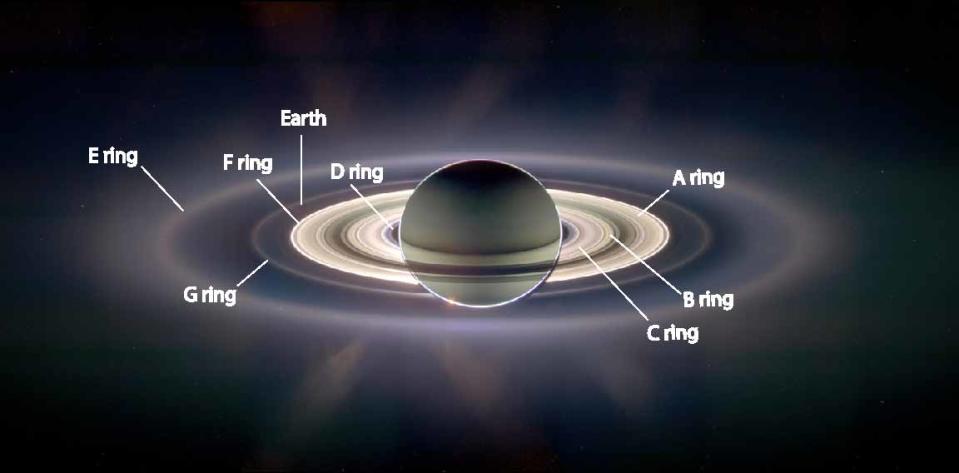

Scientists now know that there are seven rings circling Saturn extending out to around 175,000 miles (282,000) from the surface of the gas giant. The rings are made up of chunks of ice of varying sizes, with most no larger than a boulder on Earth.

What has been less clear is when the rings were born. One of the prevailing theories in the 20th century was that they were formed when Saturn itself was born. This idea is problematic, Kempf added, because the rings of Saturn are "clean" of any rocky matter, being composed of 98% water ice. "It's almost impossible to end up with something so clean," Kempf said.

RELATED STORIES:

— Saturn reclaims 'moon king' title with 62 newfound satellites, bringing total to 145

— Strange winds blow on Saturn's moon Titan. New clues could solve this decades-old mystery

The revelation of the age of Saturn's rings doesn't completely explain their origins, however, with many questions remaining to be answered.

"We know approximately how old the rings are, but it doesn't solve any of our other problems. We still don't know how these rings formed in the first place," Kempf added. "If the rings are short-lived and dynamical, why are we seeing them now? It's too much luck."

The team's work is described in a paper published in the journal Science Advances.