Savannah Morning News columnist bids an emotional farewell to his father

My father is dead.

That is the long and the short of it. It’s right there in black and white, stark, cold and sterile, a statement of unassailable fact. And yet it does not begin to capture the incredible, complex essence of my father, Harvey Jack Murphy.

His life began simply enough. On March 27, 1937, a midwife my father knew of only as “Old Mag” delivered Harvey Jack Murphy into the world inside the family’s simple cabin nestled deep on family land in rural Jackson County, Georgia.

Inexplicably, “Old Mag” incorrectly listed Daddy’s name as “Bennie Murphy” on his birth certificate, a simple error that would cause clerical confusion and administrative consternation for the rest of Jack’s life.

My grandparents, Groze and Fannie Lou Murphy, were simple folks. Daddy Groze was 25 when my father was born; Granny Fanny was only 21. It was the time of the Great Depression and work was scarce. When my Uncle Jon was born in 1940, it became even harder to make ends meet. In 1943, when my father was 6, the family pulled up stakes and moved to rural Bibb County, near Macon, to try to find a new start in life. Uncle Chip and Aunt Jo were born there, and Bibb County is where Daddy would grow up.

They didn’t have much. Things got even worse after their house burned down. They lost everything, and for a time had to live in a one-room shack in a pecan orchard. That place had a dirt floor, no running water and no electricity. Despite those incredibly humble beginnings, Jack Murphy somehow decided that he wanted to become of doctor when he was 7 years old. By the age of 16, he knew he wanted to be a surgeon.

The rest is history.

Driven and with a sharp wit

This is not an obituary, and I’m not going to bore everyone reading this with a dry recitation of my father’s accolades. There are a lot of them, but they are window dressing and tinsel, the trappings and epiphenomena of the incredible man my father was. It is that man that I hope to define here.

Daddy was smart. He had an exhaustive memory and maintained the sort of razor-sharp intellect that could cut right through any amount of superfluous fluff to get right to the heart of the matter. Once, at a Candler Central Credentials Committee meeting, my father, who was the committee chairman, listened to a fellow physician deliver a protracted diatribe against a potential young competitor who sought to establish privileges at the hospital. Daddy, frustrated with this obvious self-serving attack, cut the man off, saying, “Listen, I just had cataract surgery, and my vision is excellent. And I can see right through you.”

The physician, chastened, promptly sat down and shut up.

Daddy was tough. He expected a lot out of us. That could be hard to deal with sometimes. When I was in high school, he once challenged me by saying I would “never get any scholarship money.” I took that as a personal affront. Wanting desperately to prove him wrong, I made it my crusade to get as much scholarship funding as possible. Later, when I proudly informed him about one particularly large scholarship award, he nodded, smiled, and said, “I knew you’d do that. Why do you think I said to you what I did?”

Daddy was driven. His incredible drive to succeed came from someplace deep inside him, a wellspring of self-determination that refused to accept anything other than the exceptional. He always believed in himself. He used to tell this story about when he was a medical resident: After church on Sunday, Mama and Daddy used to eat lunch at the hospital cafeteria, where the food was free. One of those days, Mama was staring down at the sidewalk as they walked into the hospital.

“What are you looking at?” Daddy asked.

“I’m just trying to see if I can find some money on the ground so we can go eat at a real restaurant sometime,” she replied.

Daddy put his arm around her and said, “Honey, if you just stick with me, I promise you we’ll go to plenty of real restaurants. Nice ones, too.”

And they did, of course. He was as good as his word.

Daddy’s intellect, toughness and drive got him through some very hard times. The resilience he derived from those innate qualities allowed him to overcome obstacles that would have defeated most folks.

Jack Murphy simply refused to be defeated. He would not allow it.

'He truly cared about his patients'

What made Daddy truly unique was that he was able to marry that drive and perseverance to a sense of compassion and fair play. There are plenty of driven, successful people in the world, but many of those sorts of people are sociopaths, individuals willing to trample others on their climb to success.

Daddy was not like that.

He was compassionate. He truly cared for his patients, always going the extra mile for them without any expectation of reward or accolade. He made house calls when that sort of thing was called for. He took care of the less fortunate members of our community and simply wrote the bills off as a function of his calling as a physician. Daddy provided free medical care for the boys at Bethesda, for example, and routinely visited the nuns cloistered at the Carmelite Monastery on Savannah’s southside. As a child of the Depression, he was very careful with his own money, but he was not a grasping, miserly sort or person when it came to his patients. He always tried to do what was right and fair, and he instilled that belief system in all his children.

My father absolutely loved being a surgeon. He sometimes hung out in the ER, simply looking for people to operate on. He told us stories about those experiences that still reverberate today. One of his favorite tales involved a couple of “good old boys” who were out fishing one day when they came upon a chimpanzee troop, which the Yerkes Primate Institute had stationed on uninhabited Bear Island, near Ossabaw. Coming ashore, the fishermen threw the chimps a can of beer and found that the chimps could open the beer can’s pop top. Moreover, they found that the chimps really liked beer. All was well and good until the beer ran out. After that, the entire troop of enraged, drunken apes chased the two fishermen around the island for an hour or so until they finally escaped in their boat, prompting one of the men to comment, “Thank God those damned things can’t swim!”

Daddy’s love for surgery was contagious, and he instilled that love of his profession in a number of medical students and residents, many of whom still practice in our community today. Years ago, he hired a recent high school graduate as one of his office receptionists. Realizing how bright she was, he encouraged her to go back to school, and inspired her to become a doctor herself. That person, Dr. Paula DeNitto, became a successful surgeon in her own right, saving many lives in our community. Paula was like a second daughter to my father, and he loved her to the very end.

Murphy Column: The future is now for healthcare advances

More Murphy: Celebrating the boys and bruises of fall

A country boy from rural Georgia at his core

When he was outside of the hospital, Daddy was still at his core a country boy from rural Georgia. A Southerner through and through, he loved dogs, hunting, fishing, NASCAR, and college football, particularly the Georgia Bulldogs. A Georgia season ticket holder, he and Mama loved going to games in Athens, and we even went as a family to the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans a couple of times. Just a few weeks ago, Daddy and I were watching the much-ballyhooed Ohio State-Michigan game on TV, and he said in disgust, “Just turn that crap off. I don’t want to waste any more time watching that boring-ass Yankee football. I’ll just wait until the Georgia game comes on.”

My father’s faith was important to him. He accepted Christ as a young man and served as a deacon in his church. He also used Christ’s teachings as a template for his behavior, reading extensively about modern-day Christian martyrs like Dietrich Bonhoffer, who the Nazis hung for resisting the Third Reich.

Daddy wasn’t all perfect. For a surgeon, he had an incredible lack of mechanical aptitude. On Christmas morning, when I was 11 years old, Daddy came into my bedroom and woke me up.

“Mark, get up. I need you downstairs,” he said.

I was horrified.

“Daddy, I can’t. It’s Christmas Eve. If Santa comes and sees me, he’ll go back up the chimney and leave us no presents.”

Daddy shook his head and said, “I’m Santa, dammit. Now get dressed and come downstairs with me, right now.”

The living room floor, where our Christmas tree was located, looked like a war zone. It was littered with bike parts, telescope tubes, half-assembled electrical devices, pieces of a model train set, and Easy Bake Oven debris.

“Oh, wow,” I said under my breath.

Daddy and I sat down and assembled all the gifts “Santa” had brought, finishing just before dawn. He then ordered me to go back to bed.

“Remember to act surprised when you come downstairs,” Daddy said.

I did not sleep long. Andy and Jennifer awoke at daybreak—and they were excited.

“Mark, get up! Santa came!” they said, excitedly.

“I know,” I said with a groan, rolling over and covering my head with my pillow.

“What’s wrong with you?” Jennifer asked. “Are you sick?”

Her love made Daddy a better man

Daddy could talk a blue streak. I suppose that’s a Murphy family trait. When Jennifer was married at First Baptist Church nearly 30 years ago, Daddy and Jennifer talked the whole way down the aisle, prompting Sister Mary Faith Graziana to remark, “Leave it to a couple of Murphys to keep talking with each other going down the aisle until the very last minute.”

My father had a great sense of humor. He once sent a tree frog through a pneumatic tube in St. Joseph’s Hospital, then ran up to the nurse’s station to watch the nurse's reaction when she opened it. The frog jumped out. She screamed and dropped the tube. Daddy, laughing, scooped up the wayward amphibian and released it back into the wild. A nurse at St. Joseph’s reminded us of that story while Daddy was hospitalized there just last week.

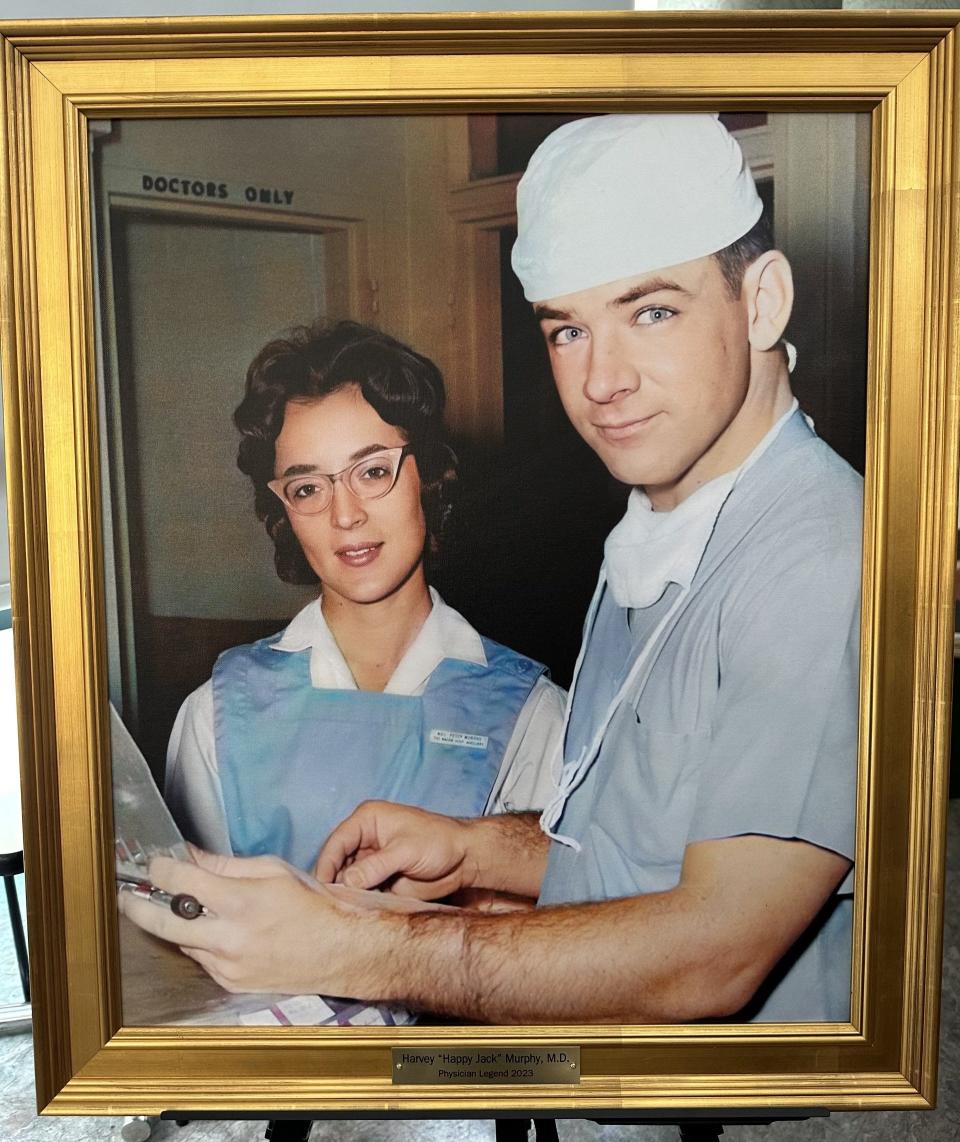

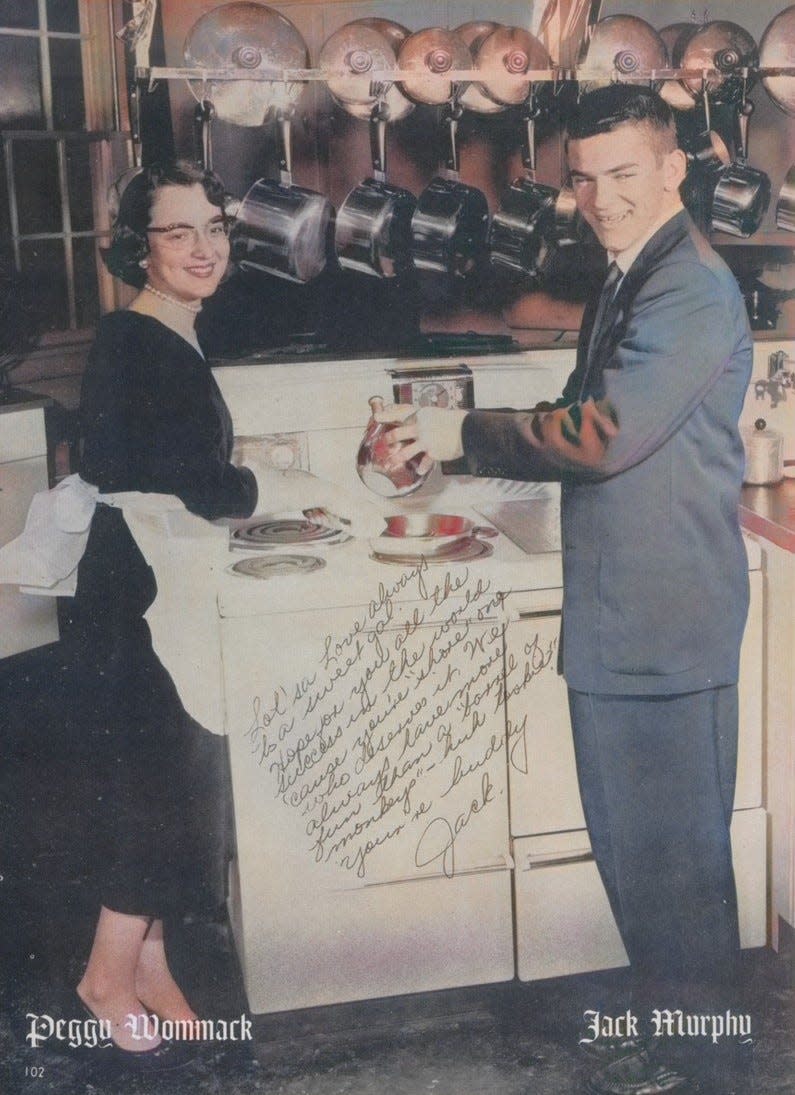

At work, Daddy was known for always being upbeat and energetic. He whistled so distinctly whenever he strode through the hallways of Candler, St. Joseph’s, and Memorial Hospitals that everyone could always tell when he was coming. Daddy was so consistently gregarious and entertaining that the nurses nicknamed him “Happy Jack.” Several nurses told me that after my mother died, he was never quite the same, however—and it’s true. We all saw it.

Daddy’s marriage to Mama cemented the most important relationship in his life. Mama was Daddy’s soulmate and his inspiration. Her selfless, unconditional love completed him, driving Daddy to be a better man and making him whole. Their love for one another was transformational, galvanizing Jack Murphy into the person he ultimately became.

From Mama and Daddy’s love for one another comes the sort of personal vignette that Jennifer, Andy, and I will always remember: Daddy, still in his surgical scrubs, hunched over the oak kitchen table at 201 Lee Blvd., exhausted and smelling of soap and Old Spice as he snarfed down a re-heated plate of fried chicken and greens. Mama, coming up behind him, wrapping her arms around his neck and kissing the top of his balding head.

From my mother, I learned compassion and love of family. From my father, I learned how to be a better father, husband and doctor. From both, I came to understand the honor, duty and self-sacrifice inherent in each. Our parents gave everything they had to each one of us, and that is a debt that can never be repaid.

Life is precious, messy, and raggedly impermanent. There are no guarantees. Mama’s brilliant life was snuffed out suddenly and tragically at age 50. Her devastating loss made all of us understand how incredibly precious life is and how important it is to love the people you love with all your heart, every single day.

One final thought here: My father, a barefooted farm boy, decided to become a doctor at a young age. Years later, following the path he had previously blazed, I followed him into medicine.

When my wife Daphne was first diagnosed with cancer at age 28, my medical training allowed me to seek out the very best medical care I could find for her.

She survived.

I’ve never been a believer in predestination, but I certainly believe in God. And I know that Daddy’s decision to become a doctor all those years ago had a role in saving Daphne’s life.

Daddy carried a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson in his wallet which exemplified what has driven him throughout his entire professional career: “If a man loves the labour of his trade, apart from any question of success or fame, the gods have called him.”

Daddy’s gone now, but not really. He has been reunited with Mama, at long last. Moreover, he lives on inside of each one of us, in all five of his grandchildren and in his great-granddaughter, as well. Happy Jack Murphy’s values are our values, even as his DNA is in our DNA. He helped make each one of us.

What is truly incredible is how his vision for how his own life should turn out positively altered the trajectory of every other family member. With no real role model and no blueprint for success, Jack Murphy decided what and who he wanted to become and made it happen through perseverance and hard work. He dedicated his whole life to the service of others. He was smart, tough, iron-willed, frustratingly stubborn at times, but also funny, engaging, compassionate, and painfully honest. Every single person in our family has their set of Jack Murphy stories. In that respect, not only is his soul immortal, but his memory is, too.

So to “Happy Jack” Murphy, my father and my role model: Thank you, from all of us. You lived an incredible, fantastic life. Most importantly, you were a wonderful husband and soulmate for Mama and a great father to me, Jennifer, Andy—and to Paula Denitto, your professional “daughter,” too.

We love you, and we will all miss you.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Mark Murphy bids father Happy Jack Murphy farewell in column