Saving America's salt lakes, great and small

Utah's Great Salt Lake is in imminent danger of drying up to the point of ecological collapse, putting Salt Lake City and the majority of Utah's population in serious danger of being plagued by a toxic cloud of carcinogenic dust laced with arsenic and other heavy metals. And the Great Salt Lake isn't the only endangered saline lake in the Great Basin of the U.S. West.

Things are so dire in the Great Basin that leaders and policy makers in Utah and Washington, D.C., are paying attention. Here's how they are trying to save America's salt lakes, great and small.

What's happening to the Great Salt Lake?

The Great Salt Lake, the largest remaining saline lake in the Western Hemisphere, is disappearing. The lake has shrunk by two-thirds since the late 1980s and hit its lowest level in recorded history in fall 2022.

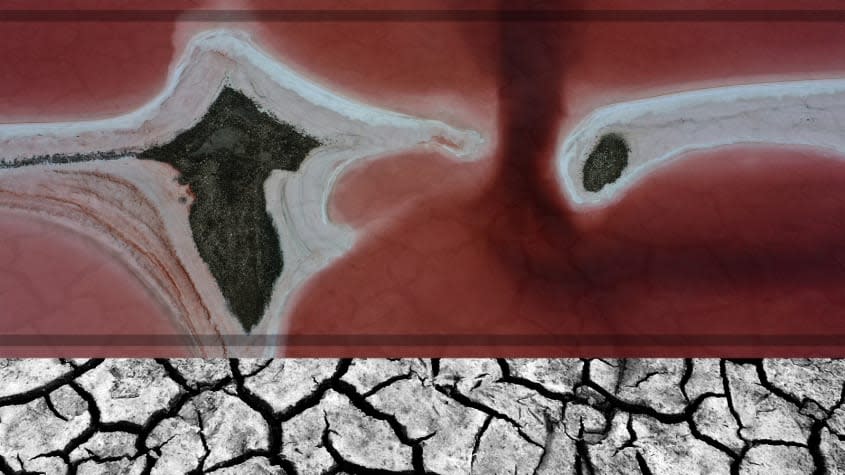

The receding water exposed 800 square miles of lake bed salted with natural and manmade toxins, including mercury, arsenic, and selenium.

The Great Salt Lake, like the other saline lakes, is a "terminal lake" — so called because the rain, snow runoff, and other water that feeds the lakes have no exit point. It loses some 2 million acre-feet of water through evaporation each year, and in 2022 only about 1.2 million acre-feet flowed into the lake. Rapid population growth in Salt Lake City and the surrounding Wasatch Front valley has combined with the changing climate, lengthy drought in the U.S. West, and diversion of the feeder rivers to farms to keep the lake from being replenished.

The situation improved over the winter with an above-average snowpack in the surrounding mountains that, when it melts, could raise the lake level by maybe 3 feet. The docks are already floating again, though barely, in the Great Salt Lake State Park marina. But that's just a band-aid. A recent study from Brigham Young University warned that without action, the Great Salt Lake could "evaporate into a system of lifeless finger lakes within five years, on its way to becoming the Great Toxic Dustbowl," CNN reports.

What about the other saline lakes?

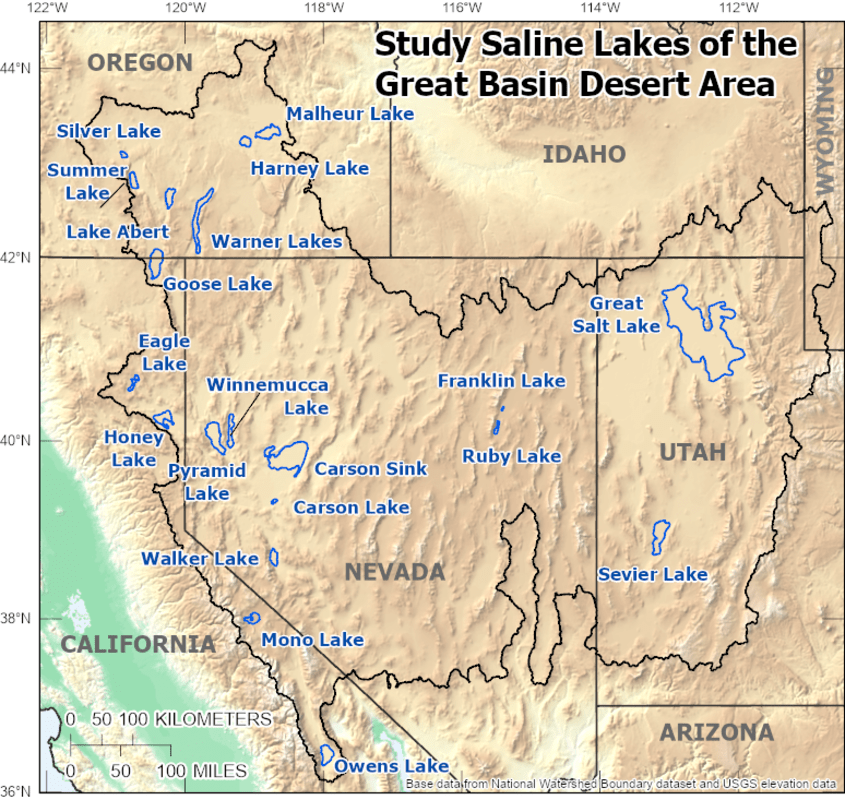

The U.S. Geological Survey and its partners have identified 20 saline lakes, including the Great Salt Lake, as ecosystems in need of saving in four states of the Great Basin — California, Nevada, Oregon, and California.

U.S. Geological Survey

The Great Basin is an area covering more than 190,000 square miles of arid valleys and ridges between the Sierra Nevada and Cascades mountain ranges on the west and Wasatch Mountains on the east, with the Columbia Plateau marking the northern edge and the Mojave Desert on the less-defined southern border. The defining hydrologic feature of the Great Basin is that the water all drains inward, not into the ocean or a river that leads to the ocean.

The Great Basin's saline lakes "tend to be what are called terminal discharge points where water, either surface or groundwater, is the end of the flow path," David O'Leary, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey Utah Water Science Center in Salt Lake City, tells Deseret News. "Typically the only way for water to leave is through evaporation, and that leads to the saline buildup."

"There is a concern for the long-term viability of these lakes," O'Leary added.

Why bother saving lakes unfit for drinking or fishing?

The saline lakes may not be potable or teeming with bass, but they aren't lifeless either. The brine shrimp and flies that live in the Great Salt Lake are an important food source for the 10,000 migratory birds that flock to its placid waters. And people depend on the lakes, too, for recreation and mining, among other things.

"These lakes are relics of the past, and they hold a lot of answers to the way Mother Earth changes," Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network, tells Deseret News, "and I think we need to use them as a barometer about the future — where we have been and where we are now."

Further depletion of the saline lakes "threatens the canals and infrastructure that a multi-million dollar mining industry needs to extract salts from the lakes," The Salt Lake Tribune reports. In Utah, "ski resorts worry about a future without lake effect snow." And when the lakes dry up, they leave behind dust that can be blown into the air, endangering the health of nearby communities. That's a huge issue for Salt Lake City and Utah's other population centers, but not just those cities and towns.

As a cautionary tale, proponents of saving the saline lakes "point to California's Owens Lake, which was notoriously drained by developers in the 1920s to build Los Angeles and inspired the watery, 1974 noir Chinatown," CNN reports. "By 1926, the terminal lake was dry and producing billowing clouds of fine, toxic dust which became known as 'Keeler fog' after it forced people in the town of Keeler to relocate." Los Angeles is still paying to clean up that mistake — $2.5 billion and rising.

"It was human choices that led to that catastrophic event," Brian Steed, executive director of Utah State University's Janet Quinney Lawson Institute for Land, Water, and Air, tells CNN. "We're looking at the Great Salt Lake in a position right now to where we can avoid that catastrophe, where we don't have to spend those billions of dollars in remediation in the future if we make choices today."

What are people doing to save the lakes?

Utah and the federal government are pouring money into researching the issue to come up with long-term solutions, and Utah is also taking short-term steps to stave off disaster.

President Biden in late December signed the bipartisan Saline Lake Ecosystems in the Great Basin States Program Act, which allocates $25 million over five years to USGS to establish a program to "assess, monitor, and benefit the hydrology of saline lakes in the Great Basin," plus the migratory birds and wildlife that depend on those ecosystems. Efforts to save the Great Salt Lake and other Great Basin lakes also got $40 million from Utah's Legislature last year and $10 million from the federal government through a defense spending earmark for the Army Corps of Engineers.

Utah lawmakers are also considering a range of mitigation measures, from restricting lawn irrigation to conserve water in some cities to less plausible ideas like cloud-seeding, thinning forests in the mountains around the Great Salt Lake, and building pipelines to suction up water from the Pacific Ocean. "We are getting some really fantastical suggestions from some of our lawmakers as to how to solve this," says Dr. Brian Moench, president of Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment, who advocates buying out water-intensive alfalfa farms to divert less water from feeding the lake.

About 63 percent of the water diverted from the Great Salt Lake goes to farmers, so they are an obvious part of the solution. "I think that the cheapest solution is for the state to buy some of the farmers out of their water rights and release some of this water in the natural system," Bonnie Baxter, director of the Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College, told CNN. "I know the farmers that I've talked to, they want to be part of the solution. They live here too."

Other ideas include limiting mining in the lake if the level gets too low, paying for farmers to install more water-conserving irrigation, and freezing any new developments that use more water than they save. Gov. Spence Cox (R) split the Great Salt Lake in two with a Feb. 3 executive order that instructed the Utah Division of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands to raise the berm in the Great Salt Lake railroad causeway by 5 feet, in an effort to raise the water level in the southern, less salty arm of the lake, protecting it from the super salty northern end. The berm was raised 4 feet last year for the same purpose.

Raising a dam to save half the lake works as a temporary fix, but too may "pie-in-the-sky" ideas and the federal government will have to step in, BYU ecosystem ecology assistant professor Ben Abbott told ABC 4. "The safest and most cost-efficient route is to conserve water," he added. "That's the only option that doesn't have a big trade off."

You may also like

Trump's plan for a 2nd term reportedly includes firing squads, hangings, and group executions

Student loan borrowers are pinning their financial futures on debt forgiveness

United Airlines flight plunged to within 800 feet of Pacific Ocean