How 'the Savior of Cincinnati' kept the city from having its darkest day

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What could have been Cincinnati’s darkest day did not turn out that way.

During the Civil War, Cincinnati had a bit of a buffer from the South because Kentucky, a slave-holding border state, did not secede from the Union. But in the late summer of 1862, Confederate forces were finding it easy to waltz in and capture Lexington and Frankfort. Cincinnatians feared they were next – and they were.

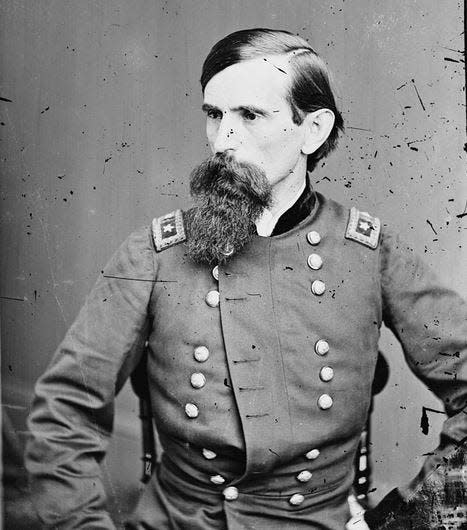

That Cincinnati did not fall was largely due to the leadership of Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace, a Union general who was dogged by controversy after the Battle of Shiloh a few months earlier. His defense of Cincinnati maybe only happened because he was trying to prove himself after Shiloh.

Our History: What was it like to live in Cincinnati in the 1870s? Let's travel back in time

Lew Wallace hailed as 'The Man Who Saved Cincinnati'

We don’t hear much about Wallace in Cincinnati. Author Peter Bronson, a former Enquirer editorial page editor and columnist, may help change that with his new book, “The Man Who Saved Cincinnati.”

Bronson, a Civil War hobbyist, learned about Wallace’s story at the historic Shiloh battlefield.

“When I discovered the Cincinnati connection, that was it. It just told me, here is a great story,” Bronson said. “This is one of those treasures of history that people have lost and needed to be brought back to light.”

As he did with “Forbidden Fruit,” his book on Newport’s mob corruption days, Bronson writes much like a historical movie based on a true story with a few characters added to help the reader get into the moment, such as Bronson’s great-great-grandfather, who fought with the 12th Michigan nearby at Corinth and possibly at Shiloh.

The book covers more than Wallace’s Civil War service. Wallace later spent four years as governor of the New Mexico Territory during its lawless, Wild West period and captured Billy the Kid. He also wrote “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ,” the most popular novel of the 19th century.

“He was such an amazing man to accomplish all these things in one lifetime,” Bronson said.

Wallace unfairly blamed for losses at Shiloh

Wallace’s experience at Shiloh is key to understanding him. The youngest Union general at age 34, he taught himself by reading books on military campaigns.

“He always had a little bit of a chip on his shoulder about that because people didn’t respect him unless he had his credentials that they had at West Point,” Bronson said.

On April 6, 1862, Confederate troops stormed Federal camps near Shiloh Meeting House, a church in southwestern Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered Wallace to bring his division to the defense of the army troops. His verbal command was written down by an aide but the paper was lost to history. Wallace swore Grant didn’t specify which road to take – the improved Shunpike Road or the flooded River Road. He took Shunpike, but Grant wanted him to take River Road.

Due to the confusion, Wallace didn’t arrive at the battlefield for the first day of fighting. The Union won the battle on April 7, but the failures and casualties from the first day were pinned on Wallace rather than on Grant.

“History has judged Lew Wallace very unfairly,” Bronson said. “As I dug into it deeper and deeper, I saw that this was really a coverup of Grant’s mistakes and they needed somebody to scapegoat. … Wallace spends the rest of his life trying to redeem himself from this unfair slander that was orchestrated by Grant’s senior staff members.”

Defending Cincinnati from Confederate siege

A few months later, Wallace was in Cincinnati when the Queen City needed him most.

Confederate Maj. Gen. E. Kirby Smith captured Richmond, Kentucky, on Aug. 30, 1862. Three days later, 11,000 Confederate troops entered Lexington to cheers from the populace. Then Frankfort fell. Kirby soon dispatched Gen. Henry Heth with 9,000 men to capture Cincinnati.

Meanwhile, panicked Cincinnatians prepared for a siege. Wallace took command of Cincinnati, Newport and Covington and declared martial law on Sept. 1.

The next day The Enquirer printed his declaration: “It is but fair to inform the citizens that an active, daring and powerful enemy threaten them with every consequence of war; yet the cities must be defended and their inhabitants must assist in the preparation. Patriotism, duty, honor and self-preservation call them to the labor, and it must be performed equally by all classes.”

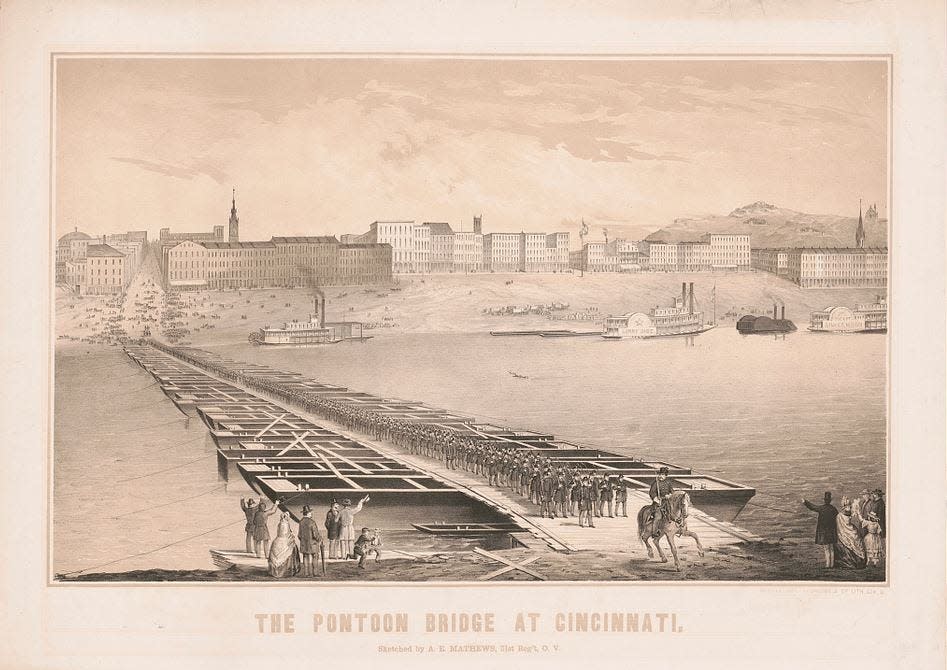

With no army to defend Cincinnati, the citizens would have to step up. No bridge crossed the Ohio River yet, so barges were strapped together for a makeshift pontoon bridge to reach Kentucky. He called out for armed volunteers from across Ohio.

Black Brigade given the dignity of volunteering after racist abuse

Under the orders of Cincinnati Mayor George Hatch, the city’s Black men were apprehended to do the labor of digging rifle pits, building fortifications and clearing roads in Northern Kentucky.

“Cincinnati’s freed black men were abused, routed up at the point of a bayonet, forced into a mule pen, then dragged across the river into a slave-holding state where their freedom was now completely in jeopardy and forced to dig ditches and rifle pits and build roads for the defense of Cincinnati, until Lew Wallace heard what Hatch was doing,” Bronson said.

Wallace ordered the organization of the Black Brigade, with abolitionist Col. William M. Dickson in command. The 300 kidnapped Black men were sent home and given the dignity of volunteering. The next day, 700 volunteers for the Black Brigade showed up.

“This was the first time Blacks were given a chance to fight for their own freedom, to contribute to the battle,” Bronson said.

'Perfect person to save the city'

A force of some 70,000 soldiers – a mix of the regular army and volunteers – showed up to defend Cincinnati. That number included 15,000 backwoods fighters known as “Squirrel Hunters,” armed with pistols, shotguns and sporting rifles.

When the Confederate troops arrived, they found Cincinnati was prepared to defend itself. Realizing that invasion would not be easy, Heth and the Confederates pulled out during the night of Sept. 11.

Wallace addressed the people of Cincinnati: “In coming time, strangers viewing the works on the hills of Newport and Covington will ask, ‘Who built these intrenchments?’ You can answer, ‘We built them.’ If they ask, ‘Who guarded them?’ you can reply, ‘We helped in thousands.’ If they inquire the result, your answer will be, ‘The enemy came and looked at them, and stole away in the night.’”

The people called Wallace “the Savior of Cincinnati.”

“He united the town in such a way that was inspiring,” Bronson said. “Doctors and ditch diggers side by side. Lawyers and laborers. All these people that were pulling together, and for just those weeks they put aside all their hostility and divisions over class and religion and race and everything else. All of these things disappeared for a while.”

Wallace was the right man in the right place at the right time for Cincinnati, in its time of greatest need. Even if it was because of an injustice done to him.

“In many ways I don’t think he would have done what he did in Cincinnati if he hadn’t been through that at Shiloh,” Bronson added. “He was so eager to show that he could do what had to be done in a tough situation. … That guy, it turned out for Cincinnati, was the perfect person to come here and save the city.”

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: How this man saved Cincinnati from Confederate forces during Civil War