SC community used sludge fertilizer, then residents got sick. Are they connected?

On a placid day three decades ago, men from a local textile factory spent hours at the O’Neal family’s farm, pitching a plan they said could save money on the cost of fertilizing crops.

The idea was to spread the textile plant’s waste on property the O’Neals had been farming for generations. The waste sludge contained nutrients that would make crops flourish — and, unlike commercial fertilizer, it wouldn’t cost the family a dime.

So the O’Neals, like other farmers in their community, agreed to use the sludge.

But in 2019 the government began to find hazardous chemicals in the drinking water of local farmers and their neighbors.

All of them lived and worked in areas where farmers had used sludge from the Galey and Lord textile plant. And many of the wells they drank from were polluted with the same chemicals being found in sludge at the factory several miles away.

As the community learned about the water pollution, some residents began to question why they or their loved ones had become sick and whether the contamination would affect the future use of their land in rural Darlington County.

Many of them today are angry and asking why the textile plant — with the blessing of state government officials — assured them the Galey and Lord sludge was safe.

“It has leached into our drinking water and poisoned us,’’ said Robert “Robbie” O’Neal, III, a stocky 57-year-old with a clipped gray mustache who has spent most of his adult life farming the land his father, uncles, cousins and grandfather toiled for decades.

The threat the O’Neals face is perhaps the most stark example of how a program allowing sewer sludge to be used as fertilizer could be imperiling drinking water, crops and property values for people across South Carolina. It could be affecting residents’ health too, some say.

Since the early 1990s, municipal wastewater plants and industries have spread sludge on thousands of acres of agricultural land in South Carolina as a way to get rid of the gooey refuse, often in the name of good farming practices, according to records examined by The State and its parent company, McClatchy.

All told, more than 3,500 farm fields have been approved to receive sludge. Sewage plants, factories and other types of industrial facilities were approved to spread sludge and wastewater by the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control. Clusters of sites are found from the hills near Greenville to the flat landscape of the Pee Dee.

Now, increasing evidence shows that some sludge contains chemicals with a toxic punch called per and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. The class of toxic compounds has only in recent years become widely known to the public.

Commonly called forever chemicals, the material is of such concern that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has proposed a strict drinking water limit of 4 parts per trillion on some types of the chemicals. Forever chemicals got their name because they do not break down easily in the environment, meaning they can pollute the earth, rivers and groundwater for decades.

Few, if any studies, are known to have been conducted to assess the threat of the sludge application program on people in South Carolina. But other states, such as Maine, have linked sludge fields to well pollution and contaminated crops.

Forage grass, which is eaten by cows, has a high potential to take in PFAS from contaminated soil, which in turn creates a risk that PFAS will show up in cows’ milk, according to the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Service.

In one well-publicized case, a Maine farmer whose land was used as a sludge field was forced to shut down his dairy operation after PFAS was found in the milk.

It’s not known whether crops or grazing livestock in South Carolina are being polluted by PFAS from sludge. But the chemicals are showing up in almost every river tested in the Palmetto State, often at levels above the proposed federal drinking water standard. Similar trends are being found in public drinking water plants that draw from rivers and groundwater near sludge fields.

Some people who drink from private wells also are affected, including farmers who say they innocently accepted industrial sludge without knowing the potential long-term impacts of participating in waste spreading programs.

Forever chemical pollution could come from an array of sources. Direct discharges of wastewater to rivers, leaks from military bases and mine pollution are among them. Some types of fertilizers could have contributed to PFAS found on farmland, several environmental groups have reported recently.

But land application of wastewater sludge is one of the main suspected sources of PFAS pollution in rivers across the state, according to a 2021 publication by DHEC. Environmental groups that say pesticides are a possible source, also say sludge is a major potential reason for PFAS pollution.

“It’s sad. We didn’t know what we were doing to the ground,’’ O’Neal said of the sludge spreading program his family once relied on. “We were told it was supposed to be good, supposed to be nothing wrong with it. It wasn’t supposed to hurt anything.’’

While enriching crops with nutrients, the sludge was “bad on everything else,’’ he continued. “If I’d have known then what I know now, I would never have used it.’’

Toxic triangle

The sludge that workers spread on the O’Neal’s agricultural fields came from a hulking textile plant in Society Hill that once employed hundreds of people but today is an abandoned site targeted for a taxpayer-funded cleanup.

The area, beloved by the multi-generational families who call it home, is a flat, picturesque landscape of farms and blackwater streams. Forests burst with color each fall and spring.

It is composed almost entirely of crop fields, pastures and modest homes, with a railroad office, a smattering of businesses and a small local air strip mixed in.

The ties between the people and the land run deep here, said Randell Ewing, a local tree farmer who has been active in conservation.

“These people have owned ... some of this land for generations and generations,’’ he said, adding that no one he knows would have accepted sludge from the Galey and Lord plant if they thought it was anything other than a benign fertilizer. “I can assure you they would never have done anything knowingly, that they were going to hurt their land. People love their land. “

“I know I would have never allowed it if I knew what was coming up now.’’

Ewing, 77, signed a document approving sludge to be spread on his land.

“I doubt very seriously we read what we were even signing because we were just told’’ it was safe, he said.

Efforts by the newspaper to reach Galey and Lord representatives were unsuccessful. But the high cost of sending sludge to a landfill may have been the reason the company sought farmers’ permission to deposit the material on their land.

Sludge spreading rose nationally in the 1980s, in part because of the increasing cost of shipping the material to landfills, according to a 2000 biosolids fact sheet by the EPA. Using sludge has been advocated by state and federal officials in the past as a way to reuse waste material that would otherwise wind up in a landfill.

Robert “Bobby” O’Neal Jr, Robbie O’Neal’s father, said Galey and Lord’s offer of free sludge in the early 1990s didn’t actually save him much money. The elder O’Neal, 79, said he still had to buy fertilizer to supplement the sludge used on his fields, despite the company’s assertions.

“It didn’t improve the situation that much, no,’’ Robert O’Neal Jr. said.

Sickness and despair

The United States and other countries have used different types of PFAS for the past 80 years as an ingredient in many consumer products. It repels water from windbreakers, protects carpet from stains, makes for non-stick frying pans and is a key ingredient in foam used to extinguish fires.

But while popular in consumer products because of its durability, that characteristic also means many types of PFAS don’t break down in the environment quickly, thus the term forever chemicals. Thousands of forever chemicals exist, with the two most common being PFOA and PFOS.

Exposure to PFAS over time has been tied to kidney, testicular and breast cancer, ulcerative colitis and thyroid problems. It also can weaken a person’s immune system and cause developmental delays in children, according to a 2022 report for doctors by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

Nationally, forever chemical manufacturers for decades kept the threat of PFAS to themselves, despite learning of its dangers more than 60 years ago.

Multiple in-house studies about health threats were not publicized, and only when a West Virginia farmer’s cows began to die in the late 1990s, did forever chemicals gain wider attention nationally.

The discovery led to a 1999 lawsuit against Dupont, a major PFAS manufacturer, and eventual action by the EPA, according to The New York Times magazine. In 2006, the federal agency reached a $16.5 million settlement with Dupont. The EPA accused Dupont of keeping the hazard secret.

It took time, however, for information about the forever-chemical threat to become fully realized in many states.

Rob Devlin, an assistant DHEC water bureau chief and a 35-year agency veteran, said he had never heard of PFAS until a few years back “after the Dupont’’ report came out.

In the past four years, South Carolina regulators have begun to play catch up on the issue, testing wells in Darlington County following the shutdown of Galey and Lord in 2016, as well as looking at other potential problem areas statewide.

“Our goal at DHEC is to be as upfront and out in front of this issue as possible, as it relates to South Carolinians,’’ agency spokesman Ron Aiken said. “This is an issue that faces everybody.’’

Some wells are polluted enough that the EPA has installed filters in an effort to protect people. And a local utility is planning to run public water lines to the area in the next year.

Still, those efforts won’t protect the farmers and their neighbors from past exposure. Many of them drank water for decades from areas where the sludge was applied, not knowing what was in the Galey and Lord waste.

As he stood in front of a tangle of machinery, silos and farm sheds on a warm spring day, Robbie O’Neal said his family’s health problems make him wonder if the water contributed to their afflictions.

It’s not a statement he makes lightly. O’Neal is from conservative stock, a rural man who is among President Joe Biden’s critics. O’Neal isn’t the type of person to complain about environmental problems. But anybody who had been through what his family experienced would have concerns, he said.

His Uncle Mark died in 2006 at the age of 52 after contracting pneumonia, a disease that can result from a weakened immune system, one of the signs of prolonged exposure to forever chemicals.

His uncle’s well registered 160 parts per trillion for one type of toxic forever chemical. The federal government has proposed a drinking water limit of 4 parts per trillion because of the hazards of forever chemicals. Mark O’Neal drank the water for much of his adult life, Robbie O’Neal said.

Another uncle, John O’Neal, had lung cancer, likely from years of smoking. John O’Neal died in May after a brief bout with pneumonia. John O’Neal’s well registered levels 775 times higher than the proposed federal limit.

In addition, the wife of Robbie O’Neal’s cousin has had ovarian and breast cancer. Although research is still underway, limited findings show that exposure to PFAS is tied to an increased risk of breast cancer, according to the National Academies.

Doyle O’Neal, Robbie O’Neal’s cousin, is skeptical about whether his wife’s ovarian and breast cancer are tied to drinking PFAS-tainted water. But it’s also something he’s thought about.

Although he said his own well has not shown unsafe levels of PFAS, wells on land he owns nearby have. One of them was next door, at the home where his mother lived.

Doyle O’Neal, 67, said his mother died about 15 years ago after drinking well water most of her life. She had breast cancer.

Federal and county records show the well at his mother’s house had levels 55 times higher than the proposed limit.

Among the hardest things to prove in any pollution case is whether contamination has impacted people’s health. In this case, the science on health effects of PFAS is still emerging and, unlike some types of pollution, such as lead in drinking water, less is known about forever chemicals.

It’s possible that other environmental factors caused illnesses, certainly in those who smoked and developed lung cancer. But when told about Mark O’Neal’s death, East Carolina University health researcher Jamie DeWitt said pneumonia is a condition that could be tied to PFAS exposure.

“It’s hard to say whether that death arose from a suppressed immune system linked to the PFAS he was exposed to,’’ she said. “But it is more than possible.

“Somebody who died of pneumonia at that age had to have something wrong with their immune system,’’ she said.

Sweet water, hidden toxins

The O’Neals are far from the only ones with unanswered questions about their family’s health.

Not six miles away from the O’Neal’s land, lies a mobile home where Shirley Alford raised four children.

Alford, 67, remembers the good times she had after moving there some 30 years ago. One of her vivid memories is how good the well water tasted.

She used to put glasses of well water in the freezer. Just before the water froze, Alford would snatch the glasses from the icebox and serve them to her family. It was a frigid treat on the sweltering days that grip Darlington County in the summer.

“It tasted so good,’’ said Alford as she recently sat beneath a shade tree in her yard and reflected on her life on the rural dirt road.

Alford now worries that the sweet-tasting water she drank for more than 30 years was polluted with forever chemicals. The government installed a filter on her well in March after determining the water was not safe, she said.

But how long had it been like that, Alford asked? How has exposure to the water affected her family’s health and why wasn’t something done sooner, she wonders?

Alford has had much of her stomach removed because of cancer. A grandchild is experiencing seizures. So is another grandchild. Both live on the property Alford shares with her daughter-in-law. Both of the children are taking medicine for the conditions.

The family doesn’t know if the health problems are tied to the PFAS exposure since a number of factors could be the reason. But Alford said she and her family should never have been put at risk.

She’s upset about the threat over the 30 years she’s lived on Journey’s End Road, but also that the EPA didn’t install a filter on her well until this spring, even though measurable PFAS levels were found in the water two years ago.

“Somebody could have told us and we wouldn’t have been drinking the water and cooking with it,’’ Alford said. “I used to have kids over here. I cooked for them and they were drinking the water. I made Kool-Aid.’’

Records provided by Alford’s landlord show that in 2021 her well had levels of one type of forever chemical at four times what today would exceed the proposed federal standard. Since then, the levels have at least doubled, according to the EPA.

At least five other families on Alford’s road also are dealing with PFAS pollution. Forever chemical levels at some of the homes, already high during 2021 tests, have risen since then, data from the EPA show.

The exact source of pollution may never be known. But a 129-acre farm field diagonally across the road from Alford’s trailer received more than 340 tons of sludge between 2006 and 2014, EPA records show. It was one of three sites government regulators say received the heaviest amounts of Galey and Lord sludge.

The acreage is part of the W.J. Davis farm, records show.

“They was hunting a place to put it,’’ said farmer Winfred Davis who remembers industrial plant representatives approaching him years ago about taking the sludge. “And I give them permission. And DHEC OK’d everything. That’s as good as I can tell you.’

Davis, 88, said DHEC has told him there is nothing to be concerned about and he has records from the agency verifying that.

Sludge factory

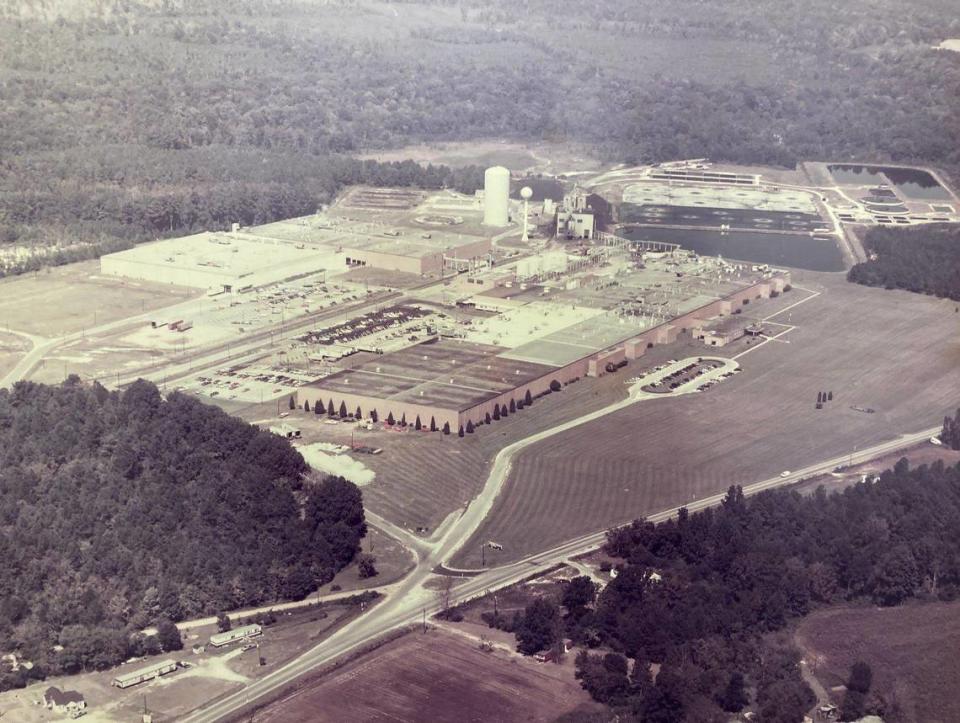

Perched on the banks of the Great Pee Dee River, the more than 700,000 square-foot Galey and Lord textile plant opened in 1966, featuring a complex of manufacturing areas that dyed and finished fabric for eventual sale in stores.

The plant, initially a division of a national textile corporation called Burlington Industries, had been a source of local pride and enthusiasm after company officials announced in 1965 that Burlington would build the factory. Initially, the company said it would employ nearly 400 people, with the prospects of hiring up to 800 eventually, The State newspaper reported in a March 25, 1965 story.

Then-Gov. Robert McNair said Burlington was the type of company South Carolina needed, The Columbia Record reported. Local officials were equally delighted, noting that the town’s only industry, a lumber mill, had burned to the ground in 1964.

“This is a thing we had hoped and looked forward to for a long time,’’ Society Hill Mayor A.B. Dailey Jr. said at the time. “I don’t know of a better type industry to fit our needs.’’

Through the years, the Burlington plant — known until 1987 as Klopman Industries — hummed along.

But environmental troubles were building, and by 1988, not long after Galey and Lord acquired the factory from Burlington, those problems surfaced.

That year, a toxic solvent — called TCE — was discovered in groundwater beneath the plant, foreshadowing a host of financial and environmental issues. The solvent, which can cause kidney cancer, contaminated groundwater that flowed toward the Great Pee Dee River, a waterway full of fish that subsistence anglers depended on for meals.

From 1992 to 2008, DHEC fined Galey and Lord $137,400 for 13 separate enforcement cases focused on air and water pollution. That put Galey and Lord in a dubious category: DHEC had fined the company more times than all but 14 others sanctioned for violating environmental laws from 1990 to 2013, The State reported in 2013.

Among the DHEC fines were sanctions for failing to keep pollution levels within approved limits before discharging treated wastewater to the Great Pee Dee River.

One agency enforcement order from 1992 said DHEC discovered “increasing’’ problems with how the company was handling sludge, the semi-solid waste material that was to be spread on some 10,000 acres of farmland in the area as fertilizer.

With environmental troubles plaguing the plant, the company signed a voluntary cleanup contract in 2013 with DHEC, pledging to resolve lingering groundwater contamination that had been found years earlier.

The plant shut down three years later and the cleanup contract was terminated in 2017 because Galey and Lord failed to complete the cleanup work, according to the EPA.

Efforts by the newspaper to reach Galey and Lord’s last six chief executive officers were unsuccessful. Attorneys involved in the Galey and Lord bankruptcy also could not be reached.

Conflict at DHEC

Despite DHEC’s knowledge about multiple environmental problems that began in 1988 and extended to 2008, the agency gave Galey and Lord permission from 1993 to 2013 to spread sludge from its waste treatment system on agricultural fields as fertilizer.

South Carolina does not forbid the use of sludge containing PFAS and the idea of putting waste material full of nutrients on crops made sense, government officials said at the time.

Farmers wanted the sludge — and an official with Clemson University supported using the sludge for “hay and pasture crops,’ according to a 1995 memo from Bio-Nomic Services, a contractor that worked for Galey and Lord.

A 2000 renewal application report offered similar assurances, saying the spots where sludge would be applied “are more than adequate to handle biosolid generated over the next several years.’’

The document, obtained by The State under an open records request, said nothing about forever chemicals. DHEC conceded in a 2020 drinking water strategy report that sites taking sludge from treatment plants “could contain PFAS.’’

Bob Guild, one of the state’s most experienced environmental lawyers, said DHEC should have kept a better eye on Galey and Lord before approving the sludge disposal requests.

The $137,000 in fines Galey and Lord was assessed, while not related to PFAS, should have given DHEC some clue as to how the company operated, he said.

“That ought to be a red flag to let the farmers know so they can exercise some prudence in deciding whether to take the sludge in trade with the company,’’ Guild said.

William Evans, who worked for a Galey and Lord contractor, said the sludge disposal business was an unpleasant one with its share of hazards.

To make the sludge available to farmers, contract workers at Galey and Lord would suck the material from a waste lagoon, he said. Tanker trucks would then leave for farm fields, said Evans, who worked on a dredge that vacuumed up the sludge.

On several occasions, Evans, 55, fell off the dredge boat that was vacuuming sludge from the bottom of a Galey and Lord lagoon. The sludge smelled horrible and reminded him of black tar.

“It was just a really nasty job,’’ he said, noting that the sludge “was rough on the equipment. It like decayed the metals and equipment, rusted it out.’’

Evans said the sludge did not appear harmless to him, but Bio-Nomic Services told him it was good for crops.

An official with Bio-Nomic Services, which lists an address in Belmont, N.C., said the company couldn’t say anything about sludge spreading in Darlington County because “there’s nobody here that worked here 30 years ago.’’ The official, Kiki Melson, also questioned whether the company was involved.

Meanwhile, some Darlington residents are using the court system in search of answers.

Kim and Jamie Weatherford, who live a few miles away from the O’Neals, have filed lawsuits in state and federal court against Galey and Lord and the manufacturers of PFAS, Dupont and 3M, that provided the material to the textile plant.

Former Democratic state Sen. Vincent Sheheen, a lawyer from Camden who represents the Weatherfords, said the family and neighbors need help.

“What happened is flat out wrong,’’ said Sheheen, who also has been hired recently by state Attorney General Alan Wilson to handle PFAs legal cases on behalf of the state. “ When I visited these families, it made me very angry.”

The couple says their 22-year-old son is so fatigued at times that he can’t get out of bed. His problems began in high school after several years of drinking water from what later was determined to be a PFAS-polluted well, they say.

In addition, the couple says a family dog chewed up a used PFAS filter in their yard. The animal died soon afterward.

“It’s pretty out here and it’s peaceful and we love it,’’ said Kim Weatherford of the rural Darlington County community where her family has lived for the past decade. “But there are things happening you don’t think of. This is the last thing I’d ever have dreamed of.’’

The lawsuits allege, among other things, the manufacturers knew the dangers of forever chemicals but still distributed the material to the plant for use in its dying and finishing process.

Representatives of DuPont and 3M have said in court papers they are not to blame for any problems cited in the Weatherford’s lawsuit.

Recently, the 3M company reached a $10.3 billion settlement with cities across the country over claims it polluted their drinking water, according to The New York Times.

It’s all a concern for the O’Neals, who like many other farm families, trusted an industrial plant’s offer to give them free fertilizer.

“If it’s free, there’s got to be something wrong with it,’’ Robbie O’Neal said. “If they are paying that much to truck it to you and to spread it, there was something in it for them.

“But not for you.’’

Acknowledgements

Gina Smith | Editor

Joshua Boucher and Tracy Glantz | Photography and video

Rachel Handley and Sohail Al-Jamea | Illustration, animation and video

Gabby McCall | Logo design

Susan Merriam and David Newcomb | Data visualization and development