SC gives medical contracts to crisis pregnancy centers. Lack of regulations raise concerns.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Much of South Carolina's abortion debate has hinged upon the push and pull of a six-week abortion ban and the Republican dispassion for the medical procedure.

But lesser known is the faith lawmakers rest on organizations they see as the alternatives to abortion care.

In court filings, budget documents and policy discussions, public officials repeatedly insisted pregnant people had other options, and preferred culling financial support for abortion providers like Planned Parenthood.

In the last state budget, lawmakers fueled that notion by giving nearly $2.6 million worth of medical contracts to anti-abortion, crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs). This year, lawmakers gave nearly the same amount of funding to CPCs, but turned it from one-time funding to recurrent funding in the state budget.

S.C. Department of Health and Human Services reports show about 20 organizations across the state received funding to hire nursing staff, fund counseling services and run a maternity home.

These non-profit organizations are faith-based and encourage individuals against ending their pregnancy. They offer programs for families to access diapers, counseling, free pregnancy tests and limited ultrasounds. Many even offer free STI testing and assist with adoption services.

But that's not the extent of their efforts. These spaces are platforms for public officials and presidential hopefuls to seek endorsements and brandish their pro-life track record.

In 2021, Susan B. Anthony List, a prominent anti-abortion group, announced its support of Gov. Henry McMaster’s re-election campaign at Greenville’s Piedmont Women’s Center.

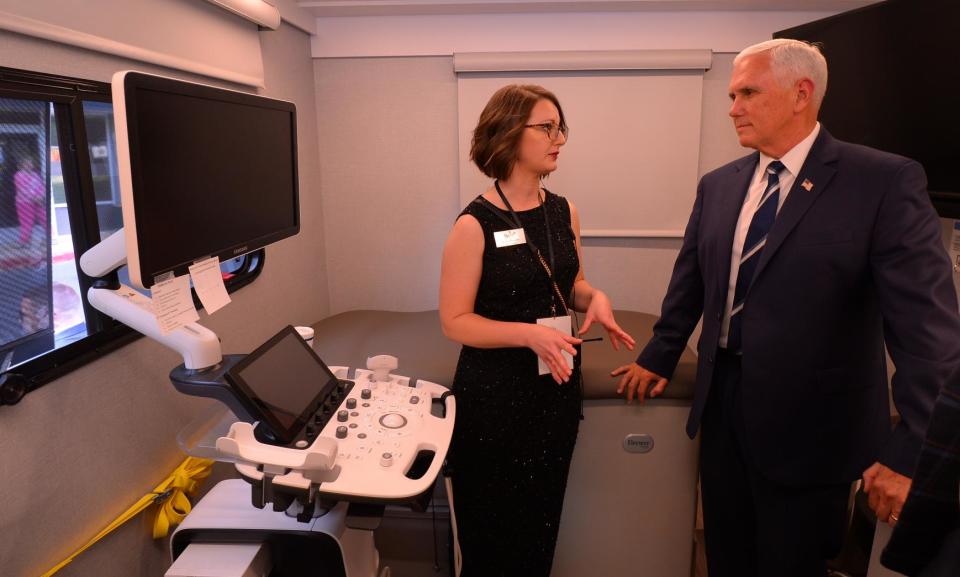

Last year, former Vice President Mike Pence visited Spartanburg and spoke at a gala hosted by the Carolina Pregnancy Center. Pence's visit came the same week a draft leak of the U.S. Supreme Court's majority ruling signaled the court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

"This has been a momentous week in the cause of life. I believe with all my heart that life is winning in America. To be pro-life you must be pro-adoption," Pence said in Spartanburg.

Ardent supporters are confident in the mission of South Carolina anti-abortion centers to protect mothers and infants in a state battered by a maternal health crisis, which disproportionately affects low-income, women of color.

But public health experts are concerned about the quality of medical services offered at CPCs. Unlike other organizations that purport to offer medical services, these centers remain vastly unregulated and do not face the same oversight other medical spaces do.

Experts argue they merely mimic other healthcare organizations and can mislead pregnant individuals with abortion misinformation, often exaggerating the procedure's effects and downplaying the risks of delivering a child, which is considered to be 14 times more dangerous than getting an abortion.

A set of guidelines from Care Net, an organization many CPCs are affiliated with, deter single people from using contraception and recommend that married couples seek contraceptive advice from their pastors or physicians.

Meanwhile, faith-focused counseling, which could delay a pregnant individual from getting critical healthcare on time, rarely match nationally accepted medical standards supported by organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

"They're not medical facilities and they have very specific goals — anti-abortion, promoting sexual abstinence before marriage, and promoting marriage," said Andrea Swartzendruber, professor at the University of Georgia College of Public Health said. "So they're not taking a client-centered approach of prioritizing the client's needs. They are prioritizing their own goals, which I think is in conflict with all public health and medical frameworks."

How does SC's budget fund crisis pregnancy centers?

Lawmakers made three allocations in the 2022 budget.

A total of $50,000 went to the Pregnancy Center and Clinic of the Lowcountry to hire a professional nursing staff. St. Clare’s Maternity Home, associated with the Charleston Diocese, received $200,000 for counseling, occupancy and food expenses.

The biggest recipient of funding was the SC Association of Pregnancy Care Centers, a group of 19 organizations that received over $126,000 each. Prominent Upstate-based centers such as Carolina Pregnancy Center and Piedmont Women's Center are part of this coalition.

This year, crisis pregnancy centers were awarded $2.4 million, again, under medical contracts, and the Pregnancy Center and Clinic of the Lowcountry also got another $50,000.

Rep. Bill Herbkersman, R-Beaufort, who earmarked $50,000 for the Pregnancy Center and Clinic of the Lowcountry, said addressing maternal health after the fall of Roe v. Wade was the "genesis" of his earmark. He had seen CPCs offer prenatal vitamins and care for families coming to terms with unintended pregnancies.

"There's no system that's perfect," Herbkersman said. "Some of these women are as young 14 to 15 years old — teaching them how to care for a child and how to care for themselves too ... I think that's critical, and that's their mission.”

This type of funding is not unique to South Carolina. Earlier this year, Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee attempted to divert $100 million to anti-abortion CPCs. That amount was later whittled down to $20 million. Meanwhile, in 2022, Texas gave $100 million to its state program supporting abortion alternatives for a period of two years.

Herbkersman, also a member of the influential House Ways and Means Committee, said it was unlikely that SC would fund anti-abortion programs like Tennessee and Texas due to budgetary reasons. Several maternal and infant health-related services are covered by Medicaid.

"But I do think that in areas where (CPCs) are helping and we can prove the metrics on it, then it deserves to be looked at and serves to be properly funded," he said.

Reproductive rights advocates question correlation between crisis pregnancy centers, improved maternal health

In South Carolina, 14 of 46 counties don't have a dedicated OB-GYN doctor.

Lack of transportation resources often leaves patients in dire straits. Some women are forced to drive for hours between facilities that offer prenatal or post-partum care. A recent maternal mortality report showed 82% of the pregnancy-related deaths recorded in 2019 were preventable if patients had access to critical care.

"Anti-abortion centers exist in every single state," said Ashley Underwood, director at Equity Forward. "Red and blue, progressive bubbles, they're everywhere."

But the presence of anti-abortion centers has not curbed a rise in the number of maternity care deserts — spaces in the U.S. without a hospital or birth center offering critical healthcare.

Underwood said there is a need for improved social infrastructure that caters to child care. She sees the allure of anti-abortion centers that advertise free services, counseling and parenting courses as a resource.

"I'm a parent as well. I think most people would jump at the opportunity to have some sort of course that helps direct their parenting journey," she continued.

But anti-abortion centers are generally not equipped to address wages, jobs and the full spectrum of child care costs, she said.

Vicki Ringer, Director of Public Affairs for Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, said lawmakers could improve key metrics by expanding Medicaid and increasing funding for community health centers. Ringer said lawmakers could also recruit more doctors by creating a model where the government could offer paying student loans in exchange for doctors making a commitment of working in a particular area for at least five years.

"There is so much that they can do,” Ringer said.

What to know about crisis pregnancy centers in SC

Charleston, Columbia and Greenville have the only three abortion clinics, currently, in SC.

There are more than 35 crisis pregnancy centers operating in the state, according to a crisis pregnancy center map created by Swartzendruber and Danielle Lambert at the University of Georgia College of Public Health.

The News reached out to each pregnancy center that received state funding with questions about their services. The News also reached out to other crisis pregnancy centers in the state.

Only one representative responded.

"The South Carolina Association of Pregnancy Care Centers (SCAPCC) consists of some 20-plus member centers that provide complimentary support services, medical care and physical resources to pregnant women, their partners and their babies," Cassandra Deans, SCAPCC President said. "The state funds received are being used to enhance and continue these services."

Experts: medicalizing crisis pregnancy centers may pose a public health risk

Swartzendruber and Lambert have been researching anti-abortion centers since 2018 and have tracked their evolution.

They believe the SC legislature's decision to give medical contracts to anti-abortion centers is part of a movement to "medicalize" crisis pregnancy centers to help CPCs escape scrutiny.

Their research shows CPCs became more medicalized with each passing year between 2018 and 2021. They began with the first step: offering free, yet limited, ultrasounds.

In 2018, 66% of the CPCs offered a free ultrasound. That figure jumped to 77% in 2021. Though seemingly well-intentioned, limited ultrasounds can be a cause for concern for expecting mothers.

Lambert said limited ultrasounds are aimed toward confirming a pregnancy and the pregnancy's term. But ultrasound technicians in CPCs, who aren't required to be licensed in South Carolina and 45 other states, are not looking for complications that could arise during pregnancy.

"It's not always clear to everyone that (a limited ultrasound from a CPC) is not the same type of ultrasound that they would get from an OB-GYN," Lambert said.

She raised the case of a lawsuit in Massachusetts that originated when a pregnant woman visited a crisis pregnancy center for an ultrasound. The ultrasound technician confirmed she was in the midst of a viable, healthy pregnancy. However, a month after her visit, it was revealed that she had an ectopic pregnancy that required emergency surgery.

"So who's at fault? Should the tech have caught that?" Lambert asked. "When CPCs use that terminology around limited ultrasound — it's not fully exploring all the potential complications. It's not prenatal care."

Down South, home to 40% of the CPCs in the U.S., Reveal investigations documented incidents in Kentucky and Florida, where CPCs either did not disinfect transvaginal ultrasounds properly or told a patient incorrectly that an abortion might lead to breast cancer.

Other medical spaces, such as a hospital system or an abortion clinic, undergo extreme scrutiny when it comes to licensing and safety standards for both patients and workers. The Dept. of Health and Environment Clinic, a regulatory body, also licenses tattoo and body piercing facilities.

But the rules are not the same for crisis pregnancy centers, a review of the state law showed.

"People may be going to CPCs thinking that they're getting first trimester, early second-trimester prenatal care. So they're not seeking out an OB-GYN because they think that they're getting that for free at a CPC," Lambert said. "But that's not a substitute for licensed medical advice. That's not a substitute for a full-range ultrasound."

Rep. Chandra Dillard, D-Greenville, said the lack of oversight worried her.

"If something is being couched as a medical facility, there needs to be some uniformity," she said. The public has perceptions and expectations when they walk into the facility, and so if we're giving public funds, we need to make sure that those expectations are met."

Devyani Chhetri covers SC politics for the Greenville News. You can reach her at dchhetri@gannett.com or @ChhetriDevyani

This article originally appeared on Greenville News: SC gives medical contracts, funding to crisis pregnancy centers