SC’s Haley touts taking down the Confederate flag, but how important was her role?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Eight years ago this week, the Confederate flag that had flown on the S.C. State House lawn for 15 years was lowered for good, forever changing the landscape of the landmark house of government in the heart of South Carolina.

It was part of the state’s response to the June 17, 2015, shooting at Charleston’s historic Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church, where nine Black churchgoers, including state Sen. Clementa Pinckney, were killed by a self-avowed white supremacist in a hate-driven act of violence. The story of how the state responded to the infamous shooting is one Republican presidential hopeful Nikki Haley, who was the state’s governor at the time, now refers to in her campaign for the White House.

During her time as governor, the flag had flown for more than four years, and she never broached its removal before it was displayed as a symbol of hatred by the white supremacist who carried out the Emanuel shooting. She, like most state leaders for years before her, publicly shied away from the divisive subject, which had a tendency to rile voters even as national groups including the NAACP and the NCAA boycotted the state over the flag’s flying.

Now, when she gets questions on the campaign trail about how to bring people together, Haley discusses the state’s response to the church shooting and the removal of the flag. But the question rises: How key was Haley’s role in bringing the Confederate flag down?

Some state leaders from the time say Haley’s “bold” position on the flag ultimately provided cover for lawmakers to act, though others recall that movement was happening with or without her.

In the days following the Emanuel shooting, as the former South Carolina governor came to her own conclusion that the Confederate flag needed to go, state lawmakers were independently working on a parallel track, as they say they had discussions about what to do with the flag before Haley gave State House leaders a call.

But before the shooting, Republicans in the General Assembly resisted even discussing removing the flag from the State House grounds, placed there behind the Confederate soldiers memorial as part of a compromise in 2000 that had brought the flag down from the capitol dome.

In a state where much of the control lies with legislators, Haley’s largest asset in the post-Emanuel flag debate was the bully pulpit. She wielded her platform at a news conference five days after the Charleston shooting to call the removal of the Confederate flag.

Ultimately, the deaths of nine Black people at last moved state leaders to bring the flag down on July 10, 2015.

Haley did not call for flag removal before shooting

Haley did not plan to make the Confederate flag a signature issue of her tenure as governor. And over the years, she has both defended the flag as a symbol of Southern history and heritage, and argued the flag was hijacked by the church shooter as a symbol of racist hate.

When she first ran for governor, Haley had no interest in removing the flag from the State House grounds. She even told the Sons of Confederate Veterans that she would talk to groups critical of the flag to say that it represented Southern heritage and wasn’t racist.

In 2014, when former state Sen. Vincent Sheheen, a Kershaw Democrat who was running against Haley in her reelection bid, called for the flag to be removed, Haley’s office said, “If the General Assembly wants to revisit the issue that’s fine. But any such effort should be done in a thoughtful bipartisan way and not in the heat of the political campaign season.”

Haley later said in a debate that she had not had any conversations with corporate CEOs about the flag, as she highlighted efforts to recruit companies to locate in South Carolina and create jobs in the state.

After the Emanuel shooting and the appearance of the shooter’s white supremacist manifesto, Haley shifted her stance on the flag whether the flag should continue to fly.

During a recent town hall on CNN, Haley said she was worried at the time that the state would fall apart as the Emanuel shooting happened after the Ferguson, Missouri, riots and protests and the Walter Scott shooting in North Charleston, which led to a requirement for law enforcement to wear body cameras in the state.

“The national media came in, and they wanted to make it about race; they wanted to make it about the death penalty; they wanted to make it about guns. And I strong-armed them at the time and I said, ‘There will be a time and place we can have those debates, but right now we need to put to rest nine amazing souls.’ And I tried to protect that,” Haley said when asked about how she could do better than the divisive tone seen in the nation’s politics today. “I didn’t have that luxury, because a couple of days later the murderer came out with his manifesto, holding the Confederate flag.”

Three days after the Emanuel shooting, Haley said she spoke to her husband, Michael, about how she felt the flag couldn’t fly anymore, and Haley told her staff to set up meetings with Democratic leadership, Republican leadership, the federal delegation and community leaders the Monday after the shootings.

“And I said, ‘Don’t tell them why I want to meet, because I knew they wouldn’t come. And when those meetings happened, I said to them, ‘At 3:00 today, I’m going to ask for the Confederate flag to come down. If you will stand with me, I will forever be grateful. And if you won’t, I’ll never tell anyone you were in this room. And I’ll never tell about who dissented,” Haley said during the CNN town hall.

Why not sooner?

Discussion of removing the flag was the equivalent of grabbing the third rail in South Carolina politics.

In the days following the shooting and before Haley held her news conference, calls from Republicans were being made to bring down the flag, including from Mitt Romney and Jeb Bush and then-state Rep. Doug Brannon, who said he planned to file legislation to remove the flag.

But it was a compromise from 15 years earlier — and a lack of movement since then — that had left state officials to deal with the flag now.

In 2000, lawmakers came to agreement to remove the Confederate flag from atop the State House dome, where it had flown since 1961, and from inside the two legislative chambers. In return, lawmakers agreed to place a Confederate flag along Gervais Street in front of the capitol as part of the Confederate soldiers memorial and to build an African American monument on the State House grounds.

“There probably was a push to take it off the grounds completely, but up there (in the State House), it’s the art of the possible,” said state Sen. Tom Davis, R-Beaufort, who is backing the Haley campaign. “At that point in time, that was as far as they could go. I don’t think it was a mistake in the sense of there was an opportunity to remove it completely and that opportunity wasn’t taken. I just don’t think the political situation at that time provided that opportunity. I think they got all they accomplished that they could.”

And a single senator could have blocked the 2000 flag compromise from moving forward and kept the flag flying prominently on the dome, especially as many Republican lawmakers for a long time believed the flag was a symbol of Southern heritage.

“I don’t know how you could have gotten more done,” Davis said.

Some lawmakers believed it was best to stand by that bargain and leave the flag alone where it stood from 2000 onward, Davis said.

Senators including Davis and former state Sen. Larry Martin, a Pickens Republican who lost in the 2016 primary to Rex Rice, said Haley was key to bringing down the flag in 2015.

Martin said while senators were grieving over the shooting and the loss of one of their own colleagues, many in the chamber didn’t didn’t want to make any move right off the bat.

But Haley’s call for the flag to come down moved the Senate to take action, Martin said.

“She took a bold position on it. I think it resonated with a lot of members,” Martin said. “I don’t think there’s any chance it would have passed. I don’t think we would have taken it up had she not took the position that she did.”

Davis was more blunt.

“There was not the political will among leadership, there was not the political will among Republicans in the state Senate to go ahead and touch this rail and put their neck out there and to sign on to a resolution to remove the flag and amend the sine die to allow it to be taken up until she stepped in and provided that cover,” Davis said. “I am adamant about that.”

Discussions taking place without the governor

But after the Charleston shooting, discussions were happening among lawmakers in both chambers independent of Haley.

State Sen. Darrell Jackson, a Black Richland Democrat who had been a longtime advocate for removing the Confederate flag from the State House grounds, said he was involved in calls with Senate leadership immediately after the shooting. One of those conversations was with the late Sen. Hugh Leatherman, a Republican who was Senate Finance chairman and the most powerful lawmaker in the State House.

“One conversation I will never forget is the conversation with Hugh Leatherman,” Jackson recalled. “He said, ‘As tragic as it was to lose our colleague and eight other people, in the end, this may be what is necessary,’ because I talked to him about that.”

Jackson said there was movement in the Senate.

“I don’t doubt that Nikki Haley and her office heard about that and they wanted to be a part of it,” Jackson said.

While legislators were discussing how to move forward, Haley comforted victims’ families and had discussions within her own inner circle, said Rob Godfrey, who served as Haley’s deputy chief of staff.

“Legislators were deeply impacted by the unspeakable tragedy and loss of a colleague, and no doubt immediately discussed how to respond among their leaders,” Godfrey said. “But I also know firsthand the governor, herself deeply impacted by the immeasurable loss and determined to focus on the victims and their families, turned to a close circle of people with whom she talked in that immediate aftermath and kept her conversations to her husband and a very small group of staff.”

According to lawmakers involved in House leadership at the time, legislators were already working on how to move forward, which included options such as lowering the Confederate flag at the Confederate soldiers memorial to half staff out of respect for the Emanuel victims and then ultimately replacing the flag with another battle flag of South Carolina’s First Regiment.

Senators eventually passed a bill to remove the flag and the pole so no other flag would fly.

But some in the House at the time also considered leaving the pole up, an idea Haley disagreed with.

“I had been in the South Carolina Legislature; I knew what that meant,” Haley said during her recent CNN town hall. “That meant that as soon as the flag came down, another flag was going to go up after the national media went away.”

House leadership had to keep their members in line to stop amendments from being added to the Senate’s bill, which could have either forced the Senate to return or potentially cause a delay in the flag’s removal.

In order to even get to a debate on the Confederate flag, from a procedural perspective, lawmakers had to first change a sine die agreement, which stated what they could work on after the formal end of the year’s legislative session, a move requiring a two-thirds vote of each chamber. Those votes took place a day after Haley’s June 22, 2015, news conference calling for the removal of the flag.

Then each chamber still needed a two-thirds vote of approval to take down the flag, a requirement from 2000 compromise law, formally known as the Heritage Act. The law required the same approval for any Confederate or war memorials to be changed anywhere in the state. In 2021, that two-thirds requirement was struck down by the state Supreme Court.

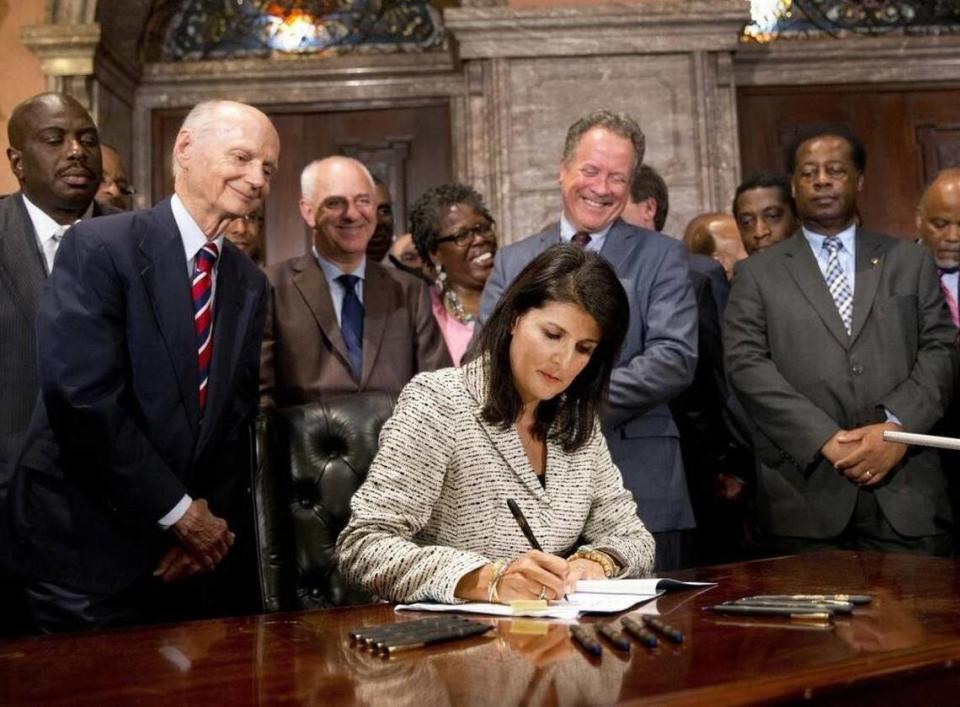

But the two-thirds threshold on each of those votes was met, as the Senate voted 37-3 and the House voted 93-27 before Haley signed the bill to remove the flag.

“I had conversations with senators and with the Speaker of the House prior to the governor coming around on the House bill, that we were going to take the flag down, and that was because we had to two-thirds to do it,” state House Minority Leader Todd Rutherford, a Richland Democrat, said in an interview last month. “We knew what our plan was, and we were going to do it, and that was prior to getting a call from the governor’s office to come and meet with her, because she had at that point agreed to help and not be a hindrance in taking the flag down.”

State House leaders said much of their motivation to move forward came from the desire of the family of Emanuel pastor and state Sen. Clementa Pinckney, who was killed in the Charleston shooting, to see the flag removed.

State Rep. Bruce Bannister, a Greenville Republican who was House majority leader at the time and who is now backing U.S. Sen. Tim Scott’s presidential campaign, said the votes were there to take the flag down even without Haley’s call to take down the flag.

“She did assure us that it would not be vetoed,” said Bannister, who added that the governor’s promise made a difference.

Bannister said Haley was in a position to stop the flag from coming down if she wanted to or could have lobbied for an alternate solution.

“So give credit where credit’s due,” Bannister said. “She saw the political opportunity to take the flag off the State House grounds and be done with it. But was she the exclusive leader in making that happen? I would say it was the senator’s family. They were the impetus.”

Haley provided a ‘calming influence’ after shooting

At the very least, Haley’s public call to remove the flag provided cover for reluctant Republicans who wanted to keep the flag flying on the grounds. For those around Haley, they say she also provided care to victims’ families immediately after the shooting.

“Gov. Haley held South Carolina together in the wake of one of the most tragic moments in state history. Her job was to protect the state and heal its wounds. Gov. Haley’s leadership in helping bring down the Confederate flag is well-documented,” said Ken Farnaso, spokesman for Haley’s presidential campaign.

The Charleston shooting and subsequent debate over the flag took place less than four months after Walter Scott, a Black man, was fatally shot by a white North Charleston police officer, and nearly a year after the killing of Black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, at the hands of a white police officer.

“I think when you look at the set of circumstances from April to July of 2015 and what was happening in other parts of our country, some potentially bad things could have happened in our state,” said James Burns, who was Haley’s chief of staff at the time. “But I think Gov. Haley’s leadership during that time was a calming influence, and that was an extraordinary exercise in leadership.”

“No one individual could take the flag down. That was just the nature of the statute. It took the work of multiple constituencies, but, again, her leadership in that time of crisis in our state was significantly important,” Burns said.

After the flag came down, Haley was praised for her efforts, even by those who criticize her today.

“I give her credit for stepping out there and doing what’s right,” Rutherford told the Associated Press in 2015. “I wish it had been done a long time ago.”