Is SC punishing people as drug dealers who aren’t? New bill wants to ensure state doesn’t

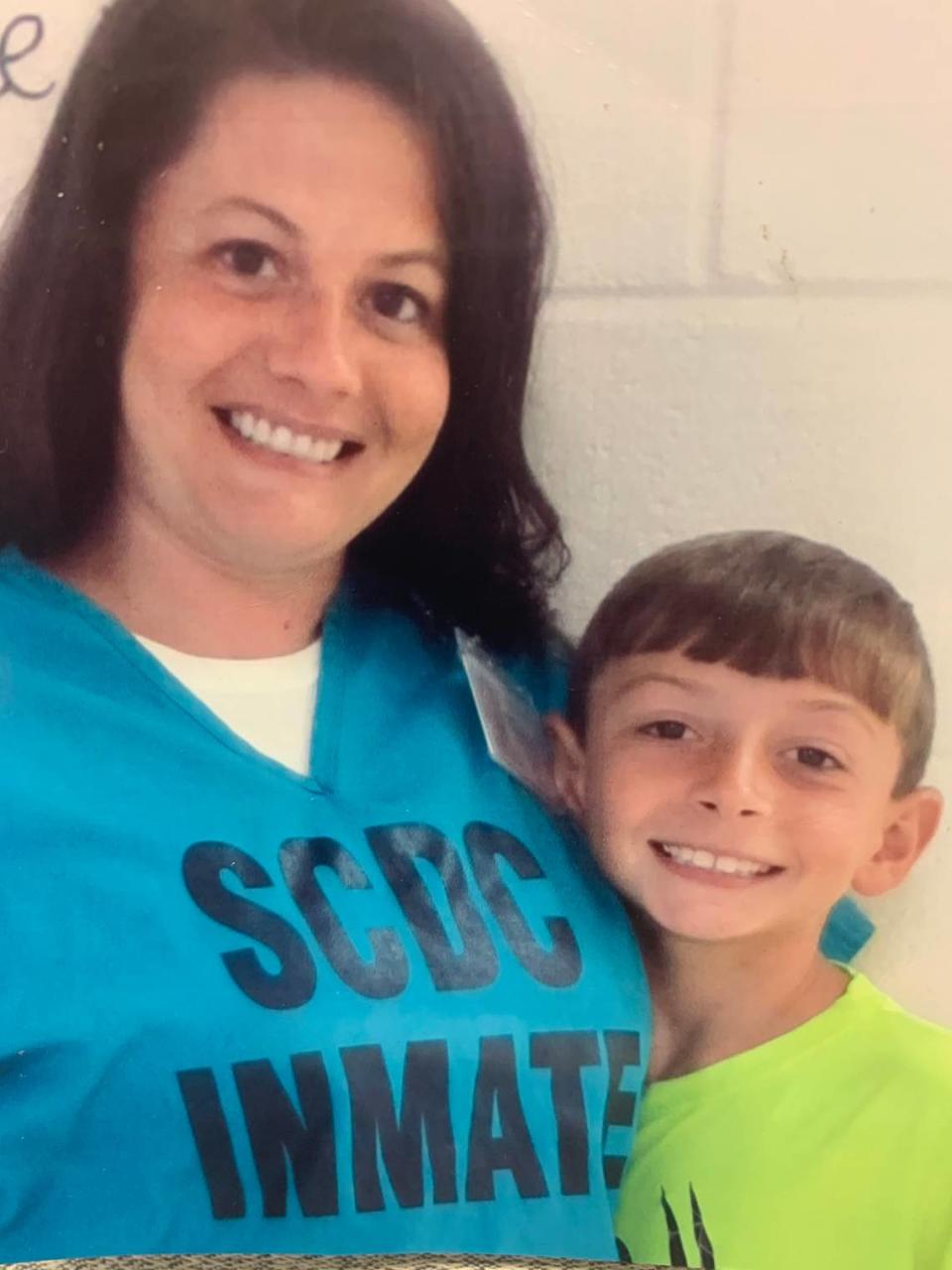

Kerrie Wilson was in love, according to court testimony. But soon the man she adored would lead her to being in prison.

Her mistake was loving a bad person, said Rose Wilson, Kerrie’s grandmother, but that isn’t a crime. What landed her granddaughter in prison was an unfair and dated South Carolina law that requires a minimum sentence and forces judges to send too many people to jail, Wilson said.

“She was a victim of circumstance,” Wilson said.

A bipartisan bill, which passed an S.C. House subcommittee Thursday, proposes to change so called “mandatory minimum” sentences and “no parole” drug offenses. Georgia empowered judges to bypass minimum sentences as well as North Carolina in June 2020.

Other states, including Alabama, have enacted laws or are working on changes to give judges drug sentencing discretion and to end or lower mandatory minimums. The South Carolina bill would also shorten the time people convicted on drug offenses must remain behind bars. The bill is now awaiting approval of the House Judiciary Committee.

“These charges will still carry decades of prison time but this change will simply allow duly elected judges to make the decision on what someone should receive by taking into account the mitigating circumstances present in one’s life,” said Rep. Seth Rose, D-Richland, an attorney who is a co-sponsor on the bill and helped pass it out of subcommittee.

Dorchester County Republican Chris Murphy, chairman of the House judiciary committee, sponsored the bill and other GOP members signed on, including House Speaker Jay Lucas of Darlington County.

The South Carolina bill follows federal legislation. In 2018, former President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act, which reduced federal mandatory minimums for drug offenses and allowed U.S. judges to sentence certain defendants to less than the minimums. He touted that the law helped end racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

As is, South Carolina laws require a minimum number of years in prison if a person is convicted of drug trafficking, the most severe drug crime in the state. In the 1990s, lawmakers enacted the rules to punish dealers selling large quantities of drugs and to get them off the street.

That purpose has been lost though, said York County Public Defender B.J. Barrowclough, and people with substance use issues or otherwise decent people caught in bad situations are being unjustly punished. The sentences are absurdly high in some cases, and the amount of drugs needed for trafficking charges are far too low, making South Carolina out of step with drug laws across the country, according to Barrowclough.

Before Kerrie Wilson faced a mandatory minimum prison sentence, she had been an ideal granddaughter and mother, her grandmother and defense attorney told the court in 2019. The daughter of a welder, Kerrie had grown up and worked in the store her grandmother owned in Laurens County, never getting in any trouble in her life, Rose Wilson said. In 2018, she was raising her two kids — both were doing well in school — and had a job with an organization that cared for mentally disabled children. But for the six years prior, her kindness and caring had been taken advantage of by a man.

He was in prison for drugs and wanted someone to talk to, a friend told Kerrie. She started talking to him daily and visiting him weekly and, against her family’s advice, she continued the relationship when he got out of prison. It wasn’t long before he became abusive, Rose Wilson said.

Kerrie thought he might kill her if she crossed him the wrong way. Wilson said her granddaughter was “brainwashed” by the man, whose drug habit — which had put him in prison — quickly returned.

In May 2018, a Greenville deputy stopped her boyfriend for speeding, court records showed. Another man was in the car and Kerrie was in the backseat. The deputy smelled marijuana, and police searched the car. They found meth, marijuana and a digital scale in Kerrie’s purse. Unbeknownst to Kerrie, her boyfriend or the other man in the car had put the drugs and scale in her purse, Wilson said.

Police charged Kerrie with three drug offenses including meth trafficking, the kind of charge meant to get dealers off the street.

The woman who had no prior record and a mother of two faced a decision. She could plead guilty and accept the mandatory minimum of seven years in prison, or she could go to trial and risk a maximum 25-year prison sentence.

Mandatory minimums strip people of their right to a trial by setting up outrageous choices like Kerrie encountered, advocates for changing the laws said. People rarely choose a jury trial, which, essentially, makes prosecutors determine a sentence instead of a judge.

South Carolina’s current drug trafficking laws also don’t allow judges to sentence people to probation or set aside years behind bars in lieu of another punishment.

The House bill seeks to fix these issues by ending all mandatory minimums for trafficking charges. The bill also lets judges choose probation or a suspended sentence. Lawmakers also propose lowering maximum sentences for most drug charges too.

The bill increases the amount of drugs a person must possess to be charged with selling or trafficking. With current law, a person can be charged with selling marijuana — and face a maximum 20 years in prison — for having just more than an ounce. The new law requires a person to have at least 10 ounces of marijuana to be charged with selling, and the new maximum would be ten years.

South Carolina’s laws regarding how much of a drug a person must possess to be charged with trafficking are much lower than those in nearby states.

In Georgia, a person is charged with trafficking when they’re holding 28 grams of cocaine. In South Carolina a person can be charged with trafficking for have 10 grams.

Mandatory minimums are used to discourage defendants from scrutinizing evidence gathered by police, advocates for changing the law said. When plea deals are being worked up, prosecutors will threatened to take away a deal for the minimum sentence if defendants ask to see police-gathered evidence against them.

“That encourages sloppiness if not down right police misconduct,” Barrowclough said.

If the proposed law was in place in 2018, Kerrie would have been charged with a lesser trafficking offense, the seven-year minimum wouldn’t have exist, her maximum sentence would’ve been 10 years instead of 25, and a judge could have sentenced her to probation.

In 2019, Kerrie pleaded guilty to meth trafficking and was going to accept the mandatory minimum sentence. But a judge believed the sentence was too harsh and refused to sentence, according to her defense attorney, Richard Warder of Greenville. Hamstrung by the current law, all the judge could do was forgo sentencing and put it into another judge’s hands at a later date.

Warder doesn’t believe mandatory minimums are right for reasons like Kerrie’s case.

“They take discretion away from the trial judge and he can’t consider all of the options,” Warder said.

Effects

Brenda Murphy, president of the South Carolina Conference of the NAACP, supports ending mandatory minimums and giving judges discretion.

Not requiring a prison sentence would allow people with drug use issues to be placed into treatment, she said. People with substance abuse problems often suffer with mental health issues that shouldn’t be treated as crimes, she said.

Any criminal justice reform is monitored by the NAACP’s South Carolina Conference because of the well-documented disproportionate effects of the system on Black people.

“When it comes to prison reforms there’s a lot to do in our state to make sure sentences are equally applied,” she said.

Study after study have concluded that mandatory minimums disproportionately affect Black people across the United States.

The bill “is a positive and vital step in the direction of fulfilling the promise of the Equitable Justice and Law Enforcement Reform Committee formed last year,” Fifth Circuit Public Defender Fielding Pringle said. “There is far more work to be done to address the racism inherent in our justice system but this is movement in the right direction.”

The Fifth Circuit includes Richland and Kershaw counties.

In August 2020, a coalition of state public defenders recommended ending mandatory minimums and giving judges sentencing discretion to the House’s adhoc Equitable Justice System and Law Enforcement Reform Committee.

A person convicted of murder faces a mandatory minimum of 30 years, Rose said. For certain drug cases a person can have “mere grams” of a substance and face a mandatory minimum of 25 years.

“That in and of itself is absolutely absurd and the data suggests this is being overly enforced in minority communities,” he said.

Current South Carolina law categorizes drug trafficking as a violent crime. If convicted of a violent crime a person cannot get parole. Convicted people have to serve 85% of a sentence in prison before being released and supervised. The bill would change the time that people convicted of drug trafficking have to stay imprisoned to 65%.

Critics of changing South Carolina’s drug laws say undoing minimums and decreasing prison time will allow dealers back on the street. They also say that ending minimums will take away leverage prosecutors use to put dealers away.

In states like Texas, which doesn’t have mandatory minimums, prosecutors don’t face any extra barriers to convicting dealers, a study done by a group that researches mandatory minimum laws said. Mississippi, Virginia and Oklahoma all allow judges to deviate from minimums.

For critics who say that if the bill passes “all of a sudden South Carolina is going to be Sodom and Gomorrah, that’s completely disingenuous,” Barrowclough said.

Advocates for changing the law also point out that less people being imprisoned will help understaffed prisons and save taxpayers millions of dollars. But what would ultimately be saved is fairness for people like Kerrie.

A second judge sentenced her to the mandatory minimum of seven years. She’ll get out in 2024 if the law stays the same. Her grandmother hopes the new bill will pass and Kerrie can get out after 65% of her sentence in 2022.

Kerrie is the kind of person who asks for birthday cards to be sent to other imprisoned women, not someone who asks for money for drugs, Wilson said. Kerrie should have been at her first son’s high school graduation but instead she was being punished like a drug trafficker.

“Is that fair? Is that justice?” Wilson said. “It’s not.”