SC teacher’s racism lesson was shut down by book ban. But she’s still talking about it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When teacher Mary Wood stepped back into the classroom this semester, she didn’t just have the usual back-to-school jitters.

This wasn’t the veteran teacher’s first time starting a new English class, but it was the first since her lesson plan for last year put her in the center of a very public spat about how race is taught in South Carolina classrooms.

It was a discussion that she at times welcomed and at others worried how it was affecting her standing both professionally and in her community at large.

“Starting school was weird,” Wood said in an interview at her Chapin home. “I was unsure how I would be received. I don’t venture much outside the English department.”

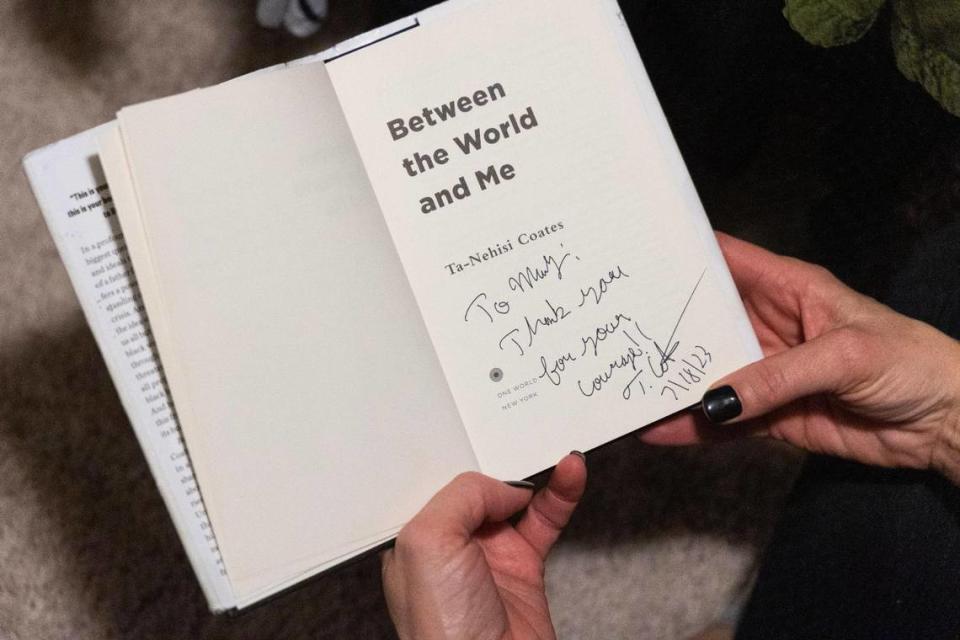

But Wood hasn’t hidden since controversy erupted earlier this year over her choice to use “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates in her advanced placement language arts class at Chapin High School. She pushed back against administrators’ decision to stop teaching the book in a letter to the superintendent and school board, and in subsequent media interviews with national and international outlets that picked up the story.

But the blowback she received was also something she had never experienced before. Community members spoke at Lexington-Richland 5 school board meetings calling for her to be fired. Her school email address, which previously just received questions from students and parents about assignments, filled up with messages from strangers telling her “they’re coming for you, you can’t hide,” and “I hope you get cancer and rot.”

Coates’ 2015 memoir takes the form of a letter to the author’s teenaged son, recapping American racial history and its impact on Coates’ life growing up Black in inner-city Baltimore.

Wood said she used the book because it fit with the course’s objective of having students engage with and analyze an argument. “It’s a really well-written book, so in addition to argument and rhetorical analysis, they get lessons in writing well from reading it, in what these rhetorical devices they’re learning look like when used in an argument.”

It’s also the kind of material that students will encounter in a college course, for which an AP class is meant to prepare them. “A college-level class is not going to be things you already know about,” she said. “It’s not an echo chamber.” If the lesson had moved forward, students would have had the opportunity to research the topic on their own and present their own perspective, Wood said.

But the lesson plan she had for the class last spring was disrupted when complaints from students sent to the school board all but shut down the course.

“I actually felt ashamed to be Caucasian,” one student wrote in an email to a school board member, arguing that Wood’s lesson “portrayed an inaccurate description of life from past centuries that she is trying to resurface.”

“I don’t feel as though it is right because these videos showed antiquated history,” the student wrote. “I understand in AP Lang, we are learning to develop an argument and have evidence to support it, yet this topic is too heavy to discuss.”

School administrators instructed Wood to stop teaching the book out of concerns it violated a state proviso that prohibited the teaching of ideas or concepts critics have tied to critical race theory, an academic framework for studying how the development of laws and public policy contribute to racial inequity in high-level university courses. But in recent years, critical race theory has become shorthand for almost any discussion of race or racism in public schools. State lawmakers last year prohibited the discussion of classroom topics that could cause children to feel “discomfort, guilt, (or) anguish” because of their race.

Students who had been assigned the book had their copies taken away without explanation. “I couldn’t say anything,” Wood said. “I couldn’t speak to them about it.” The free-flowing discussion and debate she had nurtured in class was also shut down, replaced with quiet, rote, test-focused learning that both Wood and her students found “boring,” she said. “They would ask, ‘can we please have a debate?’ and I just said, ‘no.’”

Only after the school year, when the controversy spilled outside of Chapin High’s administrative offices, did Wood think, “Maybe in retrospect, they look back and say, ‘Oh,’” she said. “Maybe experiencing the censorship of a Black perspective gave a lesson on systemic racism.”

The experience changed the way Wood teaches her class this year. Wood is more reserved in expressing herself in classroom discussions, and in engaging with the perspectives her students bring to the class. Now when students ask questions, “I’ll say, ‘what do you think?’” she said. “That doesn’t really develop conversation or debate skills... That requires knowing how to lead conversations, which students don’t really know how to do.”

She worries the student-teacher relationship has been disrupted. “I don’t want to be taken the wrong way or misconstrued,” after the complaints about her “presented that I was trying to subtly indoctrinate them. I don’t know how they got that. I’ve always tried to make my students feel comfortable, feel engaged, to see the value in the class.”

When the time came last summer to sign up for another year of teaching, she thought about leaving. “I thought long and hard about it,” she said. All of the attention compounded what has become the usual amount of stress from teaching over recent years.

“The stress that’s associated with it, it manifests physically. I’m not certain how sustainable it is. The idea of leaving has crossed my mind on a number of occasions. I don’t know what I would do. But I just don’t know if it’s a healthy environment to live inside.”

But she still believes she can contribute to her students’ education, giving them a wider perspective of the world outside Chapin. Plus, the tone of a lot of the public criticism of her over the lesson led her to think “their intention was to push me out,” she said. “That was the goal.”

Wood is unsure why her lesson plan stirred up so much dissension. She said she taught the book in the same class previously without any controversy. Wood thinks she made herself a target “because I’m bold with my personal beliefs, which don’t necessarily align with the folks around me,” she said. She was also active last year in the school board campaign of her father, former Chapin High School principal Mike Satterfield, who won election by just 16 votes in a contentious Lexington-Richland 5 school board race, which she thinks might have also created some enemies.

She’s also somewhat skeptical if her students were actually the ones behind the emailed complaints that led to the lesson’s premature end. “I read my students’ writing when they wrote essays, and I didn’t see their voice in those emails,” she said.

Wood said the atmosphere around education has become more contentious since the COVID-19 pandemic, when many school board meetings descended into angry shouting matches over school shutdowns and COVID safety measures. As schools returned to normal from the pandemic, the same energy carried over to other controversies about what was happening in the classroom.

“I saw a shift at the local board meetings,” Wood said. “People went from being angry about social distancing and hybrid classrooms, and then they started complaining about books... and the voice certain people had developed from COVID was emboldened to come after books and literature. The divide between education and parents because of COVID was heightened and carried over to literature. You’d start hearing people complain about certain topics, and most of the books I heard lambasted had to do with people of color, the LGBTQ population, and it’s just grown from there.”

Even as the experience has disrupted Wood’s educational work, it has garnered wider attention outside of school. Last week, Wood appeared on a panel for the Center for Journalism and Democracy at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where she shared her experiences in the classroom and the challenges teachers face. The panel was called “Not a Culture War,” meant to critique the usual media framing of schoolhouse disputes.

“The idea is that the media often presents attacks on education as a culture war, as if there are two even sides,” she said. “And there are attacks on education, but teachers aren’t attacking anybody. We’re not dismissing other people or other perspectives. Our goal is to teach, which is the antithesis of fighting. It’s about empathy for other people’s perspectives and finding connections with other people.”

She also met the book’s author after the controversy was reported in The State. Coates reached out to Wood and visited her over the summer, even attending a Lexington-Richland 5 school board meeting where Wood’s lesson plan was discussed.

“I was stunned that he reached out, but he’s a normal person, he cares, and it’s good to know that people you admire share your integrity,” Wood said. “He listened a lot. He was here to listen, here to understand... I felt really isolated when this first happened, but then when I speak to people from other places, it’s good to know that people are paying attention.”

Now, the state Board of Education is considering a proposal by S.C. Education Superintendent Ellen Weaver to have all classroom materials approved by the Department of Education, whose decisions would then be binding on all school districts in the state. Wood fears that will only have a more chilling effect on classroom instruction.

“English teachers don’t rely solely on textbooks, on novels and articles, and if you limit it to what the state selects, it’s just state-sanctioned indoctrination,” Wood said. “How all-encompassing is the selection committee going to be? Is it going to include people from all backgrounds, belief systems, and experiences, or is it limited to a singular one?

“Schools are supposed to be representative of all students, and if gay students, Black students, students of color are told they’re not welcome, or their experiences are not appropriate, there are long-term implications for students. There are mental health implications, implications for socialization. There are marginalized students who need to know they have a seat at the table.”

She still believes that the lesson she had planned last spring is one that would benefit her students — and is fearful of what efforts to shut down those kinds of conversations will mean for students and for society as a whole.

“It’s harmful not just to a teacher,” she said. “It hurts students. It hurts democracy. To prevent civil discourse from taking place, it limits students’ ability to be comfortable outside their bubble. If you go to college without understanding systemic racism, you’ll have a hard time engaging with other perspectives, or perspectives in general.”

Many teachers may not be willing to speak out in such an environment, but Wood says it’s important for teachers to be advocates for themselves and the good of the children in their care.

“It’s important teachers learn their worth, and they aren’t afraid to use their voices, not just for them but for their students, for democracy as a whole,” she said. “You might say you don’t want to lose your job. There are other jobs. I don’t get paid enough not be outspoken and suffer the indignities that I suffered last year.”