'A scary place to be': Arizona State Hospital has safety, staffing concerns, critics say

Darren Beach has been living in a downtown Phoenix jail cell since Dec. 15 although his only crime, his family says, is that he has a serious mental illness and the state hospital that was supposed to take care of him didn't do its job.

Beach, 31, is accused of physically assaulting a female staff member while he was a patient at the Arizona State Hospital.

The 390-bed facility is considered the highest and most restrictive level of mental health care in the state, and no one is there voluntarily. The hospital operates on a "recovery-based" philosophy. The aim is for patients to get stabilized and eventually return to living in the community.

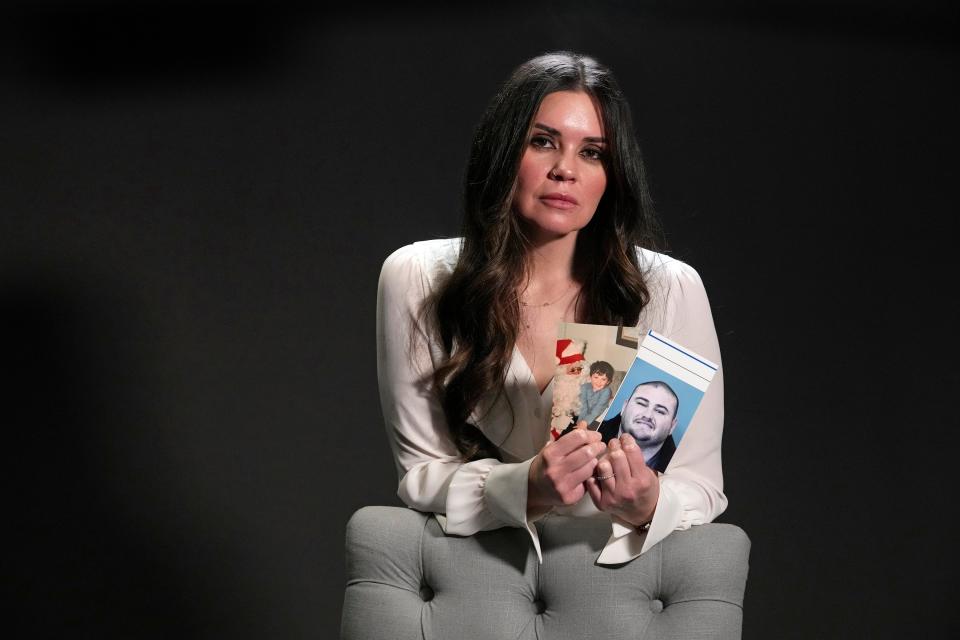

Sommer Walter, Beach's older sister who also is his legal guardian, says the assault remains an accusation and she doesn't know whether it's true.

But if her brother did get aggressive or violent, it is without question the hospital's fault for not giving him the treatment he needed, she told The Arizona Republic in an interview.

The hospital mismanaged her brother's medications, has been chronically understaffed and does not properly train its employees, and is not responsive to grievances from families, Walter said.

Walter is not alone in her complaints. She is among a group of critics who have been calling for independent oversight of the state hospital, which sits on 93 acres at 24th and Van Buren streets in Phoenix. It dates back to Arizona's territorial days in 1887, when the facility was known as the Insane Asylum of Arizona.

The state hospital has been under the state health department's jurisdiction since 1974, but critics say conditions, staffing levels and transparency have more recently become a problem, though not everyone agrees.

Some critics such as Walter are discouraged that for the past two years, state Sen. David Gowan, R-Sierra Vista, introduced legislation to mandate outside oversight of the state hospital, but both times his efforts failed.

Gowan's most recent effort evaporated June 12 when the original bill he introduced was abruptly gutted by an amendment introduced by Rep. Steve Montenegro, R-Litchfield Park. The revised bill has nothing remaining that pertains to the Arizona State Hospital.

While it houses a small number of people compared with the estimated 383,000 Arizonans who have a serious mental illness, the Arizona State Hospital is an important part of the mental health care system.

The hospital serves as a last resort for Arizonans with severe mental health problems who are under a civil court order to receive treatment and have exhausted all other options for care, or who are hospitalized because of involvement in the criminal justice system.

Beach was first admitted to the hospital in March 2021 on a civil court order.

Critics say instances of patients assaulting staff are evidence of a bigger problem in which people are being warehoused and not treated. In one instance last year, a patient was arrested after injuring a female staff member so severely that she was hospitalized and has permanent damage to one of her hands, according to the woman's lawyer.

In a separate case, a lawsuit filed against the state last year claims that one former Arizona State Hospital patient with severe mental illness named Isaac Contreras spent 665 days in a "tiny concrete seclusion room" at the state hospital, which his lawyers said was both against the law and "cruel punishment."

The case was filed in Maricopa County Superior Court. It has since been moved to federal court and is still in process. State officials in court filings have denied that Contreras was placed in a seclusion room but say he was put in "administrative separation" because he was violent, physically aggressive, a danger to others and destroyed property.

Contreras is no longer at the state hospital. He is now living with family and doing well, according to Joshua Mozell, who is one of the lawyers who filed the case.

"He is not the dangerous person they made him out to be," Mozell said. "This guy is perfectly able to operate in society, to hold down a job and to be in the community and not a treatment center. But the state hospital had to lock him down 24 hours a day. It's absurd. If that had been brought to a truly independent oversight committee, they would have ended that immediately."

Arizona State Hospital had 100 job openings as of May 31

The 116-bed civil side of the hospital includes a "therapy mall" meant to simulate the outside world. It has a working bank, library, clothing store, fitness center, post office and cafe. The programming includes arts and crafts, a book club, tai chi, gardening and karaoke, The Republic learned on a tour of the facility in early February.

Patients walked through the mall area and gathered in groups at outdoor tables. The Republic was instructed not to take any photos, recordings or directly quote anyone leading the tour.

Between the civil and forensic units and the Arizona Community Protection and Treatment Center, the average daily census at the state hospital was 316 last fiscal year, and a vast majority of the patients are male, according to state records. The 2023 fiscal year appropriation to fund all three facilities is $88 million.

As of May 31, the facility had 100 open full-time positions, hospital CEO Michael Sheldon told The Republic, including for 48 behavioral health technicians and 32 registered nurses.

The state hospital is recruiting to fill those jobs. In the meantime, the work is being performed by temporary staff with the same qualifications as full-time employees, Sheldon wrote in an email. The hospital is permitted to hire up to 729 full-time employees and as of May 31 it had 629 full-time employees, 14 part-time employees and approximately 200 contractors, he said.

"We strive to make positive improvements after any incident is reported and addressed," Sheldon wrote in response to questions about patient and staff safety. "ASH deals with the same issues facing many health care facilities in our state and nationwide and our first priority is patient safety and treatment."

The Arizona Department of Health Services as of June 20 had not responded to a Feb. 9 records request seeking a list of any deaths that happened at the hospital since Jan. 1, 2015, and a copy of all the incident reports on them. The Republic also asked for all incident reports involving assaults and injuries to staff or patients since 2015. The state has not provided those, either.

Among the known incidents at the hospital is one on Oct. 31, when there was a report of patients in the state hospital's forensic unit gaining access to a nursing station that was supposed to be secured. Two patients were arrested and three staff members were injured. A state incident report says a patient obtained a 5-pound metal pill crusher that has angled edges and began "slamming it against the plexiglass of the nursing station."

Another patient broke a vital signs machine and "took possession of a piece of plastic broken off from the machine." Because of "the rapid escalation of the situation and the presence of makeshift weapons," the incident report says Sheldon authorized a staff member to call 911.

Court documents say one patient threatened a behavioral health technician's life and punched him four times, leaving him with a shoulder injury and a concussion.

The person from the hospital who called 911 described the Oct. 31 incident as "patients in one of our units holding nurses hostage" and that some of the patients had weapons.

While state health department officials maintained the incident was "extremely rare" and disputed reports that it was a hostage situation, critics say the scenario was yet another example of how staff members don't have the proper tools to manage patients, and how patients are acting out because they are not getting the treatment they need.

Other instances of violence have been reported.

In addition to a combined 116 civil and 143 forensic state hospital beds, the Arizona State Hospital campus includes a separately licensed 131-bed Arizona Community Protection and Treatment Center for patients who have committed sexually violent offenses and are deemed unsafe to return to the community.

The Arizona State Hospital is responsible for oversight and management of the center, where in 2019 a 58-year-old resident was accused of killing an 83-year-old fellow resident, reportedly because the older man's radio was too loud.

Psychotic disorders are a common diagnosis among patients

Darren Beach was not a patient in the so-called "forensic" side of the hospital for those with criminal justice system involvement ― people who either have been found "guilty except insane" in committing serious violent offenses or who are hospitalized in an effort to restore competency to stand trial. He was not in the sex offender facility.

Rather, Beach was hospitalized via a civil court order because his mental illness is so serious and disabling that he needed the state's highest level of long-term psychiatric care, his attorney Holly Gieszl said.

"The civil court ordered him to the state hospital for treatment, and that is where he needs to be. Unfortunately, the treatment at ASH was inadequate. The conditions at ASH are horrendous at times, and Darren failed to get better there," Gieszl said in a recent interview as she stood outside Maricopa County's Fourth Avenue Jail, where Beach is housed.

"He deteriorated in what is supposed to be the ultimate level of care in the state of Arizona. ... Jail is not the best place. Never. But, ironically in this case, in some ways he's gotten better medical care here than he did in the hospital, which is why we need to fix the state hospital."

By far the most common primary diagnosis of patients in both the civil and forensic sides of the hospital is "schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders," according to a state hospital annual report for the 2022 fiscal year. Other primary diagnoses include bipolar and related disorders; personality disorders; and neurocognitive disorders, the report says.

Beach has schizoaffective disorder, is prone to delusions without medication and also has a diagnosis of autism, his sister said.

Like many other patients at the state hospital, Beach has had a difficult life. His mother died when Beach was 9, and his sister says they grew up in an abusive household, where he did not get help for his autism or his emerging mental health problems.

After he turned 18, her brother spent about 10 years living on the streets of Phoenix, she said. In 2017, he was arrested and pleaded guilty to setting fire to the one.n.ten youth center in Phoenix because of his untreated mental illness, his sister said. He was put on probation and later released.

Walter says her brother resists treatment for his mental illness, and his delusions can make him violent and destructive. But when he is getting the right care, including medication, she sees the loving brother she remembers from growing up ― the sweet-natured boy who loved action movies, Pokémon and being in the outdoors.

Beach has told his sister numerous times that his day-to-day life and the care he's getting in the Maricopa County jail is better than what he experienced during the year and nine months he spent in the Arizona State Hospital before to his Dec. 15 arrest, Walter said.

She emphasized that her brother's life is not exactly great in jail. He's locked down nearly all day, she said, but she fears that if he goes back to the Arizona State Hospital, he will just end up getting arrested again and risk a protracted amount of time in the criminal justice system.

"The behavioral health system has failed and is passing the buck onto the criminal justice system, and that's not fair," Walter said.

'We continue to ignore the most vulnerable seriously mentally ill'

Mental health advocates who believe the Arizona State Hospital needs more accountability now fear that the lack of independent oversight will allow the hospital to continue operating without adequate transparency.

"It's infuriating that we continue to ignore the most vulnerable seriously mentally ill people in our state. It's almost like they are expendable," said Deborah Geesling, a longtime Arizona mental health advocate who has a son with a serious mental illness, in reaction to the gutting of Gowan's bill. "The state hospital has just been neglected. It's like every new administration just kicks it down the road and doesn't want to address it."

Gowan has a close childhood friend with schizophrenia who inspired his interest in mental health. He told the House Health and Human Services Committee on March 13 that based on that interest, he began looking at the state hospital in 2009 during his first term in the Arizona Legislature as a member of the House.

Over time, Gowan told the committee, he noticed that when he asked about specific situations at the state hospital, he wasn't getting the information he had requested. His conclusion was that giving the Arizona Department of Health Services the authority to watchdog the Arizona State Hospital was not allowing for enough scrutiny, creating a situation akin to the fox watching the henhouse, he said.

His proposed legislation called for two key changes. First, an independent state hospital governing board would take effect Jan. 1, 2025. Oversight of the state hospital would shift from the health department to a five-member board appointed by the governor. Board members would need to have experience in hospital and health care administration. Gowan's bill called for transferring powers, duties and responsibilities relating to the state hospital from the health department to the board.

While Sheldon points out that the hospital already has a governing board and others note there's an Independent Oversight Committee, backers of Gowan's bill have said those entities are not effective enough as watchdogs of the state hospital.

The Independent Oversight Committee's role includes making recommendations to the health department director but not overriding the director. The existing governing board is technically a governing body that is appointed by the health department director and also chaired by the health department director or that person's designee.

The second change Gowan's legislation would have made is to remove caps on the number of civil beds allowed by Maricopa County, which was imposed as a resolution to a landmark class action lawsuit over mental health care in Arizona. Maricopa County's cap of 55 beds on the civil side of the Arizona State Hospital is not enough for the number of people who need them, Gowan and other critics have said.

Sheldon told The Republic that patients frequently wait for months to be discharged from the state hospital because Arizona lacks sufficient step-down facilities to reintegrate patients into the community. The situation would be exacerbated by removing the county-specific bed cap, he said.

Montenegro's amendment stripped the bill of Gowan's two key provisions. It now has a new focus: In counties of fewer than 500,000 people, it relaxes requirements that two physicians independently evaluate patients for court-ordered mental health treatment. In those rural counties, the amendment allows affidavits from one physician plus either one physician assistant who is experienced in psychiatric matters or a psychiatric and mental health nurse practitioner.

The amendment is "totally unrelated to the original bill" and does nothing to reform the situation at the Arizona State Hospital, even though it's still got "State Hospital" in its title, said Will Humble, a former state health director who is executive director of the Arizona Public Health Association.

"Looks like the fox will keep watching the henhouse," Humble said after Montenegro's amendment passed. "It is just so disappointing to see good policy go up in a puff of smoke like this. ... I hope we can trust the fox again, for the patients' and families' sake."

Gov. Katie Hobbs signed the amended bill into law on June 20.

Governor was concerned Gowan's bill was an unfunded mandate

The sudden gutting by Montenegro's amendment was a surprise to critics of the hospital because Gowan's bill had appeared to be heading for success this session. The Senate showed wide bipartisan support in a 27-2 vote of approval, and the House Health and Human Services Committee gave it a unanimous thumbs-up.

In an email, Montenegro wrote that he sponsored the amendment at Gowan's request "to reflect what was negotiated by the Senate with Governor Hobbs’ office to prevent a veto." Gowan did not respond to several messages from The Arizona Republic after the Arizona State Hospital portions of his bill were removed.

As introduced, Gowan's bill would have been an unfunded mandate that would increase costs "while not achieving Governor Hobbs’ goals of ensuring health equity for Arizona’s most vulnerable populations," Hobbs' spokesperson Christian Slater wrote in an email.

A Joint Legislative Budget Committee analysis says Gowan's original bill calling for an end to the county-specific bed cap would increase general fund costs by a one-time payment of $2.5 million and $30.3 million ongoing per year.

Hobbs has provided $3.5 million in new funding to increase security at the state hospital and remains "dedicated to ensuring ASH patients and providers are in a safe care environment," Slater said.

"As a former social worker, the governor is committed to finding a better venue to address these problems at ASH," Slater wrote. "Moving forward, we will continue working with legislative partners and stakeholders to ensure a safe working environment and better patient care."

State Rep. Jennifer Longdon, D-Phoenix, voted in favor of Montenegro's amendment. While Longdon said she supported Gowan's "legislative intent" in the bill he wrote, she's not sure she's ready to lift the bed cap at the hospital without adding more resources.

Longdon, a longtime advocate for vulnerable Arizonans, also wants checks and balances to prevent people with intellectual and developmental disabilities from ending up in the state hospital, she said. Other groups have similar concerns, among them the Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest and the Arizona Center for Disability Law, which say removing the bed cap for Maricopa County residents leaves the door open for civil rights violations, including warehousing people with complex needs.

Community-based mental health care should be improved rather than removing the county-specific bed cap and involuntarily committing more people to the state hospital, said Asim Dietrich, supervisory attorney for investigations and monitoring at the Arizona Center for Disability Law. No one with a disability, including a disabling mental illness, should be locked up in a psychiatric facility if they can safely get mental health treatment in the community, he said.

Dietrich doesn't believe Gowan's proposal for an independent governing board would improve accountability. Rather, he said a study committee needs to determine an ideal governing structure. It's imperative that the committee include all voices with a stake in what happens at the state hospital, among them current and former patients, state hospital staff and representatives from the crisis response system, he said.

"We definitely agree there are problems at ASH. There are also problems with community-based mental health care system," Dietrich said.

Before the next legislative session starts, Longdon is hopeful that "all the right voices" involved with the issue will be able to convene to find a solution that "ensures the safety, the well-being, the dignity" of the patients, she said.

"Is ASH in its current form what we need? I don't know," Longdon said. "Some of these issues might be about resources. Some of them might be about the design of the environment. I haven't dug in on ASH like I have on some other issues, but I will."

How to get help: Serious mental illness often emerges in young adulthood

'It is a scary place to be'

Mozell, the mental health lawyer who filed the Isaac Contreras case and represents several patients at the state hospital, maintains that by scuttling Gowan's original bill, state legislative leaders are turning their backs on the declining conditions for patients in the state hospital. Nothing will improve unless the structure of governance changes, he said.

"Anybody who is in and around the state hospital knows how dysfunctional it is and that the only way we're going to change that is to get some independent oversight in there," Mozell said. "I have concerns not only for the patients but for the employees that work there. ... It needs to be reformed, and it needs to be reformed now."

Given the severe mental illnesses in the patient population at the hospital, "a certain level of violence is going to take place," Mozell said. But he maintains the level of violence that's happening is beyond what would be expected.

"It is a scary place to be, and my clients that I have there, they say it's becoming more punitive and less of a community," he said. "The fact that people who are so ill that they have to go to the state hospital, the fact that they are being put into the jail, shows the lack of compassion and care that the state hospital has for the patients."

Mozell says the state hospital is a critical component in the continuum of care for people with mental illness in Arizona.

"If you don't have somewhere people can go for six months, a year, 18 months, to get stabilized and better, those people become sicker and they never get better. They end up in jails and prisons and on the streets assaulting people, incurring incredible costs," Mozell said. "When you don't have a functioning state hospital, it creates ripples all the way down that affect the system at almost every level."

Walter doesn't want her brother to return to the Arizona State Hospital. She says he doesn't want to go back, either. She's not sure what's next.

"I don't think there's anywhere else for him to go other than being outsourced to another state," Walter said. "What alternative do we have for Darren?"

How one young woman found help: Psychosis first appeared just as her life in Arizona was taking off

Reach health care reporter Stephanie Innes at Stephanie.Innes@gannett.com or at 602-444-8369. Follow her on Twitter @stephanieinnes.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: More oversight is needed at the Arizona State Hospital, critics say