How school boards became one of democracy’s front lines

Since the pandemic, Americans are paying closer attention to school boards and their meetings than ever before, but the rubber-meets-the-road government bodies — an original colonial creation — are no strangers to controversy.

Nick Melvoin got elected to Los Angeles Unified School District Board of Education in 2017 and has not seen a break in the chaos since. He has dealt with every school board controversy in the book: natural disasters, teacher strikes, Russian cyberattacks and, of course, COVID-19.

“It’s not surprising to me that we’re having these fights in our schools. It’s unfortunate. I think it’s turned a lot of people off from getting involved in the school board because people took an unnecessary amount of heat” over the past few years, Melvoin said.

Best Black Friday Deals

School board meetings functioning as political stages is hardly a new idea, though the coronavirus pandemic gave many parents an inside glimpse they never before had into their children’s education.

“I think educational politics really shifted overall during COVID,” said Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, associate professor of history at The New School. “A lot of people, because of closures, because of Zoom schooling, really woke up and started paying attention to what was going on in their kids schools.”

“That was intensified by the fact that you could now attend school board meetings, basically from your living room. You could watch the proceedings and participate. That’s going to boost political engagement,” Petrzela added.

A long legacy of education

The world’s first school board was an American creation back in 1647 when what was then the Massachusetts Bay Colony passed a law that local towns had to maintain their schools. While school attendance wasn’t strictly mandatory, it was declared that Massachusetts towns with 50 or more people would have to teach children reading and writing.

The Virginia governor followed suit 20 years later as the colonies began prioritizing education.

School boards themselves, however, were not a universal practice as many small jurisdictions simply held town meetings where all residents voted on issues such as how the school would be funded and how much parents should have to pay to send their children.

U.S. schools in the 17th and 18th centuries were largely run by private or religious means and often had strict limits on attendance based on sex, race and income status.

When the United States declared its independence, schools were still run on a very local level with varying setups such as parents paying tuition, a whole town contributing to the cost of a school, boarding schools and charity institutions for the poor.

“By the 1820s we have a pretty recognizable modern school board. It’s an elected group. They’re observing public schools the way we think of them,” said Adam Laats, a professor of education and history at Binghamton University.

The free public school system that exists today emerged in the 1830s, called “common schools,” though public elementary schools did not become commonplace nationwide until the late 19th century with high schools only becoming popular in the 20th century.

According to the George Washington University’s School of Education and Human Development, 55 percent of children between the ages of 5 and 14 were in public schools in the 1830s, rising to 78 percent by the 1870s. Schools started opening up more for girls in the 1840s.

President Andrew Jackson first created the Department of Education in 1867, but concerns about too much federal power caused it to be demoted to the Office of Education the next year. Congress wouldn’t establish the current Department of Education until 1979.

‘All the same issues that we’re fighting about now’

As a standardized school experience became more common for students in the Unites States, the rise of issues that divided school boards also began to increase.

“It’s hard to put your finger on an exact date where the politics of schools changed, but one convenient, big event was the Scopes Trial in 1925, which is when a state, in this case Tennessee, passed a law banning the idea of evolution from their schools,” Laats said.

Since there was not one concrete federal authority with jurisdiction at the time, the issue fell into a state and regional controversy, meaning neighboring towns in the same state could come down differently on certain issues, according to Laats.

Judge John T. Raulston holds the decision in the Tennessee versus John Scopes case at a courthouse in Dayton, Tenn., July 17, 1925. Scopes, a high school biology teacher, is on trial for violating a Tennessee law that forbids the teaching of the theory of evolution in public schools because it contradicts the Bible. (AP Photo)

“Depending on where you’re from, you might have a stereotype of a school board as a kind of boring, humdrum meeting, but over the big stretch of time in the 20th century, school boards over and over were the meeting point for really intense controversies that had to do with schools having religion, race, sexuality, you know, all the same issues that we’re fighting about now,” he said.

The federal role in schools expanded significantly starting in the 1950s when more money was wanted for science education after the Soviet Union’s Sputnik launch in 1957.

The growth continued in the 1960s and 1970s amid President Johnson’s “War on Poverty” before Congress officially established the Department of Education.

As school boards dealt with hot-button issues during those times, such as the desegregation of schools with Brown v. Board of Education and the sexual revolution, they also lost some power over what they could control at their institutions due to federal laws.

“What we’re seeing today is the latest example of a series of moments in American history when great political stress and unrest where the school board has become a kind of locus of controversy,” Petrzela said.

“Another example of that is certainly in the 1960s when there was a lot of curricular change, particularly around the teaching about race, immigration, sexuality,” she added. “Then what you really saw was very similar. You saw parents petitioning school boards and school board meetings often becoming very, very heated, if not violent, as these issues were contested.”

Parental rights

Over the past few years, the country has seen the rise of the “parental rights” movement, largely driven by conservatives who were displeased with the handling of COVID-19. The fight has put school board meetings into tight — and sometimes dangerous — situations.

Melissa Woods, the president of Kingsport City Schools Board of Education in Tennessee, said her role on a school board deciding on how to implement a mask mandate was her “trial by fire.”

“I took office in July, and in August we had to make a decision about masks or no masks,” Woods said.

“There were very polarizing opinions on what worked and what didn’t work, and so it was kind of baptized by fire right there at the beginning, and we made the decision to make masks optional,” she said.

But even as issues of masks and vaccines have faded, Republican supporters of parental rights have doubled down, demanding more say in what goes on in the classroom.

One of the leaders of the movement is Moms for Liberty, which was founded in January 2021 by former school board members Tiffany Justice and Tina Descovich.

Moms for Liberty founder Tiffany Justice speaks at the Republican Party of Florida Freedom Summit on behalf of the conservative “parental rights” nonprofit on Nov. 4, 2023, in Kissimmee, Fla. (AP Photo/Phelan M. Ebenhack, File)

“It has always been parental rights,” Justice told The Hill recently. “It’s never just been the toxic critical pedagogy or the masks or the quarantining or the secrets being kept from parents. The overall arching issue is parental rights. Parents have a fundamental right to direct the upbringing of their children,” Justice said. She added that “In our government schools, parental rights are being violated every single day. No more.”

The rise and potential fall of a red wave

The push has become increasingly popular among Republicans, with lawmakers earlier this year passing a “Parental Bill of Rights” in the GOP-controlled House, although it failed to advance in the Senate. The legislation would have made what books were kept in classroom more accessible to parents and forced schools to adopt policies that students could only be on sports teams and in locker rooms that aligned with their sex at birth.

While the fight may have reached a stalemate in the divided Congress, it rages on at the state and local level.

In California, the state and school boards are battling over new policies such as informing parents if a child expresses a desire to change their gender.

And Loudoun County, Va., was flooded with political controversy after a sexual assault occurred in a school bathroom, with some blaming new transgender policies that were adopted by the district. The issue, along with fights over COVID-19 mask mandates, led to death threats and police protection for school board members.

“I had a panic attack,” Beth Barts, a school board member told The Washington Post after police left her house, “because I realized: All it would take is one person believing it was their mission to do something about us all — and in five minutes, maybe even two minutes, we could be gone.”

Since the return of in-person classes and school board meetings, some unexpected incidents — ranging from the humorous to the violent — have occurred as parents try to make their point on issues they are passionate about.

Last month, an Arizona father stripped down to a crop top and short shorts to demonstrate his objection to a proposed dress code. In California in 2021, unelected protesters tried to swear themselves in as a new board. And multiple parents have read sexual explicit material into meeting records to make a point about the books available in school libraries.

The meetings have at times turned chaotic, in some cases even leading to arrests.

People hold up signs during a rally against “critical race theory” (CRT) being taught in schools at the Loudoun County Government center in Leesburg, Virginia on June 12, 2021. (Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images)

Republicans have seen education wins at the state level with the banning of critical race theory (CRT) and robust school choice legislation in numerous states, while Moms for Liberty began seeing victories on school board seats, not just education policy.

“In 2022, we endorsed — our chapters endorsed — in over 500 races for school board. Over 275 of those people won, and of the over 500 people that ran that our chapters endorsed, 76 percent of those people had never run or served in office before. That is beautiful,” Justice said.

But this year’s elections pointed to shifting winds, as voters may be growing tired of culture war issues and headlines about book bans.

Liberal candidates flipped multiple school boards, with the union American Federation of Teachers saying its endorsed candidates won 80 percent of their races. Moms for Liberty only won 43 percent.

Looking to the future

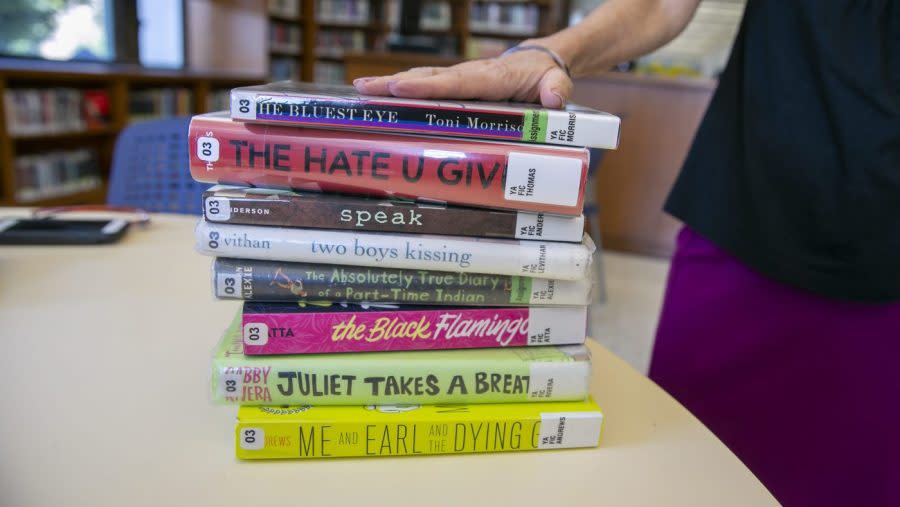

Banned books are visible at the Central Library, a branch of the Brooklyn Public Library system, in New York City on July 7, 2022. The books are banned in several public schools in the U.S., but young people can read digital versions from anywhere through the library. (AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey)

As federal, state and local control of school politics continues to evolve, it is unclear what the future will hold for how certain issues will be handled.

Jon Valant, director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institute, said how much control local school board members have can depend on the governor of their state how much those executives want to own certain issues.

The “clearest example” of this was during COVID-19 when some governors, such as Florida’s Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) wanted to be known for getting rid of mask mandates and took local control away from school boards.

“You had other states, and I think an example was Gretchen Whitmer in Michigan, where the governor was not as eager to take on all of those issues themselves and were sort of more willing to defer to districts to let them decide,” Valant said.

“I think it actually had much more to do with just like political calculation of the governors,” he added.

School boards themselves, of course, will not always be able to work around contentious topics. But then, they never have in their 375 years of existence.

In the near future, the boards appear certain to continue serving as one of the front lines of the culture wars.

Policies on how to teach LGBTQ studies and African American history are hot topics, but boards are also still debating the best ways to teach reading and math as education evolves and new methods are developed.

“There may be more focus on school boards, but school boards are pretty much on doing what they’ve always done, which is, making those critical decisions around budget, trying to hire the right superintendent in their community to make the best choices,” said Verjeana McCotter-Jacobs, executive director and CEO of the National School Boards Association. “And so school boards are making those tough — and have been making tough decisions — for a long time, whether it’s a boundary change, or if it’s around a budget. They are pretty much used to those things.”

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.