Schools are at 'a crisis point.' Can NJ weed tax, federal money save Paterson students?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

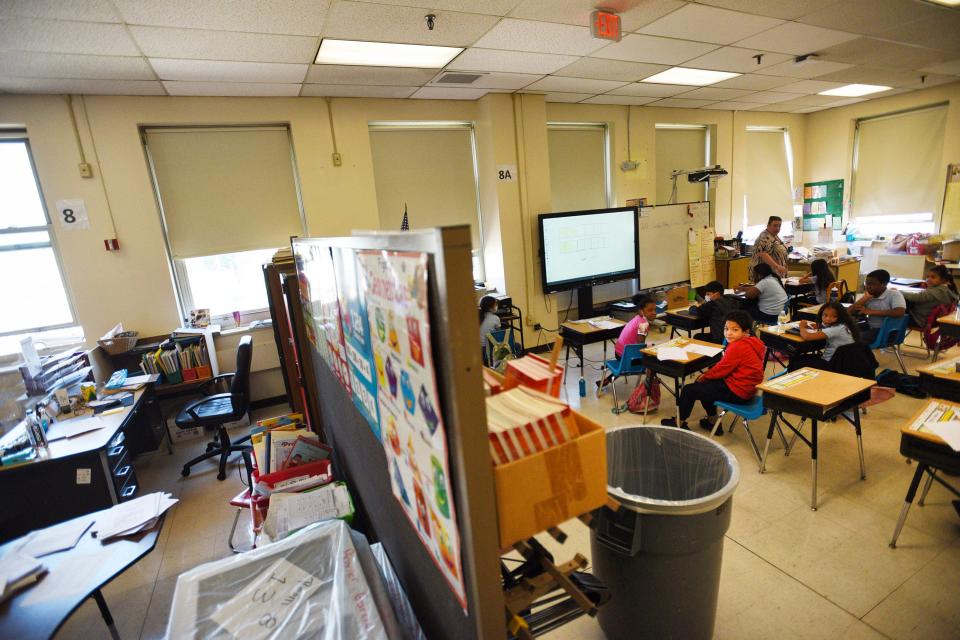

Children learn in temporary trailers because schools are short on classroom space. Teachers say they suffer stronger asthma symptoms when inside their school buildings. Waste water drips down into a teacher’s closet through a black-stained ceiling. Children hold performances, eat their lunch and take gym class in the same room — a space ill-suited for any of those roles.

Those are just a few of the myriad problems that plague Paterson students and teachers in a district where 17 active school buildings are more than a century old, and more than 1,700 students lack adequate classroom space.

In the final segment of its three-part series “Crumbling Schools, Struggling Students,” NorthJersey.com today focuses on the potential solutions that educators and experts have suggested across the country to tackle the staggering costs to renovate old school buildings and construct new ones, particularly in underserved, overburdened urban districts that lack the property tax base to pay for such projects on their own.

Although a state Supreme Court ruling ordered New Jersey to set up an agency two decades ago to pay for major school improvement projects in 28 and now 31 districts — including Paterson — that agency is running out of funds.

The governor has allocated no new money for the agency in his proposed budget.

The Legislature has not provided a permanent funding source for the agency.

And lawmakers introduced a bill to give even more schools access to the limited pie.

Advocates say the only way to seriously tackle the problem is to establish a yearly dedicated funding stream, whether through untapped state sources or from the federal government — which has not provided much school infrastructure funding in the past.

A sweltering classroom

As Shaye Brown entered Paterson’s School 18 — built in 1937 — to pick up her first grade daughter, the heat hugged her like she was in a sauna. The air felt thick.

“The room was sweltering,” Brown remembers. “My daughter was sweating. I wondered how she is supposed to learn in this environment.”

Her daughter’s teacher commiserated with her, saying the room didn’t have a working air conditioner. Brown tried to donate two extra window units she owned, but there is a process to follow through the Board of Education for donations, and equipment designed for a home doesn’t fit the large classroom windows in old school buildings.

Brown, who had worked for years in the Paterson city school district as a special education teacher, loved her daughter’s teacher and principal, but feeling the heat her daughter sweated through each day made her say, “I gotta do something better.”

The next year she transferred her daughter to the Paterson Charter School for Science and Technology.

Costliest public works project in NJ history

The series of landmark state Supreme Court rulings called Abbott v. Burke declared that it was New Jersey’s constitutional obligation to provide a “thorough and efficient” education, and that included adequate school facilities.

The state was supposed to cover the full cost of renovating and replacing old, cramped urban schools and manage the construction. It established a pioneering program, funded over time with $14.8 billion, that was the costliest public works project in New Jersey’s history and “the most extensive construction program in the U.S.”

Crumbling Schools, Struggling Students: Paterson's schools are decaying — and are hurting kids and staff. How can they be helped?

But the money raised primarily through state bonding and paid for by taxpayers is drying up, and New Jersey has not provided assurances it will continue to fund the court-mandated construction program, retired Judge Thomas Miller, in his role as special master, wrote in a March report ordered by the state Supreme Court.

Earlier this month, the state’s highest court declined to step in any further after the Education Law Center — the nonprofit law firm behind decades of school funding cases — filed a motion in court in February 2021.

The nonprofit had sought a court order to require the state construction agency, the Schools Development Authority, to secure additional money to repair old schools and build new ones. The Attorney General’s Office, arguing on behalf of the Murphy administration, said there was no need for intervention: The SDA continues to build schools, and the agency has already alerted the Legislature about its need for more money. Gov. Phil Murphy provided a one-time infusion of $1.55 billion in last year’s budget to build schools in poor, urban districts.

The state Supreme Court denied the Education Law Center’s motion without prejudice, meaning it would not order the Murphy administration or SDA to secure funds, but parties can seek court intervention for the same reason down the road, which the nonprofit has promised to do.

“The state is responsible for ensuring that school facilities in SDA districts are built and funded and resourced, and they have fallen short year after year for the last two decades,” Senate Majority Leader Teresa Ruiz, a leader on education policy in the Legislature, told NorthJersey.com. “You can see it in the buildings when it is raining outside. There is rain coming into the building because there isn’t sufficient money to replace a roof. There’s only patchwork work being done.”

It could cost $2.1 billion in today’s dollars to address 16 school projects already approved by the state, including one new school for Paterson that would cost $129 million, according to a January court filing from the SDA.

Another 50 aging schools throughout the state could cost roughly $5 billion to fix, Manny Da Silva, the CEO of the SDA, told the Legislature.

No room to shoot hoops

Children can’t shoot a basketball with much arc because it would bounce off the low ceilings of the gymnasium at Paterson’s School 19. A desk, a smart board, drawers, white board, boxes and cabinets stacked with mats are crammed into the corner, spilling over the court’s boundary lines.

So instead of basketball, gym teacher Hollie Zaccaro leads students in a game called “cleanies and messies.” She had to get creative in the cramped space.

Two teams sit cross-legged on opposite sides of the court against the walls. Dozens of multicolored cones are scattered across the hardwood floor. One team races to knock over all the cones, while the opposing team scrambles to place them upright again. Both are timed. The quickest time wins.

Immediately after Zaccaro yells “Go!” students sprint, slide, pivot, scream, groan, and hurl themselves across the floor.

After the game resets, one boy crouches, as if he’s in starting blocks, about to sprint around a track.

His head is dangerously close to the sharp corner of a cabinet against a brick wall affixed with a poster that reads in red capital letters, “DO NOT SIT UNDER THE BOX.”

“There’s no padding on the walls, and it’s freaking me out right now,” said Neil Mapp, Paterson’s chief officer of facilities and custodial services, during an earlier tour of the school.

No steady funding source

Advocates and the head of the SDA are pushing for a dedicated funding source in the state budget to cover debt service on SDA bonds, a solution other agencies such as NJ Transit have also been fighting for.

“Without a long-term financing mechanism, the SDA will be compelled to seek year-to-year funding through the annual budget process,” a strategy that creates “uncertainty that was not present when the obligation was funded through long-term bond financing,” Miller, the special master, wrote in his report.

The uncertainty about future funding makes it difficult to build schools at a steady pace, Da Silva told NorthJersey.com.

“It's easier for me to go at a steady flow than it is to speed up, slow down, speed up, slow down,” Da Silva said. “The administration was having discussions with Treasury on developing a funding stream or funding source. I don’t know that the solution has been developed yet.”

Other states have experimented with dedicated streams to fund school projects, but many aren’t available to New Jersey, and come with their own complications.

Wyoming for years used federal coal lease bonus revenues.

Most of Ohio’s school construction was funded through bonds backed by the general fund, but it also added $4.1 billion from Ohio’s share of the national tobacco settlement, and another $250 million from license fees paid by seven racetracks for video lottery terminals.

Georgia offers a 1% sales tax increase that lasts up to five years if voters approve, though regressive sales taxes hit low-income taxpayers harder.

Cannabis tax for school facilities?

New Jersey has some distinctive sources of funding that could potentially be earmarked for school projects. “We do have this new economic frontier in legalized cannabis … Is that generating enough?” said Ruiz, the Senate majority leader. “Should we consider earmarking that funding for facilities?

“There has to be a long-term discussion about some type of recurring revenue, not that cannabis taxes will be the sole funder, but maybe coupled with some creative financing, some public-private partnerships, and some bonding,” Ruiz said. “Perhaps the answer falls somewhere in that space.”

New Jersey collected more than $7.7 million in taxes on cannabis purchases from July through September 2022, according to the Treasury Department, mostly through the state’s 6.625% sales tax.

An additional $225,000 was raised in that three-month period through the Social Equity Excise Fee, an extra cannabis tax whose revenue is required to be spent in communities most affected by the War on Drugs. Nearly two dozen SDA school districts are in these eligible communities. The social equity fee could be increased by the Cannabis Regulatory Commission, with caps depending on the average price of cannabis.

Yet if New Jersey collected $900,000 a year from the social equity tax, and allocated it all toward SDA school construction debt, it would still be a drop in the bucket. The state spends $1 billion a year paying back the school construction debt issued during the 2000s.

Fast track, slow track, no track

The SDA’s success is dependent on the whims of whoever happens to hold power in Trenton, said David Sciarra, who was head of the Education Law Center for close to 30 years.

“We lurch from administration to administration,” Sciarra said. “If we get another administration when Murphy leaves that is not supportive of this program … you’re gonna have another problem. That’s a failure of the Legislature, because it could put in place mechanisms that would ensure continuous funding on a longer-term basis.”

After slowly building a massive program from scratch starting in 2000 with $8.6 billion in state-backed bonds, the administration of Gov. Jim McGreevey hit the gas: The agency spent $3 billion in its first two years and was on track to earmark all the funds by early 2006. A Star-Ledger report found that six schools built under the program cost on average 46% more than 19 schools built by local districts in the same time period.

Gov. Jon Corzine dissolved the first agency created to build school projects, the Schools Construction Corp., after a series of scathing reports showing the corporation squandered hundreds of millions of dollars and faced lax oversight. He then created the Schools Development Authority, backed by nearly $4 billion more in bonds approved by the Legislature. The new agency developed a strategic plan that considered need and resources before a project could be approved.

The Gov. Chris Christie administration halted progress on the program, and the person Murphy first picked to be the agency’s CEO, Lizette Delgado-Polanco, resigned after NorthJersey.com reported that under her watch, two dozen longtime employees were laid off and replaced by three dozen people, many with political and personal connections to Delgado-Polanco. Some were not qualified for their positions.

When Da Silva — an engineer who has worked at the agency since 2010 — took over as the agency's CEO, he had little money left to work with, until Murphy sent the agency a combined $2.25 billion in the 2021 and 2022 budgets.

New Jersey borrowed roughly $4 billion to shore up the state's finances amid the COVID pandemic — a loan it was prohibited from paying back early — but then a predicted shortfall in state revenue didn’t materialize. On top of that, the state collected billions in federal stimulus help.

With all that surplus money, the administration created a “debt defeasance fund” to cover capital projects such as train stations, bus terminals and new schools, on a “pay-as-you-go” basis instead of taking on more bonded debt.

Miller, the retired judge, pointed to the $2.97 billion that remains in New Jersey’s debt defeasance fund as a potential source to pay for school construction projects.

Ideas of what to strive for

Jodi Bland tells her fifth grade students at Paterson’s School 10 about her days as a student at Nellie K. Parker School in Hackensack. She still remembers the sweeping bank of windows in the brightly-colored cafeteria that looked out onto the playground of grass and swings.

“It was a brand-new school,” Bland said. Describing that to her students highlighted the contrast with their own school, their own cafeteria and playground. It’s “not fair. It’s not equitable,” Bland said. “They don’t know what it’s like to run in the grass. They’re playing in a parking lot. Some of them are coming from homes where they’re not allowed to play outside.”

She asks them to dream: What would equity in their school look like?

Many students haven’t been exposed to anything different, Bland says, so they think about what they see on TV. She plans field trips and mentoring programs to give students ideas of what to strive for.

They print their simple requests in careful handwriting on neon Post-It notes:

“Bigger classroom.”

“Computur lab.”

“Ballcort’s outside.”

“A safer play ground.”

“More sink’s in the girl bathroom in 2nd floor.”

No new money but a need that grows

Murphy’s latest budget proposal for the 2024 fiscal year does not include any new funds for the SDA or a dedicated funding source, though the governor did propose $75 million for repair projects. Even if that remains in the final budget, it could easily be left out of future budgets.

“The governor stands firm in his belief that every New Jersey student deserves access to a world-class education and remains committed to effectuating that mission, which includes the provision of high-quality academic facilities that best meet the needs of our students,” Murphy spokesperson Christi Peace recently told NorthJersey.com, in response to a detailed list of questions about the future of the SDA.

The need is great. SDA districts identified the need for 381 major capital projects, including 200 renovations or additions, more than 100 new schools and more than 70 major systems upgrades, according to an Education Law Center analysis of long-range facilities plans from 2016 that the 31 districts filed to the state Department of Education.

New Jersey is a microcosm of the national picture, which has a daunting estimated price tag for school construction needs — nearly $200 billion, according to a Department of Education analysis from a decade ago. A more recent report from 2021 calculated that across the country, school districts spend roughly $110 billion per year to repair and modernize facilities — but that’s $85 billion a year less than needed, according to a coalition of organizations, including the nonprofit 21st Century School Fund.

Giving charter schools a shot at SDA money?

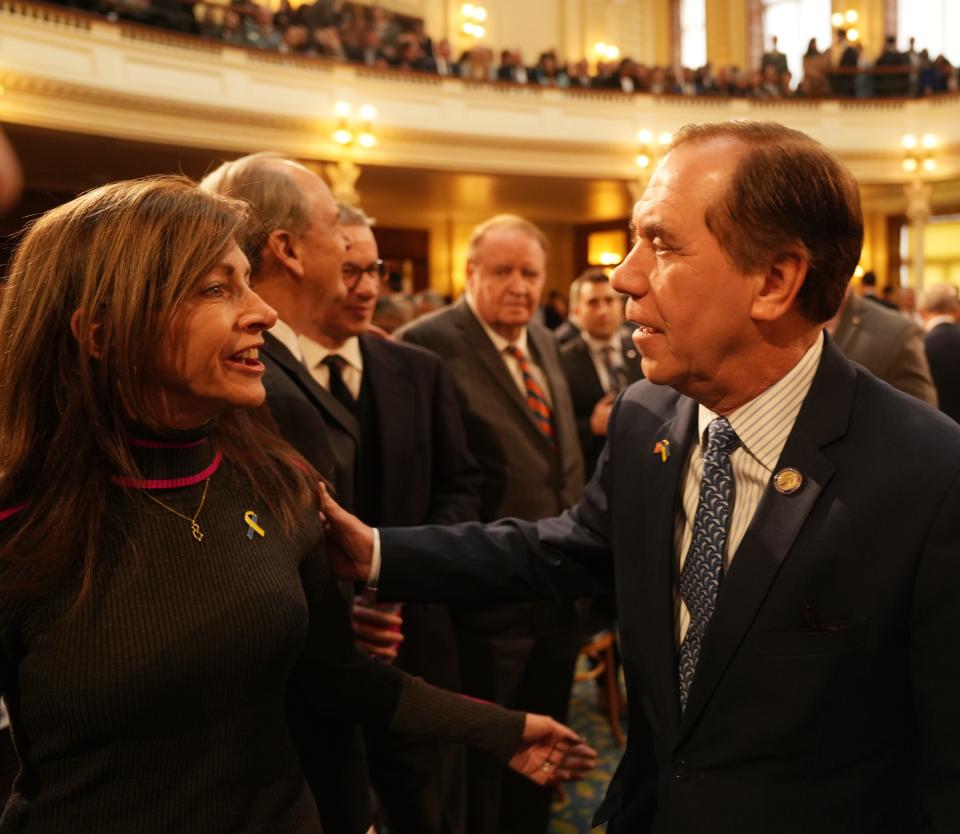

Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin has introduced an SDA overhaul bill (A4496) that would make charter and renaissance schools eligible for the first time to receive SDA facilities money, adding more schools to compete for already limited funds.

Coughlin said in a statement that the bill, which would also codify rules about standardized school designs and change how operations at the agency are funded, is intended “to maximize the efficiency of our school construction dollars.”

State Assemblyman Benjie Wimberly, whose district includes Paterson, signed on as a sponsor and supported the charter school addition because he sees charter schools as a way to reduce overcrowding in districts such as Paterson, especially since the city anticipates population growth.

The Education Law Center vigorously objects to adding charter schools. It argued that charters were not included in the court mandate that created the construction program. And including charter schools would mean using public money to build or renovate private property that would benefit the owner if the school changed location, the landlord ended the lease, or the charter school closed, the nonprofit argued.

The Education Law Center also argued that under the law, a charter school should not be approved to operate unless it can prove it has adequate facilities. Rather than diverting SDA funds to charter schools, the Legislature should make sure the Department of Education thoroughly inspects facilities before approving the charters, the Education Law Center said.

Ruiz agrees. “We have an obligation currently that we're not meeting,” she said. “To throw in other elements into the discussion, I think, just complicates the matter even further.”

Harry Lee, president and CEO of the New Jersey Public Charter Schools Association, which lobbied lawmakers in support of Coughlin’s bill, said charter schools serve one in five children in SDA districts and suffer facilities needs. “Just because you meet a minimum bare threshold does not mean [buildings] are adequate,” he said.

The bill is still “under active discussion,” said Sen. Andrew Zwicker, D-Mercer, another bill sponsor. The full legislative chambers have not voted on the bill.

'Curtains, like from the hospital'

Jufon, a fifth grader at Paterson’s Roberto Clemente elementary school, told his mother, Cameo Black, that his classroom had “curtains, like from the hospital.”

She was confused. What was her son talking about?

It wasn’t until she visited his classroom to count the students for a pizza party she was planning that she saw what he meant. His classroom didn’t have walls separating the space from two other classes. Instead, the spaces were separated by a makeshift barrier of bookcases, corkboards, hospital dividers and filing cabinets.

“When I walked in, I was like, ‘Wait a minute, am I tripping?’” Black said. She told a woman who had attended the same school decades earlier about what she saw.

“She said, ‘Yeah that’s nothing new,’” Black remembers. “So all these years it’s been going on and everybody thinks it’s normal? That’s mind-boggling that so many people think it’s fine. That’s not normal. At all.”

What does the future hold for the SDA?

The previous Senate president, Stephen Sweeney, had been pushing a bill to abolish the Schools Development Authority and give its responsibilities to the Economic Development Authority. Sweeney unexpectedly lost his 2021 election, but the Republican co-sponsors of Sweeney’s bill, Sens. Declan O’Scanlon and Kristin Corrado, reintroduced S58 in January 2022.

O’Scanlon said things have changed “significantly” and “dramatically,” given that the former SDA CEO, Delgado-Polanco, resigned and the patronage hires she brought in were ousted.

“I’m not insisting on a path of dissolving now that they’ve righted the ship,” O’Scanlon said. “The challenge now is funding.

O’Scanlon said there needs to be “executive leadership” to decide how much money the SDA actually requires. “What I fear is going to happen is we won't do a damn thing; we’ll be scrambling and in a panic, doling out billions of dollars, either bonding it or raising taxes,” O’Scanlon said. “There is no reason for desperation.”

Lawmakers said long-term solutions could include examining the operations of the SDA.

Sen. Nilsa Cruz-Perez, D-Camden, suggested tapping county improvement authorities to speed up the work of school construction and renovation. Senators on the budget committee pressed Da Silva on the urgent need to build now, while Da Silva said it takes three to five years on average from the time a school district is awarded a project until a new school opens its doors.

“Are there ways of reducing the time from shovel-in-the-ground to the opening of the door?” Ruiz asked.

She said that if a district gets SDA approval for a project, but doesn’t necessarily want the agency to oversee it, the district might be allowed to manage the project on its own.

Currently, districts are allowed to manage smaller-scale projects that deal with “emergent needs,” such as repairs to roofs, heating systems and electrical work that if left unaddressed could lead to potential health and safety issues.

Steve Morlino, a former executive director for facilities in Paterson and Newark and now a consultant for other districts, recommended that if a district has the capacity to manage a project, “the SDA should probably become a financing and inspection agency. They should be looking at, ‘OK, you need the money, we have the money, we give you the money, we oversee who you're hiring,’ but the district handles the actual project."

Paterson’s current head of facilities, Neil Mapp — who worked at the SDA and its predecessor agency for a decade — suggested an opposite approach: Expand the SDA by providing it with more staff who would be on the ground in each district so they understand what the immediate needs are at any given time.

Staff levels at the SDA are at their lowest since 2003, with 129 employees as of April 2023 — fewer than half the number in 2009.

“We'd have to increase staffing to meet those needs to be able to roll out more projects,” Da Silva told NorthJersey.com, saying the agency could use 40 additional workers. “Although understanding that on the flip side, when you dump too much into the market, you may not have the quality of a contractor to build those projects. I don't want to just take some Joe Schmo off the street that builds houses and now he's going to build a school for us. These are intricate, state-of-the art facilities.”

It’s unclear which approach — if either — the Legislature might choose. But if lawmakers don’t act soon, the decision could be made for them.

“Either we’re going to come up with [a solution] ourselves, or it’s going to come back to us dictated by the courts again,” Ruiz said.

For now, the bridge is just an idea

The state transformed a Paterson tire store into PANTHER Academy, a primarily math, science and technology high school with a domed planetarium that opened in 2004.

The “futuristic” building included 10 classrooms, two chemistry labs, a physics lab, a computer lab and a media center. But it was missing essential spaces, including an auditorium and cafeteria.

Instead, students cross Ellison Street and Memorial Drive to use facilities and take classes at Passaic County Community College, which runs a joint program with the high school.

The district explored building a bridge over the busy street so students and teachers could safely travel between the two buildings, but that never came to fruition.

The president of Paterson’s teachers’ union raised the idea again in April. A school nurse had been struck by a city-owned truck weeks earlier while crossing Ellison Street on her way to PCCC. For now, the bridge is just an idea.

How else could New Jersey tackle inequities in poor, urban districts?

The SDA’s strategic plan includes a goal to survey all 31 districts covered under the court ruling so it can understand the conditions of their 450 buildings, which would cost the agency an estimated $30 million.

Currently, districts submit requests to the SDA if a need crops up. Otherwise the agency periodically asks districts to list their needs. During the round in July 2016, 23 districts that participated logged 429 project applications. Paterson alone listed 77 projects.

The process has drawbacks, Da Silva wrote in a state Supreme Court filing. The information that districts provide the SDA is often incomplete, with the underlying problem unidentified.

Districts don’t always understand the types of projects eligible for SDA help, or the hazard may have already grown too dangerous and a project under SDA direction may not move swiftly enough, Da Silva wrote.

Surprisingly, Paterson is not included in the portion of the SDA’s strategic plan that lists 50 facilities statewide with age-related issues.

“I don't know how that didn't get flagged. It's either Paterson didn't flag it or the Department of Education didn't flag it,” Da Silva said. “There was either a disconnect or it wasn’t identified.”

Wimberly, the assemblyman representing Paterson, was surprised to learn the city wasn’t on the list. He found out only because NorthJersey.com asked him about it.

“We have to be in the top,” Wimberly said. “That’s something that the [Paterson] administration will have to answer for.”

![Assemblyman Benjie Wimberly was surprised Paterson is not included in the portion of the SDA’s strategic plan that lists 50 facilities statewide with age-related issues. “We have to be in the top,” Wimberly said. “That’s something that the [Paterson] administration will have to answer for.”](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/z7buHaaV6I7OiICp6cOqGw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0Mg--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-bergen-record/517c0f86a565cf28e847222fdd4ec403)

A comprehensive assessment could help the agency look across all 31 SDA school districts and be smarter about how to use the limited resources. For instance, if five schools have leaky roofs, a contract for one project that addresses all the schools could be more efficient than having each district contract out on its own.

For the agency to conduct a statewide assessment, Da Silva estimated, it would take four to six months to hire the firms and then a year to survey all the schools.

But it’s unclear when such an assessment would take place.

Da Silva also told lawmakers that having districts turn in long-range facilities plans every five years for the SDA to create new strategic plans can be too infrequent — facilities issues can crop up far more quickly.

Federal funding to the rescue?

States and local school districts are poorly equipped to tackle such an expansive and expensive challenge as building new schools and refurbishing old ones — it requires the strength and purse of the federal government, some advocates say. Schools make up the second-largest chunk of public infrastructure spending after highways and are important resources that benefit every community, they say.

Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., has championed the issue, introducing the Rebuild America’s Schools Act, which would invest $100 billion in need-based grants over the course of five years and $30 billion in bond authority to high-poverty schools, and require state governments to publish databases on public school conditions.

“It’s really reaching a crisis point,” Scott told NorthJersey.com. “For the average student, state and local can do a good job with funding, but there are some areas where there are chronic shortfalls. School construction — particularly in low-income areas — is one of them.”

Advocates rejoiced when President Joe Biden proposed a $100 billion infusion of federal dollars and bonds in the American Jobs Plan, a $2 trillion infrastructure plan he put forward in March 2021. But as congressional negotiations wore on, it was struck entirely from the final compromise.

That would have been an atypical investment. The federal government historically has not played a large role in funding school facilities, making up 1% of funds dedicated to school infrastructure, or $7 billion, between fiscal years 2009 and 2019. Much of that money came from FEMA in the wake of natural disasters.

NorthJersey.com contacted New Jersey’s two senators and 12 representatives to ask if they would support dedicating federal funds for school facilities projects.

Rep. Josh Gottheimer, whose North Jersey district does not contain any SDA schools, said in an interview, “I think we need to be making targeted federal investments in SDA districts and all districts in need so that we’re improving infrastructure and educators have what they need. It’s hard to concentrate on educating and teaching if you’ve got a leaky ceiling.”

Gottheimer said he fought to include money for school facilities in the federal infrastructure package he had a role in negotiating, but “we needed Democrats and Republicans, and we couldn't get there on this school piece.”

Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman, whose district contains the Plainfield and Trenton school districts, said in an email, “The federal government has a responsibility to ensure that schools have the resources they need to safely and effectively educate our children.”

Rep. Frank Pallone, who represents a handful of SDA school districts, said in an email, “All students deserve to learn in clean and safe environments, which is why Democrats delivered billions of dollars in new federal funding to support students and teachers since 2021. I’ll continue working to help make sure our schools provide an engaging and supportive environment for learning.”

Reps. Andy Kim, Donald Payne and Mikie Sherrill declined to comment, and eight New Jersey members of Congress — including Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr., who represents Paterson — did not respond.

“This is just a problem that is so expensive in scope that it goes beyond the ability of one community tax base to be able to afford to address,” said Elleka Yost, director of advocacy for the Association of School Business Officials International.

“If someone has figured it out,” Yost said, “they are sitting on the secret.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Paterson schools desperately need funding. Can NJ weed tax help?