Schools have ‘failed us.’ Some NC students say more Black history needs to be taught.

North Carolina students will almost certainly learn about Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. in school But there’s no guarantee they’ll be taught anything about the 1898 Wilmington massacre and other parts of the state’s Black history.

Some teachers and students say North Carolina’s social studies standards are written in such a way that it makes it’s easy for schools to ignore national and state Black history or to give it cursory treatment. As schools mark Black History Month, these educators and students say Black history shouldn’t be relegated to February, if at all.

“I’m a Black girl,” Victoria Smith, 18, a senior at Enloe High School in Raleigh, said in an interview. “I have to know my history. Because if they won’t teach me, who else will? Sadly, the school systems have failed us when it comes to learning about Black history.”

Smith is founder and president of the Wake County Black Student Coalition. In addition to calling for counselors to replace police officers in schools, the coalition also wants the Wake County school system to make a Black History course a requirement for students.

The issue of how to discuss the perspectives of Black people and other minority groups was part of much of the recent debate about newly adopted state social studies standards.

Supporters of the new standards want to do more to ensure that the perspectives of historically marginalized groups will be discussed in social studies classes. But critics say the new standards will be divisive and promote an overly negative view of the United States.

The state Department of Public Instruction is continuing to work on documents to help teach the new standards.

Teachers and school districts can vary widely

In the meantime, teachers will continue to use the existing social studies standards that lay out the framework for what should be taught. But state leaders say the current and new standards are not meant to be a curriculum. It’s left up to each school district how to teach them.

Unlike many other subjects, there are no state exams for social studies courses. Students specifically learn about North Carolina history in 8th grade but also as part of other social studies classes, including American history and civics.

But the standards are so broad that it’s up to each teacher to decide how much — or how little — Black history they want to share, according to Rodney D. Pierce, an 8th-grade social studies in Nash County Public Schools. Pierce helped write part of the state’s new more inclusive social studies standards.

“It depends on your teacher,” Pierce said in an interview. “Of course your teachers are going to talk about Black history in Black History Month. What are they going to do the other months of the year?”

What teachers share with students in social studies will depend on their individual perspectives of history, according to Katrina Smith, a 5th-grade social studies teacher in Nash County Public Schools.

“How I teach something is probably going to be different than how another teacher teaches it in a different school,” Smith said in an interview. “We have different interests.”

Skipping the Wilmington massacre

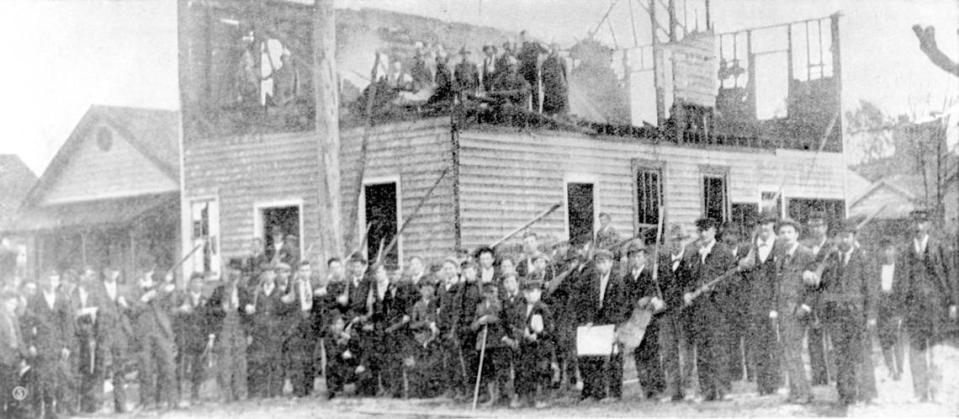

Both the state’s 8th grade and American History 2 standards list the 1898 Wilmington massacre as an example that teachers can discuss.

In 1898, white supremacists helped to violently overthrow Wilmington’s elected multiracial government. They were aided by propaganda from News & Observer publisher Josephus Daniels.

But this pivotal event in the history of North Carolina and the nation is not required to be discussed.

“Most North Carolina high school teachers have either a non-existent grasp of it or a weak grasp,” John deVille, a social studies teacher at Franklin High School in Macon County, said in an interview.

Some teachers, deVille said, also are worried about parents complaining that the coup is being taught. “There’s also a hesitation of will it make the phone ring?”

Reagan Razon, 17, a senior at Enloe High School in Raleigh, is among the students who say the coup was never mentioned in their social studies classes, even though they discussed other events from the 1890s. Razon said she learned about the coup during last year’s nationwide protests over the killing of George Floyd and other Black people by police officers.

“It’s skipped over,” Razon, an executive at large with the Wake County Black Student Coalition, said in an interview. “It’s just so weird to me. You can pick and choose which things to talk about from the same year.”

Whitewashed Black history?

Some Black students say what they learn about Black history in social studies is a whitewashed, simplistic version.

Students don’t learn how the enslaved people were fully formed individuals with very rich cultures and rich languages, according to Jordyn Shumpert, 17, a senior at Enloe High and a member of the Wake County Black Student Coalition.

“We’re just taught about slaves as if they’re cardboard cutouts to pity and then like that’s it,” Shumpert said in an interview. “We’re taught that slaves were 2D.”

Chalina Morgan-Lopez, 17, a senior at Sanderson High School in Raleigh and a member of the Wake County Black Student Coalition, said much of what she learned about Black history was from her parents and not in school.

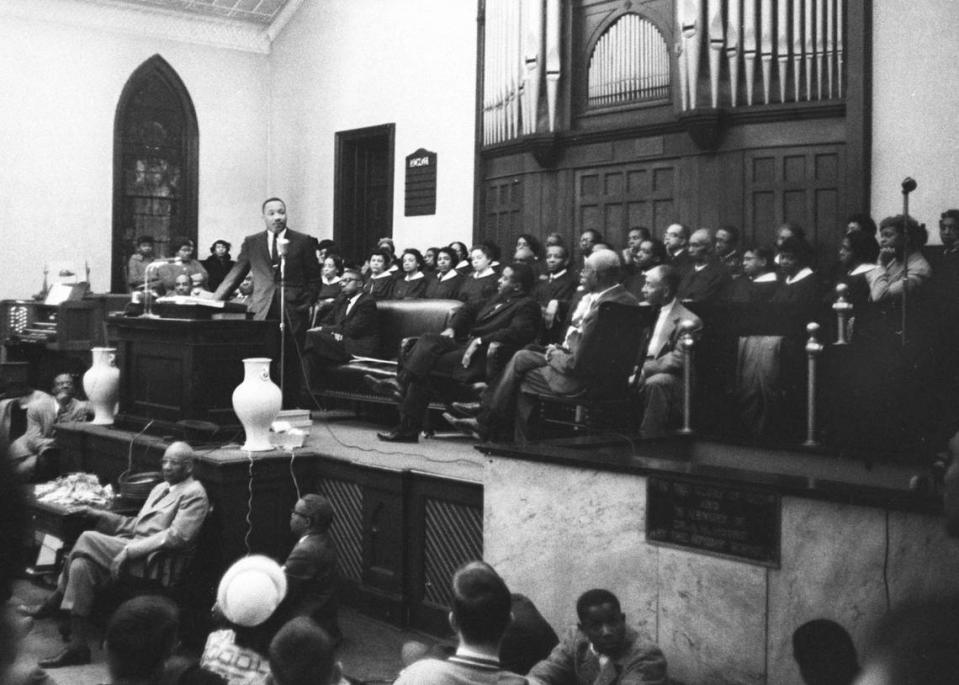

“When it comes to learning about Black history in the Wake County Public School System, we only learn about Rosa Parks and MLK and they only ever talk about Black history, I feel, during Black History Month,” Morgan-Lopez said in an interview.

It’s only due to the summer protests, Victoria Smith, said, that she learned that Black people were lynched in Moore Square in Raleigh.

KaLa Keaton, 17, a senior at Middle Creek High School in Cary, said what she mainly learned about Black history in social studies was about slavery, the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement. But Keaton said even when they discussed Martin Luther King Jr., her teachers acted as if the only speech he ever gave was his 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech.

Keaton said she didn’t start learning about things such as the Wilmington massacre, the state’s eugenics movement and lynchings until she took an African American literature class and later a “Hard History and Civic Engagement” elective class in high school. This included working on a project to bring attention to the 1918 lynching of George Taylor near Rolesville.

Keaton is among a group of students who last summer urged the State Board of Education to make the social studies standards more explicit about covering different groups. She said it will benefit all students, not just people of color.

“Being a Black student in a predominantly white school, I’ve gone through the experience of racist jokes,” Keaton sad in an interview. “But I think when you truly go more in-depth into what people of color, and especially Black Americans, had to go through ... that will challenge a lot of perspectives and beliefs that come from home. You don’t know what you don’t know.”

Black NC history examples

The social studies teachers — deVille, Pierce and Smith — say there’s so much Black history in North Carolina that their fellow educators can pull from to help make the classes more interesting to students.

For instance, Pierce had his students look through the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau field office that was set up in Rocky Mount to help Black people during Reconstruction.

Smith talks with her students about Sarah Keys Evans, the North Carolina woman whose refusal to give up her seat in 1952 led to the outlawing of segregation of Black passengers in buses traveling across state lines.

deVille helps his students confront the grim reality of racism with examples such as how a prominent Franklin doctor hung the skeleton of a lynched Black man in his office until the 1950s.

Other examples include:

▪ Julius Chambers, the attorney in the Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg case that helped expand school integration locally and across the country.

▪ Dorothy Counts, who integrated Harding High School in Charlotte in 1957.

▪ Robert F. Williams, a NAACP leader from Union County, whose writings helped inspire the Black Panther Party.

▪ The formation of Black Panther Party chapters in Raleigh and Winston-Salem.

Smith, the teacher, said that making the material relevant is particularly important now that the majority of students are people of color. She’s hoping the newly adopted standards will do a better job than what’s in place now.

“You wonder why the children aren’t interested in learning about history?” Smith said. “How would I be interested in something that doesn’t apply to me?”

Students need to learn more than just about white European western history, according to Smith, the high school student.

“We need to incorporate not just Rosa Parks, not just MLK, but true Black history that is seen,” Smith said. “There are so many Black figures that go unheard that need to be taught. It’s wrong for people to say it’s OK to skip over that.

“Because it’s not.”