Should schools fear cheating with AI? Tri-Cities teacher says it could be revolutionary

Most teachers will open a textbook or reference the curriculum when students ask a tough question.

But John Weisenfeld wants to go a little further.

The Pasco High School science teacher is quick to his keyboard — to Perplexity AI or any other artificial intelligence chatbots — to find the answer.

“It allows me to capitalize on the energy and interest of the moment and provide accurate, targeted, detailed information,” he said.

You’ve probably heard of artificial intelligence, or AI. It’s an umbrella term that’s been used for decades to describe any machine-learning technology for completing tasks.

The rise in recent months of generative AI websites that use computers to create content — such as text from ChatGPT or image generation from DeepAI — has prompted discussion far and wide about the technology’s role in many industries.

In education, many public schools and universities went on the offensive and blocked popular sites early on. The fear was that students would use text generators to fake essays or to cheat on their school work.

But now school districts from Walla Walla to New York are reversing those decisions, some claiming to embrace the potential of this “game-changing technology.”

Weisenfeld says it’s the right move.

He believes AI technology has the ability to revolutionize the way educators work and teach — in planning, grading, instruction and beyond.

It also can help students gain a deeper understanding of concepts.

“My goal is to make teachers more efficient or get more enjoyment from what they’re doing. But that also spills over to students,” Weisenfeld, who started a 400-person email group on tech tips for his district.

AI in the classroom

Weisenfeld has always been at the forefront of technological innovations.

Before he began teaching in 2011, he spent a decade as a software test engineer with Microsoft, working on Windows Live Messenger and on apps in the Office suite.

Not all teachers are as plugged into AI as he is.

About 40% of teachers surveyed in Education Week say they know enough about the technology to understand it but have never used it. Roughly 1 in 10 say they know enough to teach it or use it to some degree in their work.

Weisenfeld began implementing AI into his instruction and first began to consider the broader uses for students last year. That’s when he assigned an essay in his nanotechnology class asking students to explain why geckos can walk upside down.

He gave them the assignment and rubric, and encouraged them to use chatbots to ask questions and write detailed answers.

“It was an ‘aha moment’ because I realized we can start asking better and better questions,” he said. “This could raise the academic language and engagement in any class.”

Instead of simple responses, Weisenfeld said students dove into complex topics and detailed explanations of the gecko’s setae, spatulae and the Van der Waals forces.

After receiving their first draft, Weisenfeld fed the student essays into a chatbot for revision feedback.

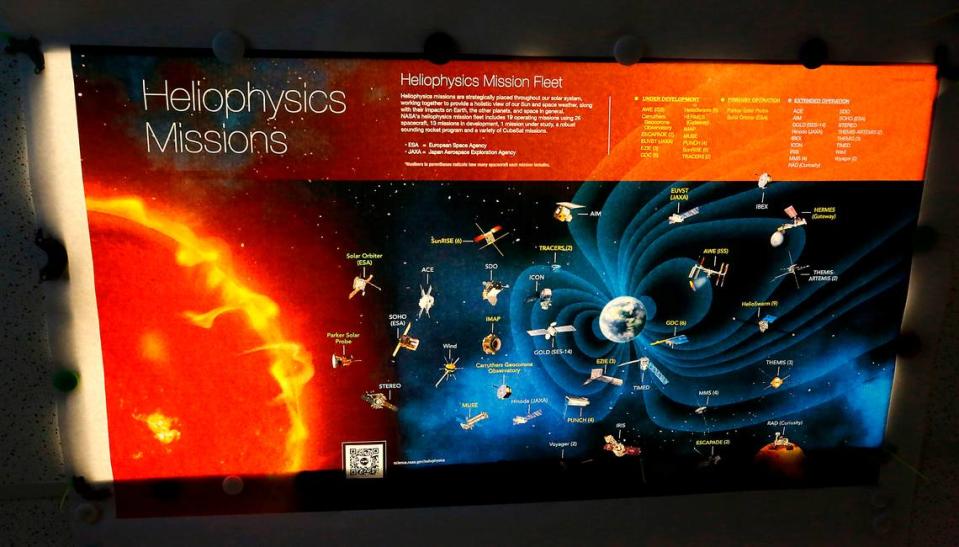

The Pasco teacher also had his astronomy students ask AI chatbots for information about interplanetary NASA missions and if they could play a part in warning the Earth about major solar storms in the future.

A poster detailing the missions hangs in his classroom.

Educating our ‘digital citizens’

Most school districts in the nation and Washington state — including Pasco, Richland and Kennewick — have not yet drafted a policy on the use of AI in classes.

Mira Gobel, Pasco’s assistant superintendent of schools and social-emotional learning, said while it’s important to use the technology to enhance education, it’s also an opportunity to teach students what it means to be a “digital citizen.”

“They’re the digital generation without the understanding of what it means to be a digital citizen... I think we also need to do our due diligence in doing that education simultaneously,” she told the Tri-City Herald.

In a statement, the Pasco School District said its next steps with AI will be informed by “rigorous research-based best practices, with careful consideration of the policy and practice implications, ensuring that our students and staff benefit from the most responsible and beneficial use of artificial intelligence in education.”

For example, AI could be beneficial in teaching English phrases and sentence structure in Pasco schools where one in three students are English language learners, said Gobel.

“I think it’s new ground for most districts,” she said.

In Richland, the school district does not currently have a policy in place on students and teachers using AI.

But, like most school districts, students there are required to cite sources and information if they pull from others’ work.

Collin Gibbs, a history teacher at Hanford High School, is using AI tools, including ChatGPT, in the planning, organization and instructional design process and is sharing his results with fellow instructors, said district public information officer Shawna Dinh.

“He views the use of AI as a thought partner and believes that both proactively supporting his colleagues and teaching students how to use AI as a tool is the best and most productive path forward,” Dinh told the Herald.

Both Richland and Kennewick school districts are currently gathering information to begin drafting policies around the use of AI in the classroom.

“We are in the process of learning and conducting research and a committee will be working to develop draft policy, with input from stakeholders, to bring to our board sometime after the first of the year,” said Robyn Chastain, Kennewick’s executive director of communications and public relations.

Do student’s cheat?

Weisenfeld compares the conversation we’re having today about AI with a similar one teachers were having decades ago with digital calculators.

Teachers are worried about cheating — and so are students.

A recent Junior Achievement-Big Village national survey showed while nearly half of students say they were likely to use AI to do their school work instead of doing it themselves, about 60% also perceive a reliance on AI as cheating.

But both Weisenfeld and Gobel see AI as more of a tool than a crutch.

“When I think about the cheating-plagiarism question, well, what if I tell students, ‘You have to use ChatGPT on this assignment?’ Well, then we turn things on its head,” Weisenfeld said.