Schools spend billions on training so every student can succeed. They don’t know if it works

Tampa, home of the nation’s seventh-largest school district, offers a glimpse into the country’s multiracial future: White students make up less than a third of students, Hispanic students another 38%, Black students 21% and Asian students 5%.

The percentages break differently when looking at academic achievement and discipline, however. Significantly larger numbers of white students enroll in calculus and advanced science classes, while Black students disproportionately experience suspension and expulsion – a consistent trend in schools across the nation.

To try to eliminate this disparity, Tampa puts a heavy emphasis on equity and racial justice when allocating the $36 million it spends each year on professional development for educators. Teachers can access online and in-person training on topics including implicit bias, culturally relevant pedagogy and connecting with English-language learners. “We really focus on building that inclusive climate and culture,” said Jamalya Jackson, executive director of professional development for the Hillsborough County School District, headquartered in Tampa.

Yet the district doesn’t measure whether the training directly changes educator beliefs, teachers’ behaviors, or student outcomes. Jackson couldn’t point to a single evaluation method that asks a question deeper than whether teachers found the material useful. Even the district’s online training – potentially more easily evaluated or tracked – offers policy makers little insight into whether the investment is successful because it doesn’t measure student outcomes.

Tampa isn’t alone. For decades, urban educators have struggled to narrow the gap between Black and white students’ performance in school, which appears as early as preschool, and to end the disproportionate punishment and suspension of Black and brown children, and those with disabilities. From Title I to No Child Left Behind to the Every Student Succeeds Act, wave after wave of federal, state and local policies have attempted to solve the disparity, without much impact. While overall suspensions have declined in the last 20 years, Black students are still disproportionately suspended and expelled compared with white students. That puts them at higher risk for arrest and incarceration, a phenomenon known as the school-to-prison pipeline. The achievement disparity is even more stark: Not only do Black 12th graders read at a lower level than their white peers; on average, they perform lower than white 8th graders, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress. The pandemic upped the ante, because learning losses overwhelmingly hit Black and Latino students.

Who's teaching the teachers? These organizations dominate equity-oriented training for big school districts

In recent years, discussion of racism in public school has become a political punching bag, with states passing laws against so-called critical race theory and school boards across the U.S. banning books with themes of race and racism. Lawmakers in Florida and Texas have passed bans on diversity offices at the higher education level, and similar legislation is pending in Ohio.

Despite all this, public schools spend more than $20 billion annually on teacher training to help the nation’s teachers, a majority of whom are white, teach across lines of racial identity. However, none of the 42 large U.S. school districts interviewed for this project measure the impact of their training against metrics or evidence generated in an objective research study. (This differs from how schools handle reading and math curriculums, which are often tested rigorously.) As a result, it’s hard to distinguish effective from useless diversity, equity and inclusion training, and that lack of clarity may prompt more criticism of equity-oriented professional development. In the current climate, effective teacher training is even more important, as many experienced teachers have retired and churn is expected to continue.

Daytona Beach schools, in Florida, for example, hired a consultant to train administrators and school counselors on equity, so those individuals could continue the work indefinitely. Every teacher in the district attended the training. “We know it is not a one-time event,” said Wafa Picciolo, coordinator of professional learning for Volusia County Schools. “To meet the needs of all our students, we need to continue with equity-oriented PD.”

School leaders aim to end bias and disparity

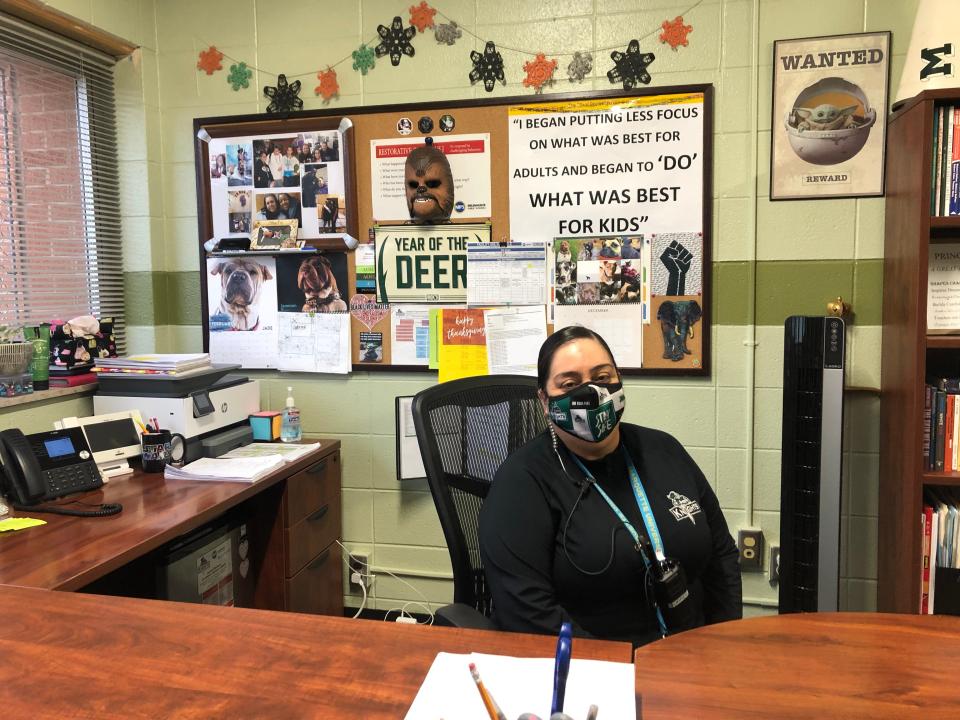

On a cold morning last winter at James Madison Academic Campus in Milwaukee, the office of then-Principal Jineen McLemore Torres was dotted with racial-justice literature and positive slogans. Her bookshelves displayed classic tomes on race including “White Fragility,” “The New Jim Crow,” “Stamped From the Beginning,” “Hood Feminism,” and “Pushout.” Her wall decor included Shar Pei photos and Star Wars memorabilia, as well as photos of students and staff. "Do, or do not, there is no try," stretched across a bulletin board.

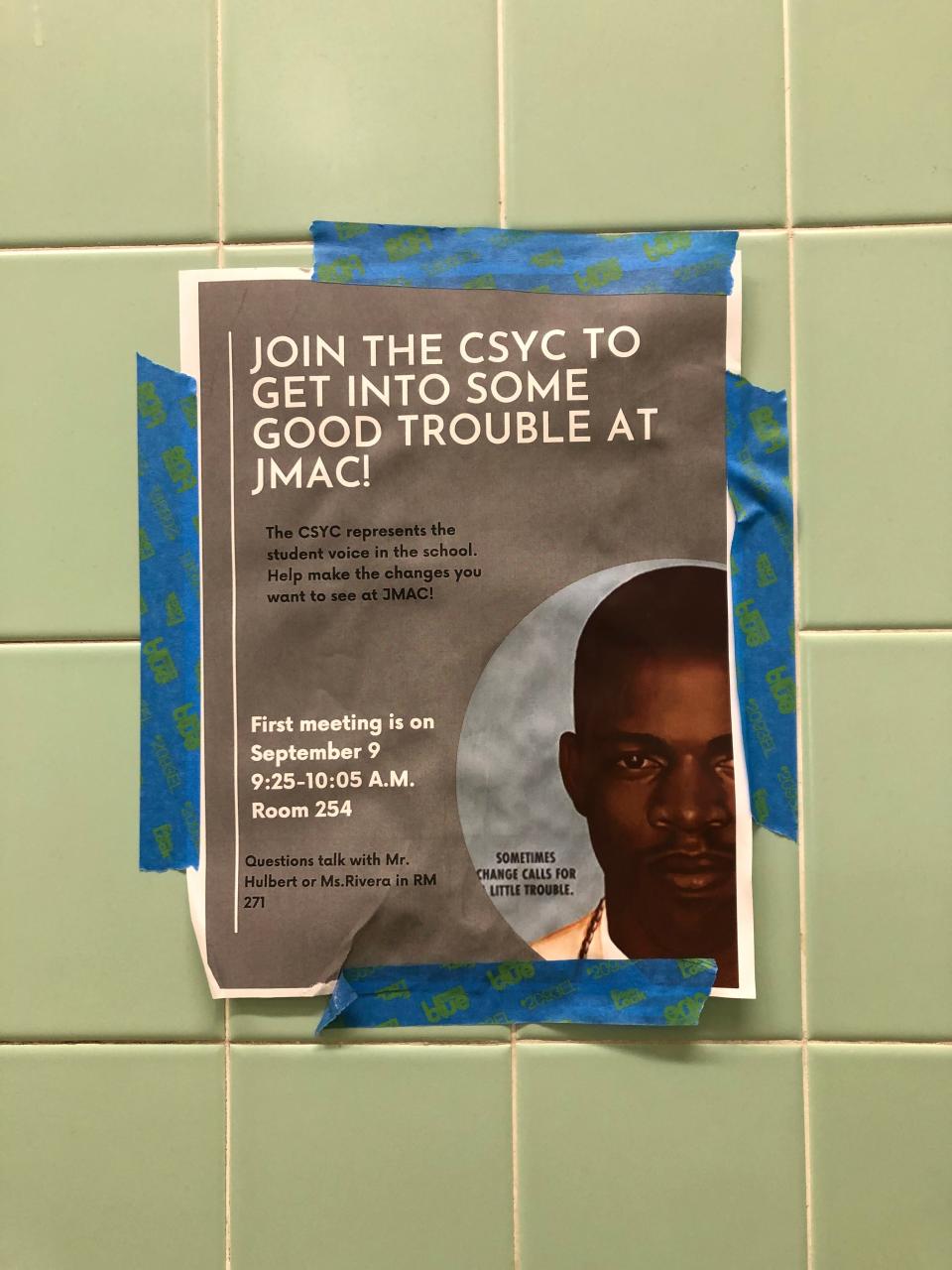

With a majority Black population, JMAC experiences the full pressure of Milwaukee’s efforts to narrow racial disparities, following an investigation by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights that the city settled in 2017 by agreeing to take specific steps to promote equity and report progress. The school district offers a monthly lunch-time youth council meeting for students to give input on academics, school climate, food choices and other topics. Educators seek to teach culturally relevant curricula, such as a lesson on the play “Fences,” by August Wilson, being taught that day in an AP literature class. Educators discuss difficult topics in book groups and staff meetings.

It’s quite a change from when Torres first arrived at JMAC as an academic coach a decade earlier, when the high school included a large Hmong population. Teachers seemed to take for granted that Hmong students were capable of high-level academic work, while discounting the abilities of Black students. “You could see the difference in how teachers treated Hmong kids and how they treated our African American students,” Torres recalled, in an interview last winter. “That hurt my heart to see. Why is this happening? It’s all the biases.”

To be sure, progress has been halting – and it can be hard to quantify change. At one point, school leaders wanted the whole staff to take the implicit bias test, which assesses your hidden stereotypes about race. But some staff members said they didn’t see a problem, since slavery had ended. Or they’d say that all lives matter. Torres realized that forcing a conversation might actually harm staff of color, because a foundation of shared understanding hadn’t been laid. “We have to get to a point where we can have the conversations. We've got to be able to say, ‘I might have treated this kid a little different because of XYZ,’” she said.

Lessons aimed for students 'to be nice:' That's controversial in Florida now under DeSantis.

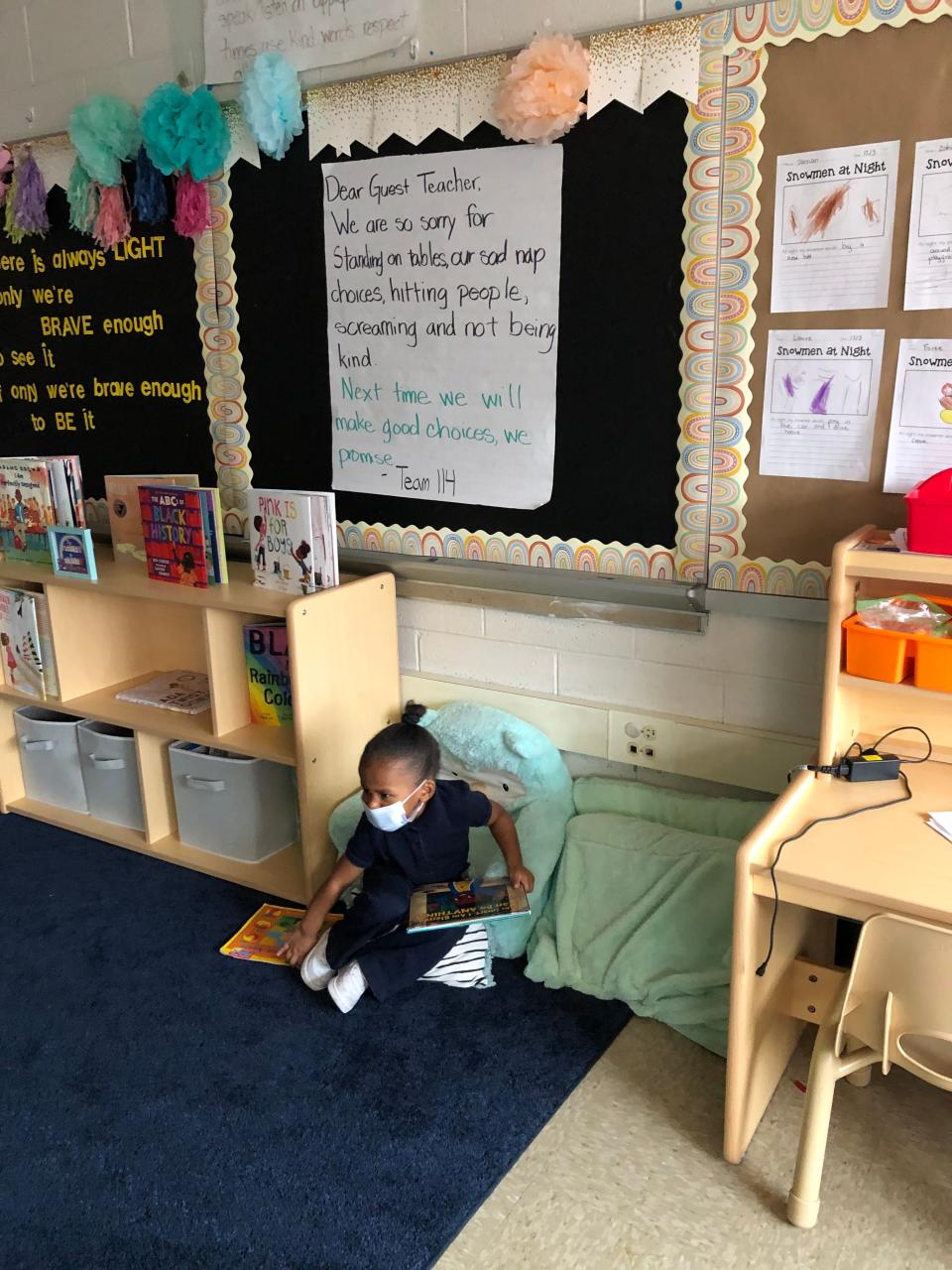

The biggest change has been prioritizing educators’ responsibility for students’ social and emotional needs, rather than drilling down on math and reading lessons. Students give input on norms and expectations at the beginning of the year. If a student cusses Torres out, she won’t leap to punishment. Instead, she’ll bide her time until they need a hall pass or a bathroom unlocked and let that request prompt a conversation about the cursing.

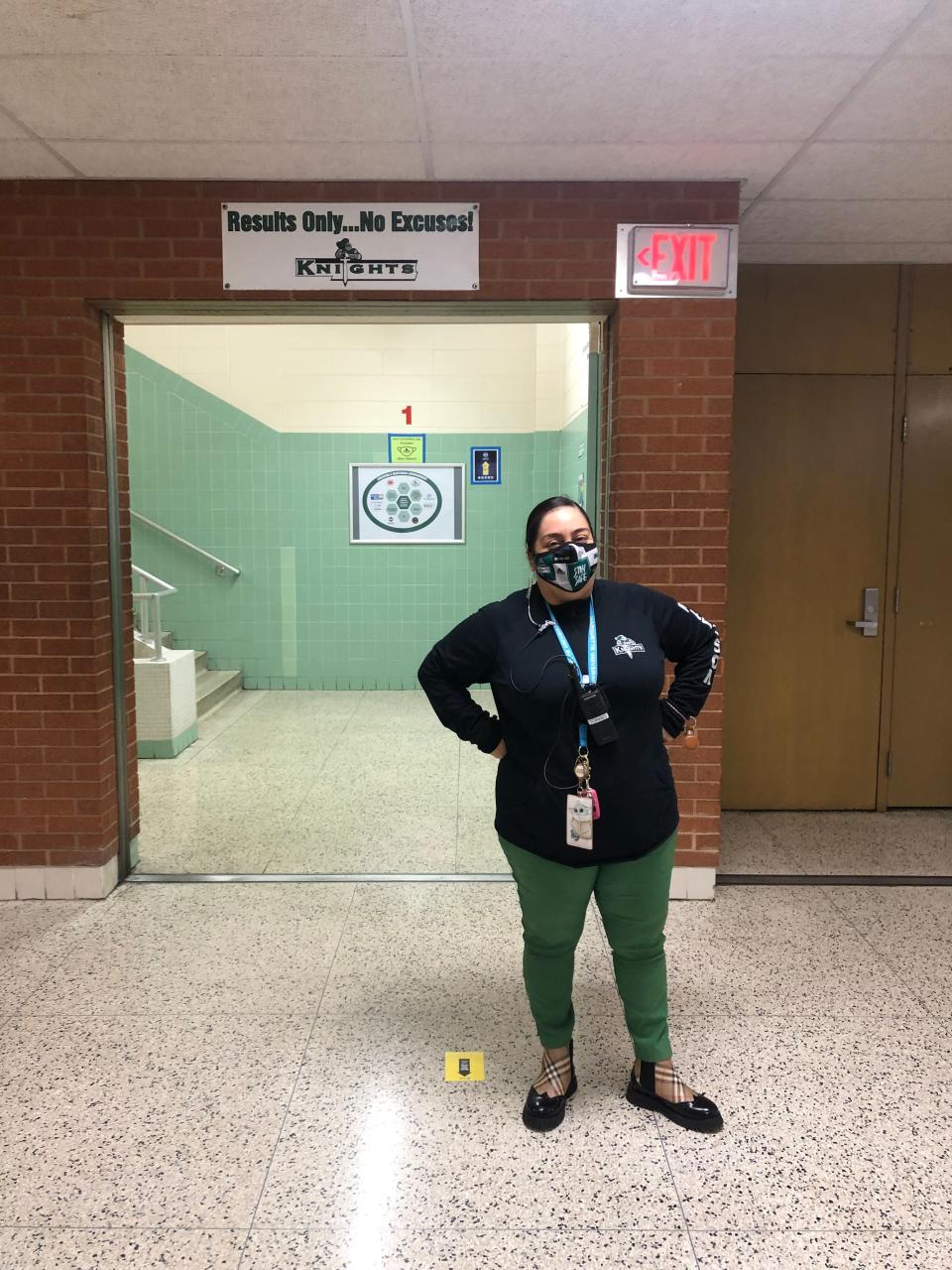

Even so, it was clear she ran a tight ship. As she walked through the hallways, she greeted students by name and asked about the class they should be in. The bell had rung a few minutes earlier, so everyone should have been in a room. Torres rounded the corner, and as soon as she came into view, a boy pushed off from the locker where he’d been leaning and headed off purposefully. Despite being just 4’9”, Torres clearly conveyed authority.

African American students in Milwaukee are suspended more often and for longer than their peers, across the school district. Under the consent decree with the Office for Civil Rights, Milwaukee reports data on student discipline, achievement, professional development, and other metrics, annually.

“Our big push is looking at the role of bias in our schools and what are the strategies to disrupt it,” said Jon Jagemann, the district’s discipline manager, who brought the Courageous Conversation organization’s one-day seminar about race and equity to the district. All administrators, on-site social workers and counselors have taken it. About 80% of classroom teachers have taken it, putting the district on track to train all staff by March.

The history of equity-oriented teacher trainings

The catchphrases used for diversity training run the gamut from implicit bias to equity mindset to courageous conversations to anti-racist competencies to decolonization. These programs arise from a long history of adult education that seeks to eliminate the persistent racial gaps in public schools. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education case and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, schools convened desegregation workshops. By the 1980s, professional development had a new focus: appreciating the diversity of people from all backgrounds.

Scholars including Gloria Ladson-Billings introduced the concept of multicultural education in the 1990s, around the same time psychologists were identifying and describing implicit bias. Bias comprises split-second judgements and decisions about another person based on stereotypes around race or other identity, without conscious thought. Through the 2000s, more schools were offering implicit bias workshops and anti-racism training, as multicultural education gave way to the concept of culturally responsive pedagogy or practices.

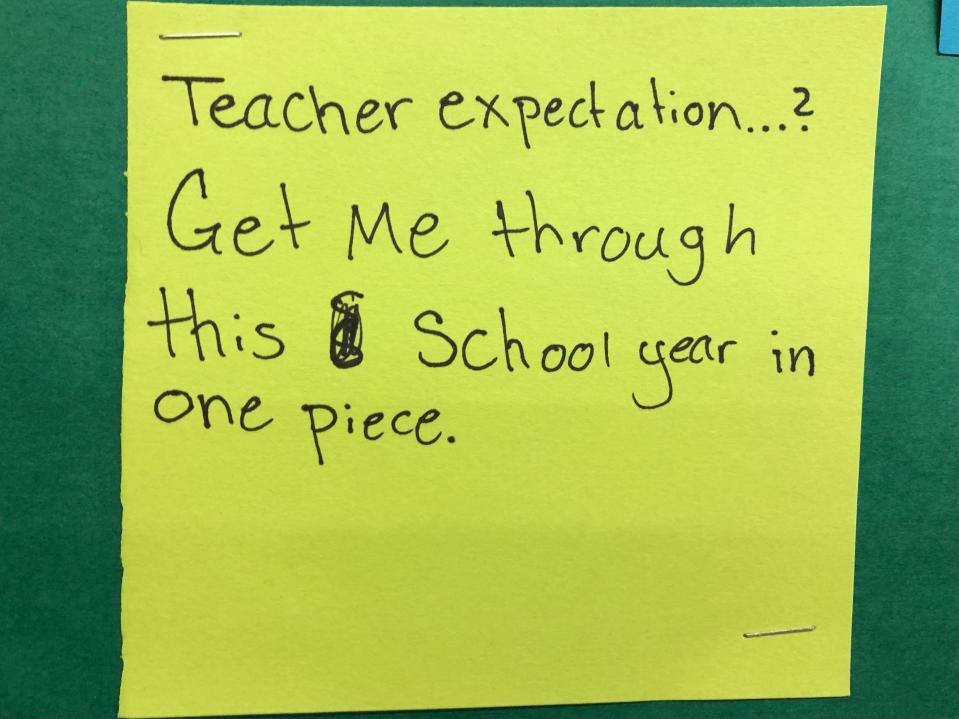

“The teachers often feel like professional development is a series of new buzzwords that they’re going to try and a year on, it will be replaced with a new initiative,” said Andrew Matschiner, a visiting assistant professor at Miami University in Ohio, who recently published a systematic review of professional development addressing race and racism in the journal Review of Educational Research. “It’s really important that districts and schools present PD as part of a solid commitment that’s going to be embedded in everything they do versus something they want teachers to learn right now and we’re not going to come back to it.”

Regardless of the names of the teacher trainings, the end goal remains the same: to use public education as a means of leveling historic inequities in achievement across racial groups. One challenge: The majority of teachers are white women, while the majority of students are children of color. Of the 49.4 million U.S. public school students, 45% are white, 29% are Hispanic,15% are Black, 5.5% are Asian, and 4.7% are multiracial. And most of those teachers feel unprepared to work in racially diverse settings, according to research by scholars including Rita Kohli, an associate professor at the University of California, Riverside.

What the survey found

Of the school districts surveyed, 60% require educators to take some form of equity-oriented training, with the remaining districts offering it voluntarily. While training is offered most frequently to classroom teachers and administrators, about 1/3 of districts even provide it to maintenance staff, bus drivers and family members. This is significant because many incidents that result in disciplinary action take place outside the classroom: in hallways, on the playground or on the bus.

Nashville, Tennessee, school leadership aims to have every classroom teacher and administrator take a six-hour training on the foundations of diversity, equity and inclusion, of which half is in person and half is online, said Ashford Hughes, executive officer for diversity, equity and inclusion. The training brings together teachers from different buildings and areas of the city to learn together. They reflect on their own mindset and practices as they discuss ways to fight bias, how to connect with students from racial and religious backgrounds different from themselves, and specific changes to their educational practices.

“We all are colleagues in the championing of public education for our students, so we wanted to break down those walls of discomfort,” Hughes said, noting the tendency towards “Nashville nice” in avoiding difficult topics like race and socioeconomic inequity. The training intentionally challenges preconceptions, while acknowledging that not every educator will be ready to change. “We’re not there to argue anyone down.”

About those anti-DEI bills: Higher ed leaders have largely kept mum. A new campaign changes that.

Nearly half of the districts surveyed mentioned Glenn Singleton’s Courageous Conversation framework as a source of training, followed by the professional associations Learning Forward and ASCD. We received responses from 42 districts across the country, which enroll over 3 million students collectively, after inviting the 100 largest public school districts to share their practices in a 34-question survey or a telephone interview.

Many of the responses showed a deep investment in shifting educators’ practices and an understanding of how difficult the task is. “We have district-wide implicit bias training for all 73,000 employees including anyone and everyone that works in the district – people who work in our kitchens and are cleaning our facilities,” said Alison Yoshimoto-Towery, then-chief academic officer of Los Angeles Unified School District, who now leads a statewide learning collaborative. “We know one-shot professional development doesn't work. There's been years of studies that show coaching is a key component to professional development.”

How do districts assess whether training is effective? Not systematically, the survey found. Some merely ask participants about their experiences. Others collect student data or observe classroom instruction. But none used the gold standard: evidence from a controlled study or trial of that training. The profession simply doesn’t have the scientific data, experts said.

“We’re in the early stages of understanding the impact of multicultural professional development,” said Hillary Parkhouse, an associate professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. “People are going to receive it so differently; we’re still learning a lot about how teachers change their beliefs.”

Jagemann, Milwaukee’s discipline manager, recalled a white educator who started off in a training by saying: “Let me know when we’re going to start blaming white men, and I’m ready!” One of the two facilitators pulled him aside a bit later, when there was a break, and asked him to share more about that comment. “She did a very good job of defusing,” said Jagemann. Other times, it can get tense when white participants share experiences of bullying or hardship. “We always come back to: That’s that individual’s truth and that’s OK. We’re not diminishing your opinion.”

A new approach to equity helped a dozen-plus schools in Fayetteville, North Carolina, move out of low-performing status during the pandemic, according to Jovan Jones, equity and opportunity coordinator. Jones attributes the improvement to high-impact tutoring, leadership coaching and the district’s systems approach to equity. In 2017, Jones incorporated equity and trauma-informed practices into the district’s classroom management intensive course, so teachers can better understand when children are in fight-or-flight mode and need to self-regulate in order to learn. That mindset helps reduce suspensions and expulsion and keep students in the classroom, which both improves learning outcomes and lowers discipline disparities.

With the help of the SWIFT Education Center at the University of Kansas, the district created five learning modules to educate teachers about equity; the first two are mandatory and the others are optional. “It’s a huge step forward,” Jones said, noting that they were sent to all employees in early August. “We've had really good feedback so far.”

One district uses student surveys to assess the impact of programs aimed at inclusion and belonging. In Detroit, every school identifies a staff lead for equity professional development and the district holds monthly support meetings for those professionals as well as organizing equity book clubs, according to Naomi Khalil, senior executive director of equity and culture for Detroit Public Schools. Khalil holds weekly office hours to support staff on equity topics and uses the Panorama Education school climate survey and its Loved, Prepared and Challenged index to assess the impact on students. “We offer a robust set of equity trainings, from identity and bias to courses on power and privilege, trauma and healing, religion, language, gender and culturally responsive teaching and learning,” Khalil said in her survey response.

Schools should recruit teachers of color, insist on high standards

In part, the lack of hard evidence for equity-oriented professional development reflects the reality that it’s difficult to measure what’s in teachers’ hearts and minds. Moreover, every district, school and classroom includes slightly different dynamics.

Experts called for a deeper approach to equity that incorporates more than just teacher training. School districts should build better pipelines for recruiting teachers of color and work to create workplace cultures that encourage them to stay. Most important: Leaders can narrow disparities by integrating equity throughout the curriculum and focusing on challenging instruction.

In Jacksonville, Florida, the district had worked with author Sharroky Hollie to give educators tools for making the curriculum relevant to students of color and with diverse backgrounds, said Paula Renfro, chief academic officer for Duval County Public Schools. “Those strategies are integrated directly in content area instruction and then we also offer standalone professional development support for our teachers, administrators and support staff,” Renfro said.

In 2018, a report from The New Teacher Project found that 80% of teachers are teaching below grade level, as measured against state and federal standards for each grade. That worsens racial achievement disparities. In response, Duval County joined a growing number of districts that aim to deliver all instruction at the actual grade level and provide support for students performing below that standard, Renfro said. Educational leaders observe classroom instruction with an eye to this question: Are the teachers giving instruction at grade level or dumbing it down?

Teachers must maintain high expectations for all students, and accelerate learning instead of assuming that the best they can do is catch up, said Nancy Brightwell, chief academic officer for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina. Every training begins with educators examining their positions of power and privilege. “Whatever professional development we lead starts with an opportunity for self reflection about our own biases, places where power shows up in our instruction,” said Brightwell, who brought a team of Charlotte educators to the nonprofit UnboundEd’s five-day training last year.

The training, at the Mandalay Bay conference center in Las Vegas, began as a vibrant celebration of teachers. For the opening session, participants entered the ballroom between two lines of UnboundEd staff and feather-hatted show girls cheering and waving pompoms to a playlist of Kool & the Gang, Bruno Mars and Beyoncé. Chief Executive Officer Lacey Robinson took the stage in a shimmering pink coat-dress cinched with a rhinestone studded belt. She praised teachers as the frontline responders of the pandemic, who lifted the atmosphere for students and supported their mental health. By the end of her keynote address, her tone changed. She exhorted attendees to be bold in their speech and actions to create equity in their classrooms and keep teaching at grade level despite students’ learning gaps.

“The disease in education is the predictability of student achievement by race,” said Robinson. “Yes, we know they have unfinished learning. But if we put them on roundabouts of previous years of lessons and units, they will never get on the on ramp. If you say to yourself, ‘I don't know how to get them on the on ramp,’ this is the week to learn.”

Since its founding in 2015, UnboundEd has seen its summits grow from 500 attendees to more than 2,000 educators learning how to teach at the grade-level standard while also centering equity. Unlike many diversity trainings that are add-ons to the curriculum, UnboundEd weaves equity throughout the curriculum. Educators hear rousing keynotes and then break into subject and grade-level groups for the whole week. They work both to understand biases they might bring to the classroom and to learn strategies for counteracting those beliefs. They learn ways to supplement students’ knowledge and abilities in order to teach at the grade level, no matter what tests show about the students in the room. They leave the summit charged with holding high expectations for every student and honoring each child’s identity and cultural background, as a crucial foundation for engaged learning.

In a breakout group on elementary school English/Language Arts, one third-grade teacher shared that early in her career, she thought, “These kids aren’t ready” to be taught at the national standard for third grade. Through the training, she realized the bias she’d internalized, and rose to the challenge of supporting any child in her classroom to understand and master the grade-level material. Other educators in the room nodded agreement, and the conversation continued about strategies for clarifying complex concepts and helping students decode words. UnboundEd challenges teachers to offer regular practice with complex texts so students can read, write, speak and listen with reference to textual evidence.

“We are starting to help our nation reimagine what it means to be a teacher,” Robinson said in an interview, noting that all facilitator pairs include at least one person of color. UnboundEd’s goal is for “every student to receive grade level, engaging, affirming, meaningful instruction. We're not a social justice organization. We believe justice is in the details of teaching and learning.”

Teacher training is only part of the solution

Talking about race, breaking down bias, adopting culturally relevant curriculums and teaching at grade level are important for equity. But they’re just the beginning of what’s needed, according to researchers and scholars. Another challenge is diversifying the majority white female teaching corps. Districts are looking at effective ways to recruit teachers of color and – more important – to create school cultures that retain those educators long term. Other issues include teaching English language learners in an increasingly diverse nation, and trauma-informed instruction and discipline practices.

In Columbus, Ohio, leaders seek to shift the focus beyond the words educators use in the classroom and programs targeting specific at-risk groups. Educators sometimes think: “If we can just put in this mentoring program or tutoring, that will solve the problem,” said former Chief Equity Officer Dionne A. Blue, who left the district in July to work for YWCA. “Really the problem is bigger and deeper and more systemic and that’s where we should be focusing our time and resources.”

Rather than teaching specific content about Black boys or a culture that’s new to some educators, Blue seeks to build their skills at connecting with those different than they are and increase their comfort level with uncomfortable topics. Equity needs to be infused in everything from curriculum to discipline to support services, she said.

In Massachusetts, an initiative to build anti-racist competencies at the principal level seeks to transform school cultures both for students and for educators in order to eliminate racial gaps in opportunity and outcomes. The thinking is that leaders with these competencies will avoid common equity pitfalls like assigning new or less effective teachers to classes dominated by students of color. They’ll also be more effective in hiring and retaining Black and Brown teachers.

“Principals are the gatekeepers often of what goes into their school and what is kept out. ... It’s a huge opportunity to think about racial equity,” said Paul Fleming, chief learning officer at Learning Forward, a professional learning organization that helped create the principal training for Massachusetts. “Schools cannot exclusively solve and be responsible for solving systemic racism.”

How we reported this story

In spring 2022, the reporting team invited officials at the largest 100 public school districts in the U.S. to answer questions about their equity-oriented teacher training. Thirty-eight districts responded to the survey. An additional four made representatives available for phone interviews. All responses were received between March and July 2022, except for Dallas and Jefferson County, Colorado, which granted initial interviews in September 2021 but never completed the full survey, and Charlotte, which provided survey answers in August 2023. Another three districts provided data in September 2023 for the map graphic above.

Across the nation, a growing number of states have considered, and in some cases enacted, legislation in the last few years that restricts speech about race and gender in K-12 and college classrooms.

CONTRIBUTING: Rachel Ryan and Maureen Ojiambo, O'Brien interns. Andrew Hahn, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is a Washington, D.C.-area independent journalist and author who can be reached at info@KatherineRLewis.com or on social media. Rachel Ryan is a Milwaukee-based journalist. Maureen Ojiambo is a Sacramento-based journalist. Their reporting was supported by the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: As US schools become more diverse, patchwork equity efforts fall short