'Science of reading' is a gamechanger, but not enough Kansas teachers are trained

It took less than two minutes for Journee Freeman and Stevie Stinebaugh to prove they had lost little, if any, of the great reading strides they had made in kindergarten last year.

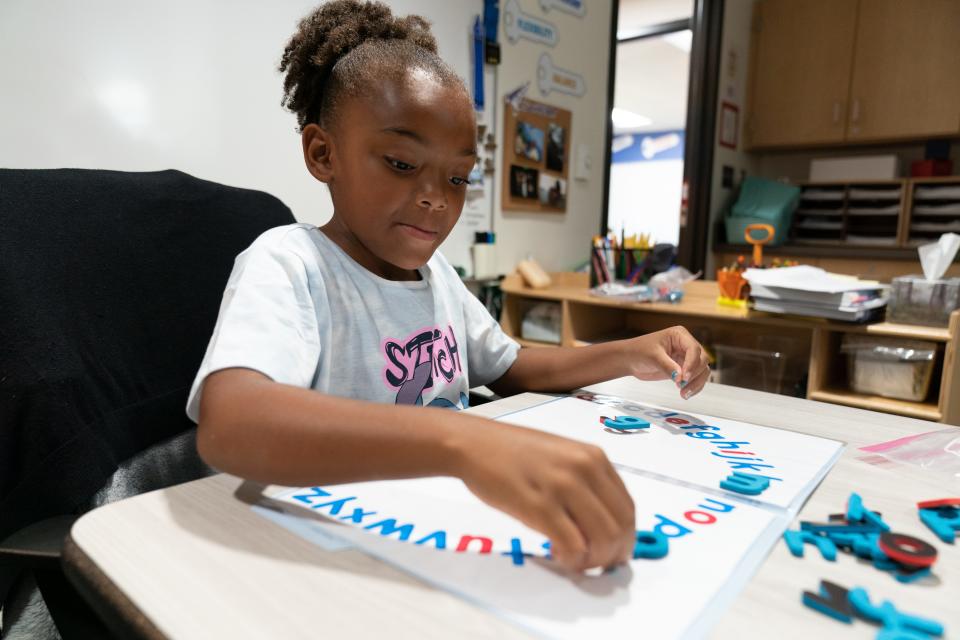

The two Berryton Elementary first-graders wasted no time sorting through the 21 consonants and five vowels on their alphabet arc poster boards, matching tactile foam shapes with the names and sounds they had learned to associate with each letter.

For Journee and Stevie, it was a happy little activity that they've made into a fun exercise that lets them practice the alphabet.

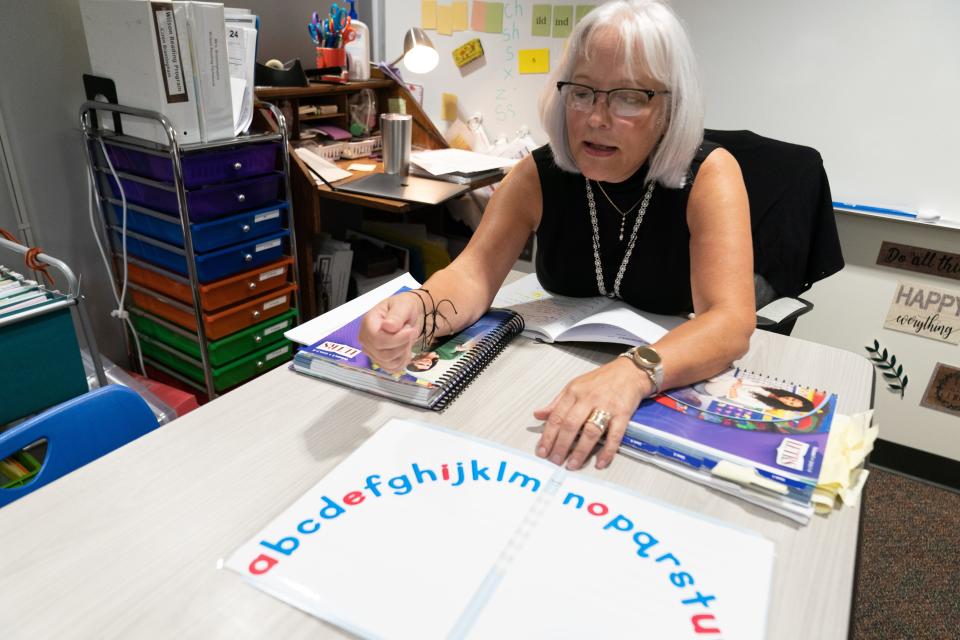

For school reading specialist Karen Brantingham, it was proof that a year of training and applied instruction in the science of reading is making a difference.

"It’s been a humbling experience (taking the training)," Brantingham said. "I’ve been teaching for 29 years, and I didn’t have that in my toolbox? It’s humbling. But nobody knew, and when you know better, you do better."

Brantingham and nearly 8,000 other Kansas elementary schoolteachers have in the past two years received at least some training under a $15 million state program to retrain educators in the way they teach students to read and write.

But that's only about half about the number of elementary school teachers who are eligible for the training, and education commissioner Randy Watson said teachers and schools across the state need to move more urgently to help students recover skills they lost or never picked up during the pandemic.

"We shouldn’t waste another day, when we have kids in school now, and we have federal money that the state board is using to help from a learning loss perspective," Watson told The Capital-Journal.

KSDE is embracing the 'science of reading'

In broad strokes, the "science of reading" refers to modern research that shows educators not just what to teach in literacy education, but also how young students make connections in their brains in using and applying early literacy skills.

So-called "reading wars" over the past several decades have often led to different conclusions as to the best way of teaching kids to read, with many including the same concepts but with different levels of priorities.

For example, most older teachers in Kansas were taught mixtures of whole language and balanced literacy, which generally put a bigger focus on the meaning of words and texts and students' ability and enthusiasm to comprehend them.

But critics of those approaches argued that they did not place enough of an emphasis on fundamental skills like phonics and phonemic awareness — or the ability of students to read, identify and use basic letters and sounds in words.

More: Universal free school lunches ended, but some Kansas schools see a way to keep food coming

The "science of reading" prioritizes those skills in literacy instruction. Students get systematic and explicit instruction in putting together letters and sounding them out, and teachers structure their lessons to make sure students are strong in those skills before moving on to other reading skills like fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

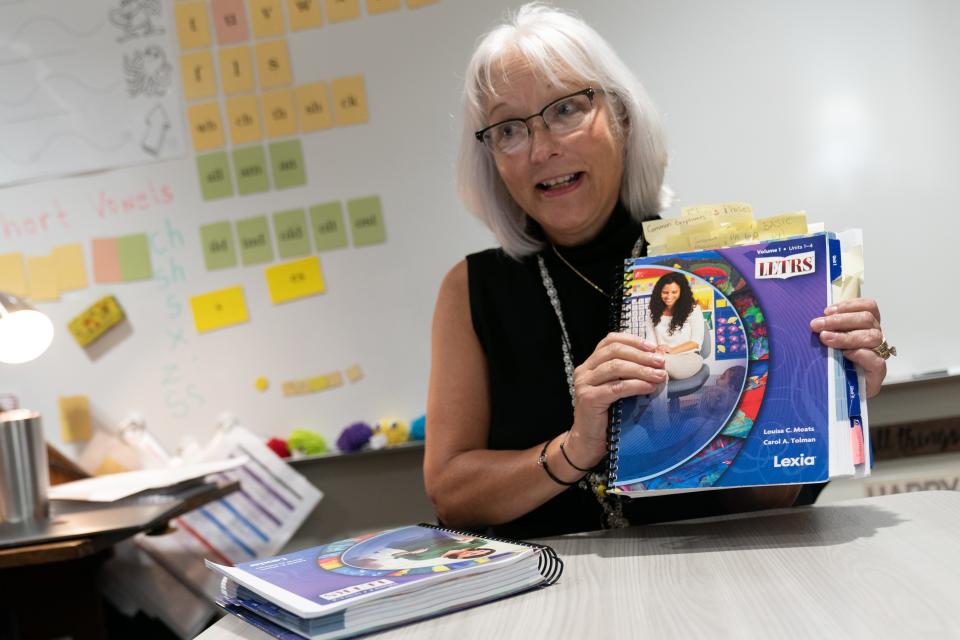

At the start of the pandemic, the Kansas State Board of Education funded a $15 million program to pay for any Kansas elementary school educator to receive training in the science of reading, through a national program called Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS).

For veteran teachers like Brantingham, the concepts in the LETRS training weren't necessarily anything new. Much of the training involved concepts she's learned on the job and as a college student more than 30 years ago.

But some pieces, and the priorities given to different skills, were eye-opening, she said.

"I did not realize how important it is for them to rapidly recall letter names and sounds," Brantingham said. "For years, we thought that the kids knowing the letters was enough, but just getting there is not enough. It needs to be automatic recognition, for them to process the alphabetic principles."

Kansas teachers need to move more urgently on science of reading, commissioner says

The Kansas State Board of Education, as one of its goals, earlier this year challenged schools across the state to move more kids out of level 1 on the Kansas state assessment. Students who score in that category, per assessment definitions, show a limited ability to demonstrate the knowledge and skills necessary for success after high school.

While that score is based on a single test taken in the spring, Watson has often pointed out that students who score at level 1 early in their academic careers struggle to reach other success in later years of school.

Reading skills are crucial to getting students out of Level 1, since most other learning is based on a student's ability to read and comprehend the texts they are given, Watson said.

Literacy education then, he said, has to be at the forefront of Kansas schools' efforts to improve academic achievement, especially after many students lost learning opportunities during COVID.

More: Academic improvement is ‘first and center’ in Kansas State Board of Education’s proposed goals

The rate of Kansas students achieving at levels 3 and 4 — levels showing effective and excellent skills — on the state English language arts assessment fell to a low of 32.1% in spring 2022, although preliminary data from this spring shows the beginnings of a rebound.

Watson said elementary schools and teachers need to move more urgently on literacy, especially since only about half of eligible teachers have taken or begun the two-year LETRS training. The federal funding backing the state's offer of LETRS training expires in just over a year.

"COVID is no longer with us, and in September 2024, guess what happens to that money?" Watson asked the state education board. "It’s gone. Just a year from now, it’s gone. There’s $9 million left to be spent training teachers, and I have to have a belief we can do the work. We can’t change beliefs, but we can help impact that."

Much of the hesitation is believed to be from teachers who are finding it difficult to sign up for a relatively intense two years of training, state officials said.

More: Can Kansas high school bands, choirs and orchestras rebound from COVID-driven drop-off?

For many teachers, taking the training requires much more than personal will. It requires availability of substitute teachers to cover while they're gone, at a time when schools are struggling to staff support positions. It requires an additional few hours every week for two years, when time is in short supply between lesson planning, teaching and grading. It requires administrative support, when principals and superintendents are managing any number of other school issues.

"It’s free," Watson stressed. "It’s two years of training, and it’s hard. This is intense training. But if we’re going to have every student be literate, be able to read and be functional above level 1, we’ve got to believe that we can do the work with every kid. That’s No. 1. Then we have to have the skill to it, and then we have to have the will to put that skill into action every single day, choose the right curriculum and do those things."

Some Kansas school districts, though, have embraced the training, like Shawnee Heights USD 450, where Brantingham works.

There, the district paid teachers an additional $1,200 stipend for each year of the training they completed. Twenty-two teachers completed LETRS last year, with a further 45 undergoing the training this year.

Brantingham, a seasoned reading specialist, knows the science of reading training won't be a magic solution for all students. Nothing in education ever is.

But she's confident she and her fellow teachers are open to learning new approaches and always doing better by their students."

"Nobody teaches in isolation anymore," Brantingham said. "We teach together, and we watch each other teach. We collaborate. There’s nothing done quietly in your room with the door shut. It’s a lot easier to see the good stuff that is going on, and I have to believe there are teachers who will change and shift when they need to."

Rafael Garcia is an education reporter for the Topeka Capital-Journal. He can be reached at rgarcia@cjonline.com or by phone at 785-289-5325. Follow him on Twitter at @byRafaelGarcia.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Kansas' LETRS science of reading is training teachers in literacy