Scientists believe they can predict the Sun’s solar storms to protect satellites, power grids and the internet

Scientists have developed a new way to predict the strength of solar cycles – the time at which the Sun’s power increases and decreases over a decade.

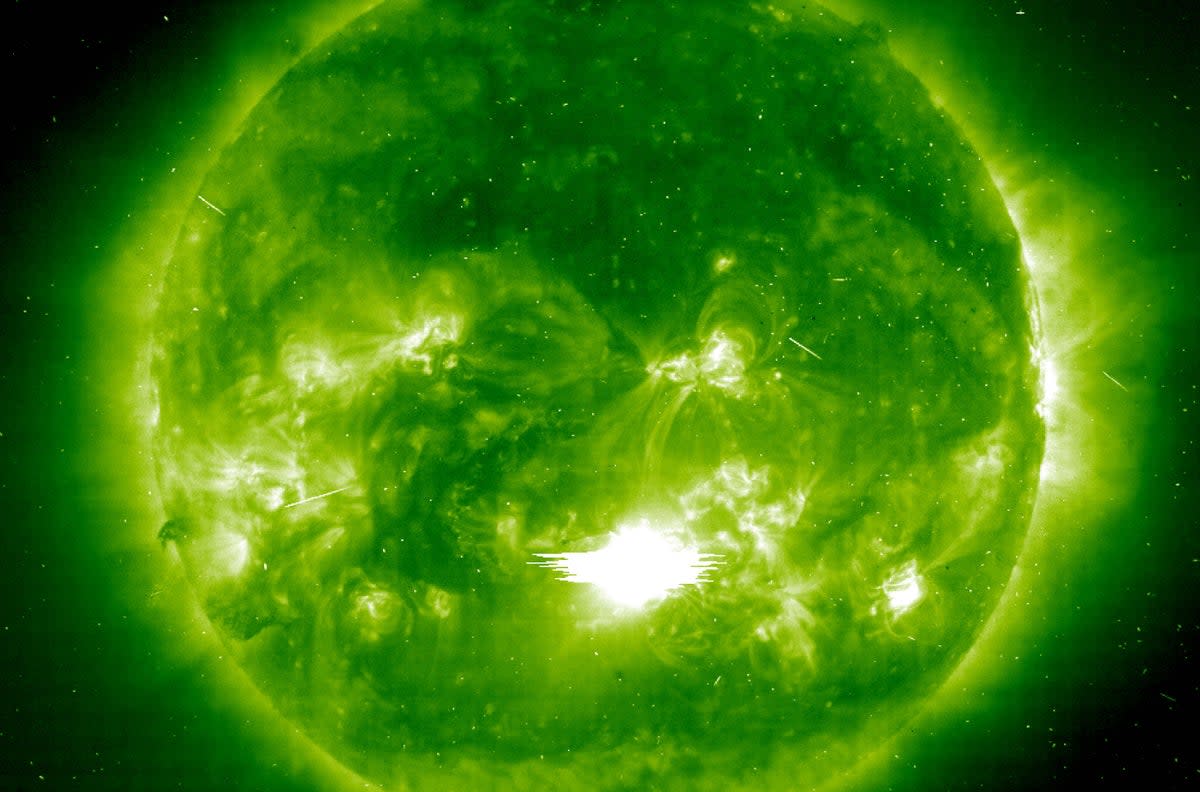

The powerful flares from the Sun come from sunspots, which appear and disappear approximately every 11 years. These are hubs of magnetic forces that have risen from the solar interior, usually coming in pairs like a magnet; one is positive, and the other is negative.

These eruptions are capable of releasing 100,000 times more energy than all the power plants on Earth generate throughout a year and have often been the cause of trouble for satellite launches.

SpaceX recently had 40 satellites knocked out of orbit during a solar storm, and many smaller CubeSats did not make it to their destination – at a cost of around $50 million.

Over the past year, the European Space Agency’s Swarm constellation – which measures magnetic fields around Earth – started dropping in the atmosphere 10 times faster than before.

“In the last five, six years, the satellites were sinking about two and a half kilometers [1.5 miles] a year,” Anja Stromme, ESA’s Swarm mission manager, said.

“But since December last year, they have been virtually diving. The sink rate between December and April has been 20 kilometers [12 miles] per year.”

But there may now be a way of predicting these cycles, as the maximal growth rate of sunspot activity is a precursor to how powerful the cycle might be.

Moreover, predictions about the solar cycle are more accurate when the two hemispheres of the Sun are considered separately, rather than collectively.

"The solar magnetic field is the driver of the 11-year solar cycle and of energetic eruptions from our sun. We have learned from our study that we can obtain more accurate predictions of solar activity when using hemispheric sunspot data, which capture the asymmetric and out-of-phase behavior of the solar magnetic field evolution in the north and the south solar hemispheres," said study co-author Astrid Veronig, professor at the University of Graz, and head of the Kanzelhöhe Observatory for Solar and Environmental Research, to Phys.

The study allowed scientists to determine the evolution of the cycle and help engineers on the ground prepare for an extreme weather event – such as those that could disrupt power grids, communication equipment, and the internet.

Once every century, due to the Sun’s natural life cycle, solar winds escalate into solar superstorms that could cause catastrophic internet outages; unfortunately, our own infrastructure is not completely protected against that.

“In today’s long-haul Internet cables, the optical fiber is immune to GIC. But these cables also have electrically powered repeaters at ~100 km intervals that are susceptible to damages,” Dr Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi, from the University of California, said. “We have no idea how resilient the current Internet infrastructure is against the threat of [coronal mass ejections]”.