Scientists cook ‘alien haze’ that could help us find extraterrestrial life

Scientists have cooked up the "alien haze" of distant planets, in an effort to help with the search for alien life.

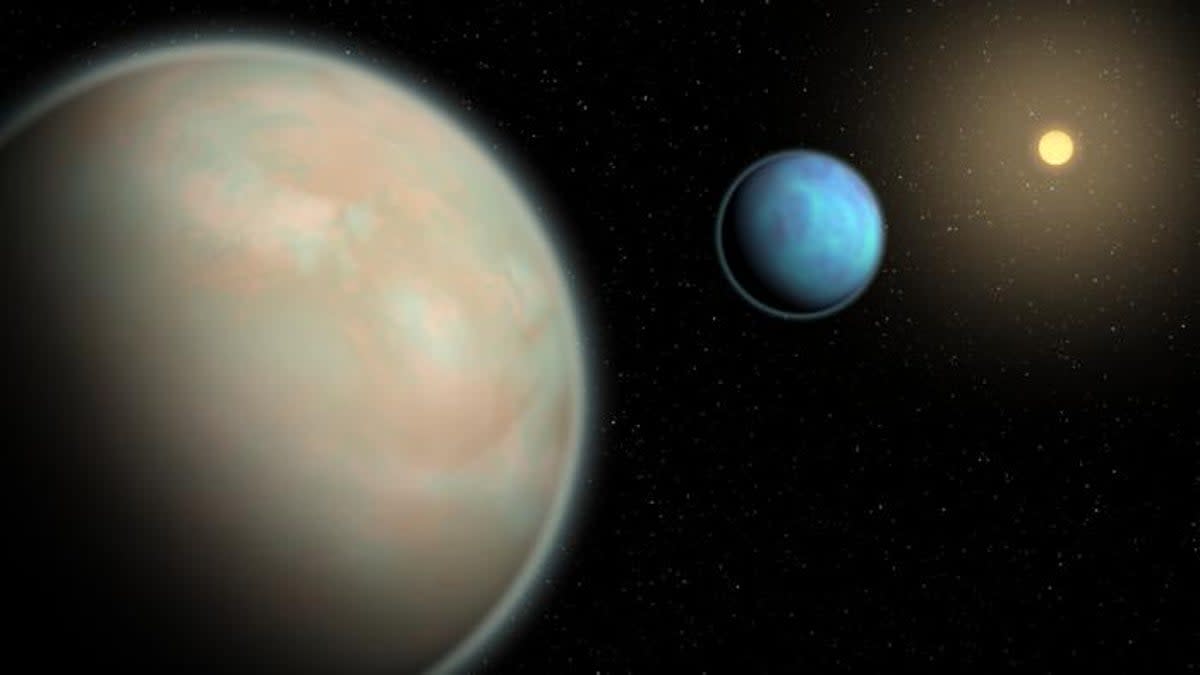

The haze is a simulation of the hazy skies that appear on water-rich exoplanets, or worlds outside of our solar system. That haziness can get in the way of observations of those planets, making it difficult to understand what is happening there.

Haze can also affect conditions on the planet themselves. If the atmosphere has hazes or other particles then it can drastically change the temperature, amount of light an other factors – some of which might be make or break for alien life there.

Scientists hope the homemade haze will let them better understand the atmospheres of other planets, and model how the planets themselves form and grow. They could allow us to better understand how the have distorts our picture of those planets – distortions that could give us the wrong understanding of the makeup of their atmospheres.

Getting that wrong could mean potentially missing habitable worlds, for instance. The observations are used to come up with the estimates about the temperature and atmospheric conditions that are then used to determine whether a planet might be able to host alien life.

“The big picture is whether there is life outside the solar system, but trying to answer that kind of question requires really detailed modeling of all different types, specifically in planets with lots of water,” said co-author Sarah Hörst, from Johns Hopkins University. “This has been a huge challenge because we just don't have the lab work to do that, so we are trying to use these new lab techniques to get more out of the data that we’re taking in with all these big fancy telescopes.”

The team cooked up the haze using a custom-designed chamber in Hörst’s lab. The haze they made is formed out solid particles, suspended in gas, which changes how light interacts with the gas itself.

To test the hazes they made, scientists shot ultraviolet light through them, measuring how much they absorbed and reflected. They found that hate haze matched the chemical signatures of a well-studied exoplanet.

Scientists hope to develop yet more hazes, with different gas mixtures, that will let them better understand different atmospheres.

The work is described in a new paper, 'Optical properties of organic haze analogues in water-rich exoplanet atmospheres observable with JWST', published in the journal Nature Astronomy.