Scientists Discover Molten Layer of Rock Beneath Earth's Crust

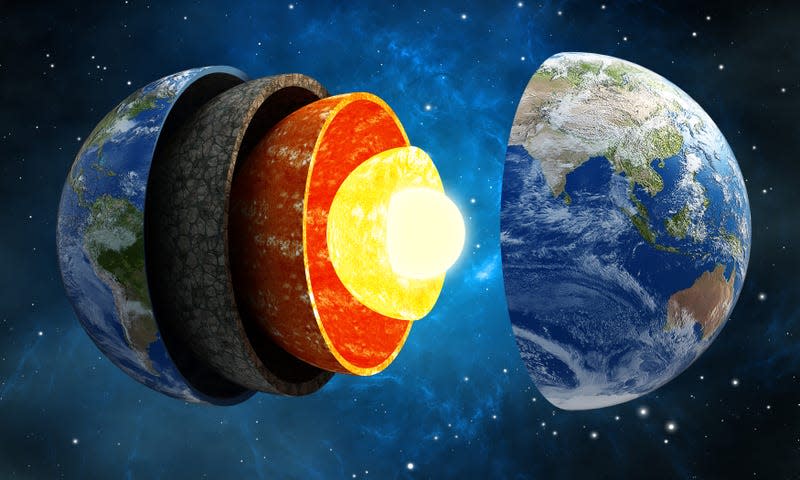

Earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are a result of the movement of large swaths of Earth’s crust, but while the theory of plate tectonics has been widely accepted as a fundamental law of geology, there are still things to be discovered. New research from the University of Texas Austin points to the presence of a partly molten layer of rock underneath Earth’s surface that could provide some explanation for how the plates move like they do.

The layer is about 100 miles (160 kilometers) below Earth’s surface, and while scientists have found patches of melt at this depth previously, new research published in Nature Geosciences indicates that molten rock could be more widespread. Through analysis of seismic data, a team led by Junlin Hua identified that the molten layer—which belongs to the upper part of the mantle, called the asthenosphere—probably has little to no bearing on how Earth’s tectonic plates move over the mantle.

Read more

These Winning Close-Up Photos Show Life That's Often Overlooked

Remembering Enterprise: The Test Shuttle That Never Flew to Space

“When we think about something melting, we intuitively think that the melt must play a big role in the material’s viscosity,” said lead author Hua, a postdoctoral fellow at University of Texas Jackson School of Geosciences, in a press release. “But what we found is that even where the melt fraction is quite high, its effect on mantle flow is very minor.”

The mechanism that helps fuel the motion of Earth’s tectonic plates is one of the great mysteries of geology. Hua and his colleagues’ research suggests that convection currents in the mantle could be the cause. While the interior of Earth is mainly solid, the mantle can be thought of as an incredibly viscous liquid, that shifts and flows over long periods of time.

“We can’t rule out that locally melt doesn’t matter,” said Thorsten Becker, a co-author on the paper and a professor of geology at University of Texas Austin, in the release. “But I think it drives us to see these observations of melt as a marker of what’s going on in the Earth, and not necessarily an active contribution to anything.”

For a planet that is 4.5 billion years old, Earth is still full of surprises.

More from Gizmodo

Sign up for Gizmodo's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.