Scientists discover mysterious ‘islands’ in seas of Saturn’s moon are actually organic matter

Strange disappearing “magic islands” spotted by Nasa’s Cassini spacecraft on Saturn’s moon Titan are actually blobs of organic molecules floating in seas of liquid methane, scientists say.

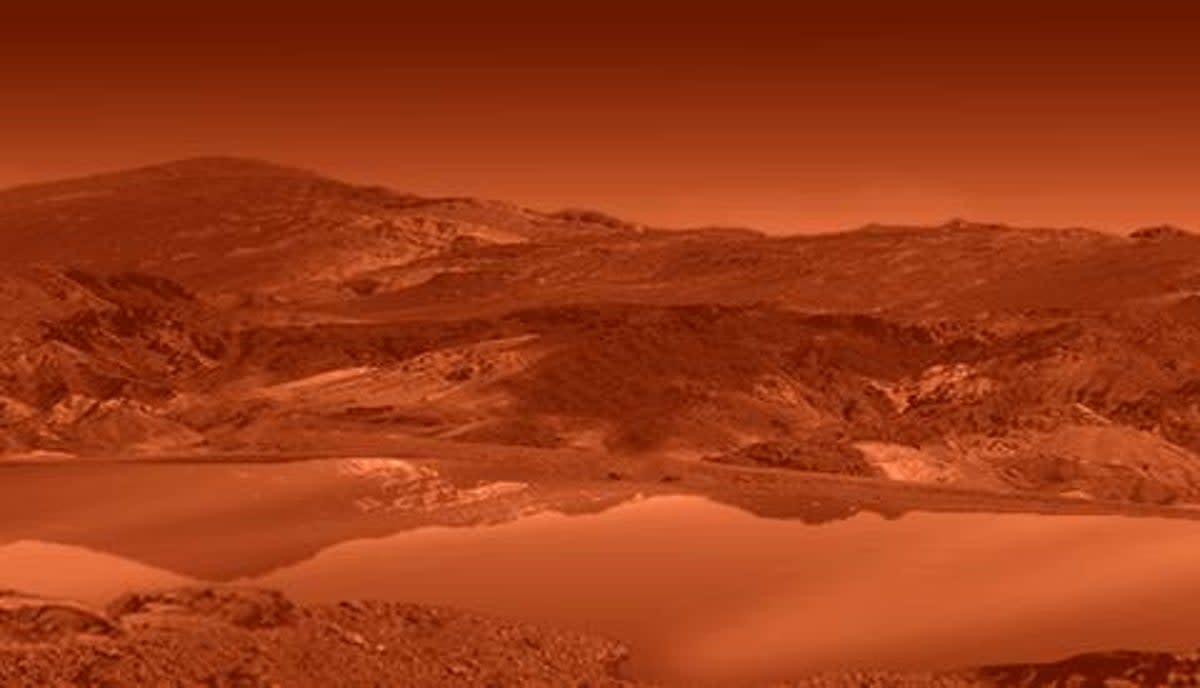

When the Cassini spacecraft conducted radar scans of Titan, it found that the moon’s surface was covered with dark dunes of organic material and seas of liquid methane.

The Nasa probe also found strange shifting bright spots on the seas’ surfaces lasting a few hours to several weeks or more.

These disappearing “magic islands” were first spotted in 2014 and scientists have since been trying to figure out what they are.

Researchers previously theorised these could be phantom islands caused by waves, or real islands made of suspended solids.

The new study, published recently in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, assessed the connection between Titan’s atmosphere, its liquid lakes, and the solid materials deposited on the moon’s surface.

The moon’s hazy orange atmosphere is known to be 50 per cent thicker than Earth’s, rich in methane and other organic molecules.

“I wanted to investigate whether the magic islands could actually be organics floating on the surface, like pumice that can float on water here on Earth before finally sinking,” study lead author Xinting Yu said in a statement.

Scientists found that carbon-based, organic molecules prevalent in Titan’s upper atmosphere can clump together, freeze, and fall onto the moon’s surface – including onto the moon’s rivers and lakes of liquid methane.

Since these lakes are already saturated with organic particles, researchers found that the solids falling from the atmosphere do not dissolve when they reach the liquid.

“For us to see the magic islands, they can’t just float for a second and then sink. They have to float for some time, but not for forever, either,” Dr Yu said.

The seas and lakes are also methane-rich with low surface tension, which makes it harder for the solids to float.

While the individual solids from the atmosphere are likely too small to float by themselves, computer simulations suggest that if the solids were large enough, and had the right ratio of holes and narrow tubes, the liquid methane could seep in slowly enough for the clumps could linger at the surface.

But if enough clumps massed together near the shore, scientists say the larger pieces could break off and float away, similar to how glaciers calve on Earth.

The combination of a bigger size and the right porosity of the organic solids explain the magic island phenomenon, scientists say.