Scientists Learned How to Reconstruct Long-Extinct Animals

Researchers from the University College Cork in Ireland have discovered a new way to reconstruct the anatomy of ancient vertebrates by tracing melanin, which builds a map of a specimen's internal organs and soft tissue.

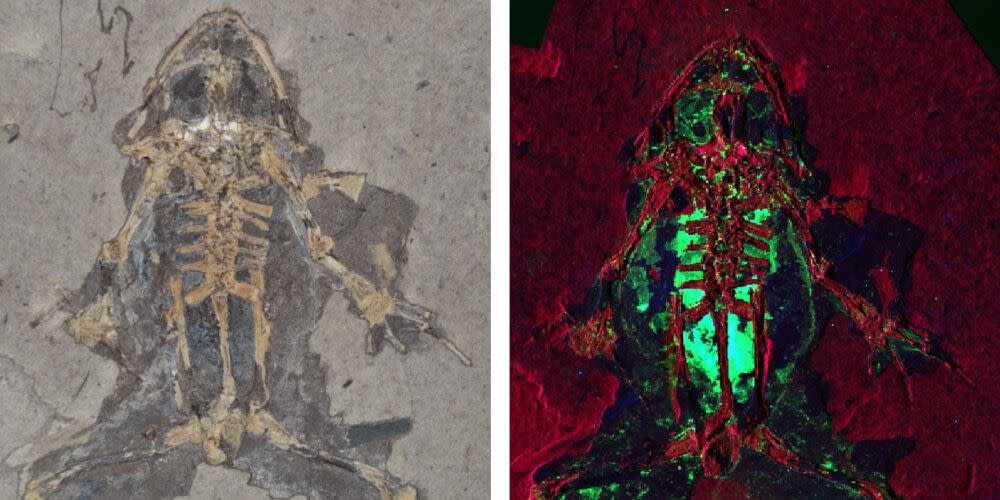

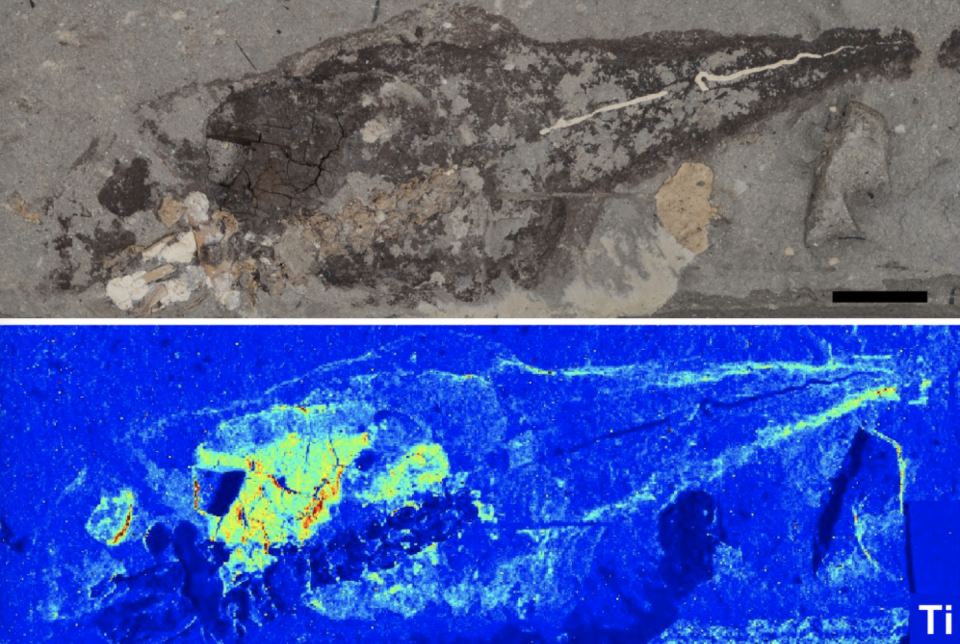

The team analyzed 10- and 50-million-year-old fossils in incredibly vivid scans showing traces of metals such as titanium and melanin pigments.

Researchers at University College Cork (UCC) in Ireland have figured out how to reconstruct the bodies of extinct vertebrates by "analyzing the chemistry of fossilized melanosomes from internal organs."

Melano-what? We'll explain.

Melanosomes are organelles (structures that perform specific tasks within cells) where melanin is synthesized, stored, and transported. Melanin, meanwhile, is the pigment that colors the hair, feathers, skin, and irises of animals.

According to Ananya Mandal, M.D., tyrosine, an amino acid that synthesizes proteins, only exists in melanocytes—melanin cells—where the melanin pigment is housed in vesicles known as melanosomes. Melanosomes move from the melanocytes to different cells, like the epidermis, and deposit the pigments that give us the color of our skin, hair, and eyes.

A study published in the Proceedings in the National Academy of Sciences by researchers from UCC found that "internal melanosomes are widespread in diverse fossil and modern vertebrates and have tissue-specific geometries and metal chemistries."

The study was led by Valentina Rossi, a Ph.D candidate at UCC, and Maria McNamara, Ph.D., a paleobiologist and senior lecturer of geology at the university. Rossi and McNamara worked with a team of chemists from the U.S. and Japan using a synchrotron—an electron accelerator—to analyze the chemistry makeup of fossils.

Even though "diagenetic overprint"—the loss of some physical and chemical integrity as an organism fossilizes—deteriorates some of the specimen, the team at UCC was able to reconstruct the anatomy of some soft tissues in fossil vertebrates. The team could also discern various uses for melanin in these prehistoric animals by "analyzing the anatomical distribution, morphology, and chemistry of melanosomes in various tissues in a phylogenetically broad sample of extant and fossil vertebrates."

The study revealed that there are large amounts of melanin in the internal organs of animals such as birds, reptiles, mammals, and "their fossil counterparts," which helped researchers reconstruct organs and tissues in prehistoric specimens in a way that's never been done before.

"The exciting point here is why would animals have melanosomes—that normally produce coloration in skin, feathers and hair—in their internal organs?" Rossi tells Popular Mechanics.

Meanwhile, McNamara says in a press release that the discovery is remarkable "in that it opens up a new avenue for reconstructing the anatomy of ancient animals. In some of our fossils we can identify skin, lungs, the liver, the gut, the heart, and even connective tissue."

Rossi and McNamara's team studied 10 million-year-old frog and tadpole fossils and the almost 50-million year-old fossils of a marine reptile and prehistoric bat using trace element chemistry.

"We think that the chemistry of melanosomes is the key to understanding fundamental physiological function of melanin within the body, like the regulation of metals in different internal organs," Rossi tells Popular Mechanics. "Because these melanosomes have tissue-specific metal signatures, we can reconstruct the soft tissue anatomy of fossils."

You Might Also Like