Scientists take a peek below Antarctica's 'doomsday glacier'

Antarctica’s rapidly melting “doomsday glacier” is one of the most closely studied masses of ice in the world, but new research by teams that used an underwater robot to swim beneath the floating ice shelf is providing some of the clearest insights yet into how the glacier is thinning from below.

Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica earned its nickname because it has been shrinking at an alarming rate as the planet warms. Previous studies have found that the glacier could collapse within 100 years, and meltwater from the Florida-sized mass of ice could raise global sea levels by up to 2 feet.

Scientists are keen to understand where and how Thwaites is losing ice because the glacier is often thought of as the canary in the coal mine for the consequences of global warming — a bellwether of the changing planet.

By looking beneath the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf, researchers were able to study how warm water is being channeled into cracks and crevasses and take key measurements where the ice meets the ocean. The findings, reported in two separate papers published Wednesday in the journal Nature, will help scientists better estimate what will likely happen as the glacier thins and paint a more detailed picture of how Thwaites is changing as a whole.

“None of this changes the trends we’ve observed about the rapid disintegration of the ice shelf,” said Britney Schmidt, an associate professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences at Cornell University and lead author of one of the studies. “Instead, this tells us not just how much melting is going on but where and how it’s happening under Thwaites in a very important part of the system.”

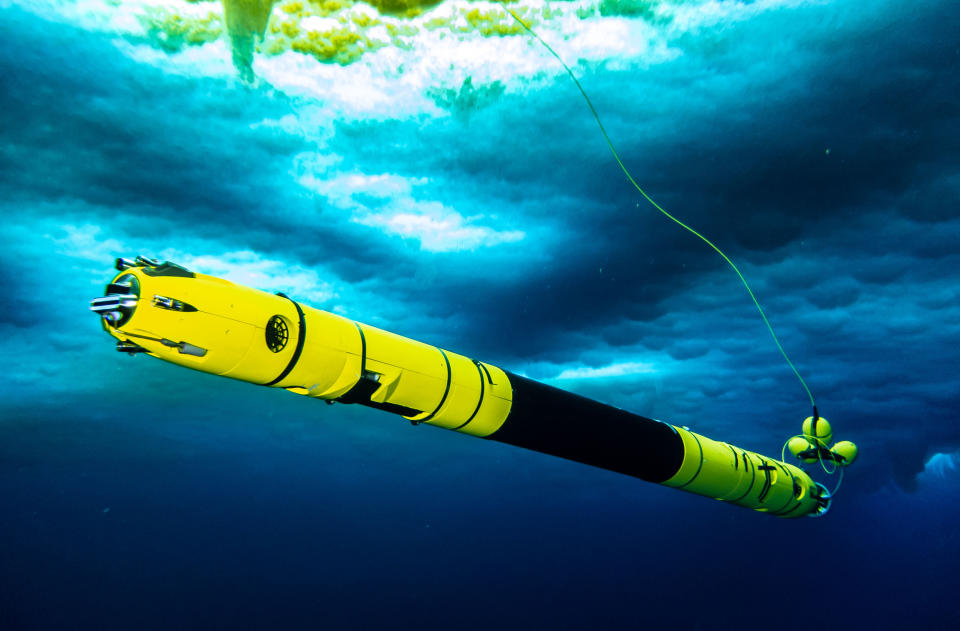

Schmidt and colleagues from Cornell, New York University, Pennsylvania State University and the British Antarctic Survey operated an underwater robot dubbed Icefin through a nearly 2,000-foot-deep borehole in the ice shelf.

The cylindrical-shaped drone spied crevasses in the ice base where warm water is penetrating and causing rapid melting. Crevasses are cracks that typically form as a result of stress on the ice as a glacier moves over land or juts into the ocean and weakens. The researchers observed crevasses filling with warm water, even at the glacier’s grounding line, where the ice first meets the ocean.

“They’re basically funneling warm water faster than other parts of the glacier system,” Schmidt said. “So, the crevasses are not just weaknesses in terms of cracks in the ice, but they are becoming these giant features, and that process starts right at the grounding line.”

Icefin also found long staircase-shaped features known as terraces across the bottom of the ice where significant melting is happening at different angles, she added. These features, along with the widening crevasses, are hollowing out the ice shelf from below and weakening glaciers at points that are already vulnerable to collapse, Schmidt said.

In a separate study led by Peter Davis of the British Antarctic Survey, researchers found that a layer of freshwater between the bottom of the ice and the ocean actually helps stabilize flat parts of the ice shelf. Melting in these regions was found to be slower than previous estimates using computer models.

“They’re still changing very quickly, but this helps us understand why some parts of the glacier act one way and other parts act another way,” Schmidt said.

And while Davis and his colleagues calculated a slower rate of melting underneath the ice shelf than previously thought, the findings still add to a concerning outlook for the glacier’s health. Thwaites’ grounding zone, where it meets the seafloor, has retreated almost 9 miles since the late 1990s, scientists have found.

“Our results are a surprise but the glacier is still in trouble,” Davis said in a statement. “If an ice shelf and a glacier is in balance, the ice coming off the continent will match the amount of ice being lost through melting and iceberg calving. What we have found is that despite small amounts of melting there is still rapid glacier retreat, so it seems that it doesn’t take a lot to push the glacier out of balance.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com