Scientists rally to rescue coral from unprecedented bleaching event in the Florida Keys

By the time a sensor in Manatee Bay recorded a water temperature of 101.1 degrees last month, coral scientists in the Florida Keys were already in the midst of a rescue effort that has been described as a cross between Noah’s Ark and the evacuation of Allied soldiers at Dunkirk.

To combat a coral bleaching event that has hit staghorn and elkhorn coral especially hard, divers have been undertaking the meticulous task of removing corals from offshore nurseries and, in some cases, the reef itself, for safekeeping in land-based coral nurseries, as well as temperature-controlled tanks in land-based aquariums.

At the same time, scientists will seek to learn from the conditions as they seek to breed resilient corals in the effort to restore the Florida Reef Tract as part of Mission Iconic Reefs.

Collapse of a symbiotic relationship

Cynthia Lewis, director of the Keys Marine Lab on Long Key – which is part of the Florida Institute for Oceanography at the St. Petersburg campus of the University of South Florida – noted that the sensor which recorded the 101.5 degree water on July 24 is only in four feet of water, tucked into a corner of Florida Bay.

Still, she’s seen dive computers record temperatures in the low 90-degree range, and many of the reefs researchers have been monitoring – and in many cases actively restoring – are experiencing water temperature warmer than 88 degrees, which had been more common in late August.

“At this time of year we expect it to be 85, 86 degrees,” she added.

Corals are actually colonies of tiny polyps that eat plankton. They live in a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae algae.

The algae feed off of the coral waste products and CO2 and provide the coral oxygen and organic products of photosynthesis. With that, the coral creates calcium carbonate, or limestone, which makes up a coral reef.

In years past, water temperatures would not hit the critical 88-90 degree range that could prompt a bleaching event until late August or September.

“We still have another four weeks to get to that point,” she added.

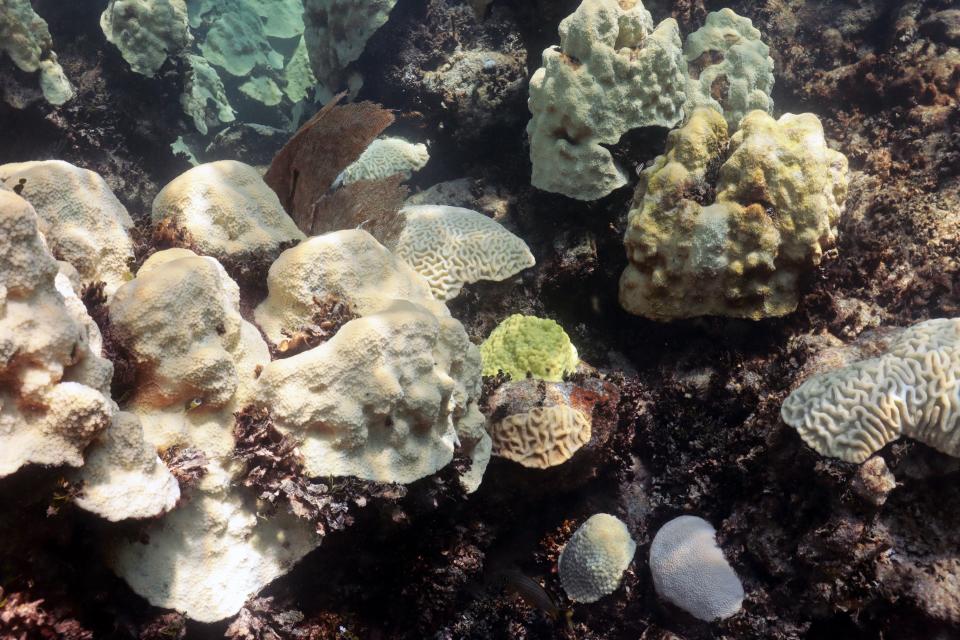

A combination of high temperature bleaching events, ocean acidification and disease has already taken its toll on the Florida Reef Tract – reducing the percentage of coral cover from 30% to 40% a few decades ago to anywhere from 2% to 5% – depending on the optimism of the scientists.

A temperature based timeline

NOAA Coral Reef Watch Director Derek Manzello noted in a July 26 release on the NOAA.gov web site, that coral bleaching can occur if ocean temperature is higher than the maximum monthly average by as little as 2 to 3 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1 to 2 degrees Celsius,

If ocean temperatures are higher than the maximum monthly average, for a month or more, especially during the warmest part of the year corals will experience bleaching.

That damage, he said, “is a function of the duration, or how long the heat stress occurs, plus the magnitude of the heat stress.

“Corals can recover from bleaching if the heat stress subsides, but the corals that are able to recover frequently have impaired growth and reproduction and are susceptible to disease for two to four years after recovery,” he added.

David Vaughan, founder and president of Summerland Key-based Plant a Million Corals, paraphrases Manzello’s thoughts as a one, two, three, rule: a good chance coral could come back after one month of bleaching, a poor chance after two months of bleaching and almost no chance after three months of bleaching.

Lewis pointed out that bleached coral aren’t dead, they’re just starving since the zooxanthellae no longer feed them.

“They still have the ability to feed and filter food from the water,” Lewis said. “Really what you’re seeing is the translucent skin of the coral and you’re seeing the white skeleton underneath it, which makes them look white.

“The skin is still there. It may be very very fragile and stressed with the heat but it’s still alive and can recover,” Lewis said, adding that some bleached coral brought into Keys Marine Lab are showing signs of recovery but they’ll likely be in recovery for a while.

Yet corals in the Florida Keys could be looking at more than three months of stressful conditions, unless repeated passes of tropical storms or hurricanes help cool the water.

That would be an unprecedented warming event, as available satellite records show most prior bleaching conditions lasted for four to six weeks.

Mission critical

In December 2019, the NOAA launched the $100 million Mission Iconic Reefs restoration program, with a goal of bringing the coral cover at seven iconic reefs to roughly 25% by 2035.

That came on the heels of back-to-back major bleaching events in 2014 and 2015 and the impact of Stony Coral Tissue Loss disease that started in 2014 and has since spread throughout the Keys.

Because of the infrastructure and partnerships formed in part to combat stony coral tissue loss disease and in part to carry out Mission Iconic Reefs, coral scientists have started the arduous process of removing tens of thousands of coral fragments from the bleaching threat of warm water and housing them in either land-based coral nurseries or Florida-based aquariums until the water in the Keys gets back to safe temperatures.

“We’ve had bleaching events in the past,” said Keri O'Neil, director of the Florida Aquarium’s Coral Conservation Program. “This is the first time that I’ve seen this primary reaction of, ‘Let’s move them into aquariums because of a bleaching event, because of a high water temperature event.’

“I think we built a lot of trust with that stony coral tissue loss disease rescue project,” she added “Now the coral rescue community and the management community in NOAA Fisheries and FWC are actually confident in the ability of aquariums to keep these corals alive and happy through this potentially catastrophic summer.”

Those corals must be stored in biosecure tanks – separate from organisms that originate outside of Florida – so they can be returned to the ocean someday, O’Neil said.

Corals recovered from the keys are quarantined for 45 days to confirm their health, before they will be introduced into their temporary aquarium homes.

In the case of Florida Aquarium, corals rescued from the Keys will be specimens that expand the genetic diversity of the conservation program’s brood stock.

Coral fostered at other facilities, such as the Reef Institute in West Palm Beach, the Florida Coral Rescue Center in Orlando, Mote Aquaculture Park and facilities at the University of Miami and Nova Southeastern University.

“Any suitable aquarium facility on land is going to be holding corals in Florida,” O’Neil noted.

Diversity seen as a key to survival

There’s not enough controlled aquarium space to house all the coral threatened by high temperature, so there is a focus on preserving genetic diversity with an eye toward planting resilient corals in the future.

For example the Coral Restoration Foundation shared a Friday Field Update on July 28 that during the week it saved 417 staghorn and elkhorn corals – including 83 unique genotypes of staghorn and 118 unique genotypes of elkhorn coral – and 484 more corals from other types such as brain, pillar and star coral.

The rescue effort isn’t simply a matter of plucking coral fragments out of off-shore nurseries or existing reefs, tossing them into buckets and hauling them away.

Michael Crosby, president & CEO of Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium, noted that scientists who cataloged everything they put out in the water must also catalog the fragments as part of the retrieval process and transport them in special, temperature controlled containers to begin the cooling down process.

“As part of our genetic management system we have to track and follow every single one of those fragments,” Crosby said. “And we have to handle them very, very delicately because they’re stressed right now.”

Mass rescue effort

Keys Marine Lab, on the Overseas Highway about halfway between Florida City and Key West, has 60 raceways, or tanks holding 240 gallons each, and four research vessels at its disposal, offering one rally point for scientists with a variety of affiliations to work on the rescue effort.

Mote, which opened the 19,000-square-foot Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research and Restoration in May 2017, arguably has the largest single land-based presence in the Keys.

In addition to Mote’s campus, often referred to as the IC2R3, Summeland Key is home to two other sizeable land-based nurseries – one at the Boy Scouts of America Florida National High Adventure Sea Base and the other across the street at Summerland Farms, run by the Plant a Million Corals Foundation, and by Vaughan, who retired as the director of Mote’s IC2R3 in 2018 to start that nonprofit.

In addition to that facility, Mote opened satellite land-based coral nurseries in a partnership with Bud N’ Mary’s Marina in Islamorada and Reefhouse Resort and Marina in Key Largo, Mote has three separate facilities spread along Overseas Highway.

Like other scientists dealing with the rescue effort, Crosby is quick to draw on the Noah’s Ark analogy but he also likens the effort to Operation Dynamo – the evacuation of more than 338,000 British and French soldier from the French port of Dunkirk between May 26 and June 4, 1940 by a flotilla of military and civilian boats, to avoid a likely massacre early in World War II.

“They lost that battle, obviously, but they came back to win the war,” Crosby said. “It’s much the same way in this.”

Mote sent additional research vessels from Sarasota, giving the nonprofit six vessels to ferry scientists out to reef and nursery sites to rescue coral and Crosby called in favors from area marinas and waterfront hotels to host vessels.

Much of that process followed a plan developed by Mote after Hurricane Irma – and expanded for Hurricane Ian – to evacuate all of its coral specimens in the key to Mote Aquaculture Park in Sarasota in the event of another hurricane.

“If we get a major hurricane event, they don’t all fit inside of the IC2R3 anymore, so we have to evacuate them,” Crosby said.

Crosby estimated that between 75 and 100 of Mote’s roughly 300 employees have been engaged in the response.

“To the best of my knowledge I am not aware of any coral evacuation event that has been as large in terms of sheer number of coral evacuated than this event – which in and of itself it’s groundbreaking,” he added.

Building to a resilient future

Mission Iconic Reefs is built in part on the development of corals that can be more resilient in the face of warming oceans, ocean acidification and disease.

In addition to rescuing coral, scientists will monitor coral left out through the summer, to see how the product of previous resiliency efforts fare.

“We pause on the outplanting – we normally would do that” in August, Crosby noted. “But this presents an opportunity, this period of time, to really gain some information about the different genotypes and their resiliency in different habitats because every single reef down there is being hit to varying degrees.”

Ironically, just prior to the mid-July bleaching event, NOAA Fisheries announced more than $910,000 in Ruth Gates Coral Restoration Innovation Grants – targeting new and ongoing projects to “enhance coral resilience and improve the long-term success and efficiency of shallow-water coral reef restoration in a changing climate.”

The Aug. 1 Sturgeon Moon signalled the start of coral spawning season in the Florida Keys, while gene banks such as the one at the Florida Aquarium and Mote’s Aquaculture Park will continue lab-based breeding in search of a resilient coral.

Once resilient corals are identified, the technique of micro-fragmentation, a process that capitalizes on the natural healing process and allows corals to grow more than 25 times faster than normal, can be used to fast-track their growth.

The combination of both those techniques are part of the key to create heat tolerant coral not unlike the type that currently thrives in the Gulf of Aqaba, in the northern tip of the Red Sea.

That coral currently thrives in water hotter than what currently prompts bleaching in the Florida Keys.

“Over geologic time those coral species have adapted their genotypes and have been selected to be able to survive at much higher temperatures than we experience in the Caribbean,” Crosby said then added that Keys coral could adapt too, if water was warming at a natural pace and not a faster timetable prompted by global warming.

“So Mote’s approach with genetic resilience is we’re helping the coral to be able to evolve with those genotypes being dominant in the system so the whole community and reef can survive and self-replicate over time to a new, changed environment.”

Related: Big Red (or his offspring) may one day help scientists restore iconic Florida coral reefs

Also: Caribbean king crabs arrive at Mote Aquaculture Park; seen as key to restoring coral reefs

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Mote Marine, other scientists rally to save Florida Reef Tract coral