Scientists Spot Trippy Waves Rippling Across Earth’s Outer Core

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Scientists have discovered a series of strange magnetic waves that roll across the surface of Earth’s outer core.

These waves occur periodically—about once every seven years—and are thought to be generated by changes in flow of the core’s molten material.

Learning about these strange features could help researchers better understand our planet’s bizarre magnetic field.

Earth’s wily magnetic field is keeping scientists on their toes.

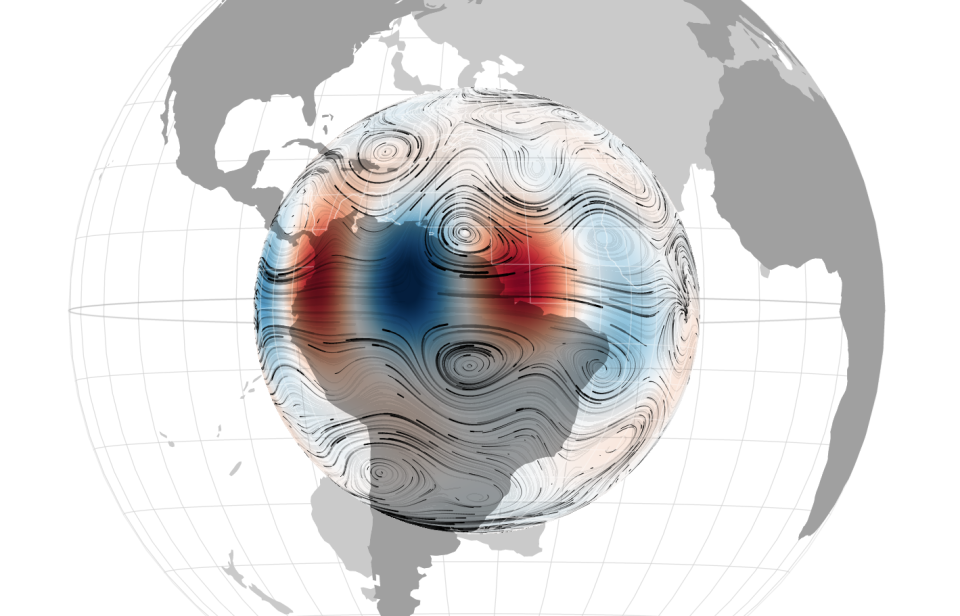

A team of scientists in Belgium and France have discovered a new type of magnetic wave—called a Magneto-Coriolis wave—that courses across the surface of Earth’s outer core every seven years. The researchers analyzed years’ worth of satellite data from magnetic field-scanning satellites to build a model of the bizarre waves.

🌍 You’re obsessed with our weird world. So are we. Let’s unearth its mysteries together.

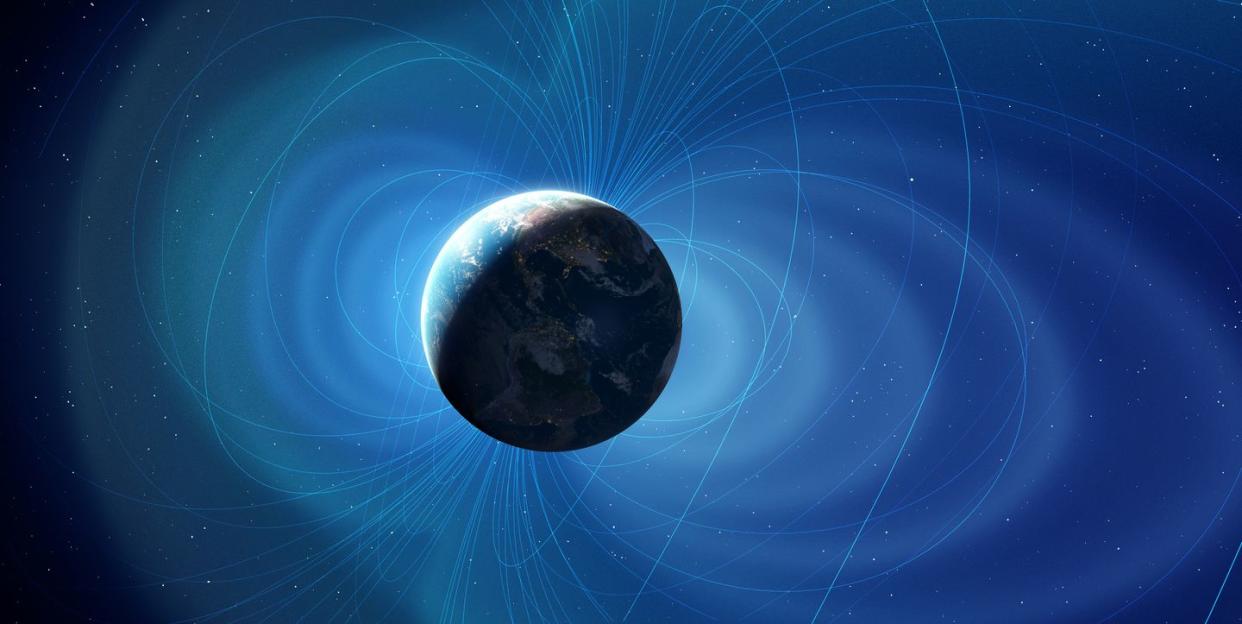

Earth’s magnetic field, also known as the “magnetosphere,” is vital in sustaining life on our planet. This vast bubble of charged particles wraps around our planet like a comet’s tail, protecting us from a barrage of both solar and cosmic radiation. In essence, it has turned Earth into a giant dipole magnet, helping to orient the navigation systems that direct everything from our smartphones to satellites.

Earth’s magnetosphere is generated in our planet’s outer core, a churning sea of molten iron roughly 1,800 feet below the surface. Electrically charged particles in the outer core form convective cells, which produce an electric current that forms what scientists call a “dynamo.” This process is what forms Earth's magnetic field, or magnetosphere.

Our magnetic field is a particularly weird one. It periodically flips, sending the magnetic north pole to the southern hemisphere and vice versa. (Fear not a reasonable amount: The last polar reversal occurred 780,000 years ago. Technically, we are overdue for a pole swap, but experts agree we’d probably be able to adjust.) In recent years—geologically speaking, that is—scientists have noticed other bizarre behavior. The magnetic north pole, for example, is slithering eastward at break-neck speed. And in one region between Africa and South America, the field is even weakening. While understanding these idiosyncrasies has become a priority for many earth scientists, there’s still a lot that we don’t know.

To get a better handle on exactly what the heck is going on with our extremely (!) important (!) magnetosphere, scientists have been sending satellites into Earth’s orbit to study it. The European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Swarm mission in 2013, and the trio of satellites that comprise it have been making important discoveries about Earth’s magnetic field and the innerworkings of our planet ever since. Swarm isn’t the first series of satellites to take on the task, though. Both the German Challenging Minisatellite Payload (CHAMP) mission and the Danish Ørsted mission, which launched in 2000 and 1999, respectively, worked for about a combined 25 years to study Earth’s magnetic field.

This latest research team analyzed and then used years of data collected by these satellites—as well as data from Earth-bound magnetic field detectors—to create a computer model that identified the new type of magnetic wave.

They found that every seven years, these waves sweep westward (at a snail’s pace of 1,500 kilometers per year) across the topmost layer of the outer core, where that boundary meets the mantle. The waves are strongest—or rather, their impact to the magnetic field is the greatest—near the equatorial region of the outer core.

The researchers report a number of factors that may influence the behavior and characteristics of these waves and others like it, including changes in the fluidity and buoyancy of the material in Earth’s core, the rotation of the planet along its axis, and even interactions with magnetic material around Earth. They also believe there could be even more types of magnetic waves yet to be discovered. They published their results earlier this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences.

For years, scientists have suspected these waves might exist, but they weren’t sure when they appeared or for how long they might last. This is the first time they have been observed. While Earth’s surface is covered by a vast array of magnetic field-detecting instruments, it took the satellites’ bird’s-eye view of the Earth and its inner layers to help researchers crack the case.

The more we learn about Earth’s magnetic field, the better we can predict and understand its behavior and processes. “This current research is certainly going to improve the scientific model of the magnetic field within Earth’s outer core. It may also give us new insight into the electrical conductivity of the lowermost part of the mantle and also of Earth’s thermal history,” Ilias Daras, a geodesy and solid earth scientist who works on the Swarm mission, said in an ESA press statement earlier this week.

Studies like these could also teach us about other worlds in our solar system and beyond that have a magnetic field. Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune all have magnetic fields. (Jupiter’s is the largest and most powerful; Mercury’s is the weakest.) Curiously, Jupiter’s moon, Ganymede, also has a magnetosphere—it the only moon in our solar system to possess one—which was discovered in 1996 when the Galileo spacecraft spotted aurorae.

It’s helpful to learn more about this curious feature of our planet, but it’s probably just as useful to accept that there’s not anything we can do about its changes.

You Might Also Like