The Scopes Trial put state in crosshairs of America's culture wars

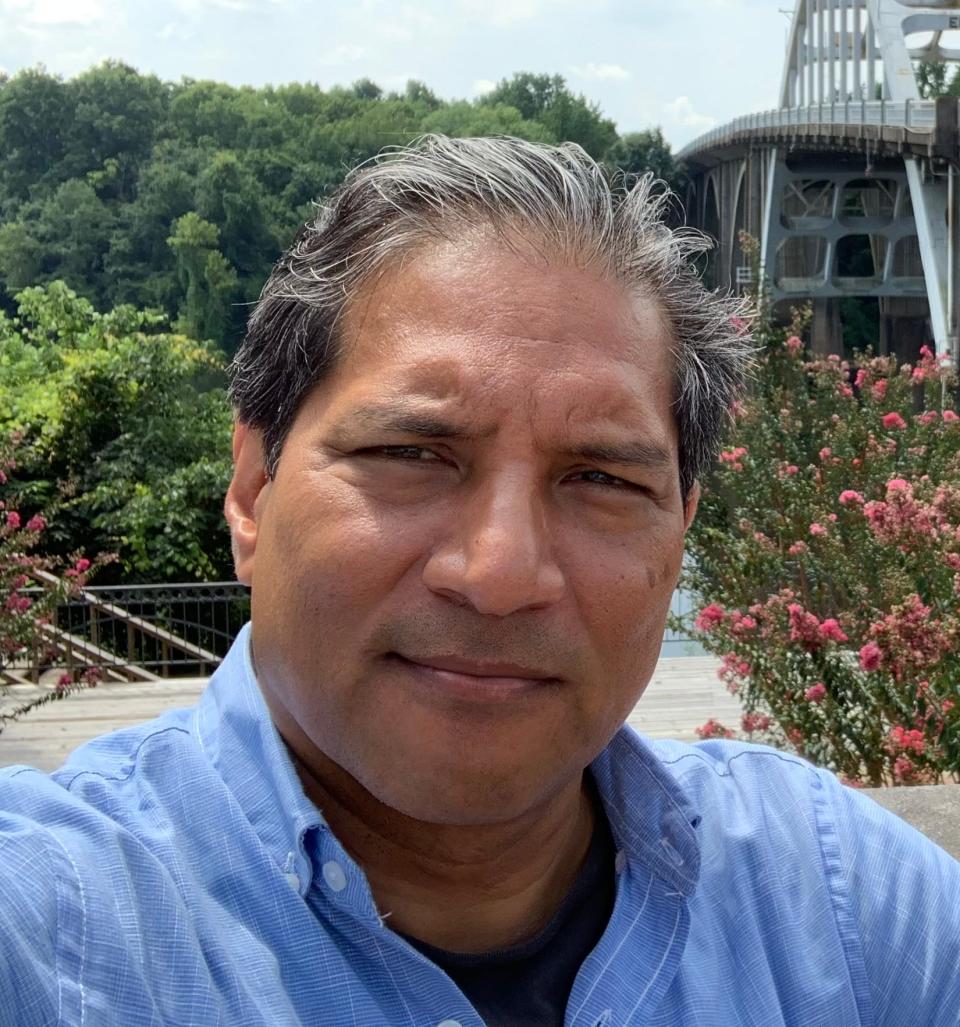

Ram Uppuluri, a good friend, noted in conversation with me that Tennessee had been given national attention before the recent incident in the state legislature leading to expulsion of two representatives. While this most recent incident may not last long in the national spotlight as other things take its place, the one Ram thought of was in the national spotlight for much longer - the Scopes Trial.

Here is Ram’s research on that historical event in Dayton, Tennessee.

***

The effort to expel “the Tennessee Three” from the Tennessee House of Representatives for their unruly demonstration in support of gun safety laws last month was not the first time Tennessee was a flash point in America’s culture wars.

Nearly 100 years ago, in 1925, the nation’s attention was riveted on a small courthouse in Dayton, Tennessee, where two American titans of the law – Clarence Darrow, a labor lawyer from Chicago, and William Jennings Bryan, a former presidential candidate, Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson, and leading Christian crusader – clashed over the teaching of the theory of evolution in public schools.

I would point out that, even though Tennessee was one of a few states that had laws prohibiting the teaching of evolution in public schools, the law was never enforced, and it didn’t prevent the forces of science and technology from marching forward and contributing to cultural change.

Eighteen years after the Scopes Trial in 1925, the frontiers of science were expanded just up the road from Dayton, in Oak Ridge, where physicists built the first graphite reactor and performed the first controlled splitting of the atom after Enrico Fermi’s famous experiment under Stagg Field at the university of Chicago. Scientists and engineers in Oak Ridge went on to produce the uranium 235 needed for "Little Boy," the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare; made fundamental contributions to the development of nuclear power and nuclear medicine; and opened up many new fields of discovery over the years making major contributions world-wide for the betterment of mankind.

Notably, 12 years after Oak Ridge was established, in 1955, the Oak Ridge Public Schools became the first public schools in the state (and the entire Southeast) to desegregate when the Atomic Energy Commission ordered them to do so. This was one year after the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Once again, because of Oak Ridge, the state of Tennessee was the focal point of cultural change in the Southeast and in America.

But in 1925, in the middle of the Roaring 20s, with the American stock market soaring, and new developments in science and technology transforming American life, the state House of Representatives passed House Bill 185, also known as the “Butler Act,” which said:

“That it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any public school of the State to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

The bill effectively banned the teaching of evolution in public schools in Tennessee. It had been introduced by state Rep. John Butler, a farmer representing Macon, Trousdale, and Sumner counties in the Tennessee House. Butler was the head of the World Christian Fundamentals Association (WCFA) , an interdenominational organization which had been founded in 1919 by William Bell Riley, a Baptist minister from the First Baptist Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

In 1919, Riley, addressing 6,000 conservative Christians at the WCFA’s inaugural conference, warned that their Protestant denominations were “rapidly coming under the leadership of the new infidelity, known as ‘modernism.’” (From Summer for the Gods, by Edward J. Larson, Basic Books, New York (2000), p.36)

Riley said that “basic to the many forms of modern infidelity is the philosophy of evolution.” (From Summer for the Gods, by Edward J. Larson, Basic Books, New York (2000), p.37)

Butler, the state representative, stated, "I didn't know anything about evolution ... I'd read in the papers that boys and girls were coming home from school and telling their fathers and mothers that the Bible was all nonsense."

According to Butler:

“In the first place, the Bible is the foundation upon which our American Government is built. ... The evolutionist who denies the Biblical story of creation, as well as other Biblical accounts, cannot be a Christian. ... It goes hand in hand with Modernism, makes Jesus Christ a fakir, (a poor man usually living off alms) robs the Christian of his hope and undermines the foundation of our Government ...”

The Butler Act passed the Tennessee House of Representatives by a vote of 72-1.

It breezed through the state Senate three days later and was immediately signed into law by then Gov. Austin Peay – who is widely regarded as having been a progressive governor of the state, responsible for much of the state’s modernization (ironically). He signed the law into effect to assuage rural voters, he said.

The anti-evolution bill had been a part of a larger campaign, spearheaded by William Jennings Bryan. Bryan believed that the teaching of evolution was a direct threat to the traditional Christian values upon which the country was founded.

Along with Riley’s WCFA, Bryan spoke widely throughout the country in support of a ban on the teaching of evolution, including in Nashville in the years leading up to the passage of the Butler Act.

In New York, leaders of the relatively young American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) were eyeing the Butler Act’s progress through the legislature, and as soon as it was signed into law, issued a statement offering to cover the legal expenses of any teacher in the state who would dare to challenge it.

A Dayton, Tennessee businessman, George Rappleyea, a 31-year-old New Yorker with a doctorate in chemical engineering who worked for a local mining company, convinced the townsfolk of Dayton that the publicity alone from a challenge to the law would put Dayton on the map, attract tourism, and promote growth.

The Dayton group recruited a young, 24-year-old science teacher and part-time football coach, John T. Scopes, and got him to admit that he had been teaching biology from a state-approved textbook that contained a section on human evolution. He became the face of the trial that came to be known as the first Trial of the Century.

The Scopes Trial ran from July 10 to July 21, 1925, at the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton.

It pitted two of the greatest attorneys and statemen of their times against each other – Clarence Darrow, appearing on behalf of Scopes and the ACLU; and William Jennings Bryan, appearing as a special prosecutor to assist the state.

Toward the end of the spectacular trial, it was as though Darrow had put the Christian religion itself on trial when he called his opposing counsel, Bryan, to witness stand as an expert witness. He raised logical questions about the Bible (for example, “How did Noah gather animals from all the continents?”). Bryan was unflappable in his responses and in his proclamations of his deeply held religious convictions.

The exchange between the two titans of the law received national news coverage.

At the end of the trial, the jury came back with a verdict of guilty against Scopes and left it to the judge to decide on the fine.

On appeal, the Tennessee Supreme Court stated in a written opinion that it would have upheld the Butler Act as constitutional under the state and U.S. constitutions, but overturned the fine on a legal technicality: the amount of the fine should have been set by the jury, not the judge.

The State’s Attorney General L.D. Smith immediately announced that he would not seek a retrial.

The Butler Act remained the law in Tennessee until 1967, when the state legislature reacted to the threat of a lawsuit challenging the statute by repealing it.

The following year, in 1968, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Epperson v. Arkansas 393 U.S. 97 (1968) that such bans contravene the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment because their primary purpose is religious.

***

Thank you, Ram.

There you have a short version of the history of the famous Scopes Trial. Can you think of other times when Tennessee has reached national attention for cultural reasons?

How about the early history of the State of Franklin, even before there was a Tennessee. Or how about the Watauga Association government document of 1772, which served as a pattern for the Tennessee constitution and for other such initiatives in other states?

What about the battle of Kings Mountain where Joseph Greer delivered the message of the victory to the Continental Congress in 1780? Or the many Civil War battles in Tennessee … the last state to secede and first to return to the Union?

Or the creation of Oak Ridge in 1942 (not known about until Aug. 6, 1945) and even today the Nuclear Age continues to highlight Oak Ridge with nuclear reactors, nuclear weapons, basic scientific research, and the world’s fastest supercomputer?

Or the desegregation of public school by the "Scarboro 85" in 1955? Or the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King in Memphis? And I am sure you can think of many more.

Tennessee is not unaccustomed to being in the national spotlight.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: The Scopes Trial put state in crosshairs of America's culture wars