How climate change will bring more pests and disease to New England

Last month in Egypt, floods from heavy rain drove swarms of "deathstalker" scorpions from their hideouts and into people's homes. More than 500 people were stung, and some Egyptian scientists began to publicly make connections to climate change, saying they'd never seen such intense flooding touch residential areas.

New England may not have scorpions burrowing in its hills, but it does have insect and arachnid populations that people will begin to see more of due to climate change.

Climate change is causing a rapid decline in some species – such as butterflies and honeybees – while also making the planet more hospitable for others. Across the New England region, warming temperatures, milder winters and periods of increased rainfall make an ideal recipe for an increase in ticks and mosquitoes, experts say. It's also paving the way for new species to move northward.

As these populations expand, the question becomes: will the risk for the infectious diseases they carry – such as Lyme disease, babesiosis, the West Nile and Eastern equine encephalitis viruses – increase, too?

Both the Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledge studies pointing to climate change as contributing to the extended range of ticks, increasing the potential risk of Lyme disease, and accelerating mosquito development and biting rates.

"The more water and more heat that we get, the more available mosquitoes there are to carry all of these viruses," said Todd Duval, entomologist for the Bristol County Mosquito Control Project in Massachusetts. "Everything that helps these animals survive and thrive, which is warmer winters, that helps the diseases perpetuate."

What is changing?: Cicadas have existed for more than 5 million years. Now, humans threaten their future.

More: Summer of extreme weather reveals stunning shift in the way rain falls in America

Climate change is among a handful of factors affecting vector-borne disease transmission, according to a recent study by Rhode Island researchers on tick-borne diseases and climate change. Other environmental and socioeconomic factors, like housing development and population growth, complicate "direct predictions of climate change effects on future disease distribution patterns," the study said.

Tick expert Dr. Sam Telford, professor of infectious diseases and global health at Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Health, said he doesn't see the epidemiological evidence yet, noting "it could go either way."

Besides the familiar pests, New Englanders may begin to see insects they've never come across before, like the southern pine beetle. Native to forests in the southern U.S., the beetle, which is the most destructive and deadly insect to pine trees, has crept its way north amid the warming climate.

"They can kill hundreds of thousands of acres a summer," said Claire Rutledge, an entomologist with the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station.

A 2017 study by climatologists at Columbia University said approximately 40,000 square miles of pitch pine forests spanning from eastern Ohio to southern Maine will become hospitable to the beetle by midcentury. And by 2080, those conditions could extend into Ontario and Quebec.

'Unprecedented' outbreak: Armyworms are destroying lawns across the US, often overnight

Ticks like humidity, precipitation, mild winters

Larry Dapsis, deer tick project coordinator and entomologist for the Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, said his phone "rings way more than it used to."

As New England trends towards milder winters, that's good news for ticks and bad news for humans. The warmer temperatures mean fewer disease-carrying ticks will die off, ultimately leading to an increase in overall tick population.

Dapsis tells people that tick season is 365 days a year now. Weather and temperature trends will determine if ticks become more active during atypical times.

"Ticks actually make a chemical called glycerol, which is anti-freeze," said Dapsis. "They are a perfectly engineered little package, so when it gets really, really cold, they just hunker down. And when it gets up above freezing, they're up and active."

More: It's still prime season on Cape Cod for ticks and the diseases they carry

Ticks in the nymph stage, Dapsis said, account for 85% of tick-borne diseases, and it's anticipated that they'll begin to emerge earlier in the spring because of warmer temperatures. Nymphs typically show up in mid to late May, he said.

Climate change has also introduced new tick species to New England.

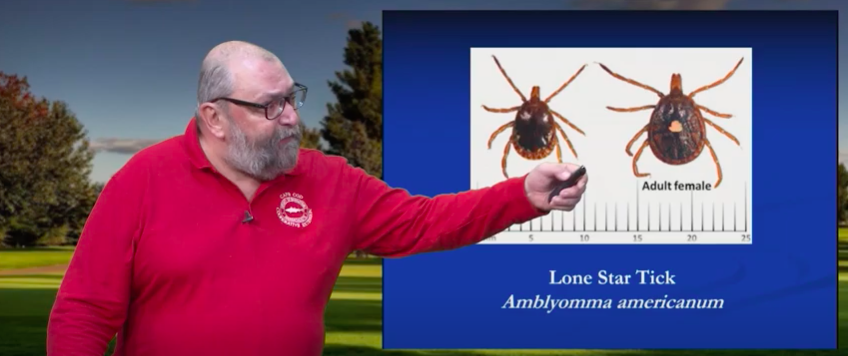

"Ecologists say, 'You want a sign of climate change? Let's look at the Lone Star tick,'" said Dapsis. "The Lone Star tick has been moving northward steadily for years. Between climate change and migratory birds, now it's the third tick in our landscape of public health importance."

The Asian longhorned tick, an invasive species first identified in the U.S. in 2017, is "on our doorstep," he said. It's since been found in Connecticut and Rhode Island, as well as a handful of other states.

Cases of Lyme disease, transmitted primarily by deer ticks, have doubled in the U.S. over the past two decades, but reporting techniques vary and don't take into account factors like population growth and development.

EPA data shows among the states where the disease is most common and where cases have been tracked consistently from 1991–2018, Maine and Vermont have experienced the largest increases in reported case rates, followed by New Hampshire. The data, however, is missing numbers from Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, because the states have changed their reporting methods, making it difficult to calculate an accurate trend, the EPA said.

![Tick signage outside a rail trail in West Boylston, Massachusetts. [T&G Staff/Christine Peterson]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/bVM20TBsK_IgmjtZSKUDFw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcxNQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-providence-journal/03af88fb43c4f540c321b14647ed2e74)

More: Potatoes that could survive climate change? Researchers try producing crop amid warming temperatures

On the other side of the coin, Tufts University's Telford, who has long been on a crusade against Lyme disease, thinks climate change could result in New England becoming more like its southern neighbors, where south of Virginia, Lyme is fairly rare. The Lone Star tick doesn't carry Lyme, and as the species has moved north, in places like Long Island, New York, it's begun to dominate the deer tick population.

"The Lone Star tick is not as much of a vector as deer ticks are," Telford said. "But there's no question that people are now suffering in southern New England and the islands because the Lone Star tick has invaded. It is much more of a pest situation."

People bitten by Lone Star ticks can develop a circular "STARI" rash, followed by fatigue, headache, fever and muscle pains. They are often treated with oral antibiotics. A Lone Star bite can also trigger a potential allergy to red meat.

On Cape Cod, Dapsis is all about prevention and public messaging. His work with Barnstable County has been recognized widely, and as the tick situation continues to morph, he offers some guidance.

"We're going to see our exposure risks increase, and that's why our prevention message is front and center," he said. "We're not building a space station here. There are some simple things (we can do). We're in a tick-friendly environment that is becoming more tick-friendly. Don't be tick afraid, but be tick aware."

'It was our largest mosquito season'

A 2019 study published in Nature Microbiology by an international team of researchers showed that climate change will expose half of the world's population to disease-spreading mosquitoes by 2050.

Like ticks, warmer temperatures are helping mosquitoes survive. Duval, of the Bristol County Mosquito Project, said mosquito larvae tend to hang out in white cedar swamps and cavities of trees during the wintertime, sheltering from the cold.

"Mild winters are good for them," he said. "We're not getting these freezing winters that tend to keep everything in check."

What does data tell us about our state?: Our warming climate is having a dramatic impact on precipitation.

What's interesting about mosquitoes, and in particular the diseases they carry, Duval noted, is that they'll benefit from two climate extremes – both drought and increased precipitation. And in New England, climatologists say the region is expected to see more dry spells punctuated by shorter deluges of precipitation, as demonstrated this past summer.

During droughts, birds are pushed to sources of water, and where mosquitoes breed. Being in close quarters with birds means mosquitoes are more likely to contract West Nile and EEE from them, as they congregate in one place.

On the other hand, Duval said, lots of rain usually results in a "huge, huge flush of brand new mosquitoes."

"This season was about two weeks longer than it usually is, and it was also our largest mosquito season, largely attributed to the two hurricanes that came through," he said. "All of that helps to prime the mosquito habitats. The floodplains and woodland pools and our swamps."

In Rhode Island, for example, the state saw five of its 10 wettest years in history in the past two decades. In 2019, it was part of a deadly EEE outbreak in southern New England, with cases also in Massachusetts and Connecticut. At the time, scientists said it was difficult to draw conclusions between the spread of EEE and climate change. It is conceivable, though, they said, that temperature changes and increased rainfall could lead to more outbreaks. They also pointed to related factors such as more development encroaching on wetlands.

Southern pine beetles have made their way to New England

In 2015, scientists first discovered that the beetle most deadly for pine trees had found its way to southern New England, specifically Connecticut. It appeared as though the insects had "just rained down out of the sky," said state entomologist Rutledge.

"It was very surprising to find them," she said.

Nearly seven years later, the beetle has been tracked all across Connecticut, in Rhode Island and on Cape Cod. Rutledge said scientists are seeing "larger and larger numbers" each year, a trend that's likely to continue as long as global warming persists and milder winters become a norm.

"The critical thing for (the beetles) is the minimum winter temperature, and we need the temperature to be minus-13 Fahrenheit for at least a couple nights (to keep populations in check)," she said. "We just have not been doing that on a regular basis in Connecticut."

A polar vortex during the 2015-2016 winter likely helped stifle the population growing in New England, Rutledge said, but there haven't been winters like that since.

As a result, southern pine beetles could ultimately go from an "endemic" – where they solely attack weak trees – to an "epidemic," where the population builds up enough to initiate "mass attacks," Rutledge said, and overwhelm a healthy tree's defense system.

Female southern pine beetles find host trees and begin chewing their way beneath the bark while releasing pheromones to attract others to the area. Ultimately, trees can die from fungal infections as a result of the beetles' feeding.

"When you have a lot of beetles attacking a tree, you get tree mortality within six months," said Rutledge.

Of particular worry are New England's pitch pine trees, a "favored host" to southern pine beetles. The region's pitch pine barrens are "really at risk," Rutledge said, if the beetles are able to flip to an epidemic stage.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: More ticks, mosquitoes, southern pine beetles due to climate change