Scott Sauls envisioned Christ Presbyterian as a city on a hill. Why it didn't last

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A half dozen Christ Presbyterian Church staff secretly circulated a book.

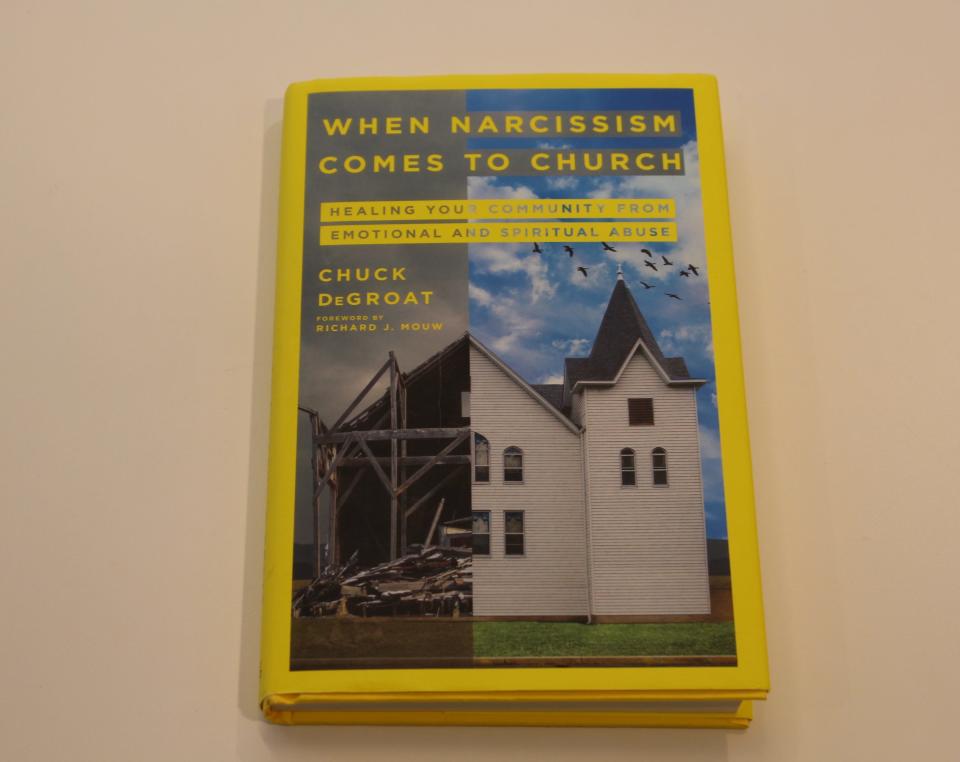

This subversive text — “When Narcissism Comes to Church” by Chuck DeGroat, published in March 2020 — awakened the megachurch's employees to their shared grievance working under senior pastor Rev. Scott Sauls.

“Many narcissistic pastors have little ability to empower others in meaningful ways,” DeGroat said in his book. “They’re often better at imagining and starting new projects rather than sustaining them.”

DeGroat’s descriptions matched Sauls’ behavior that employees observed, such as his hypervigilance about projects that typically brought Christ Presbyterian acclaim while neglecting people and priorities outside that orbit. He would get angry about how music worship sounded, for example, and if he wasn’t enraged, would more passively show disapproval with gestures of discomfort.

The covert book club of Christ Presbyterian staff realized they weren’t crazy nor alone. DeGroat’s book showed them experiences they once chalked up as coincidence or one-off oddities were symptomatic of a narcissistic pattern.

It eventually caught up with Sauls, who resigned two weeks ago after a six-month disciplinary hiatus. But many former employees feel the public remains largely unaware of their hardships and the role of other Christ Presbyterian leaders in that story.

Not long after DeGroat’s book alerted staff to their situation, a new executive director stepped in and gave them more reason to worry. Under the new executive director, Doug Korn, who oversees staff and served as Sauls’ deputy, employees were less insulated from Sauls’ insular and unpredictable management.

“It went from a church to a private equity firm overnight,” one former employee said in an interview. “Jesus and loving people disappeared. The only people to be loved were Scott Sauls and Doug Korn.”

Under Sauls’ leadership, Christ Presbyterian grew its footprint throughout the region and distinguished itself for preaching hospitality amid debate over exclusionary measures within the church’s conservative denomination, the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Sauls explicitly led in the footsteps of his former boss and mentor, the late Rev. Tim Keller, whose revered legacy within evangelical Christianity augmented Christ Presbyterian’s prestige as a city on a hill.

But the entire time Sauls also struggled with insecurity and sharing control, taxing staff culture and undermining some of the very successes that earned him and Christ Presbyterian acclaim. Partnerships severed and ministries shifted focus; staff left demoralized about a system of oversight that didn’t intervene early enough or at all.

Eight former Christ Presbyterian employees spoke with or shared records with The Tennessean about the circumstances surrounding their departure. The former staff requested anonymity citing fear of retaliation. Some signed non-disparagement agreements with Christ Presbyterian.

Christ Presbyterian declined to comment for this story. Sauls, who previously addressed leadership issues in a video in May, did not respond to a request for comment.

Staff who spoke with The Tennessean, and others who declined, expressed exhaustion at reliving painful experiences as they try to rebuild a sense of purposeful work. That pursuit of a deeper vocation is what initially led them to Christ Presbyterian, for which some left their home churches or jobs at private companies. But what they encountered was a cruel reversal.

“It was such a sense of betrayal,” a former employee said in an interview. “Because this is communicated to you in a way, whether it’s intended or not, that God is rejecting you, the church is rejecting you. It was a crisis of faith for me.”

Success and suspicion

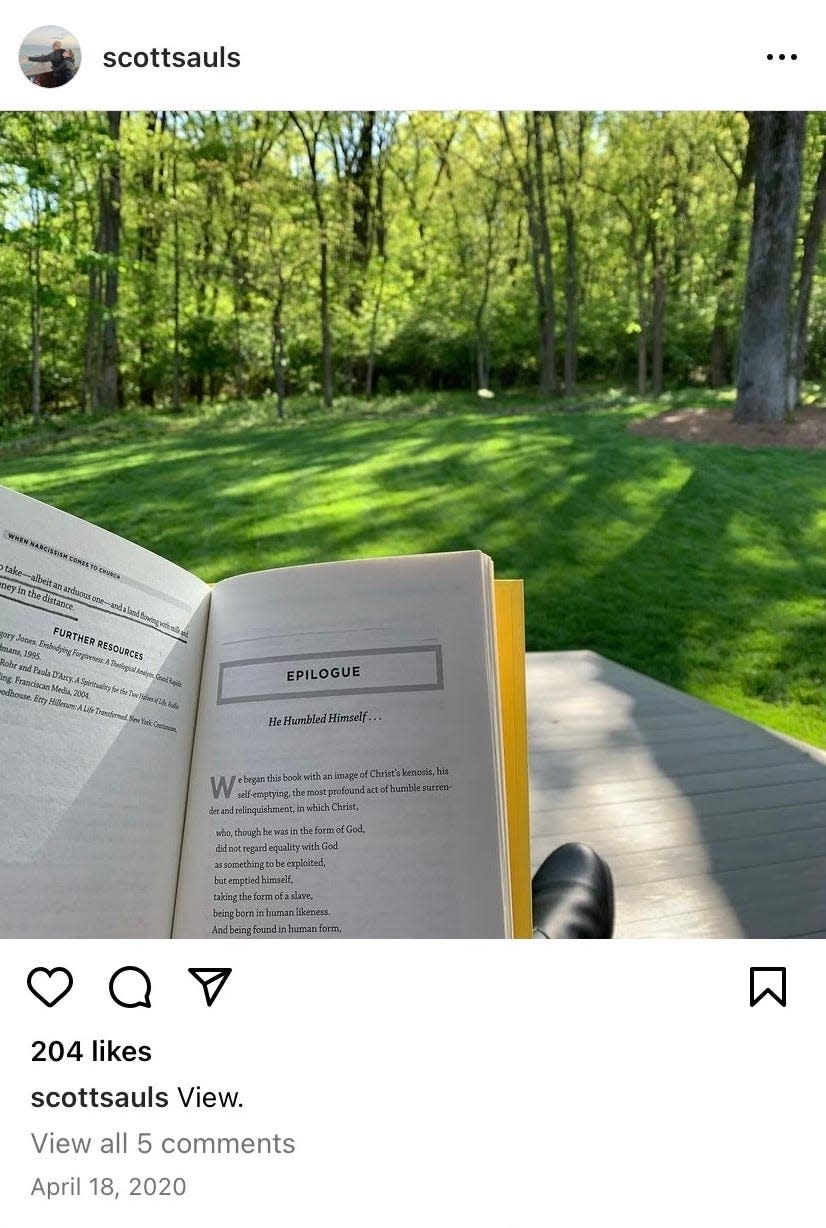

As the covert book club of Christ Presbyterian staff discreetly read DeGroat’s book, their boss did the same out in the open.

Sauls posted on Instagram in April 2020 a photo of “When Narcissism Comes to Church” laid across his lap as he sat on his back porch with his legs outstretched. The caption was just as chill as his pose: “View.”

But the view among the covert book club was of increasing discomfort the more they read.

“In ministry, pastors use their congregations to validate a sense of identity and worth,” DeGroat said in the book. “The church becomes an extension of the narcissistic ego, and its ups and downs lead to seasons of ego inflation and ego deflation for the pastor.”

At the time, Christ Presbyterian, in addition to its flagship campus on Old Hickory Boulevard at the Nashville/Brentwood line, had two satellite campuses — on Music Row and in Cool Springs — and would soon launch a third, Koinonia. It also created the Nashville Institute for Faith and Work, a ministry that teaches a curriculum to cohorts of fellows on applying ones’ faith to their daily lives.

Sauls authored five of ultimately six books, published hundreds of blogs, and was gaining a social media following that’s now half a million-plus. His social network grew to include politicians, music stars, and leading figures in the PCA and other Christian groups.

“For reasons beyond my ability to understand, God has graciously protected me from moral collapse over the years,” Sauls said in a May 2020 blog, published just a month after he posted on Instagram about reading DeGroat’s book. “Knowing the fragility and fickleness of my own heart, sometimes I marvel at how this could be the case.”

Sauls’ blog, titled “On the Rise and Fall of Pastors,” acknowledged pressures facing pastors like himself and a susceptibility to respond in a way that’s “defensive, snippy, controlling and even aggressive.” He urged congregants against placing pastors “on a pedestal.”

As was his tendency in writings, Sauls pointed out the pitfalls for ministry leaders in similar contexts yet stopped short of identifying its prevalence within his own organization. Christ Presbyterian staff understood Sauls’ vulnerability to be what DeGroat called “fauxnerability.”

“Narcissistic systems exist for themselves, even though their mission statements and theological beliefs may be filled with the language of service, selflessness, justice, and care,” DeGroat said in his book. “Those within the system find this contradiction exhausting.”

Strategy and spirit

Sauls led Christ Presbyterian with a business strategy and spirit he envisioned after Tim Keller, whom Sauls worked under as an associate-level pastor.

“He wanted to be the next Tim Keller,” a former Christ Presbyterian staff said in an interview.

Keller, who died in May, founded Redeemer Presbyterian Church, now a five-campus congregation, and Redeemer City to City, a church planting nonprofit. Redeemer Church also launched the Center for Faith and Work, which was the basis for Christ Presbyterian’s institute for faith and work.

When Sauls bid for the top job at Christ Presbyterian in 2012, Keller himself predicted how Sauls’ four-plus years at Redeemer Church would translate.

“You can trust him (Sauls) because on the one hand, he’s learned our best practices and developed his own skills as he’s grown here,” Keller said in a video to a Christ Presbyterian pastoral search team, endorsing Sauls’ candidacy for Christ Presbyterian senior pastor. “He’s an entrepreneur. He is terrific in creative innovation, and he loves to get new things started.”

In addition to his ministry success, Keller is widely celebrated for his ethics and the biblical basis from which he derived his views and approach to dialogue. In the PCA, Keller championed a big tent vision that Sauls and others coalesced behind as an alternative to increasing factionalism in the denomination.

In turn, Sauls urged people to bridge partisan divides and pray for all political leaders, a message he promoted despite Christ Presbyterian’s connections with Republican politicians. U.S. Sen. Marsha Blackburn, one of Tennessee’s most polarizing elected officials, is a longtime Christ Presbyterian member.

Sauls developed a public persona that defended a traditionalist worldview that was also socially and culturally cognizant.

“The more we walk the narrow path, the wider our embrace will be,” Sauls said in a December 2018 blog. “When love is in the air, divisions and factions fade. When love is in the air, we are moved, even compelled, to expand our ‘us.’”

Christ Presbyterian began appointing deaconesses, elevating women to higher leadership roles within the bounds of PCA policy. The PCA is a complementarian denomination, meaning it believes men and women have certain assigned roles. As a result, the PCA doesn't ordain women as pastors (called "teaching elders") or ruling elders, who are lay leaders.

Sauls showed support for Revoice, a conference for people who identify as same-sex attracted and are celibate. A firestorm in the PCA over Revoice precipitated proposed policy changes and a measure to affirm the Nashville Statement, a 2017 declaration against LGBTQ rights. Sauls was among the minority who opposed those proposals.

A more conservative camp in the PCA accused Sauls of teaching “false doctrine” and rendering the denomination vulnerable to “liberalism.” Sauls seemed to welcome the opportunity to fight back against his critics whom he considered legalistic “Pharisees.”

“How many people do you know who started following Jesus because someone scolded them, Sauls said in a November 2020 blog. “If people are going to resist and reject us, let’s at least make sure that they are the same kinds of people who resisted and rejected Jesus.”

Sauls’ advocacy shaped Christ Presbyterian’s identity, and the church’s missional priorities grew interdependent with its senior pastor’s views.

“We will celebrate our diversity — opening our lives and hearts and homes to sinners and saints, doubters and believers, seekers and skeptics, prodigals and Pharisees,” Christ Presbyterian said in a revised mission statement it adopted in August 2016, according to Sauls’ blog. “We will commit our resources to train, equip, and resource Christians for the integration of faith and work.”

The Nashville Institute for Faith and Work, among other ministries, was favored as an embodiment of that mission. Founding director Missy Wallace led the institute in a “city-facing” direction, serving participants from Christ Presbyterian and from other local churches.

Bearing a similar burden, Koinonia launched in Nashville’s majority Black neighborhood of Bordeaux specifically to reach a more diverse population. Christ Presbyterian planted its third satellite campus under the leadership of the Rev. Mika Edmondson, the first Black pastor ordained by the Nashville Presbytery — the regional authority for churches in Middle Tennessee affiliated with the PCA.

For Sauls and Christ Presbyterian, Koinonia also demonstrated their responsiveness to racial injustice.

Sauls said in an October 2020 blog mentioning Koinonia’s launch, “If you are a person of color, thank you for your patience as we, your brothers and sisters, endeavor imperfectly, but sincerely, to see and love you better.”

Setbacks and staff turnover

Less than two years later, Sauls recorded a video to share some disappointing news with Christ Presbyterian: Koinonia was splitting off.

“Of course, this was not the original plan,” Sauls said in a July 2022 video, which also featured Edmondson. “The only thing God can do with our plans is improve on them.”

Christ Presbyterian’s hierarchy and relationship with its satellite locations — Sauls was at the top, after him was the executive director, and then satellite campus pastors and other leaders — presented challenges for Koinonia.

Edmondson didn’t share every detail but said in the July 2022 video Koinonia sought independence to “fully own the governance of our own affairs and to be sufficiently flexible to minister in our unique context.”

Edmondson declined to share additional details in response to a request for comment.

News of Koinonia’s independence was one of the first public signs of Sauls’ success facing hurdles. But behind the scenes, that fraying had been happening a lot.

Mass turnover starting mid-2021 affected entire departments such as the Nashville Institute for Faith and Work, church communications, youth and children's ministries, worship, congregational care, and missional living. Many of those departments lost director-level staff.

Most of the staff officially resigned, though some did so after learning the church would likely fire them, according to interviews with former employees. At least four signed separation agreements with a non-disparagement clause in exchange for severance.

But even those who didn’t leave under pressure felt they had little to no choices.

“The health of the organization simply needs to be prioritized,” said a former employee in a 2021 resignation letter, according to a copy The Tennessean obtained. “I in good conscience cannot work for the church going forward.”

At least 44 Christ Presbyterian staff left between 2016-2022, 40% of whom specifically departed in 2021 or 2022, according to a list The Tennessean obtained containing former employees’ names and verified using LinkedIn, Facebook or directly communicating with former staff. Nearly half of those 44 former staff were pastors or director-level staff.

Signs and secrets

Signs of a systemic problem were long present before it pushed people out.

“I was really surprised by the culture and staff behavior. It was competitive and unprofessional,” a former employee said in an interview about their observations as early as 2016. “People were very stressed out and overworked, they didn’t trust each other, and very adverse to change.”

There was a “golden child” phenomenon in which Sauls invested far more energy and time into projects he prioritized and the staff overseeing those projects. Meanwhile, he was removed from other departments not working on those projects. Some of his top priorities included the Nashville Institute for Faith and Work, worship music, and Koinonia.

The church’s public-facing features, from its online presence to its worship music, captured Sauls’ attention more often. A few times, church staff worked on Sauls’ personal website (which Christ Presbyterian linked to at the top of its website) or promotional material for his books. The church sold Sauls’ books in the lobby a few times and, in one instance, purchased copies as part of an Easter service invitation to families whose children attend Christ Presbyterian Academy, which is the church’s K-12 school.

But to former staff, Sauls isn’t singlehandedly responsible. They said other Christ Presbyterian leaders went with the status quo or sometimes added to the tension, a phenomenon that DeGroat described as common.

“Churches are particularly susceptible to a phenomenon called ‘collective narcissism,’ in which the charismatic leader/follower relationship is understood,” DeGroat wrote in “When Narcissism Comes to Church.” “The leader relies on the adoration and respect of his followers; the follower is attracted to the omnipotence and charisma of the leader.”

Sauls struggled to balance priorities and communicate with staff, especially those who managed lower priorities. The transition in executive director exacerbated that unhealthy cycle.

Former executive director Bob Bradshaw, who served as Sauls’ deputy for 8.5 years, retired in January 2021 and soon after became CEO of a church consulting firm called McGowan Global Institute. Bradshaw’s successor, Doug Korn, fully transitioned into the executive director role by April 2021 following a career as a corporate executive for Mars Petcare North America and Animal Biosciences Inc.

“Those few months were pretty jarring,” said a former employee in an interview. “He (Korn) came in and changed everything right out of the gate.”

Korn was especially focused on reducing church spending, confounding staff who understood the church to have a healthy cash balance and yearly revenue. Also, Korn communicated proposals aimed at reducing spending in adversarial ways or with little room for input.

“It seems ministry decisions are being made in isolation without input from those closest to the work of the ministry,” said a former employee in a 2021 email to the church’s HR director, according to a copy The Tennessean obtained from that employee. “It appears to be secretive and all the closed-door conversations will contribute to a culture of fear.”

Korn told the Nashville Institute for Faith and Work he was pulling back spending, including by cutting staff. Institute staff sought to address Korn’s concerns while Christ Presbyterian’s eldership deliberated changes to the ministry. Institute staff felt those deliberations diminished their perspective or excluded them altogether.

The institute had stood out for its history of women on staff at a church in which men run most else. But that sense of empowerment among the women on the institute’s staff faded during those 2021 deliberations.

“This time, I was totally left out,” said one of those former employees in an interview. “I was not at the table.”

A sanctuary divided, singing united

The unilateral decision-making by select Christ Presbyterian leaders was a recurring barrier for staff and, more recently, for congregants, too.

Staff began calling for a third-party review three years ago, a request that Christ Presbyterian elders rebuffed several times until eventually deciding to invite the Nashville Presbytery to conduct its own inquiry. That inquiry led to Sauls’ discipline in May but has also left questions about transparency and propriety.

A renewed push for a third-party review led by a group of deaconesses finally received elder approval last month. The church is currently deciding on a firm to hire.

“This is not all about Scott," pastor David Filson said at a Nov. 12 congregational meeting. "There have been issues we have all discovered in leadership here.”

Unlike congregationalist denominations that believe in autonomous local churches, such as the Southern Baptist Convention, the PCA’s system of church elders and presbyteries is more rigid and designed to ensure greater accountability.

But to Christ Presbyterian’s former staff and its congregants, that same system has aided the circumvention of responsibility.

Congregants said at the Nov. 12 meeting they have felt “in the dark” and “like the church was a ship without a rudder.” Many shared during a Q&A portion of the meeting that they knew few details as to why Sauls was resigning and thus, were reluctant to vote to accept the resignation.

Some of the same congregants who joined a standing ovation for Sauls later clapped for congregant Nina Woodard after she spoke publicly and accused Sauls of “lying” and the church’s leadership of denying membership its ability to make informed decisions.

"To anyone who has been hurt, whether known or unknown to me, I am deeply sorry," Sauls said at the Nov. 12 meeting. "I make no excuses and I ask for your forgiveness.”

Some congregants were on the edge of their pews while others cried, overwhelmed with confusion or a sense of betrayal. Tension in the sanctuary was palpable.

Yet the group voted overwhelmingly to accept Sauls’ resignation and closed the meeting by singing the doxology.

“Praise God from whom all blessings flow, Praise Him, all creatures here below…”

Despite the assembly’s dissonance for the past hour, they sang in perfect harmony.

Liam Adams covers religion for The Tennessean. Reach him at ladams@tennessean.com or on social media @liamsadams.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Scott Sauls: Ex-church employees detail volatility, narcissism