SCOTUS Considers Reining in One of This Country’s Worst Police Abuses

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

How easy should it be for cops to seize your property, for months on end, for no real reason other than that “they know they can get away with it”—even though you haven’t been convicted or even accused of a crime?

This term, the Supreme Court will be considering this question—and, much as I can’t believe it, at least one of the justices seems to think that it has a complicated answer.

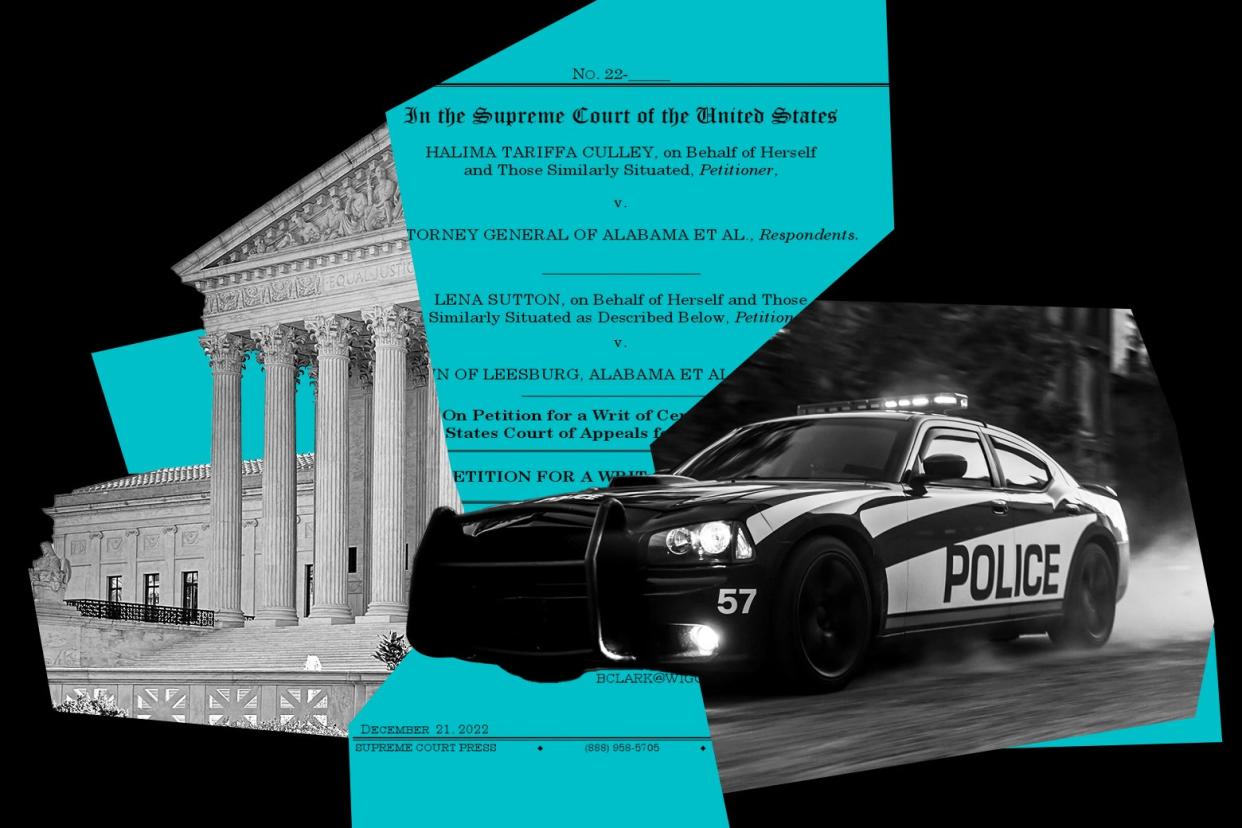

On Monday, the court heard oral argument in Culley v. Marshall, a case that began winding its way to the court several years ago, after police in Alabama pulled over Halima Culley’s son in a car she’d bought for him to use while he was away at college. They arrested him after finding marijuana inside, and he later pleaded guilty to a minor drug offense. That same month, Lena Sutton lost her car, which she’d lent to a friend after police (also in Alabama) found drugs during a routine traffic stop.

Neither Sutton nor Culley was present when police pulled their cars over, let alone charged with anything. But when they asked for their cars back, police were having none of it. Instead, the state initiated a process known as civil asset forfeiture, which allows police to seize—and keep—property allegedly involved in a crime. By one estimate, states and the federal government have used civil asset forfeiture to rake in at least $68.8 billion since 2000. In Alabama and 24 other U.S. states, 100 percent of the proceeds go to funds controlled by law enforcement agencies, many of which depend heavily on the spoils to pad their budgets. Forfeiture often magnifies the cartoonish abuses of power for which police in this country are already infamous: For example, a sheriff in Camden County, Georgia, bought so many boats with seized assets that locals said he was running a Camden County Navy.

In theory, civil asset forfeiture is a tool for depriving scary street gangs and wealthy drug kingpins of the means to keep plying their deadly trades. In practice, it amounts to legalized extortion or even outright theft, and empowers armed state agents to line their pockets at the expense of legally innocent people who have no meaningful recourse.

Alabama’s forfeiture scheme includes protections for innocent owners, and eventually, courts returned Sutton’s and Culley’s cars after determining that they were, in fact, unaware of what their friends and family were doing. A simple hearing would have established this fact in roughly five minutes. But at the time in Alabama, the only way for people like Sutton and Culley to get their property back while their cases were pending was to put up a bond of twice the property’s value. And thanks to congested civil dockets, forfeiture actions can drag on for months or even years. As a result, Sutton—who, like most people, did not have two cars’ worth of spare cash on hand—went without a car for 14 months, rendering her unable to find work or make her medical appointments.

It is important to understand that Sutton and Culley are not asking the Supreme Court to do what a Supreme Court in a functioning society would do: plunge the institution of civil asset forfeiture into the depths of jurisprudential hell. They are simply arguing that the government should have afforded them a hearing to determine whether impounding their cars was necessary, so that they could have retained the ability to, say, drive to the grocery store for the year-plus that the legal system took to sort out their cases.

At oral argument, the justices spent most of their time debating which standard courts should use to determine whether people have a fair opportunity to get their stuff back: one standard, borrowed from a Supreme Court case called Barker v. Wingo, which applies to the Sixth Amendment right to a speedy criminal trial; or another, from Mathews v. Eldridge, which is about what the due process clause requires the government to do before denying someone some sort of government benefit.

This is, even by appellate litigation standards, pretty dry stuff. But this case could have life-changing consequences for victims of civil asset forfeiture, who are often among the most vulnerable people in America. Because cars are among most people’s most valuable assets, in both financial and practical terms, vehicle seizures are devastating for those who depend on reliable transportation to earn a living, go to school, or—especially relevant here—make court dates. An amicus brief filed by the New York–based Legal Aid Society recounts how, before a 2002 federal appeals court decision required the city to overhaul its procedures, residents faced yearslong delays in getting their impounded cars returned. Some were desperate enough to buy their cars back; those who couldn’t afford it were forced to abandon their cars altogether.

And given the narrowness of the technical question in this case, the justices were surprisingly critical of civil asset forfeiture in general. Their questions on Monday suggest that if police are going to have this dubious power, the least the federal judiciary can do is set some modest boundaries on it.

“We know there are abuses of the forfeiture system. We know it because it’s been documented throughout the country, repeatedly,” said Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Without procedural safeguards in place, she suggested, “what we’re basically saying is, ‘Go at it, states: Take as much property as you want; keep it as long as you want. Let’s hold out no hope whatsoever that there’s ever going to be any further process that’s due.’ ” Given that the timeline for resolving forfeiture cases can be a year or more, Sotomayor said, “I don’t consider that timely if I’m an innocent owner who relies on my car for survival.”

Other justices were similarly skeptical about empowering the state that wants your money to make the rules about when and how and how long they can hold on to it. Justice Neil Gorsuch, whose selective libertarian sympathies occasionally come into play in matters like this one, voiced concerns about “kangaroo courts” governed by “processes that are deeply unfair, and obviously so, in order to retain the property for the coffers of the state.” In light of the “incentives operating on law enforcement officers that tend toward those abuses,” asked Justice Elena Kagan, if requiring a “really quick” hearing would level the playing field a tiny bit, “why shouldn’t we do that?”

Other panelists were less sympathetic. Justice Samuel Alito, perhaps the court’s most prolific cop enthusiast, expressed great concern about the prospect of making police officers do actual work. “How is it practical to expect the police to be able to prove within a short period of time that the owner of the car did not know that the person driving the car was going to have drugs in the car?” he asked. Alito also insinuated that people might lie at retention hearings—kind of a silly point, given that, as Culley’s counsel noted, non-innocent owners facing parallel criminal prosecutions would have precious little incentive to show up and commit perjury, potentially landing themselves in prison for even longer.

Police, meanwhile, have every incentive to initiate forfeiture proceedings as often and as slowly as possible. As Gorsuch highlighted on Monday, the government often uses fear and uncertainty to pressure people into unconscionable settlements that amount to hefty ransoms. In 2012, for example, police in Virginia took $17,550 from Mandrel Stuart, a Black restaurant owner pulled over for a traffic violation. The state offered to return half the money—his money—which is an offer to “settle” in the same way that the Mafia’s offer to “protect” your storefront is part of a bona fide foray into the loss prevention industry. Stuart rejected the offer and won at trial, but lost his business because he couldn’t pay the bills in the meantime.

“I paid taxes on that money. I worked for that money,” Stuart told the Washington Post. “Why should I give them my money?”

The brutal efficiency of civil asset forfeiture in this country depends on the universal despair associated with dealing with bureaucracy: When the government takes from people for whom fighting is expensive and time-consuming and unlikely to succeed, at least some of the victims just won’t bother. A decision in Culley that protects people like Lena Sutton won’t make the system of civil asset forfeiture any less unconscionable. But it might prevent civil asset forfeiture from ruining quite as many lives in the process.