In Search of Barbacoa

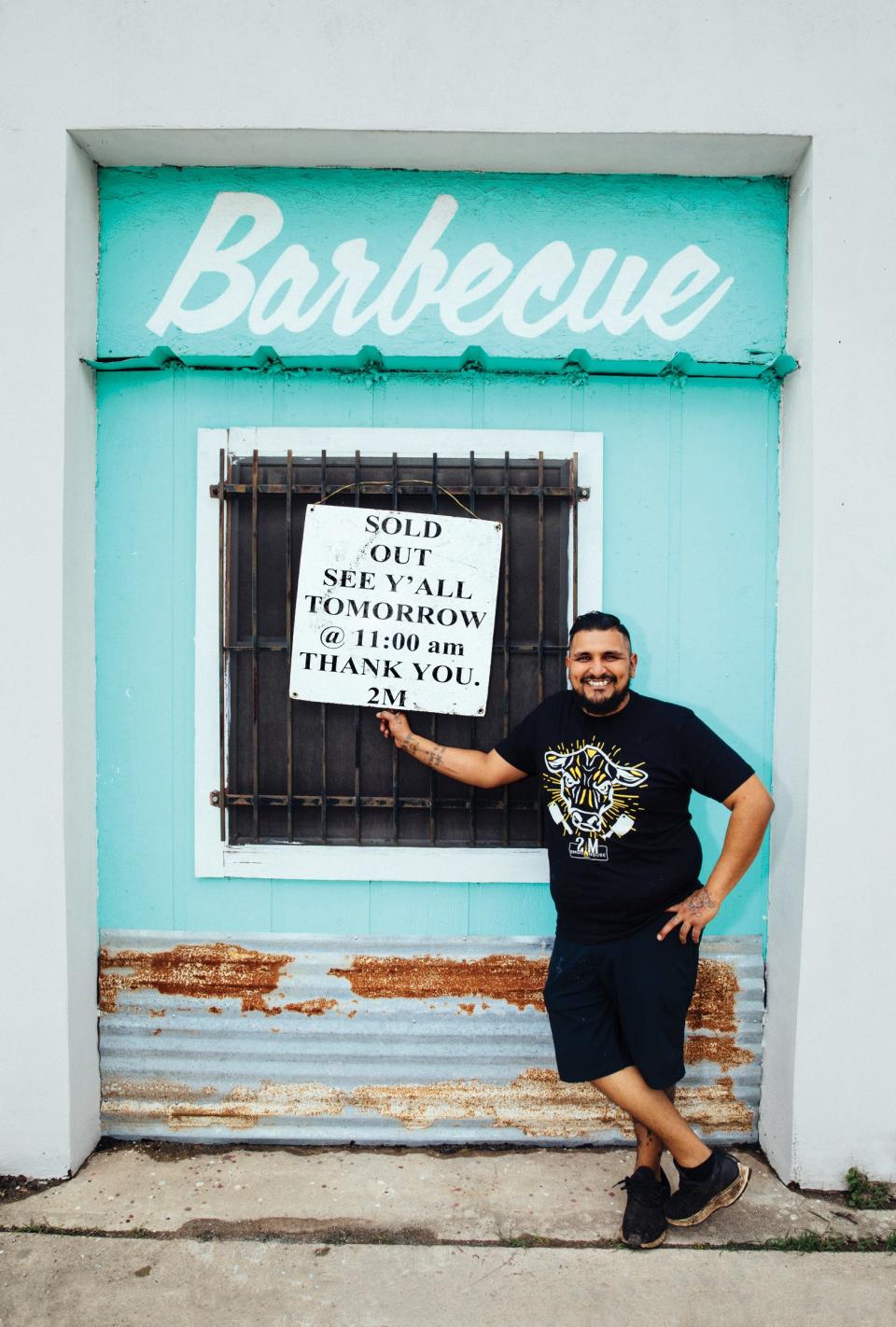

Esaul Ramos is doing prep work for his Sunday barbacoa, as he does every first Saturday of the month. There are 26 hours before the meat will be sold, but still, the time frame is tight. The foundation of this particular barbacoa is beef cheeks, which must be smoked for a couple of hours before they are wrapped in banana leaves, then in aluminum foil, then put in large pots, and finally cooked for 16 hours by the low heat of the smoker. Tomorrow, by 11:30 a.m., it will all be sold out thanks to preorders and of course the dozens of San Antonio locals who form an early line outside 2M Smokehouse, the barbecue joint that pitmaster Ramos and his friend Joe Melig opened in December 2016, in a lot they found on Craigslist (which had previously housed a Mexican restaurant). The barbecue joint that, as one reviewer wrote for the San Antonio Current, has bumped the city “into the will-wait-for-food world for better or for worse.”

But that’s gonna be tomorrow, after you and I have gone well into barbacoa territory.

Barbacoa is a thing of shifting nature. It does not want to be defined. We say the word barbacoa, and we mean many things. I do not come to the pages of Bon Appétit to repeat that it is a method that was brought here from an island in the Caribbean 500 years ago. First, because I am sure you already know that. Second, because it does not even matter: Colonizing sapiens would have arrived at this method by some other route anyway. Also, barbacoa wasn’t brought here. It moved, if you will, for barbacoa’s voice is not passive. Its domains grew, and it has continued to change, to evolve. Barbacoa’s method, a hell-hot underground pit, covered with earth or bricks, sealed like a primordial pressure cooker, now seems as natural to the evolution of human intelligence as the learning of sowing and harvesting.

El Nuevo Cocinero Mexicano en Forma de Diccionario, a handsome dictionary that some in Mexico use for dating and antedating dishes and recipes, was published in 1888. (At least the one I have at home was. I found it at an old bookshop near the zocalo in Mexico City’s center. The owner sold it to me for like $20. Poor bastard never knew what he had on his shelves. Or, my volume is a fake, and I, poor bastard, don’t know what I have on my shelves. This is probably the case.)

El Nuevo Cocinero’s editors sing the praises of barbacoa. “Of all the ways men have invented to cook meats, none can compare to that of barbacoa, for without adding liquids whatsoever, which might make those meats lose part of their substance, and of their flavor; and without them coming in contact with fire, which might rob those meats of their juices; with only the steam coming from the heated earth; and preserving all their nutritious qualities; these meats are so well cooked, so toothsome, as to be exciting to the appetite and easy to digest, even for the weakest of stomachs, all at the same time.” El Nuevo Cocinero then proceeds to list several barbacoas.

There is one barbacoa Mexicana, which is the most basic, therefore the most comprehensive of all. You will recognize it; it almost encompasses the other six. There is a hole, stones, and a big fire built in that hole. The fire will die, and the stones will be quite hot. “You will leave the stones there; and put wet palm leaves over them; then the meat,” which has been prepared with some sort of adobo and wrapped in maguey or other leaves. “You will cover this with earth and enough fire. Eight or ten hours later, the meat will be well cooked.”

In many versions, barbacoa will be accompanied by a consommé. In Central Mexico, where lamb is the most common of barbacoa meats, lamb drippings will fortify the broth, to which garbanzo beans and probably xoconostle (a sweet, acidic cactus prickly pear, sometimes the color of timid rosé wine) will be added. The lamb’s stomach will be stuffed with viscera—liver, heart, kidneys—then tied and put in the pit. (This is called pancita.) It’ll be cooked there like a spicier, less subtle haggis.

Beef head barbacoa is pervasive in cowboy country, up in the northern states of Nuevo León, Sonora, and Chihuahua. Pork barbacoa—in its astonishing guises of cochinita pibil and lechón— may be found in Campeche, Yucatán, Quintana Roo. (I just felt weird for a second, telling you about cochinita as if it weren’t the best pork dish that ever existed, and as if you did not already know this indisputable fact, this fact as factual as the non-flatness of the earth.) Connoisseurs or wannabe connoisseurs (like me) will probably mention barbacoas from Coahuila, made of veal or beef, rubbed with guajillo chile and dried tomato; from Oaxaca, where there are barbacoas, famously lamb, but sometimes beef, larded with almonds and olives; from Veracruz, made out of chicken marinated in ancho and mulato chile; from Chiapas, the barbacoa seasoned with a recaudo made of ancho chile, allspice, thyme, oregano, and vinegar; from Guanajuato, where cascabel chile gives the dish its smoky pungency, and where the pancita may be called montalayo. (There barbacoa will probably be made of goat, and you and I might mistake it for a birria.)

You could travel to all these states of Mexico and try all these regional barbacoa styles. Or you could just go to Los Angeles. Or Philadelphia. Or Austin.

You see, barbacoa cooks live within creative ecosystems. They inherit well-established traditions and techniques. But they are also in the business of reworking earlier barbacoas. There are tweaks, corrections to be made. There is an impulse to make them better, or more personal, or to make them respond to a new set of circumstances (a new city or a new neighborhood, a financial crisis). Barbacoa is neither a recipe nor a formula; it’s a schema: a set of options that can be broadly revised, according to the push or pull of the creative mind.

Barbacoa cooks will take one or several traits of the dish and adapt them to resemble it somehow. In home kitchens—in Mexico and elsewhere— barbacoa will simply be meat wrapped in maguey or banana leaves; it could also be wrapped in maguey “paper” or mixiote. It’s synecdoche at work. No pit? Let’s steam the whole thing in the oven or on the stove. No maguey leaves? Use aluminum foil. Probably the accoutrements will make the barbacoa: salsa borracha (even if it’s not drunk on pulque), pickled onions with manzano chile, cilantro, etc. You will probably think it’s lazy on my part to state it like this, but barbacoa is meat of some kind, wrapped in some leaf or foil or paper, somehow cooked without direct contact with fire, served with some sort of salsa. It has to be served or sold as barbacoa, though. The menu has to list it as “barbacoa,” or the home cook has to ask you something like ¿Vas a querer barbacoa, mijo? (Sorry, purists, but as I said, barbacoa is a thing of shifting nature.)

Barbacoa’s presence in the States has grown rapidly. This of course includes barbacoa at every Chipotle but also the emergence of chef Cristina Martinez’s South Philly Barbacoa, which went from an almost secret spot to appearing on this magazine’s list of the best new restaurants in America in 2016 and on Chef’s Table in 2018. The restaurant now draws lines down the block every weekend. Martinez adapts Central Mexico barbacoa style by using steaming pots for maguey-wrapped lamb. This is just one possibility of the barbacoa premise.

At Asadero Chikali, a taco truck on Atlantic Boulevard in East L.A., you’ll find a northern Mexico barbacoa, a sort of pulled beef steamed in a smoky, loose adobo. The flour tortillas are especially fatty, and the guacamole is also loose. Asadero Chikali is the work of Rosa Pérez and her kids. They’re good. I hope they become millionaires.

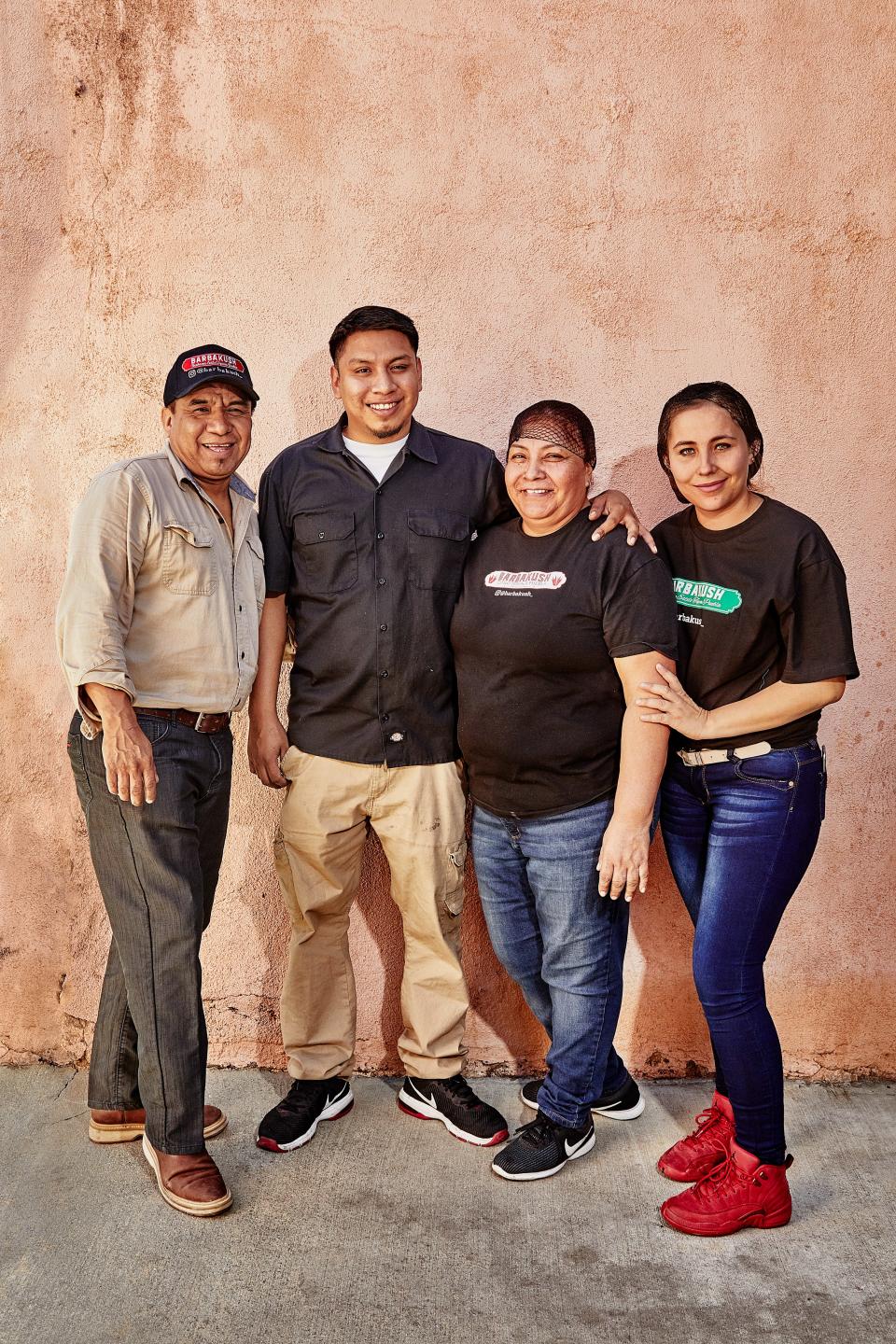

Also in East L.A., in the garage of the Zavaleta/Rodriguez family on Record Avenue, there’s barbacoa with a Poblano (i.e., from the state of Puebla) accent. This is the phenomenon that goes by the name of Barba Kush, where Petra and José Félix cook lambs in a pit excavated in the lot behind a friend’s home. The hole is still visible Sunday morning, newspapers and whatever else just there, semi-burnt, a memorial to all the faithful departed sheep. I take a photo so as not to forget them.

Here’s what’s unforgettable at Barba Kush: the menudo, a Pantone 200-C red stew of lamb tripe and viscera, fiery, springy with the snap of liver and the granulated pattern of the stomach. It’s almost like a second tongue one manages to eat with one’s own tongue. Do this: Use the menudo as a topping for a barbacoa taco, the tortilla just out of the comal at the back of the garage. Second topping: salsa verde. Third topping: pipicha leaves, which impart notes of nasturtium, lime, and cilantro. (By the time you read this, the family will have opened a restaurant at Whittier Boulevard and Mott Street.)

Tacos Quetzalcoatl belongs to the central branch—that is, from Central Mexico—of the barbacoa tree. (In this metaphor, the tree is a large, almost baobab-size maguey.) The pitmaster tells me his name: Quetzaltipocatl Pakal, which is probably made up, but who am I to question? The name seems a portmanteau of quetzal, that magnificent bird; Tezcatlipoca, lord of the skies, nemesis to Quetzalcoatl, the feathered snake; and Pakal, governor of the Maya city-state of Palenque. The guy knows his history, or his mom and dad did.

The small food truck sports the effigy of Quetzalcoatl in a warring posture. The taquero—I’ll call him Q, though I read somewhere his real name is Max—comments on my order like a film critic at some weird personal screening. He says my barbacoa on a flour tortilla is “finger licking good” but only si trais las manos limpias, cabrón (if your hands are clean). He says this in a friendly tone, as if this weren’t the first time we’d met. The meat comes out of a cooler and goes onto the plancha. This is a conservative Central Mexico barbacoa: It is ovine, smelling of fresh wool, and has been cooked in a pit, wrapped in maguey leaves. The lamb has the lovely stink of an athletic animal, which people with more upturned noses than mine would call gamey, and also the anise notes of toasted maguey pencas.

¿Cómo que ya te vas? he says, as he orders me to order another taco. It’s the Omega 2 with spinach, zucchini, mushrooms, bell pepper, string cheese, and some spice dust he prohibits me from inquiring about. Goddamn taco is delicious, though. Before I can say anything, he tells a woman to spike my consommé with a bloodstream of cascabel, morita, and árbol chiles. The soft voice of a 1981 Julio Iglesias singing Hey, no vayas presumiendo por ahí over the speaker keeps me from crying. ¿A poco te picó? Q asks. He’s laughing, of course.

Not more than six years ago, a reviewer could say that Vera’s Backyard Bar-B-Que in Brownsville, Texas, was “the last bastion of South Texas barbacoa.” Today barbacoa is thriving and constantly renewing itself. In the city of Austin we can see this tendency to explore all the possibilities of a premise. Beef iterations at Taqueria Morales, on William Cannon Drive, and at El Primo, on First Street, have the systematic quality of gluing your lips together, characteristic of classic barbacoas. The Austin taco chain Tacodeli, naturally, has jumped on the barbacoa wagon and now serves it Sundays as a breakfast taco. (Is there a better idea than a breakfast taco? I know Bluetooth earbuds exist, and they are a great idea too, but how can you even try to compete with breakfast tacos?)

At Valentina’s Tex Mex BBQ in Austin, pitmaster Miguel Vidal takes beef cheek from the Japanese cattle breed called Akaushi, cooks it low and slow in one of his many smokers, shreds it, and serves it on elongated flour tortillas topped with a tangy, rustic pico de gallo. The beef is deep brown, gelatinous, sticky. Cilantro imparts an herbal freshness to it; onion, a fragrant sharpness. Use lemon and you will have a balancing act of a dish. This taco lives in a twilight zone between street food and haute cuisine, both modes rapidly converging in the dish.

Goat barbacoa at Suerte—a large, sunny space considered one of the city’s best new restaurants— on the other hand, is decidedly haute. Price tag, plating, and portion size indicate that. The tortillas are small and perfectly stretchy. Corn is nixtamalized in-house. The barbacoa has the sweet subtle notes of the banana leaves in which it has been steamed. Chef Fermín Núñez serves it with a grassy tomato-tarragon salsa, a fruity/nutty sesame-habanero salsa, and a refreshing mint sorrel yogurt sauce. It’s like eating at three different barbacoa restaurants at once.

My mind struggles to find an accurate image for barbacoa U.S.A. 2019. There is variety, imagination, personal voices but also market-driven decisions. Barbacoa is like one of those string games where two or more hands create shapes and patterns—cat’s whiskers, a Jacob’s ladder. Barbacoas of all kinds seem to form a Paul Klee–esque artifact, always moving without losing its center.

It is safe to say that many barbacoa affairs are family affairs. Pitmaster Ramos of 2M Smokehouse came to the trade as a sort of child fireman during his family’s weekly barbacoa parties. Mom would make tortillas. “My dad would be out at the pit or the grill, but he’d have maybe too many chelas and the meat would start to burn.” Ramos was young, probably 12, but he’d rescue these meats. And so he would practice, baby steps, himself ruining the occasional meat, until he decided he should become a pitmaster apprentice, then a pitmaster. He wanted to work at La Barbecue in Austin, so he called, went there, and by some curious mix of will, luck, and incipient-but-promising craft, got the job. Then, when he thought he was ready, Ramos and his friend Melig opened 2M, where you can still find traces of Ramos’ grandma’s cooking in the pickled nopales, the serranos, the Oaxaca cheese. (The pork sausage larded with serrano and string cheese was one of my favorite dishes.) His mom used to make the tortillas by hand at 2M, but now the sales volume is just too large for her to handle it.

It is even safer to say that barbacoa is a festive affair. At Valentina’s, barbacoa is served every Sunday; South Philly Barbacoa opens its doors just three days a week: Saturday, Sunday, Monday; Barba Kush is only open Thursday through Monday. In many Mexican towns you’ll find barbacoa at weddings, at quinceañeras, even served on New Year’s Eve. People relate barbacoa to hangovers. “We started making barbacoa every Sunday, but it wasn’t cost effective,” says 2M’s Ramos. “Then we decided to do it only on the first Sunday of the month.” And that made people think of barbacoa as party food even more. Because a good thing that happens once a month will tend toward celebration. Once a month, you can do anything. Calories don’t matter, sugar doesn’t matter, alcohol doesn’t matter. Want another pound? You got it. ¿Otra chela? Be my guest, I don’t even know you, man. Tomorrow’s Monday, and we have every day after that for worrying and for thinking about things that do matter.

Barbacoa commands celebration. But what is this party? What are we celebrating, anyway? Barbacoa cannot be made by one person alone. Barbacoa requires a gathering of sorts. Also, barbacoa celebrates earth, which is its furnace. It celebrates ground. And we all share this ground. This ground, wherever it may be, is yours and mine. Look down. There is no other ground, you know? This is it. This is all we have. Barbacoa, down in its dark, beautiful, meaningful pit, is everybody’s. That should be cause for celebration.

Alonso Ruvalcaba is the author of 24 Horas de Comida en la Ciudad de México. He lives in Mexico City.

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit