Search for the center of L.A. and you might miss the city's heart

A reader wants to know: Where is the geographic center of L.A.?

What, are you trying to torture me?

Even the master mappers of the U.S. Geological Survey, assessing a space as big and blocky as this continental United States (apart from Alaska and Hawaii), found that in spite of the bragging rights claimed by a baby burg in Kansas, “no marked or monumented point has been established by any government agency” as the nation’s geographic center.

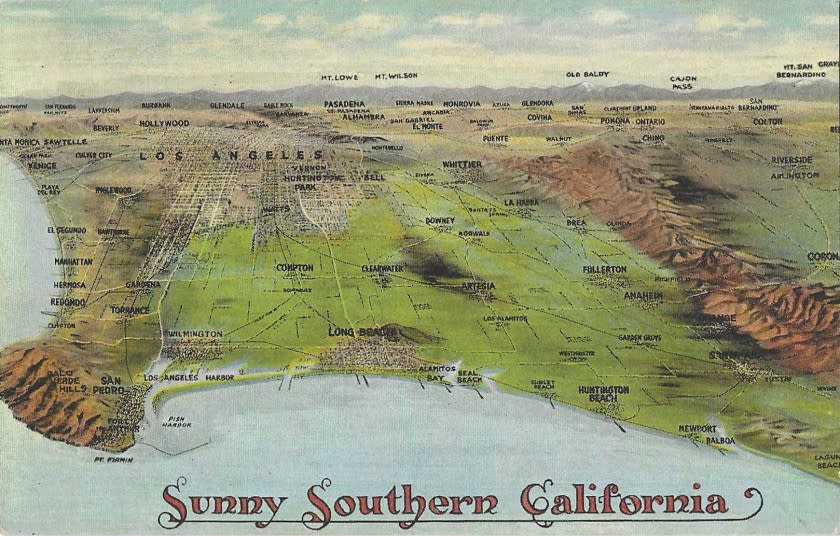

How much harder, then, to fix a “center” in L.A., a city whose silhouette resembles some comic-book alien — a huge, misshapen head and body, and one spindly leg anchored by a single, clumsy foot.

So let’s not speak of the center of L.A., but of its heart.

Downtown? In a hundred years and change, downtown’s civic-power core has had its moments, and right now is another one of them. DTLA’s hip housing and hot restaurant nucleus is the latest of as many death throes and undead revivals as a road-show “Dracula.”

No, L.A.’s real estate landscape has for a long, long time been more like the “Monopoly” game board, a lot of peripheral settlements that sometimes became “downtowns” of their own.

How did the second-most-populous city in the country wind up looking nothing at all like the 19th century’s idea of a “city”?

Accidentally, on purpose.

The earliest Angelenos, the Tongva, wisely built their villages by the water — the L.A. River, the San Gabriel River, the streams and freshets of a hundred hills. The principal village, the Washington, D.C., of the Tongva, was Yaanga, near present-day Olvera Street, marked by a sycamore tree six stories high. So modern L.A. began along the river, not the beach. The Tongva names still on our map — Tujunga, Topanga, Cahuenga — are the heritage of these villages.

The Spanish came, and their religious missions marked their trek along much of the length of California, sites we know as cities: San Diego, San Juan Capistrano, San Gabriel, Ventura, San Luis Obispo, Carmel, San Francisco. Thanks to free “neophyte” forced labor — by Native Americans tied to the missions — the missions became self-sustaining communities.

When the ranchos flourished some years later, on humongous land-grant properties a long way apart, each too became like a little town, with granary, tannery, dairy and gardens. The missions were secularized in the 1830s, and a lot of mission lands that were supposed to be returned to Native Americans wound up — shocking, I know — in the hands of rancheros instead.

So by the time the city of L.A. was founded near present-day Olvera Street in 1781 — half a century before Chicago was created, I’ll have you know — the mission-as-village system was in place, and the ranchos replicated that centrifugal layout of Greater L.A. Eventually, the city began filling itself in between these faraway rancho towns and the original city center.

In 1850, several months before California became a state, L.A. was formally incorporated, and its new Yankee city fathers not only imagined a booming future but would by God make it happen.

And did they want a city and a downtown that looked like Chicago’s or New York’s?

No, sir. These sunshine potentates, more powerful than any rancheros, saw L.A. as a city of destiny, the “white spot” of America (their words), a place free from corruption (not their sort, of course), the visual opposite of the soiled, sweaty cities with their tall tenements and thrusting, packed streets — meaning among other things a place free of undesirable immigrants and the poor.

Paul Gleye is an architecture professor at North Dakota State University. He wrote the 1981 book “The Architecture of Los Angeles,” and he says these kings of L.A. definitely did not want another Manhattan to rise here. “People came to Los Angeles to get away from the ‘dark, walled-in streets’ of Eastern cities,” he told The Times years ago and, more recently, said that, in consequence, “verticality was something to be avoided.”

L.A. was crafted to keep it that way. Los Angeles, decreed a 1910 planning committee report, would develop “along broad and harmonious lines of beauty and symmetry” — broad, not tall.

And here’s some major myth-busting for you: The long, long absence of tall buildings was an aesthetic decision, not a seismic one. A whole year before the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, L.A. capped building heights at 130 feet. Voters raised that to 150 feet in 1910, and there it stayed until 1957, when the sky was the limit. (Anyway, The Times decreed breezily, earthquake perils were “largely illusory.”)

The city’s first skyscraper, constructed in 1904, is the 120-foot-tall Continental Building on Spring Street downtown. It’s now a place of lofts. Its architect was the senior in the father-son firm of Parkinson and Parkinson, which designed some of L.A.’s defining buildings: Bullocks Wilshire, Union Station and the Coliseum.

And the standout, City Hall. For 30 years after it was built, in 1927, it had the skyline virtually to itself. It was the Daily Planet building in the TV “Superman” show. It is there on every badge on every LAPD uniform — a paradox when you think about it, given the epic battles between police and City Hall over the years.

The notion of downtown as the heart of L.A. was getting pulled apart, thread by thread. “For a while,” says Ron Davidson, who’s a professor of geography and environmental studies at Cal State Northridge, “the problem was that downtown was too busy — too many cars, too many people, so crowded and congested. That was what was wrong with it.” As he told me that, I laughed, thinking of downtown and the variously attributed remark about the popular restaurant where “nobody goes there any more — it’s too crowded.”

Instead, people’s new automobiles took them to shops and jobs closer to home: the Valley, the Westside, the South Bay. “The centerlessness is the theme here.” By the time the Summer Olympics opened here in 1932, Davidson said, “sprawling” was the adjective inevitably paired with “Los Angeles.”

What was left of downtown’s shopping charm was siphoned away beginning in the 1950s by the regional shopping mall — a creation of Victor Gruen, an Austrian architect who moved here in 1941.

Not until the 1970s and ‘80s did downtown high-rises rise again in earnest. The huge downtown and Bunker Hill redevelopment project altered the skyline with buildings that were glittering but not welcoming — a 9-to-5 workday hive, a dead zone nights and weekends.

Now, the center is holding once more. Younger Angelenos especially want an urban and urbane life, and they’re finding it not just in the pleasures of new museums and music, but in glorious 1920s and ‘30s downtown buildings that were spared the wrecking ball, mostly because the expanding L.A. didn’t need to tear down in order to build up.

As for that tiresome insult that Los Angeles is six or 16 or 88 suburbs in search of a city — yeah, so what? It was spun off, so Davidson thinks, from the title of Luigi Pirandello’s 1921 play, “Six Characters in Search of an Author.”

The first to tweak seems to have been Aldous Huxley, the visionary author and spiritual philosopher. In his 1925 book “Americana,” he calls us “nineteen suburbs in search of a city.” (By World War II, Huxley was an Angeleno himself. He lived in a house below the Hollywood sign, and died the day JFK was assassinated, his spirit unchained by a deathbed dose of a then-legal psychedelic drug called LSD.]

And now it’s L.A., not New York, that other places the world over look to for a prototype. As Davidson says: “For much of its history, L.A. was the fluke nobody cared about. Now it’s the post-modern city, and that’s the trend globally.”

Revenge is sweet, even if it takes an hour to drive there.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.