Searching for my identity as a mixed-Black woman adopted by a white family

When all you have are pieces of your story, do you have a story at all? And if you don’t have a story, what do you have? And how does it affect who you are internally, and out in the world?

In a culture that deeply values personal and family histories that appear to be seamless — at least on the surface — those of us who have little or nothing to go on can feel alienated and alone. Which is why so many adoptees search.

For me, it was easier than it was for the majority of my adoptee friends, many of whom were adopted internationally from Korea in the 1970s and ’80s. Plenty of their birth documents were forged, “misplaced,” or even destroyed by their adoption agencies and the middlemen and women who facilitated them. And then they have the added barrier of learning a whole other language and navigating an entirely new culture, institutions and bureaucracy in order to find even basic details about the circumstances of their birth and relinquishment or any information about living biological relatives. As a domestic, mixed-Black transracial adoptee, my search for my birth family and my beginnings was far easier to navigate, although I didn’t know it at the time I began searching.

Growing up, I had sometimes asked my adoptive parents for various details about my background. Invariably, my mother pulled out a small file folder and extracted from it a page-long document entitled, “Non-Identifying Information.” This is a document that agencies are allowed to give to adoptees and adoptive families providing information about birth parents while keeping them anonymous.

You were born 1/30/75 at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan. At birth you weighed 5 lbs. and 15 oz. and you were 19” in length. You arrived at 6:12 a.m. and you had black hair, blue eyes, and average build. You were described as very alert and responsive. There were no known abnormalities or birth injuries noted. You were placed in a foster home until you joined your adoptive family on 6/10/75.

So began my sheet of “Non-Identifying Information,” which went on to list various facts about my white Irish-American birth mother and her family members. It contained almost no information about my Black birth father or his relatives. I remember staring at this sheet of paper on many occasions as a child, some of it making sense and finding a place in my consciousness, some of it disappearing from my mind as quickly as it entered. There was another piece of paper in the file, which I don’t think I was supposed to see. It listed my adoption fee as $500. I was designated a “special needs” child, since I was Black. I couldn’t really make sense of this until I was in my 20s and learned about racial capitalism and supply and demand in adoption (that is, healthy white babies are the most in demand and will fetch the highest price in a society that values and invests in healthy white people the most).

When I was 19, I decided I wanted to see if I had any biological siblings. So, I contacted my adoption agency and asked for any “identifying information” they had on file (information that could reveal the identity of one or both of my birth parents). Agency staff wrote that they had been in communication with my birth mother, who had given them permission to share her identity with me, should I ever reach out to them and ask for it. Thus began a long, complicated, on-again and off-again relationship with my birth mother, which ended with her death from a rare cancer in 2014. While initially getting to know her, she told me that she had had a very brief relationship with my birth father and couldn’t give me any real information about him beyond his name. She also warned me that he was “dangerous,” that she didn’t trust him, and that they “were both lost souls” at the time they got together. And, as it turned out, I did not have any biological siblings.

I started seeing a therapist who specializes in adoption issues around this time, and she was able to track down material on my birth father. She discovered he had died from injuries he had sustained from a high speed police chase in Palo Alto, California, in 1981, when I was 6. This revelation was hard for me to process, since it was a loss, but one that felt simultaneously distant and immediate. In addition, I couldn’t help but note that I had not only lost my birth father, but all of his stories and all of the stories from that side of the family — which was Black, like me. In fact, he and they were the only parts of my lineage that could have understood and held the blackness that set me a country apart from both my white adoptive and biological families. This was a kind of racial and cultural damage I hadn’t anticipated.

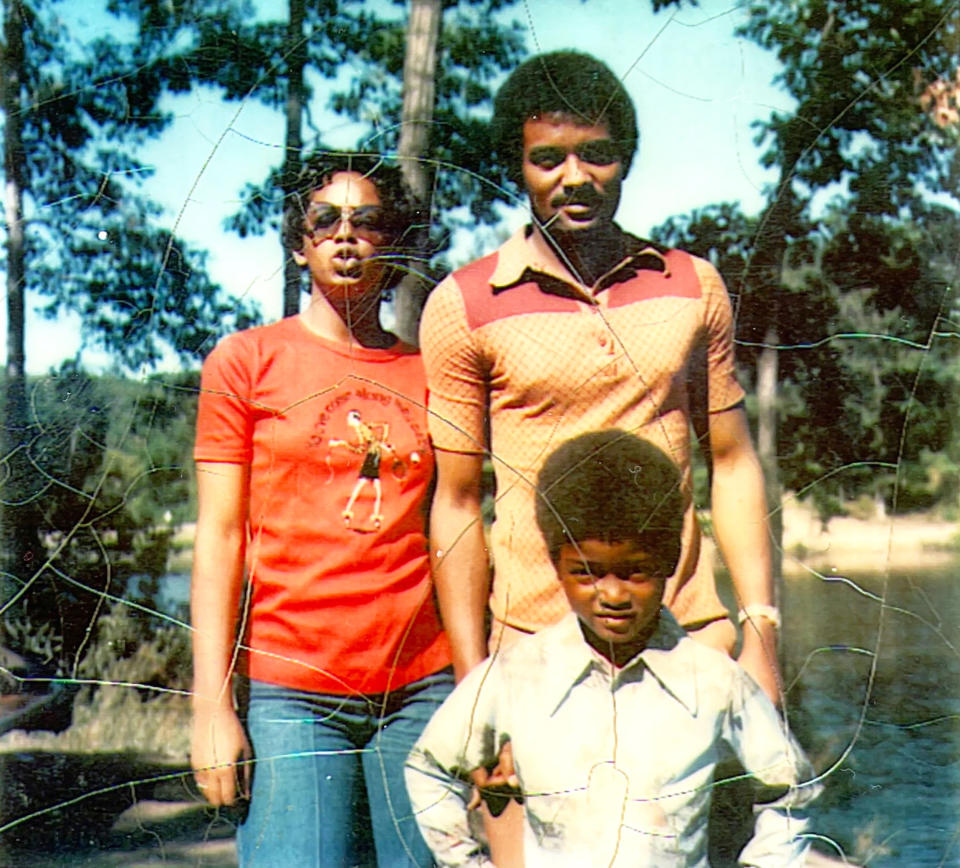

I eventually tracked down my paternal grandfather, and was even able to talk to him some years before his death. Likewise, conversations and meetings with my biological aunt and uncle on my father’s side have filled in many gaps in my story, and have given me the great gift of a fuller picture of my father. I may have never met him, but I can surmise so many things about him from the little information I do have.

Adoptees will never have fully fleshed out stories of our origins, but we do have the conviction that we deserve far more truths than we ever receive, and we have a dogged determination to seek them out. All of this can make us feel frustrated and even angry, but by talking to other adoptees we realize that we are actually not alone in our struggles, and that there are strategies and communities we can build to help mitigate the difficulty and disappointment. We also have imaginations that we can use to explore the people and possibilities that brought us into existence and with whom we co-create our identities.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com